Eight

readers covered everything from passionate poems of love (only three

days for Valentine's) to simple poems of innocent childhood, and

poems of the inspirational type. Exceptional feminist poets like

Adrienne Rich were part of the mix.

Sunil, Priya, Pamela, Sheila, Gopa, KumKum, Talitha

Angelou

has become the most popular poet, no wonder with so many women in the

group. Neruda also. Most were modern or contemporary poets, except

for Shakespeare and Nashe.

KumKum, Talitha, Preeti, Sunil, Priya

There

is not only variety in the poetry, but an even greater variety in the

kinds of things these poets did, from writing plays and political

pamphlets to dancing and diplomacy.

Priya, Pamela, Sheila, Gopa, KumKum, Talitha, Preeti

We

have not run out of new poets to explore, such as Marge Piercy and Anne

Sexton. Here we are, happy as could be, at the end of another

reading:

Sheila, Preeti, Gopa, Priya, KumKum, Talitha, Pamela, Sunil, Joe

Present: Pamela, Preeti, Joe, Talitha, KumKum, Gopa, Sunil, Priya

Absent: Ankush (train arrived 4 hours late), Govind (off to Delhi), Mathew (he was on tour, to Hyderabad), Sreelatha (cancelled last minute for family obligation), Zakia (out of town), Kavita (did not respond), Thommo (did not respond)

The next reading for the novel Light in August by William Faulkner has been fixed already for Fri Mar 27, 2015. Sunil requested if possible for the reading sessions to be on a fixed Friday of the month. So far we have been polling readers at each session to establish the best date for the next month, preferably on a Friday, excepting the third (Sunil & CJ have a séance on that day).

1. Pamela

Maya Angelou (1928 – 2014)

The following excerpt is taken from her biography on the Poetry Foundation's website:

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/maya-angelou

“Maya Angelou was an acclaimed American poet, storyteller, activist, and autobiographer. Her career spanned that of -a singer, dancer, actress, composer, and Hollywood's first female black director, but is most famous as a writer, editor, essayist, playwright, and poet. As a civil rights activist, Angelou worked for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. In 2000, Angelou was awarded the National Medal of Arts by President Bill Clinton. In 2010, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honour in the U.S., by President Barack Obama.

Angelou’s most famous work, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969), deals with her early years in Long Beach, St. Louis and Stamps, Arkansas, where she lived with her brother and paternal grandmother. She was first cuddled then raped by her mother's boyfriend when she was just seven years old.

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings is the first of Angelou’s six autobiographies. It is widely taught in schools, though it has faced controversy over its portrayal of race, sexual abuse and violence.

It took Angelou 15 years to write the final volume of her autobiography, A Song Flung up to Heaven (2002).

Angelou was also a prolific and widely-read poet, and her poetry has often been lauded more for its depictions of black beauty, the strength of women, and the human spirit; criticizing the Vietnam War; demanding social justice for all—than for its poetic virtue. basic survival."

She was the first black woman to have a screenplay (Georgia, Georgia) produced in 1972. She was honoured with a nomination for an Emmy award for her performance in Roots in 1977. In 1979, Angelou helped adapt her book, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, for a television movie of the same name.

One source of Angelou's fame in the early 1990s was President Bill Clinton's invitation to write and read the first inaugural poem. Americans all across the country watched as she read On the Pulse of Morning, which begins A Rock, a River, a Tree and calls for peace, racial and religious harmony, and social justice for people of different origins, incomes, genders, and sexual orientations.

Angelou’s poetry often benefits from her performance of it: Angelou recites her poems before spellbound crowds. Indeed, Angelou’s poetry can also be traced to African-American oral traditions like slave and work songs, especially in her use of personal narrative and emphasis on individual responses to hardship, oppression and loss.”

Pam liked the last two lines of Touched by an Angel:

Yet it is only love

which sets us free.

Joe observed there are two characteristics of love emphasised in the poem: its ability to strike the chains of fear from a person, and its ability to set the person free. Customarily, it is truth that is claimed to set us free, as in John 8:32, in the words of Jesus

you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free

Indeed, love can often enslave one to an earthly lover. Sheila said if you substitute the word God for love (since God is love), then the two claims are comprehensible. But Priya asked if God is substituted, the poem becomes limited in the scope of its appeal to theists. Should the poem not make just as much sense to atheists, she asked? Sunil chimed in by adding that surely atheists are capable of love. And why should humans associate love only with God? Gopa 'totally agreed' with Angelou, she said.

2. Sheila Cherian

Iris Hesselden

Sheila Cherian read an inspirational poem is as the last two lines state, to have fortitude in the face of life's troubles:

Be strong and be cheerful in all of life's storms,

And learn how to dance in the rain!

Who is the author, Joe asked; Sheila did not know. She got this poem by copying from a Scottish magazine. KumKuum said Joe used to go merrily dancing in the rain with the children when the monsoon burst over Delhi, sending up the scent of dry earth wetted by the torrent of rain. There was universal acclaim for the poem when Sheila finished reading it. KumKum called it 'sweet and simple' and Priya said it was 'encouraging, hopeful.' Sheila said it was a good poem to read when one is depressed or discouraged by circumstances, for it urges the reader to

Go forward with courage and follow your star,

And leave past misfortunes behind.

3. Gopa & KumKum (duet)

Rabindranath Tagore

KumKum and Gopa read alternate sections of a long poem by Rabindranath, Devoured by the Gods. KumKum gave the gist of the poem by way of introduction. She commented in passing that Bongis eat food with their fingers, but without staining the palm of their hand with the food, and contrasted it with what she considered the uncivilised way in which Malayalees (her husband, for instance) would pitch into pootu and payam or some other dish with gusto, massaging the food with the entire hand; she made an imitative hand gesture saying 'kuchoo, kuchoo.' She went to the extent of noting that when Keralites went outside Kerala they acquired more civilised manners at table. Talitha drew the conclusion then we must all be benighted folk living here in Kerala!

When the poem was finished Joe thought it could be better enacted on the stage, since it is a dramatic poem with several voices. KumKum said William Radice, the translator, turned it into an opera in English and staged it. It seems Rabindranath wrote many poems as little dramas to be produced on stage.

Pamela addressed Talitha to ask if it were not like Jonah's story in the Bible. Talitha answered, no, because he was going some place else. Priya then compared it to the poem Lord Ullin's Daughter where a chieftain makes off with the daughter of the Lord, with the Lord's men in chase:

A chieftain, to the Highlands bound,

Cries, ``Boatman, do not tarry!

And I'll give thee a silver pound

To row us o'er the ferry!''--

It all ends in grief as the storm overtakes them and the Lord discovers his child drowned in the storm:

One lovely hand she stretch'd for aid,

And one was round her lover.

KumKum said Rabindranath wrote this poem to counter the superstitious beliefs that surrounded the lives of ordinary folk, and they are willing to appease a storm god by sacrificing a person. Gopa too agreed that many of his poems were about the absurdity of blind faith. KumKum said Rabindranath was a Brahmo in belief and tried to open people’s eyes to the curse of a life lived in superstition.

Talitha, however, read the poem as being too understated to convey a strong condemnation of such childish beliefs; he seems to sympathise with the human sacrifice. Rabindranath was against many patriarchal customs among Hindus of the time, e.g., forbidding widows from remarrying, considering widows such bad luck that they have to be kept out of sight at festivals. Gopa said in Bengal suttee was common. Priya mentioned the export of widows to Benares. Gopa said if you are a Vaishnavite in Bengal, then a widow is encouraged to spend her time in Mathura-Brindavan as the sites of Lord Krishna. Sunil and others think the practice is more like abandonment, rather than widows voluntarily going away to lead a life of renunciation.

Talitha wished the poem were read in Bengali and they could follow with some knowledge of Sanskrit what was going on. I do not think Bengali is so easily comprehended, particularly the poetic Bengali of Rabindranath.

4. Talitha

Marge Piercy

You can read an extensive biographical note at Poetry Foundation:

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/marge-piercy

She has published 17 volumes of poetry and written as many novels. She was born in Detroit of Lithuanian Jewish descent. “Piercy’s poetry is known for its highly personal, often angry and very emotional timbre. She writes a swift free verse that shows the same commitment to the social and environmental issues that fill her novels.” Her love of books originated from a the time she suffered a bout of rheumatic fever in childhood. Her mother read voraciously and encouraged her daughter to do the same.

Her work shows commitment to the dream of social change (what she might call, in Judaic terms, tikkun olam, or the repair of the world), rooted in story, the wheel of the Jewish year, and a range of landscapes and settings. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marge_Piercy )

She has been married three times and now lives in Cape Cod. The first poem, A work of artifice, talks of the oppression of women:

one must begin very early

to dwarf their growth:

the bound feet,

the crippled brain,

the hair in curlers,

the hands you

love to touch.

Joe told of his horror at seeing the trees in front of the Emperor's Palace in Central Tokyo, the branches being twisted and curled and bound in strong wires, in order to make the trees grow in an arbitrary human-imposed fashion. Talitha spoke of a creative exercise to read Ibsen's The Doll's House, and then giving this poem to get the reactions of students. The similarities came out in excellent ways, she said.

The second poem, To be of use, extols work and the ideal of being immersed in work. Gopa wondered if this was a Calvinist attitude to work. Talitha referred to the different images of work – jumping into work head first, persisting in hard work and toiling in the mud to move things forward a little. There is even beauty in it:

.. the thing worth doing well done

has a shape that satisfies, clean and evident.

5. Preeti

Adrienne Rich

Powell, a fellow poet, recounted how Rich in a poem titled What Kind of Times Are These, dwelled on a patch of grass in the space between two stands of trees as she mulled a sense of collective fear in 2002, leading up to the US-led invasion of Iraq.

"She's thinking about how people disappear, and how we're living in a country that's so full of dread," Powell said. "But she's not talking about war. She's talking about it in the language of houses and shadows and leaf mould." (D.A. Powell, see

http://uk.reuters.com/article/2012/03/29/uk-rich-obit-idUKBRE82S04420120329

For a review of her life when she died in 2012 see the article titled Adrienne Rich, feminist poet who wrote of politics and lesbian identity, dies at 82:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/books/adrienne-rich-feminist-poet-who-wrote-of-politics-and-lesbian-identity-dies-at-82/2012/03/28/gIQAQygghS_story.html

Adrienne Rich was a feminist poet and critic. She worked in the Civil Rights movement and got a young poets award. She deals in archetypal female figures. The Poetry Foundation bio of hers is perceptive and does justice to her varied activities and political stances:

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/adrienne-rich

Preeti quoted the poet's conception of what a poem is: (need a quotation from Preeti)

Adrienne Rich also uses the powerful imagery of the atom bomb. Joe commented about the poem What Kind of Times Are These, that the word disappear occurs three times, forming a motif. The poem was written in 2002, well after 9-11 and the looming Iraq War which is the backdrop.

One senses the anticipation of the illegal renditions and so on which made America look like a new Soviet Union; people are sent to black holes like Guantanamo, and then no habeas corpus can save them from inhuman treatment and torture, administered in secrecy.

Joe referred to an excellent book authored by Mohamedou Ould Slahi - writer of the Guantanamo Diary, detained without charge and without trial for a decade and more:

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/15/books/review/guantanamo-diary-by-mohamedou-ould-slahi.html

Guantanamo Diary reads like Kafka's The Trial. Mr. Slahi emerges from the pages of his diary, handwritten in 2005, as a curious and generous personality, observant, witty and devout, but by no means fanatical. More about him and his editor, Larry Siems, are at

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jan/29/guantanamo-diary-detainee-new-york-times-bestselling-author

Excerpts read by famous authors are here below; please listen to Stephen Fry and Peter Serafinowicz:

http://guantanamodiary.com

Talitha commented on the deliberate vagueness of the second poem, Dreamwood. Preeti said as children we see patterns in moss, shadows, etc. Sunil agreed that daydreaming in class was constant. There is a typing stand, a woman typing a report and seeing patterns

… she would recognize that poetry

isn’t revolution but a way of knowing

why it must come.

6. Joe

Pablo Neruda

Pablo Neruda was a Chilean poet who was born to a working-class family in 1904 in a small town in S Chile. His mother died when he was young. When he showed early interest in poesy his father was exasperated enough to forbid him to write in the family name; so he adopted the name by which he is known and it became his legal name.

He moved to the capital city of Santiago and published his first collection, Book of Twilight, in 1923. Indeed Neruda brought his work to the principal of the local girls' school, the famed poet Gabriela Mistral (she won the Nobel for Lit in 1945), who told him: "I was sick, but I began to read your poems and I've gotten better, because I am sure that here there is indeed a true poet."

He followed it a year later with a thin collection called Veinte Poemas de Amor (Twenty Poems of Love), to which he added a longer poem called Una Canción Desesperada (A song of despair). This collection instantly catapulted him to fame. It is the first poetry in Spanish that unabashedly celebrates erotic love in sensuous, earthly terms. "Love poems were breaking out all over my body," he later recalled.

His example shows like that of many other poets the importance of giving voice to one's literary talent as early as possible. What you could write then, may lack maturity, but the feelings and experiences of that spring time of one’s existence can never be recaptured in maturity. They will have an abandon, a freshness, a boldness, and an originality of voice which will be at the height of their strength. How strong you can imagine from the fact this collection has sold over two million copies and has been translated into all major languages, and in English itself there must be a dozen writers and poets who have attempted to translate them. K Satchidananadan and Balachandran Chullikkad have translated some poems of his into Malayalam. Marquez considered Neruda the great voice of poetry from S America, calling Neruda "the greatest poet of the 20th century in any language.” This is not to forget all the other great voices like Gabriela Mistral, Ruben Dario, Octavio Paz, Jorge Luis Borges, Cesar Vallejo, Juana Inés de la Cruz , and so on.

He had a colourful life: ambassador of Chile in several countries, visits to Europe, membership in the Communist Party, an ardent supporter of the Republican cause in Spain during the time the fascists under Gen Franco were making the country into a a dictatorship with help from the Nazis. He worked for the election of Salvador Allende in Chile, a socialist, and when Gen Pinochet overthrew the elected government with US help, he was bitterly disappointed, and withdrew to a corner of Chile and died soon after in 1973. You can read the wiki to get an extensive biography. His complete works are in three volumes, 3,522 pages long.

I know Neruda has been recited three times before, but why Veinte Poemas never figured I can’t tell. I will make good that deficit by reading a couple of poems from the collection. They are erotic, there’s no doubt, and when he was asked, he admitted to two girls being responsible for the evocation in the poems, Marisol and Marisombra. The world has to thank them. The translations are mine. I have used the translation of W. S. Merwin (Penguin, 1969) as a crib. It’s available on the Web. I have taken considerable liberties with the Spanish text to make the heavily symbolic and sometimes veiled references to sex more explicit. I hope I have made them less dense in the process. Please excuse the sacrilege.

Talitha commented on 'rough peasant's body,' a self-description of the poet. Neruda probably had a soft body, she opined! Priya said the poet stands out as a lover. KumKum who distrusts erotic love, said a woman is foolish to be loved by someone like Neruda. The point is we do not know how much is fiction and how much is derived from reality in any poem, even if the poem uses the personal pronoun. Sunil liked the line:

Love’s so brief, forgetting so prolonged.

Joe was teased for his choice of this kind of passionate poem, or the second one which is a poem of longing for what is past. But how many poets can boast of a slight book that is still in print a century later, and has sold two million copies?

7. Sunil

Anne Sexton

Sunil said Anne Sexton was a manic-depressive and poetry was recommended by her therapist as form of healing. One day after readying her latest volume for the press, she went to the garage, turned on the car's engine, and died by carbon monoxide poisoning. She is buried in Forest Hills cemetery in Ballston, MA. You can read a good bio of hers at

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/anne-sexton

In the poem 45 Mercey Street she is looking for comfort from the past, recalling her family home. Sunil said it is a simple and innocent part of her life. KumKum liked the poem Young and Priya said it was a good one:

A thousand doors ago

when I was a lonely kid

in a big house with four

garages and it was summer

as long as I could remember,

I lay on the lawn at night,

clover wrinkling over me,

the wise stars bedding over me,

7. Priya

Poems of Spring by Shakespeare, Hopkins, Elfriede Jelinek, Thomas Nashe, Amy Gerstler

Priya was taken by the fact that the season of basant is round the corner and chose various poems from Middle English times to the present, celebrating spring. Shakespeare in his pastoral mood is simple and nostalgic, but the call of the cuckoo reminds him of cuckolded husbands. Hopkins is always a bit on the religious side:

What is all this juice and all this joy?

A strain of the earth’s sweet being in the beginning

In Eden garden.

Before the spring is lost let's taste it, he says.

Elfriede Jelinek lost her family in the Holocaust. She was a member of the Communist Party and took up writing as a therapy. There was a movement of protest against her getting the Nobel for Literature in 2004. Her poem is opaque; perhaps the trouble is with the translation, thought Talitha.

Amy Gerstler's poem, In Perpetual Spring, was read to great acclaim! Sunil liked the lines:

in search of medieval

plants whose leaves,

when they drop off

turn into birds

Everyone liked the ending:

your faith that for every hurt

there is a leaf to cure it.

It was a very appealing poem.

1. Pamela

Maya Angelou (1928 – 2014)

1. Touched by an Angel

We, unaccustomed to courage

exiles from delight

live coiled in shells of loneliness

until love leaves its high holy temple

and comes into our sight

to liberate us into life.

Love arrives

and in its train come ecstasies

old memories of pleasure

ancient histories of pain.

Yet if we are bold,

love strikes away the chains of fear

from our souls.

We are weaned from our timidity

In the flush of love's light

we dare be brave

And suddenly we see

that love costs all we are

and will ever be.

Yet it is only love

which sets us free.

2. Caged Bird

A free bird leaps

on the back of the wind

and floats downstream

till the current ends

and dips his wing

in the orange sun rays

and dares to claim the sky.

But a bird that stalks

down his narrow cage

can seldom see through

his bars of rage

his wings are clipped and

his feet are tied

so he opens his throat to sing.

The caged bird sings

with a fearful trill

of things unknown

but longed for still

and his tune is heard

on the distant hill

for the caged bird

sings of freedom.

The free bird thinks of another breeze

and the trade winds soft through the sighing trees

and the fat worms waiting on a dawn bright lawn

and he names the sky his own

But a caged bird stands on the grave of dreams

his shadow shouts on a nightmare scream

his wings are clipped and his feet are tied

so he opens his throat to sing.

The caged bird sings

with a fearful trill

of things unknown

but longed for still

and his tune is heard

on the distant hill

for the caged bird

sings of freedom.

2. Sheila Cherian

Iris Hesselden

Dance in the Rain

Life isn't just waiting for storm clouds to pass,

It's learning to dance in the rain,

It's looking for rainbows and seeking for joy

And knowing that love will remain.

This life has its problems, its worries and woes,

And each of us must take our share,

But look to the seasons and all they can give,

There's beauty around everywhere.

And seek for the wonder, the laughter and love,

The friendship to warm heart and mind,

Go forward with courage and follow your star,

And leave past misfortunes behind.

Hold fast to your hopes and keep them all safe,

Your daydreams are never in vain;

Be strong and be cheerful in all of life's storms,

And learn how to dance in the rain!

3. Gopa & KumKum (duet)

Rabindranath Tagore (1861 – 1941)

DEBOTAAR GRASH: Devoured by the Gods

The news has gradually spread around the villages –

The Brahmin Maitra is going on a pilgrimage

To the mouth of the ganges to bathe. A party

Of travelling companions has assembled – old

And young, men and women; his two

Boats are ready at the landing stage.

Moksada too is eager for merit –

She pleads, ‘Dear grandfather, let me come with you.’

Her plaintive young widow’s eye cannot see reason;

She entreats him, she is hard to resist. ‘There is no

More room,’ says Maitra. ‘I implore you at your feet.’

She replies, weeping – ‘I can find space

For myself somewhere in a corner.’ The Brahmin’s

Mind softens, but he still hesitates

And asks, ‘But what of your little boy?’

‘Rakhal?’ says Mokshada, ‘he can stay

With his aunt. After he was born I was ill

For a long time with puerperal fever, they despaired

Of my life; Annada took my baby

And suckled him along with her own – she gave him

Such love that ever since then, the boy

Has preferred his aunt’s lap to mine. He is so

Naughty, he listens to no one – if you try

And tell him off, his aunt comes

And draws him to her breast and weeps and cuddles him.

He will be happier with her than with me.’

Maitra gives in. Moksada immediately

Hurries to get ready – packs her things,

Pays respect to her elders, floods

Her friends with tearful goodbyes. She returns

To the landing-stage – but whom does she see there?

Rakhal, sitting calmly and happily

On board the boat – he has run there ahead of her.

‘What are you doing here?’ She cries. He answers,

‘I’m going to the sea.’ ‘You are going to the sea?’

Says his mother, ‘You naughty, naughty boy,

Come down at once.’ His look is determined,

He says again, ‘I’m going to the sea.’

She grabs his arm, but the more she pulls

The more he clings to the boat. In the end

Maitra smiles and says tenderly, ‘Let him be,

He can come along.’ His mother flares up-

‘All right, then, come,’ she snaps,

‘The sea can have you!’ The moment these words

Reach her own ears, her heart cries out,

Repentance runs through it like an arrow; she clenches

Her eyes and murmurs, ‘God, God’;

She takes her son in her arms, covers him

With loving caresses, blesses him, prays for him.

Maitra draws her aside and whispers,

‘For shame, you must never say such things.’

Suddenly Annada rushes up – people

Have told her that Rakhak has been allowed

To go with the boats. ‘My darling,’ she cries,

‘Where are you going?’ ‘I’m going to the sea,’

Says Rakhal cheerfully, ‘but I will come back again,

Aunt Annada.’ Nearly mad, she shouts at Maitra,

‘But who will control him, he is such a mischievous

Boy, my Rakhal! From the day he was born

He has never been away from his aunt for long-

Where are you taking him? Give him back!’

‘Aunt Annada,’ says Rakhal, I’m going to the sea,

But I’ll come back again.’ The Brahmin says kindly,

Soothingly, ‘So long as Rakhal is with me

You need not fear for him, Annada. It is winter,

The rivers are calm, there are many other

Pilgrims going – there is no danger

At all. The trip will take two months –

I shall bring your Rakhal back to you.’

At the auspicious time and with prayers

To Durga, the boats set sail. Tearful

Womenfolk stay behind on the shore.

The village by the Churni river seems tearful

Too, with its wintry morning dew.

*

The pilgrimage is over and the pilgrims are returning.

Maitra’s boat is moored to the bank,

Waiting for the afternoon tide. Rakhal,

Curiosity satisfied, whimpers with homesick

Longing for his aunt’s lap. His heart

Is weary of endless expanses of water.

Sleek and glossy, dark and curving

And cruel and mean and spiteful water,

How likw a thousand-headed snake it seems,

So full of deceit, greedy tongues darting,

Hoods readring, mouths foaming as it hisses and roars

And eternally lusts for the children of earth!

O earth, how speechlessly loving you are,

How stable, how certain, how ancient; how smilingly,

Greenly, softly tolerant of all

Upheavals; wherever we are, your invisible

Arms embrace us all, day and night,

Drae us with such huge and rapturous force

Towards your calm, horizon-touching breast!

Every few moments the restless little boy

Comes up to the Brahmin and asks anxiously,

‘Grandfather, when will the tide come?’

Suddenly the still waters stir,

Awaking both banks with hope of departure.

The prow of the boat swings round, the cables

Creak as the current pulls; gurgling,

Singing , the sea enters the river

Like a victory-chariot – the tide has come.

The boatman says his prayers and unleashes

The boat on to the northward-racing stream.

Rakhal comes up to the Brahman and asks,

‘How many days will it take us to get home?’

With four miles gone and the sun still not set

The wind has started to blow more strongly

From the north. At the mouth of the Rupnarayan river,

Where a sandbank narrows the channel, a fierce

Seething battle breaks out between the scurrying

Tide and the north wind. ‘Get the boat to the shore.’

Cry the passengers repeatedly – but where is the shore?

Everywhere whipped up water claps

With a thousand hands, its own mad death- dance:

It jeers at the sky in the furious uprush

Of its foam. On one side are glimpses of the distant

Blue line of the woods on the bank; on the other,

Ravenous, gluttonous, murderous waters

Swell in insolent rebellion against the calm

Setting sun. The rudder is useless

As the boat spins and tumbles like a drunkard.

The men and women aboard tremble

And flounder as icy terror mixes

With the piercing winter wind. Some are dumb

With fear; others yell and wail and weep

For their dear ones. Maitra ashen- faced,

Shuts his eyes and mutters prayers.

Rakhal hides his face in his mother’s breast

And shivers mutely. Desperate now

The boatman calls out to everyone, ‘Someone

Amongst you has cheated the Gods, has not

Given what is owing- hence these waves,

This unseasonal typhoon. I tell you, make good

Your promise now – you must not play games

With angry Gods.’ The passengers throw money,

Clothes, everything they have into the water,

Racking nothing. But the water surges higher,

Starts to gush into the boat. The boatman

Shouts again. ‘I warn you now,

Who is keeping back what belongs to the Gods?’

The Brahmin suddenly points to Mokshada

And cries, ‘This woman is the one, she made

Her own son over to the Gods and now

She tries to steal him back.’ “Throw him overboard,”

Scream the passengers with one voice, heartless

In their terror. ‘O grandfather,’ cries Mokshad,

‘Spare him, spare him.’ With all her heart

And might she squeezes Rakhal to her breast.

‘Am I your saviour?’ barks Maitra, his voice

Rising in reproach and bitterness. ‘You stupidly

Thoughtlessly gave your own son

To the Gods in your anger, and now you expect me

To save him! Pay the Gods your debt –

All these people will drown if you break

Your word.’ ‘I am a foolish ignorant

Woman,’ says Mokshada: O God, O reader

Of our innermost thoughts, is what I say

In the heat of anger my true word?

Did you not see how far from the truth

It was, O Lord? Do you only listen

To what our mouths say? Do you not hear

The true message of a mother’s heart?’

But as they speak the boatman and oarsmen

Roughly tear Rakhal from his mother’s clasp.

Maitra turns his face away, shuts his eyes,

Blocks his ears, grits his teeth.

A sharp cry sears his heart like a whiplash

Of lightning, stings like a scorpion – ‘Aunt Annada,

Aunt Annada, Aunt Annada!’ that helpless, hopeless

Drowning cry stabs Maitra’s tightly

Shut ears like a spike of fire. ‘Stop!’

He bursts out, ‘Save him, save him, savehim!’

For an instant he stares at Mokshada lying senseless

At his feet; then he turns to the water. The boy’s

Agonised eyes show briefly among the frothing

Waves as he splutters ‘Aunt Annada’ for the last

Time before the black depths claim him. Only

His frail fist sticks up once in a final

Pathetic grasp at the sky’s protection,

But it slips away again, defeated. The Brahmin

Gasping ‘I shall bring you back,’ leaps

Into the water. He is seen no more. The sun sets.

4. Talitha

Marge Piercy (born 1936)

1. To be of use

The people I love the best

jump into work head first

without dallying in the shallows

and swim off with sure strokes almost out of sight.

They seem to become natives of that element,

the black sleek heads of seals

bouncing like half-submerged balls.

I love people who harness themselves, an ox to a heavy cart,

who pull like water buffalo, with massive patience,

who strain in the mud and the muck to move things forward,

who do what has to be done, again and again.

I want to be with people who submerge

in the task, who go into the fields to harvest

and work in a row and pass the bags along,

who are not parlor generals and field deserters

but move in a common rhythm

when the food must come in or the fire be put out.

The work of the world is common as mud.

Botched, it smears the hands, crumbles to dust.

But the thing worth doing well done

has a shape that satisfies, clean and evident.

Greek amphoras for wine or oil,

Hopi vases that held corn, are put in museums

but you know they were made to be used.

The pitcher cries for water to carry

and a person for work that is real.

2. A work of artifice

The bonsai tree

in the attractive pot

could have grown eighty feet tall

on the side of a mountain

till split by lightning.

But a gardener

carefully pruned it.

It is nine inches high.

Every day as he

whittles back the branches

the gardener croons,

It is your nature

to be small and cozy,

domestic and weak;

how lucky, little tree,

to have a pot to grow in.

With living creatures

one must begin very early

to dwarf their growth:

the bound feet,

the crippled brain,

the hair in curlers,

the hands you

love to touch.

5. Preeti

Adrienne Rich (1929 – 2012)

1. What Kind of Times Are These

There's a place between two stands of trees where the grass grows uphill

and the old revolutionary road breaks off into shadows

near a meeting-house abandoned by the persecuted

who disappeared into those shadows.

I've walked there picking mushrooms at the edge of dread, but don't be fooled

this isn't a Russian poem, this is not somewhere else but here,

our country moving closer to its own truth and dread,

its own ways of making people disappear.

I won't tell you where the place is, the dark mesh of the woods

meeting the unmarked strip of light—

ghost-ridden crossroads, leafmold paradise:

I know already who wants to buy it, sell it, make it disappear.

And I won't tell you where it is, so why do I tell you

anything? Because you still listen, because in times like these

to have you listen at all, it's necessary

to talk about trees.

(2002)

Listen to Adrienne Rich reading this poem:

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/poetryeverywhere/rich.html

2. Dreamwood

In the old, scratched, cheap wood of the typing stand

there is a landscape, veined, which only a child can see

or the child’s older self, a poet,

a woman dreaming when she should be typing

the last report of the day. If this were a map,

she thinks, a map laid down to memorize

because she might be walking it, it shows

ridge upon ridge fading into hazed desert

here and there a sign of aquifers

and one possible watering-hole. If this were a map

it would be the map of the last age of her life,

not a map of choices but a map of variations

on the one great choice. It would be the map by which

she could see the end of touristic choices,

of distances blued and purpled by romance,

by which she would recognize that poetry

isn’t revolution but a way of knowing

why it must come. If this cheap, mass-produced

wooden stand from the Brooklyn Union Gas Co.,

mass-produced yet durable, being here now,

is what it is yet a dream-map

so obdurate, so plain,

she thinks, the material and the dream can join

and that is the poem and that is the late report.

(1987)

6. Joe

Pablo Neruda (1904 – 1973) – Twenty Poems of Love and A Song of Despair

Poem 1. (translated by Joe)

Body of woman, white hills, white thighs,

lying in sweet surrender;

My rough peasant’s body ploughs into you,

spawning an heir from the depths of your feminine.

I was alone in a tunnel. The birds had fled,

and I was crushed by the force of the night.

To survive my ordeal I forged you like a weapon,

You were bow to my arrow, sling to my stone.

Now comes the wanton hour to make love.

Love your body of skin, of moss, of eager, firm, breasts.

Oh those milky globes! The absent look in your eyes!

The pink of the pubes! Your voice, slow and sad!

Body of my woman, I shall pursue you,

Thirsty, aching with boundless desire, yet hesitant!

Those dark passages will not allay my hunger, I know,

Tristesse will follow, and the infinite ache of sex.

Poem 20. (Joe's heavily modified version of W.S. Merwin's translation)

Tonight I can write the saddest lines.

Write, for example, “The night is starry,

The stars are blue and sparkle in the distance.”

The night wind whirls in the sky and moans.

Tonight I can write the saddest lines.

I loved her, and perhaps she loved me too.

On nights like this I held her in my arms.

I kissed her over and again under the endless sky.

She loved me, I must have loved her too.

How could one not have loved those large, tranquil eyes?

Tonight I can write the saddest lines.

To think that I no longer have her. To feel that I have lost her.

To hear the vast night, grow vaster still without her.

And the verses sinking on my soul, as the dew on pasture.

What does it matter that my love could not hold her?

The night is filled with stars but she is not with me.

This is all. In the distance someone sings. Far off.

My soul is unhappy that I can no longer talk to her.

In my mind’s eye I hope to discover and bring her closer.

My heart looks for her, but she is not with me.

On such a night the trees were pale and white

But we who watched it then — are no longer the same.

How much I loved her!

The wind would carry my voice to caress her ears.

She will belong to another now. Another. As it was before I kissed her.

Her voice, her bright body. Her inexhaustible eyes.

I do not love her now, but maybe I do love her.

Love’s so brief, forgetting so prolonged.

On nights like this I held her in my arms;

Now my soul is sad I can no longer talk to her.

Though this is the last pain that she can cause,

… and these the last verses I write for her.

7. Sunil

Anne Sexton (1928–1974)

1. 45 Mercy Street

In my dream,

drilling into the marrow

of my entire bone,

my real dream,

I'm walking up and down Beacon Hill

searching for a street sign -

namely MERCY STREET.

Not there.

I try the Back Bay.

Not there.

Not there.

And yet I know the number.

45 Mercy Street.

I know the stained-glass window

of the foyer,

the three flights of the house

with its parquet floors.

I know the furniture and

mother, grandmother, great-grandmother,

the servants.

I know the cupboard of Spode

the boat of ice, solid silver,

where the butter sits in neat squares

like strange giant's teeth

on the big mahogany table.

I know it well.

Not there.

Where did you go?

45 Mercy Street,

with great-grandmother

kneeling in her whale-bone corset

and praying gently but fiercely

to the wash basin,

at five A.M.

at noon

dozing in her wiggy rocker,

grandfather taking a nap in the pantry,

grandmother pushing the bell for the downstairs maid,

and Nana rocking Mother with an oversized flower

on her forehead to cover the curl

of when she was good and when she was...

And where she was begat

and in a generation

the third she will beget,

me,

with the stranger's seed blooming

into the flower called Horrid.

I walk in a yellow dress

and a white pocketbook stuffed with cigarettes,

enough pills, my wallet, my keys,

and being twenty-eight, or is it forty-five?

I walk. I walk.

I hold matches at street signs

for it is dark,

as dark as the leathery dead

and I have lost my green Ford,

my house in the suburbs,

two little kids

sucked up like pollen by the bee in me

and a husband

who has wiped off his eyes

in order not to see my inside out

and I am walking and looking

and this is no dream

just my oily life

where the people are alibis

and the street is unfindable for an

entire lifetime.

Pull the shades down -

I don't care!

Bolt the door, mercy,

erase the number,

rip down the street sign,

what can it matter,

what can it matter to this cheapskate

who wants to own the past

that went out on a dead ship

and left me only with paper?

Not there.

I open my pocketbook,

as women do,

and fish swim back and forth

between the dollars and the lipstick.

I pick them out,

one by one

and throw them at the street signs,

and shoot my pocketbook

into the Charles River.

Next I pull the dream off

and slam into the cement wall

of the clumsy calendar

I live in,

my life,

and its hauled up

notebooks.

2. As It Was Written

Earth, earth,

riding your merry-go-round

toward extinction,

right to the roots,

thickening the oceans like gravy,

festering in your caves,

you are becoming a latrine.

Your trees are twisted chairs.

Your flowers moan at their mirrors,

and cry for a sun that doesn't wear a mask.

Your clouds wear white,

trying to become nuns

and say novenas to the sky.

The sky is yellow with its jaundice,

and its veins spill into the rivers

where the fish kneel down

to swallow hair and goat's eyes.

All in all, I'd say,

the world is strangling.

And I, in my bed each night,

listen to my twenty shoes

converse about it.

And the moon,

under its dark hood,

falls out of the sky each night,

with its hungry red mouth

to suck at my scars.

3. Young

A thousand doors ago

when I was a lonely kid

in a big house with four

garages and it was summer

as long as I could remember,

I lay on the lawn at night,

clover wrinkling over me,

the wise stars bedding over me,

my mother's window a funnel

of yellow heat running out,

my father's window, half shut,

an eye where sleepers pass,

and the boards of the house

were smooth and white as wax

and probably a million leaves

sailed on their strange stalks

as the crickets ticked together

and I, in my brand new body,

which was not a woman's yet,

told the stars my questions

and thought God could really see

the heat and the painted light,

elbows, knees, dreams, goodnight.

7. Priya

Poems of Spring by Shakespeare, Hopkins, Elfriede Jelinek, Thomas Nashe, Amy Gerstler

1. William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616)

When daisies pied and violets blue

And lady-smocks all silver-white

And cuckoo-buds of yellow hue

Do paint the meadows with delight,

The cuckoo then, on every tree,

Mocks married men; for thus sings he:

“Cuckoo;

Cuckoo, cuckoo!” O, word of fear,

Unpleasing to a married ear!

When shepherds pipe on oaten straws,

And merry larks are ploughmen's clocks,

When turtles tread, and rooks, and daws,

And maidens bleach their summer smocks,

The cuckoo then, on every tree,

Mocks married men; for thus sings he,

“Cuckoo;

Cuckoo, cuckoo!” O, word of fear,

Unpleasing to a married ear!

When icicles hang by the wall,

And Dick the shepherd blows his nail,

And Tom bears logs into the hall,

And milk comes frozen home in pail,

When blood is nipp'd, and ways be foul,

Then nightly sings the staring-owl,

“Tu-who;

Tu-whit, tu-who!”—a merry note,

While greasy Joan doth keel the pot.

When all aloud the wind doth blow,

And coughing drowns the parson's saw,

And birds sit brooding in the snow,

And Marian's nose looks red and raw,

When roasted crabs hiss in the bowl,

Then nightly sings the staring owl,

“Tu-who;

Tu-whit, tu-who!”—a merry note,

While greasy Joan doth keel the pot.

2. Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844 – 1889)

Spring

Nothing is so beautiful as Spring –

When weeds, in wheels, shoot long and lovely and lush;

Thrush’s eggs look little low heavens, and thrush

Through the echoing timber does so rinse and wring

The ear, it strikes like lightnings to hear him sing;

The glassy peartree leaves and blooms, they brush

The descending blue; that blue is all in a rush

With richness; the racing lambs too have fair their fling.

What is all this juice and all this joy?

A strain of the earth’s sweet being in the beginning

In Eden garden. – Have, get, before it cloy,

Before it cloud, Christ, lord, and sour with sinning,

Innocent mind and Mayday in girl and boy,

Most, O maid’s child, thy choice and worthy the winning.

3. Elfriede Jelinek (born 1946)

Spring

april breath

of boyish red

the tongue crushes

strawberry dreams

hack away wound

and wound the fountain

and on the mouth

perspiration white

from someone's neck

a little tooth

has bit the finger

of the bride the

tabby yellow and sere

howls

the red boy

from the gable flies

an animal hearkens

in his white throat

his juice runs down

pigeon thighs

a pale sweet spike

still sticks

in woman white

lard

an april breath

of boyish red

(Translated by Michael Hofmann)

4. Thomas Nashe (1567 – ca 1601)

Spring, the sweet spring

Spring, the sweet spring, is the year’s pleasant king,

Then blooms each thing, then maids dance in a ring,

Cold doth not sting, the pretty birds do sing:

Cuckoo, jug-jug, pu-we, to-witta-woo!

The palm and may make country houses gay,

Lambs frisk and play, the shepherds pipe all day,

And we hear aye birds tune this merry lay:

Cuckoo, jug-jug, pu-we, to-witta-woo!

The fields breathe sweet, the daisies kiss our feet,

Young lovers meet, old wives a-sunning sit,

In every street these tunes our ears do greet:

Cuckoo, jug-jug, pu-we, to witta-woo!

Spring, the sweet spring!

5. Amy Gerstler (born 1956)

In Perpetual Spring

Gardens are also good places

to sulk. You pass beds of

spiky voodoo lilies

and trip over the roots

of a sweet gum tree,

in search of medieval

plants whose leaves,

when they drop off

turn into birds

if they fall on land,

and colored carp if they

plop into water.

Suddenly the archetypal

human desire for peace

with every other species

wells up in you. The lion

and the lamb cuddling up.

The snake and the snail, kissing.

Even the prick of the thistle,

queen of the weeds, revives

your secret belief

in perpetual spring,

your faith that for every hurt

there is a leaf to cure it.

Full

Account of the Poetry Reading on Feb 11, 2015

Present: Pamela, Preeti, Joe, Talitha, KumKum, Gopa, Sunil, Priya

Absent: Ankush (train arrived 4 hours late), Govind (off to Delhi), Mathew (he was on tour, to Hyderabad), Sreelatha (cancelled last minute for family obligation), Zakia (out of town), Kavita (did not respond), Thommo (did not respond)

The next reading for the novel Light in August by William Faulkner has been fixed already for Fri Mar 27, 2015. Sunil requested if possible for the reading sessions to be on a fixed Friday of the month. So far we have been polling readers at each session to establish the best date for the next month, preferably on a Friday, excepting the third (Sunil & CJ have a séance on that day).

1. Pamela

Maya Angelou (1928 – 2014)

The following excerpt is taken from her biography on the Poetry Foundation's website:

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/maya-angelou

“Maya Angelou was an acclaimed American poet, storyteller, activist, and autobiographer. Her career spanned that of -a singer, dancer, actress, composer, and Hollywood's first female black director, but is most famous as a writer, editor, essayist, playwright, and poet. As a civil rights activist, Angelou worked for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. In 2000, Angelou was awarded the National Medal of Arts by President Bill Clinton. In 2010, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honour in the U.S., by President Barack Obama.

Angelou’s most famous work, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969), deals with her early years in Long Beach, St. Louis and Stamps, Arkansas, where she lived with her brother and paternal grandmother. She was first cuddled then raped by her mother's boyfriend when she was just seven years old.

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings is the first of Angelou’s six autobiographies. It is widely taught in schools, though it has faced controversy over its portrayal of race, sexual abuse and violence.

It took Angelou 15 years to write the final volume of her autobiography, A Song Flung up to Heaven (2002).

Angelou was also a prolific and widely-read poet, and her poetry has often been lauded more for its depictions of black beauty, the strength of women, and the human spirit; criticizing the Vietnam War; demanding social justice for all—than for its poetic virtue. basic survival."

She was the first black woman to have a screenplay (Georgia, Georgia) produced in 1972. She was honoured with a nomination for an Emmy award for her performance in Roots in 1977. In 1979, Angelou helped adapt her book, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, for a television movie of the same name.

One source of Angelou's fame in the early 1990s was President Bill Clinton's invitation to write and read the first inaugural poem. Americans all across the country watched as she read On the Pulse of Morning, which begins A Rock, a River, a Tree and calls for peace, racial and religious harmony, and social justice for people of different origins, incomes, genders, and sexual orientations.

Angelou’s poetry often benefits from her performance of it: Angelou recites her poems before spellbound crowds. Indeed, Angelou’s poetry can also be traced to African-American oral traditions like slave and work songs, especially in her use of personal narrative and emphasis on individual responses to hardship, oppression and loss.”

Pam liked the last two lines of Touched by an Angel:

Yet it is only love

which sets us free.

Joe observed there are two characteristics of love emphasised in the poem: its ability to strike the chains of fear from a person, and its ability to set the person free. Customarily, it is truth that is claimed to set us free, as in John 8:32, in the words of Jesus

you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free

Indeed, love can often enslave one to an earthly lover. Sheila said if you substitute the word God for love (since God is love), then the two claims are comprehensible. But Priya asked if God is substituted, the poem becomes limited in the scope of its appeal to theists. Should the poem not make just as much sense to atheists, she asked? Sunil chimed in by adding that surely atheists are capable of love. And why should humans associate love only with God? Gopa 'totally agreed' with Angelou, she said.

2. Sheila Cherian

Iris Hesselden

Sheila Cherian read an inspirational poem is as the last two lines state, to have fortitude in the face of life's troubles:

Be strong and be cheerful in all of life's storms,

And learn how to dance in the rain!

Who is the author, Joe asked; Sheila did not know. She got this poem by copying from a Scottish magazine. KumKuum said Joe used to go merrily dancing in the rain with the children when the monsoon burst over Delhi, sending up the scent of dry earth wetted by the torrent of rain. There was universal acclaim for the poem when Sheila finished reading it. KumKum called it 'sweet and simple' and Priya said it was 'encouraging, hopeful.' Sheila said it was a good poem to read when one is depressed or discouraged by circumstances, for it urges the reader to

Go forward with courage and follow your star,

And leave past misfortunes behind.

3. Gopa & KumKum (duet)

Rabindranath Tagore

KumKum and Gopa read alternate sections of a long poem by Rabindranath, Devoured by the Gods. KumKum gave the gist of the poem by way of introduction. She commented in passing that Bongis eat food with their fingers, but without staining the palm of their hand with the food, and contrasted it with what she considered the uncivilised way in which Malayalees (her husband, for instance) would pitch into pootu and payam or some other dish with gusto, massaging the food with the entire hand; she made an imitative hand gesture saying 'kuchoo, kuchoo.' She went to the extent of noting that when Keralites went outside Kerala they acquired more civilised manners at table. Talitha drew the conclusion then we must all be benighted folk living here in Kerala!

When the poem was finished Joe thought it could be better enacted on the stage, since it is a dramatic poem with several voices. KumKum said William Radice, the translator, turned it into an opera in English and staged it. It seems Rabindranath wrote many poems as little dramas to be produced on stage.

Pamela addressed Talitha to ask if it were not like Jonah's story in the Bible. Talitha answered, no, because he was going some place else. Priya then compared it to the poem Lord Ullin's Daughter where a chieftain makes off with the daughter of the Lord, with the Lord's men in chase:

A chieftain, to the Highlands bound,

Cries, ``Boatman, do not tarry!

And I'll give thee a silver pound

To row us o'er the ferry!''--

It all ends in grief as the storm overtakes them and the Lord discovers his child drowned in the storm:

One lovely hand she stretch'd for aid,

And one was round her lover.

KumKum said Rabindranath wrote this poem to counter the superstitious beliefs that surrounded the lives of ordinary folk, and they are willing to appease a storm god by sacrificing a person. Gopa too agreed that many of his poems were about the absurdity of blind faith. KumKum said Rabindranath was a Brahmo in belief and tried to open people’s eyes to the curse of a life lived in superstition.

Talitha, however, read the poem as being too understated to convey a strong condemnation of such childish beliefs; he seems to sympathise with the human sacrifice. Rabindranath was against many patriarchal customs among Hindus of the time, e.g., forbidding widows from remarrying, considering widows such bad luck that they have to be kept out of sight at festivals. Gopa said in Bengal suttee was common. Priya mentioned the export of widows to Benares. Gopa said if you are a Vaishnavite in Bengal, then a widow is encouraged to spend her time in Mathura-Brindavan as the sites of Lord Krishna. Sunil and others think the practice is more like abandonment, rather than widows voluntarily going away to lead a life of renunciation.

Talitha wished the poem were read in Bengali and they could follow with some knowledge of Sanskrit what was going on. I do not think Bengali is so easily comprehended, particularly the poetic Bengali of Rabindranath.

4. Talitha

Marge Piercy

You can read an extensive biographical note at Poetry Foundation:

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/marge-piercy

She has published 17 volumes of poetry and written as many novels. She was born in Detroit of Lithuanian Jewish descent. “Piercy’s poetry is known for its highly personal, often angry and very emotional timbre. She writes a swift free verse that shows the same commitment to the social and environmental issues that fill her novels.” Her love of books originated from a the time she suffered a bout of rheumatic fever in childhood. Her mother read voraciously and encouraged her daughter to do the same.

Her work shows commitment to the dream of social change (what she might call, in Judaic terms, tikkun olam, or the repair of the world), rooted in story, the wheel of the Jewish year, and a range of landscapes and settings. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marge_Piercy )

She has been married three times and now lives in Cape Cod. The first poem, A work of artifice, talks of the oppression of women:

one must begin very early

to dwarf their growth:

the bound feet,

the crippled brain,

the hair in curlers,

the hands you

love to touch.

Joe told of his horror at seeing the trees in front of the Emperor's Palace in Central Tokyo, the branches being twisted and curled and bound in strong wires, in order to make the trees grow in an arbitrary human-imposed fashion. Talitha spoke of a creative exercise to read Ibsen's The Doll's House, and then giving this poem to get the reactions of students. The similarities came out in excellent ways, she said.

The second poem, To be of use, extols work and the ideal of being immersed in work. Gopa wondered if this was a Calvinist attitude to work. Talitha referred to the different images of work – jumping into work head first, persisting in hard work and toiling in the mud to move things forward a little. There is even beauty in it:

.. the thing worth doing well done

has a shape that satisfies, clean and evident.

5. Preeti

Adrienne Rich

Powell, a fellow poet, recounted how Rich in a poem titled What Kind of Times Are These, dwelled on a patch of grass in the space between two stands of trees as she mulled a sense of collective fear in 2002, leading up to the US-led invasion of Iraq.

"She's thinking about how people disappear, and how we're living in a country that's so full of dread," Powell said. "But she's not talking about war. She's talking about it in the language of houses and shadows and leaf mould." (D.A. Powell, see

http://uk.reuters.com/article/2012/03/29/uk-rich-obit-idUKBRE82S04420120329

For a review of her life when she died in 2012 see the article titled Adrienne Rich, feminist poet who wrote of politics and lesbian identity, dies at 82:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/books/adrienne-rich-feminist-poet-who-wrote-of-politics-and-lesbian-identity-dies-at-82/2012/03/28/gIQAQygghS_story.html

Adrienne Rich was a feminist poet and critic. She worked in the Civil Rights movement and got a young poets award. She deals in archetypal female figures. The Poetry Foundation bio of hers is perceptive and does justice to her varied activities and political stances:

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/adrienne-rich

Preeti quoted the poet's conception of what a poem is: (need a quotation from Preeti)

Adrienne Rich also uses the powerful imagery of the atom bomb. Joe commented about the poem What Kind of Times Are These, that the word disappear occurs three times, forming a motif. The poem was written in 2002, well after 9-11 and the looming Iraq War which is the backdrop.

One senses the anticipation of the illegal renditions and so on which made America look like a new Soviet Union; people are sent to black holes like Guantanamo, and then no habeas corpus can save them from inhuman treatment and torture, administered in secrecy.

Joe referred to an excellent book authored by Mohamedou Ould Slahi - writer of the Guantanamo Diary, detained without charge and without trial for a decade and more:

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/15/books/review/guantanamo-diary-by-mohamedou-ould-slahi.html

Guantanamo Diary reads like Kafka's The Trial. Mr. Slahi emerges from the pages of his diary, handwritten in 2005, as a curious and generous personality, observant, witty and devout, but by no means fanatical. More about him and his editor, Larry Siems, are at

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jan/29/guantanamo-diary-detainee-new-york-times-bestselling-author

Excerpts read by famous authors are here below; please listen to Stephen Fry and Peter Serafinowicz:

http://guantanamodiary.com

Talitha commented on the deliberate vagueness of the second poem, Dreamwood. Preeti said as children we see patterns in moss, shadows, etc. Sunil agreed that daydreaming in class was constant. There is a typing stand, a woman typing a report and seeing patterns

… she would recognize that poetry

isn’t revolution but a way of knowing

why it must come.

6. Joe

Pablo Neruda

Pablo Neruda was a Chilean poet who was born to a working-class family in 1904 in a small town in S Chile. His mother died when he was young. When he showed early interest in poesy his father was exasperated enough to forbid him to write in the family name; so he adopted the name by which he is known and it became his legal name.

He moved to the capital city of Santiago and published his first collection, Book of Twilight, in 1923. Indeed Neruda brought his work to the principal of the local girls' school, the famed poet Gabriela Mistral (she won the Nobel for Lit in 1945), who told him: "I was sick, but I began to read your poems and I've gotten better, because I am sure that here there is indeed a true poet."

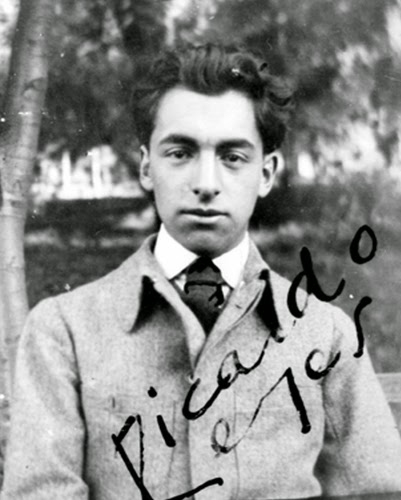

Gabriela Mistral

He followed it a year later with a thin collection called Veinte Poemas de Amor (Twenty Poems of Love), to which he added a longer poem called Una Canción Desesperada (A song of despair). This collection instantly catapulted him to fame. It is the first poetry in Spanish that unabashedly celebrates erotic love in sensuous, earthly terms. "Love poems were breaking out all over my body," he later recalled.

His example shows like that of many other poets the importance of giving voice to one's literary talent as early as possible. What you could write then, may lack maturity, but the feelings and experiences of that spring time of one’s existence can never be recaptured in maturity. They will have an abandon, a freshness, a boldness, and an originality of voice which will be at the height of their strength. How strong you can imagine from the fact this collection has sold over two million copies and has been translated into all major languages, and in English itself there must be a dozen writers and poets who have attempted to translate them. K Satchidananadan and Balachandran Chullikkad have translated some poems of his into Malayalam. Marquez considered Neruda the great voice of poetry from S America, calling Neruda "the greatest poet of the 20th century in any language.” This is not to forget all the other great voices like Gabriela Mistral, Ruben Dario, Octavio Paz, Jorge Luis Borges, Cesar Vallejo, Juana Inés de la Cruz , and so on.

He had a colourful life: ambassador of Chile in several countries, visits to Europe, membership in the Communist Party, an ardent supporter of the Republican cause in Spain during the time the fascists under Gen Franco were making the country into a a dictatorship with help from the Nazis. He worked for the election of Salvador Allende in Chile, a socialist, and when Gen Pinochet overthrew the elected government with US help, he was bitterly disappointed, and withdrew to a corner of Chile and died soon after in 1973. You can read the wiki to get an extensive biography. His complete works are in three volumes, 3,522 pages long.

I know Neruda has been recited three times before, but why Veinte Poemas never figured I can’t tell. I will make good that deficit by reading a couple of poems from the collection. They are erotic, there’s no doubt, and when he was asked, he admitted to two girls being responsible for the evocation in the poems, Marisol and Marisombra. The world has to thank them. The translations are mine. I have used the translation of W. S. Merwin (Penguin, 1969) as a crib. It’s available on the Web. I have taken considerable liberties with the Spanish text to make the heavily symbolic and sometimes veiled references to sex more explicit. I hope I have made them less dense in the process. Please excuse the sacrilege.

Talitha commented on 'rough peasant's body,' a self-description of the poet. Neruda probably had a soft body, she opined! Priya said the poet stands out as a lover. KumKum who distrusts erotic love, said a woman is foolish to be loved by someone like Neruda. The point is we do not know how much is fiction and how much is derived from reality in any poem, even if the poem uses the personal pronoun. Sunil liked the line:

Love’s so brief, forgetting so prolonged.

Joe was teased for his choice of this kind of passionate poem, or the second one which is a poem of longing for what is past. But how many poets can boast of a slight book that is still in print a century later, and has sold two million copies?

7. Sunil

Anne Sexton

Sunil said Anne Sexton was a manic-depressive and poetry was recommended by her therapist as form of healing. One day after readying her latest volume for the press, she went to the garage, turned on the car's engine, and died by carbon monoxide poisoning. She is buried in Forest Hills cemetery in Ballston, MA. You can read a good bio of hers at

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/anne-sexton

In the poem 45 Mercey Street she is looking for comfort from the past, recalling her family home. Sunil said it is a simple and innocent part of her life. KumKum liked the poem Young and Priya said it was a good one:

A thousand doors ago

when I was a lonely kid

in a big house with four

garages and it was summer

as long as I could remember,

I lay on the lawn at night,

clover wrinkling over me,

the wise stars bedding over me,

7. Priya

Poems of Spring by Shakespeare, Hopkins, Elfriede Jelinek, Thomas Nashe, Amy Gerstler

Priya was taken by the fact that the season of basant is round the corner and chose various poems from Middle English times to the present, celebrating spring. Shakespeare in his pastoral mood is simple and nostalgic, but the call of the cuckoo reminds him of cuckolded husbands. Hopkins is always a bit on the religious side:

What is all this juice and all this joy?

A strain of the earth’s sweet being in the beginning

In Eden garden.

Before the spring is lost let's taste it, he says.

Elfriede Jelinek lost her family in the Holocaust. She was a member of the Communist Party and took up writing as a therapy. There was a movement of protest against her getting the Nobel for Literature in 2004. Her poem is opaque; perhaps the trouble is with the translation, thought Talitha.

Amy Gerstler's poem, In Perpetual Spring, was read to great acclaim! Sunil liked the lines:

in search of medieval

plants whose leaves,

when they drop off

turn into birds

Everyone liked the ending:

your faith that for every hurt

there is a leaf to cure it.

It was a very appealing poem.

The Poems

1. Pamela

Maya Angelou (1928 – 2014)

1. Touched by an Angel

We, unaccustomed to courage

exiles from delight

live coiled in shells of loneliness

until love leaves its high holy temple

and comes into our sight

to liberate us into life.

Love arrives

and in its train come ecstasies

old memories of pleasure

ancient histories of pain.

Yet if we are bold,

love strikes away the chains of fear

from our souls.

We are weaned from our timidity

In the flush of love's light

we dare be brave

And suddenly we see

that love costs all we are

and will ever be.

Yet it is only love

which sets us free.

2. Caged Bird

A free bird leaps

on the back of the wind

and floats downstream

till the current ends

and dips his wing

in the orange sun rays

and dares to claim the sky.

But a bird that stalks

down his narrow cage

can seldom see through

his bars of rage

his wings are clipped and

his feet are tied

so he opens his throat to sing.

The caged bird sings

with a fearful trill

of things unknown

but longed for still

and his tune is heard

on the distant hill

for the caged bird

sings of freedom.

The free bird thinks of another breeze

and the trade winds soft through the sighing trees

and the fat worms waiting on a dawn bright lawn

and he names the sky his own

But a caged bird stands on the grave of dreams

his shadow shouts on a nightmare scream

his wings are clipped and his feet are tied

so he opens his throat to sing.

The caged bird sings

with a fearful trill

of things unknown

but longed for still

and his tune is heard

on the distant hill

for the caged bird

sings of freedom.

2. Sheila Cherian

Iris Hesselden

Dance in the Rain

Life isn't just waiting for storm clouds to pass,

It's learning to dance in the rain,

It's looking for rainbows and seeking for joy

And knowing that love will remain.

This life has its problems, its worries and woes,

And each of us must take our share,

But look to the seasons and all they can give,

There's beauty around everywhere.

And seek for the wonder, the laughter and love,

The friendship to warm heart and mind,

Go forward with courage and follow your star,

And leave past misfortunes behind.

Hold fast to your hopes and keep them all safe,

Your daydreams are never in vain;

Be strong and be cheerful in all of life's storms,

And learn how to dance in the rain!

3. Gopa & KumKum (duet)

Rabindranath Tagore (1861 – 1941)

DEBOTAAR GRASH: Devoured by the Gods

The news has gradually spread around the villages –

The Brahmin Maitra is going on a pilgrimage

To the mouth of the ganges to bathe. A party

Of travelling companions has assembled – old

And young, men and women; his two

Boats are ready at the landing stage.

Moksada too is eager for merit –

She pleads, ‘Dear grandfather, let me come with you.’

Her plaintive young widow’s eye cannot see reason;

She entreats him, she is hard to resist. ‘There is no

More room,’ says Maitra. ‘I implore you at your feet.’

She replies, weeping – ‘I can find space

For myself somewhere in a corner.’ The Brahmin’s

Mind softens, but he still hesitates

And asks, ‘But what of your little boy?’

‘Rakhal?’ says Mokshada, ‘he can stay

With his aunt. After he was born I was ill

For a long time with puerperal fever, they despaired

Of my life; Annada took my baby

And suckled him along with her own – she gave him

Such love that ever since then, the boy

Has preferred his aunt’s lap to mine. He is so

Naughty, he listens to no one – if you try

And tell him off, his aunt comes

And draws him to her breast and weeps and cuddles him.

He will be happier with her than with me.’

Maitra gives in. Moksada immediately

Hurries to get ready – packs her things,

Pays respect to her elders, floods

Her friends with tearful goodbyes. She returns

To the landing-stage – but whom does she see there?

Rakhal, sitting calmly and happily

On board the boat – he has run there ahead of her.

‘What are you doing here?’ She cries. He answers,

‘I’m going to the sea.’ ‘You are going to the sea?’

Says his mother, ‘You naughty, naughty boy,

Come down at once.’ His look is determined,

He says again, ‘I’m going to the sea.’

She grabs his arm, but the more she pulls

The more he clings to the boat. In the end

Maitra smiles and says tenderly, ‘Let him be,

He can come along.’ His mother flares up-

‘All right, then, come,’ she snaps,

‘The sea can have you!’ The moment these words

Reach her own ears, her heart cries out,

Repentance runs through it like an arrow; she clenches

Her eyes and murmurs, ‘God, God’;

She takes her son in her arms, covers him

With loving caresses, blesses him, prays for him.

Maitra draws her aside and whispers,

‘For shame, you must never say such things.’

Suddenly Annada rushes up – people

Have told her that Rakhak has been allowed

To go with the boats. ‘My darling,’ she cries,

‘Where are you going?’ ‘I’m going to the sea,’

Says Rakhal cheerfully, ‘but I will come back again,

Aunt Annada.’ Nearly mad, she shouts at Maitra,

‘But who will control him, he is such a mischievous

Boy, my Rakhal! From the day he was born

He has never been away from his aunt for long-

Where are you taking him? Give him back!’

‘Aunt Annada,’ says Rakhal, I’m going to the sea,

But I’ll come back again.’ The Brahmin says kindly,

Soothingly, ‘So long as Rakhal is with me

You need not fear for him, Annada. It is winter,

The rivers are calm, there are many other

Pilgrims going – there is no danger

At all. The trip will take two months –

I shall bring your Rakhal back to you.’

At the auspicious time and with prayers

To Durga, the boats set sail. Tearful

Womenfolk stay behind on the shore.

The village by the Churni river seems tearful

Too, with its wintry morning dew.

*

The pilgrimage is over and the pilgrims are returning.

Maitra’s boat is moored to the bank,

Waiting for the afternoon tide. Rakhal,

Curiosity satisfied, whimpers with homesick

Longing for his aunt’s lap. His heart

Is weary of endless expanses of water.

Sleek and glossy, dark and curving

And cruel and mean and spiteful water,

How likw a thousand-headed snake it seems,

So full of deceit, greedy tongues darting,

Hoods readring, mouths foaming as it hisses and roars

And eternally lusts for the children of earth!

O earth, how speechlessly loving you are,

How stable, how certain, how ancient; how smilingly,

Greenly, softly tolerant of all

Upheavals; wherever we are, your invisible

Arms embrace us all, day and night,

Drae us with such huge and rapturous force

Towards your calm, horizon-touching breast!

Every few moments the restless little boy

Comes up to the Brahmin and asks anxiously,

‘Grandfather, when will the tide come?’

Suddenly the still waters stir,

Awaking both banks with hope of departure.

The prow of the boat swings round, the cables

Creak as the current pulls; gurgling,

Singing , the sea enters the river

Like a victory-chariot – the tide has come.

The boatman says his prayers and unleashes

The boat on to the northward-racing stream.

Rakhal comes up to the Brahman and asks,

‘How many days will it take us to get home?’

With four miles gone and the sun still not set

The wind has started to blow more strongly

From the north. At the mouth of the Rupnarayan river,

Where a sandbank narrows the channel, a fierce

Seething battle breaks out between the scurrying

Tide and the north wind. ‘Get the boat to the shore.’

Cry the passengers repeatedly – but where is the shore?

Everywhere whipped up water claps

With a thousand hands, its own mad death- dance:

It jeers at the sky in the furious uprush

Of its foam. On one side are glimpses of the distant

Blue line of the woods on the bank; on the other,

Ravenous, gluttonous, murderous waters

Swell in insolent rebellion against the calm

Setting sun. The rudder is useless

As the boat spins and tumbles like a drunkard.

The men and women aboard tremble

And flounder as icy terror mixes

With the piercing winter wind. Some are dumb

With fear; others yell and wail and weep

For their dear ones. Maitra ashen- faced,

Shuts his eyes and mutters prayers.

Rakhal hides his face in his mother’s breast

And shivers mutely. Desperate now

The boatman calls out to everyone, ‘Someone

Amongst you has cheated the Gods, has not

Given what is owing- hence these waves,

This unseasonal typhoon. I tell you, make good

Your promise now – you must not play games

With angry Gods.’ The passengers throw money,

Clothes, everything they have into the water,

Racking nothing. But the water surges higher,

Starts to gush into the boat. The boatman

Shouts again. ‘I warn you now,

Who is keeping back what belongs to the Gods?’

The Brahmin suddenly points to Mokshada

And cries, ‘This woman is the one, she made

Her own son over to the Gods and now

She tries to steal him back.’ “Throw him overboard,”