Friday 12 April 2024

Slaughterhouse-five by Kurt Vonnegut – Mar 26, 2024

Saturday 16 March 2024

Poetry Session, 26 February, 2024

When readers at KRG choose their poems they cast a wide net. On this occasion we had a Malayalam poet, Edasseri Govindan Nair, represented by a poem. Malayalam poems are usually sung or chanted as chollal, but here it was delivered as the English translation of a modern poem of hope and longing; hope for the future made possible by a new bridge to transform the countryside, and longing for the old days. Other Malayalam poets who have been recited at KRG are K. Satchidanandan, Balachandran Chullikad, O.N.V. Kurup, Sugatha Kumari, Balamani Amma (mother of the poet Kamala Das), Kumaran Asan, and Chemmanam Chacko.

When one of our readers, Kavita, chose the ever popular Maya Angelou, Joe raised the question of who has been the most recited poet at KRG – after William Shakespeare, of course. The answer is Keats (13), then Eliot (11) and numerous Romantic poets with 8 occurrences. But how is it that Rumi, the most widely published poet in modern times, scarcely finds mention in the pages of KRG’s blog? He wrote lines like this (translated by Farrukh Dhondy)

T.S. Eliot, ever popular at KRG was represented by two short poems that did not require the usual annotation to lay bare obscure meanings. In the first poem the poet hears the noise of plates in a basement kitchen rattling somewhere as he gazes on the street from a window, and then

The brown waves of fog toss up to me

Twisted faces from the bottom of the street,

The second poem featured a fictional cousin of modern mores who smokes and dances all the fashionable dances. The poet holds up the censorious sight of Matthew and Waldo (that is, Matthew Arnold and Ralph Waldo Emerson) trained on Nancy Ellicott – not that she cares. The last line (‘The army of unalterable law.’) is taken from another poet, Meredith, but Eliot is contrasting his reference ironically with modern devil-may-care attitudes.

Mary Oliver, the Pulitzer prize-winning poet whose rapturous odes to nature and animal life brought her critical acclaim

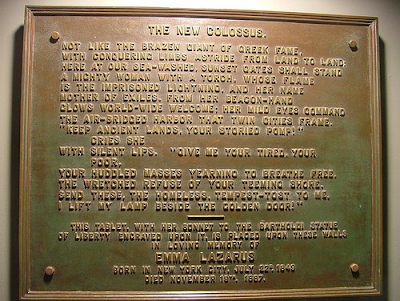

Mary Oliver was another outstanding presence at the session when Saras chose two of her poems. We know her poems from three earlier occasions when she has been presented. She is also the marvellous author of a handbook of poetry, that lays bare the mechanics of how a poem is built, from meter and rhyme, to form and diction, being imbued with sound and sense. Mary Oliver employs wonderful examples, ancient and new, to illustrate her exposition. It will surprise no one that six of the ten poets chosen at this session were women.Most prominent of these is The New Colossus, a Petrarchan sonnet (rhyming abba abba cdc dcd). The entire sonnet is engraved on a plaque at the base of the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbour and lines 10 and 11 are often quoted:

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free

These words are a tribute to the diversity of America, which has been under threat from the masses who seek to enter America from its southern border. The press of poor people entering from Mexico is no longer a welcome sight to Democrats or Republicans. The original Colossus of Rhodes was a towering statue of Helios the sun god, built in 280 BCE to commemorate the defence of Rhodes against the attack of Demetrius. The sonnet of Emma Lazarus contrasts this ancient colossus with the Statue of Liberty presented by France as a symbol of liberty illuminating the world (La Liberté éclairant le monde).

Tuesday 20 February 2024

Mother of 1084 by Mahasweta Devi, Jan 30, 2024

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naxalbari_uprising

Naxalism and Naxalites were terms in use at the time, and spread to some cities, where violence took the form of killing persons in power and snatching rifles from armed policemen deployed to quell the violence on streets. Joe used to live at the time in the area named as relatively calm in the novel (Park Street and Camac Street) but it was common to see policemen holding rifles chained to their waist lest Naxaals attack them and wrest the weapons from their hands.

Mahasweta Devi may not have been violent herself, but her lifelong sympathies were with the tribals whom she worked to educate, uplift, and write about. Why she wrote this novella, at first a play, is no mystery. She wanted to depict the empty veneer of materialism that paraded as culture among educated upper-class urbanites, and contrast it with the idealism of those who revolted and led movements to bring justice to the poor. As she wrote:

“In the seventies, in the Naxalite movement, I saw exemplary integrity, selflessness, and the guts to die for a cause. I thought I saw history in the making, and decided that as a writer it would be my mission to document it. As a writer, I feel a commitment to my times, to mankind, and to myself. I did not consider the Naxalite movement an isolated happening.”

The violence was not only by the government on the Naxal participants; it took place as bloody warfare between opposing groups of leftist partisans which Mahashweta Devi recounts:

“A bloody cycle of interminable assaults and counter-assaults, murders and vendetta, was initiated. The ranks of both the CPI(M) and CPI (M-L) dissipated their militancy in mutual fightings leading to the elimination of a large number of their activists, and leaving the field open to the police and the hoodlums. It was a senseless orgy of murders, misplaced fury, sadistic tortures, acted out with the vicious norms of the underworld, and dictated by the decadent and cunning values of the petit bourgeois leaders.”

In Mother of 1084 (published serially in a periodical in 1973, and later as a novella in 1974) Mahasweta re-enacts the senseless killings of the Naxalites. The author does it evoking the intense love of a mother (Sujata) for her son (Brati) whose motivations and struggles she does not understand. Much of the novel is given to the mother’s search for the secret life of her son with his comrades, including a lover (Nandini) who is tortured by the police to extract information about others in the movement. The third woman who suffers is the mother of Somu, a comrade of Brati, who is also killed in the internecine warfare; but she can wail her loss openly, in a way Sujata cannot.

The passage of time is referred to often in the pages of the novel by the women who bear the suffering of past grief, the unbearable grief of losing a beloved son, and the poignant loss of a comrade in arms at the flowering of his youth.

In the first simile on p.61 Time is likened to the flowing of a river, Grief is the bank of the river where sorrow accumulates. As the river flows, the alluvium carried by the river water is heaped on the accumulated grief on the bank, submerges it, and soon new shoots of hope grow to mitigate the sorrow.

In a second simile on p.77, Time is seen firstly as the compression of loss: the past is gone forever. Secondly time is seen (as above) through the same prism of flowing water carrying fresh alluvial soil to cover the mudbanks of grief heaped by the past. And that brings new hope.

In yet a third simile on p.79, Time is cast as an ‘arch fugitive, always on the run.’ It reminds one of the Latin maxim tempus fugit (time flies) which is shortened from Virgil's Georgics, where it appears as fugit inreparabile tempus: “it escapes, irretrievable time.” In the novel Sujata ‘would never be able to retrieve the moment when Brati in his blue shirt stood at the foot of the stairs.’ Will the two women, Sujata and Nandini, be always in search of lost time, like Swann in Proust’s novel Remembrance of Things Past?

Samik Bandyopadhyay, the translator, says he had the privilege of working with the author who contributed her own notes on the translation.

%20front%20cover,%201974.png)

%20is%20an%20eminent%20Indian%20writer%20and%20social%20activist.%20She%20is%20one%20of%20the%20foremost%20literary%20personalities%20and%20best-selling%20Bengali%20author%20of%20short%20fiction%20and%20novels.png)