Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya is the background to this novel, set in the days after he had taken power in a 1969 coup against the monarchy backed by the West. His aim was to set up and implement an ‘Islamic socialism’, to which end he nationalised the western-controlled oil industry and used the state revenues to bolster the military and implement social programs like housing, healthcare and education. But power corrupts and soon he was in the dire business of squelching dissent internally and funding foreign militants.

The novel is a kind of bildungsroman, and follows the plight of Suleiman, a young boy whose father, though a prosperous import businessman, supports anti-Gaddafi activities. His young mother, Najwa, is his comforter in the home, and outside it, his best friend Kareem and his father’s friend Moosa are the people he can look to for escape from fear and panic.

We are given a historical perspective by Usthath Rashid, a university professor who moves with his son Kareem next door to Suleiman’s home. Libyan history dates to the time when the Phoenicians from present-day Lebanon settled in the north-west corner on the coast, and it was later expanded by the Roman Emperor Septimius Severus to form the port of Leptis Magna (now called Al-Khums) in 200 CE.

The dramatic highpoint of the book is when Usthath Rashid after public interrogations is led to his execution. The crowd are rabid, being incited by the regime to condemn a traitor to Libyan socialism. His own father has disappeared and that too induces a sense of panic in the young Suleiman’s heart. Ultimately, his parents smuggle him off to Cairo where he grows up and becomes a pharmacist under the care of Judge Yaseen, Moosa’s father. The book peters out in Cairo. There is no great return to Libya possible, nor any desire.

Clearly the autocratic regime of Gaddafi and the suppression of dissent are the thrust of the book, showing how it affected ordinary people, and caused the multitudes to fall in line. In the end we have to remember also that Libya was bombed in 1986, supposedly in retaliation against terrorism, and Gaddafi was killed by US, UK, and France acting in concert. They sowed the mayhem and civil war that continues to this day.

In the Country of Men by Hisham Matar

Author bio by Arundhaty Nayar

Hisham Matar was born in New York in 1970 to Libyan parents and spent his childhood first in Tripoli and then in Cairo. He has lived in London since 1986.

Hisham Matar was the second of two sons. His father, Jaballa Matar, who was a political dissident for his opinions on Colonel Muammar Gaddafi’s coup in 1969, had to move the family away from Tripoli and was working for the Libyan delegation to the United Nations, in New York, at the time of Matar's birth.

The family moved back to Tripoli, Libya, in 1973, but fled the country again in 1979. Matar was nine when they moved to Cairo, where the family lived in exile. Matar's father became more vocal against the Gaddafi regime. Matar continued his schooling at Cairo's American school.

In 1982, Matar's brother Ziad left for boarding school in the Swiss Alps. There were continued threats by the Libyan dictatorship against their father, as well as a threat to Ziad's safety while he was studying in Switzerland . Matar continued his schooling at Cairo’s American school. Both boys had to attend the schools under a false identity.

He had to pretend that his mother was Egyptian and his father American. His first name was Bob. His brother Ziad chose the name because both he and Hisham were fans of Bob Marley and Bob Dylan. “I was to pretend I was Christian, though not religious. I was to try to forget my name. If someone called Hisham, I was not to respond.” — Hisham Matar, 2011.

By the time Matar finished his studies, Ziad was a university student in London. Matar decided to pursue his studies in architecture, and later received an MA in Design Futures at Goldsmiths, University of London.

In 1990, while he was still studying in London, his father Jaballa Matar, was abducted in Cairo. He has been reported missing ever since. In 1996, the family received two letters in his father's handwriting stating that he had been kidnapped by the Egyptian secret police, handed over to the Libyan regime, and imprisoned in the notorious Abu Salim prison in the heart of Tripoli.

The letters were the last sign and only thing they had heard from him or about his whereabouts. In 2009, Matar reported that he had received news that his father had been seen alive in 2002, indicating that Jaballa had survived a 1996 massacre of 1200 political prisoners by the Libyan authorities.

In the Country of Men, has been published in twenty-two languages, and was short listed for the Man Booker Prize 2006 and the Guardian First Book Award.

Hisham Matar has won a number of awards for this novel we are reading today, among them Royal Society of Literature Ondaatje Prize for In the Country of Men (2007), Guardian First Book Award for In the Country of Men (2006).

His memoir of the search for his father, The Return, won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography and the 2017 PEN America Jean Stein Book Award.

Matar's essays have appeared in numerous papers like The Independent, The Guardian, The Times and The New York Times. His second novel, Anatomy of a Disappearance, was published to wide acclaim on 3 March 2011. He lives and writes in London.

Il Libro di Dot is a children's book released by Matar in 2017, illustrated by Gianluca Buttolo.

On October 17, 2019, Matar published A Month in Siena. The short book is an affectionate and reflective record of his most recent stay in Siena, Italy and his encounters there with Sienese School artworks.

He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, and Associate Professor of Professional Practice in Comparative Literature, Asia & Middle East Cultures, and English at Barnard College, Columbia University.

Introduction to the Novel by Arundhaty Nayar

In the Country Of Men is ultimately about universal issues: human faults and triumphs, the resilience of the human spirit, the dynamic of relationships between parent and child, friend and neighbour, a country and its citizens.

The novel addresses the issue of loyalty and how various characters experience loyalty and betrayal.

In this story, there are many instances of betrayal by the protagonist, the little boy Suleiman. He knows the faces of the people who took away his neighbour and teacher, his own father’s closest friend, and the father of his friend. Yet he taunts his friend and deserts him. This is on account of fear. He had a strange compulsion to beat one who is already down.

Commentaries on Passages by the Readers

Joe:

The story of this book is about a young boy Suleiman growing up in Libya in the time when Colonel Muammar Gaddafi seized power and ushered in a revolution, and ruled as autocratic leader of the Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya from 1977 to 2011. Revolutionary Committees in his time called the Mokhabarat (intelligence agency) were responsible for policing and suppressing dissent.

Suleiman is from a well-off family. His father Farah is an import businessman and he is the sole son of his doting mother, Najwa. We see him growing up and playing with children of the neighbourhood. He is close to Kareem, the son of a History professor, Ustath Rashid. He also relies on his father’s good friend Moosa.

Leptis Magna – Arch of Septimius Severus

The passage Joe read is taken from an educational tour Ustath Rashid conducts for his university students in which the ancient Roman history of the town called Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) is narrated. Leptis Magna began its existence as a Phoenician city (i.e. of Lebanese origin) in the 7th-century BC and was greatly expanded under the Roman Emperor Septim(i)us Severus who reigned for 18 years from 193-211 CE. The ruins lie 180 km east of Tripoli in Libya.

Roman marble bust of Septimius Severus, early 3rd century AD, Altes Museum

Carthage, 1000 km to the north-west, is situated in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was inaugurated by the famous Phoenician Queen Dido and was the object of a destructive war (the third Punic War) by the Romans who left nothing standing, adhering to the famous slogan Carthago delenda est, in Latin, meaning ‘Carthage must be destroyed’, uttered by Cato, in the Roman senate.

Ruins of Ancient Carthage

During the tour Ustath Rashid recites a verse written in lamentation for Carthage by Sidi Mahrez after seeing its ruins:

Why this emptiness after joy?

Why this ending after glory?

Why this nothingness where once was a city?

Who will answer? Only the wind

Which steals the chantings of priests

And scatters the souls once gathered.

In the final segment Suleiman seeing the marble sculpture of a naked Maenad cannot resist turning his finger ‘round the pink centre of her nipple,’ and kissing her lips. Priya thought it was precocious of Suleiman to have such urgings. Both Saras and Joe disagreed, and said boys do have such fantasies, and nine years is quite past the age of pre-pubescent innocence. They are not babes any more, said Saras. Priya maintained her stance, and Joe responded ‘ladke karthey hain jo ladke karthey hain.’ Arudhaty added that since his mother was telling stories from the Arabian Nights, and the account of how she herself was forcibly married, Suleiman was not growing up in a protected environment, unaware of these things. KumKum mentioned that in the story Suleiman comes to know that on the wedding night of a proper Muslim wedding the bride should bleed into a handkerchief.

Meanwhile Zakia joined from a resort in the Poconos, NY, where she had gone with Abbas on a vacation with their son, Waseem staying on in New York city. It was a place with wild flowers and birds and they were staying in a lovely cottage with a garden.

Saras added that in Kerala the word Ustad is also used to refer to a teacher of the Koran. Joe had pointed out that the word ‘Usthat’ in the novel is what we call an Ustad in our part of the world, where it is used generally to signify a musician or performer who has attained great virtuosity.

Saras:

Saras read from the passage where Suleiman’s father has been taken away by the secret police for the first time. Her sympathy as a reader lay with the mother, Najwa. She was hoping for a bit of independence as a 14-year-old and then she was caught by her brother holding hands with a boy in a restaurant, and everybody’s reaction was to get her married quickly. She is very resentful, being married off to a much older man. She is loyal to him throughout and tries to keep a good household, but it takes an enormous toll on her mental health.

She becomes an alcoholic, and smokes at home. Her son tries to protect her. When her husband is taken away she is ready to do anything to bring him back. Saras thought of Najwa as the courageous woman in the story. In this passage when her husband is taken away for the first time she is letting out all her angst. She is talking to Moosa and her son overhears the conversation.

She is very angry and takes out all her anger on Moosa.

Priya:

Suleiman and Kareem are in this passage. Priya was taken aback by Suleiman’s reaction to Kareem. There is much cruelty around them, and dysfunctional households. How to survive as an individual was central. When they part at the end with Suleiman going off, Kareem does not come to say goodbye. Children can often give hurt without thinking. The book we read, The Lord of the Flies, gives evidence of children’s tendency toward cruelty.

Suleiman did not understand the revolution. His father was involved, but his mother was indifferent to it, as was Suleiman. Although he calls Kareem a traitor, he did not understand the meaning; it was used like a bad word. He repeats what he is hearing. Joe recalled Woody Guthrie’s song This Land Is Your Land, which sounds like the game they are playing, My Land, Your Land.

What started as being a popular revolution degenerated into an autocracy that would brook no opposition internally; a regime that also engineered incidents of terrorism overseas.

Arundhaty:

The passage selected by Arundhaty is such an instance when the little boy betrays his family friend, his father’s secretary, Nasser . The author beautifully depicts the complexity of human psychology through the boys’ behaviour, where he says: ‘I didn’t like him calling me ‘Good boy’ but I had never felt such affection for Nasser as I did now.’

And then he proceeds to divulge information about him to the strange man over the phone. He also discloses the exact building and location where he had seen his own father go and hang out the red cloth through the window. As we read, we cannot help thinking that he knows he is doing wrong and will cause harm to the person, yet he cannot help himself . Why? What comes through is also his desire to please this unknown person . It is difficult to know what was compelling him. Perhaps he wanted to grow into manhood by joining the all-powerful ‘Men’ he saw.

Saras said the crafty interrogators pile on to Suleiman and he is innocent and does not know how to reply or that he should be guarded in his replies in order to protect his friend.

Zakia:

Zakia enjoyed reading this book. She was joining us from a resort in the Pocono mountains, NY. She said she had to see us all.

She enjoyed the passage because the description of the father-son relationship touched her. Suleiman is quite possessive about his mother; at the same time he is longing for his father’s love and company. The father affectionately calls him Slooma. But the mother still carries a resentment for having been married off so early. The way it was done bothered her.

Zakia showed us the garden in which she was sitting. It had many pretty flowers. A pond with a fountain, trees, wildflowers, birds, chipmunks. The weather was superb.

Zakia joined us from a retreat in the Pocono mountains in New York State, here seen with husband Abbas

KumKum:

Libyan author Husham Matar's book In The Country of Men was nominated for the Booker prize in 2006. The book recounts 9-year-old narrator Suleiman el-Dewani's experiences during the initial part of the Gaddafi regime, while it tried to overpower the pro-democracy forces. The book is a flashback narration of the grown up Suleiman. He described the turmoil in the country in his neighbourhood and its insidious effects within his home and family. Themes of secrecy and betrayal permeated young Suleiman's world.

Martyr’s Square, Tripoli, referred in the novel as being close to Suleiman’s home

Suleiman's father Faraj, was a successful businessman, he was also a member of the pro-democracy group. Often his activities and frequent foreign trips overlapped his personal business, and extended into anti-Gaddafi activities. Young Suleiman was not particularly aware of all this. But he saw how his young mother, Najwa, was breaking down under an inexplicable pressure. She simply could not cope and she became an alcoholic. Her husband Faraj, who was so often absent from home, was no help to her. She sought emotional support from her young son. And she often shared with him her personal stories, including how she was married off to Faraj (Baba) at age 14. Baba was much older to her, and she never emotionally connected with her husband. She felt it was a forced marriage, not an emotionally supportive one.

KumKum chose to read the passage from Chapter 13, where Najwa squarely blamed her America-returned brother Khaled for her being forced to marry Faraj. A simple incident of holding hands with a 14-year-old of the opposite sex in a public place changed her life forever. It was so sad and she remembered it long after. Priya said it is a common thing in India. We can identify with that sadness.

Pamela:

Pamela chose the passage which described the hanging of Ustath Rashid by the revolutionary Committee. It brought back to her memories of the killings during the Hindu-Sikh riots in Delhi in 1984 after the assassination of Indira Gandhi. The angry mood and the callous attitude of the crowds seemed so similar. Pamela remembers a 6-year-old child coming to tell her ‘meine dekha woh log sardar ko jalathe huey’ describing the killing of a Sikh man, witnessed by an approving crowd. The impact was traumatic on children. It would seem there was no empathy for the dying. On the contrary, the crowd was enjoying it! They looked like children enjoying a new toy. The very thought seems revolting! KumKum later mentioned how in their colony the men would take turns at night to walk along the lanes of their colony (Panch Sheel Enclave Block A1) with dandas to ensure the one Sikh family residing there was never hounded.

Execution of Sir Thomas More whose last words were “I pray you, Mr Lieutenant, see me safe up and for my coming down, I can shift for myself”

Later on Suleiman asks pertinent questions - Why didn't someone save Ustath Rashid? Why didn't those who wanted to save him move fast enough? It raises questions about the humanity of watchers of executions right through history. It made Pamela wonder whether the title should have been ‘In the Country of so-called Men.’

Priya opined that the execution was the enactment of Sharia Law, public hanging. Priya doubted the Hindus were happy at the riots. Pamela and KumKum who were there and saw the burning Sikh houses in New Delhi, refuted Priya, telling how Hindus made rabid by the mob mentality were handing out sweets, and clapping. The same goes now in UP when the Hindutva mobs were happy to string up Muslims suspected of eating or keeping beef. People get a sadistic pleasure, said Kavita.

Priya kept insisting it was Sharia Law at work. But Muammar Gaddafi did not bother with any religious sanction to justify his hanging people who stood in the way of his regime; for instance, the dissenter Shaheed Sadiq Shwehdi executed in public in May 1984 in Benghazi – the video is included in the preface.

Devika:

This story is seen through the eyes of a 9-year-old boy, who is terrified by the events around him.

Children have so many fears and we who have gone through this stage in life understand it. A parent coming home later than expected is worrying. Devika’s father was sailing on the Brahmaputra when she was a six-year-old during the India-China war of 1962. To this day she can remember the fear as to when she would see him again.

Life for children during the Gaddafi regime must have been so scary and hellish. Not knowing what will happen in the next minute, especially when Suleiman's father is involved with the opposition pro-democracy party.

Seeing his friend's father being executed on TV, Suleiman must have been constantly worried whether the same fate would befall his father.

Joe said from the reading you can discern the perpetual fear of the young boy when men are carted away, people dressed in black come to interrogate residents, slap them around, pick them up and take them away. Some end up on the scaffolding. The world of the young boy is slipping away, nothing is certain. It’s quite disturbing for a young child as Devika pointed out in her commentary. Joe used to get anxious if his mother was even an hour late in returning from a ‘meeting,’ a word he first heard in the context of sessions his mother used to attend; perhaps they were harmless academic meetings. He never experienced similar panic if his father was late.

KumKum narrated a fear in the household when Joe started wearing a RESTORE FREEDOM badge on his shirt pocket when he was working in IBM and Indira Gandhi declared her infamous emergency. Press freedom was curtailed (Goenka’s Indian Express was in the vanguard of protesting, so was The Statesman), arbitrary carting off of people as enemies of India (remember that slogan ‘Indira is India and India is Indira’?). Joe’s mother would wait anxiously for him to return in the evening.

We hear it nowadays also when the PM identifies himself with India. Joe went around to government customers’ offices and data centres and nobody questioned him for wearing a badge that obviously dissented from the lawless regime of those times. His children it seems somehow feared at home awaiting his return in the evenings, and even more his 82-year-old mother who was staying with them.

Part of the glory of that resistance is how many went to jail, some were tortured, and in the end it was the courage of freedom fighters like Jayaprakash Narayan, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Chandra Shekhar, George Fernandes, lK Advani, Charan Singh, Madhu Dandavate, Morarji Desai, etc. who eventually got democracy back on track in 1977 March. Joe remembers a great Boat Club Lawns speech in which Vajpayee held forth and moved the listeners, vowing they would have their freedoms back. Joe took leave from his office to be present there among the cheering crowd. Vajpayee was a true orator and Nehru admired his Hindi. Nehru introduced Vajpayee to a visiting leader, saying “He (Atal) is a young leader of the opposition who is always criticising me, but I see in him a great future.”

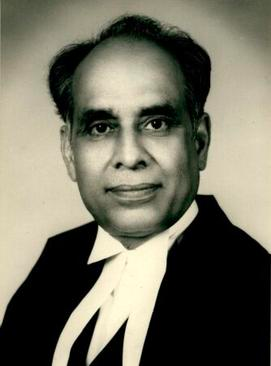

Hans Raj Khanna, attempted to uphold civil liberties during the time of Emergency in India in a lone dissenting judgement in the infamous 1976 case

One should also remember Justice HR Khanna, the sole dissenting judge in ADM, Jabalpur vs Shiv Kant Shukla case (also known as The Habeas Corpus case) in the Supreme Court. The court had to determine whether a citizen had the right to move courts to safeguard his right under Article 21 which reads: “No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.” Would this remain in force when an Emergency is declared? This bedrock of democratic constitutions was being violated. Amazingly, the Attorney General urged the Government’s view that the citizens did NOT have the right to life and personal liberty under the Emergency! The other judges on the bench – Chief Justice AN Ray and Justices MH Beg, YV Chandrachud (father of the present CJI) and P N Bhagawati AGREED; only Justice HR Khanna wrote in dissent – one man of integrity in a court filled with men lacking, not in judicial knowledge, but in spine.

Kavita:

Kavita’s passage concerns the departure of Suleiman (Slooma) for Cairo – he realises he is being sent off and the family will not accompany him. He is leaving behind the two most important people in his life, and may not see his father ever. Suleiman feels very sad that while he may be settled in a comfortable corner of Cairo, his father would not be able to come and visit him, and he himself may not be able to go back. Suleiman senses the sweet sadnesss and finality of the parting. In Cairo he is treated well by Judge Yaseen, the father of his half-Egyptian friend Moosa.

Shoba:

From Tripoli in Libya the story moves to Cairo, Egypt. Suleiman feels the loss acutely when he is left alone in his room by the understanding Judge Yaseen. He cries into his pillow, remembering the scent of his mother. The mother-son relationship runs throughout the book, and that is how the story ends.

Nationalism is a thin line, Suleiman finds, and it no longer inspires him to be fervent about Libya. Pamela confirmed that her two daughters, one settled n USA, and one in Norway, no longer feel for India in the same way. She doesn’t see nationalism in them any more, but perhaps they have adopted a new nationality and will be loyal to that. If you are just living a normal life, nationalism is something in the air, nothing that matters, until demagogues drum it up for political gain (e.g. MAGA or Make America Great Again, Mr Trump’s slogan). Shoba said if you read the book Sapiens, the author says these are stories we tell ourselves and come to believe in.

People living right here in India, who have not gone abroad often do not display any pride in national feeling, said Kavita. Priya noted that her brother in America didn’t want anyone in India a to know when he adopted American citizenship. It made him sad. Joe said when you live in other countries for long, the culture of the place dominates everyday life. America particularly thinks of itself as the whole world, even naming their sports championships as the ‘World Series’, e.g. in Major League Baseball. America has in fact re-colonised the world – they have about 1,000 military bases around the world.

Children of the defence services in India have a larger all-India perspective. Indians abroad may be rightly loyal to their adopted countries but still maintain some roots in India, and a number of desi customs continue abroad. Kavita said Malayalees abroad like to return to Kerala and keep a home here, occupied perhaps only a few months a year, imagining they will some day return, because older folk feel more lonely in USA. But in time that remaining attachment will diminish and it is in vain to think the children of immigrants who were born and grew up abroad will ever come back to settle in India. Tourism perhaps, but not a return.

Kavita related the case of her sister being dragged abroad to meet prospective grooms. She refused to see them and told her parents she only wanted to settle in India. Well-off Indians have little reason to think of going abroad permanently for economic reasons.

But Indians are everywhere in the world. The last tea-shop in the wilderness of the Yukon as you venture north in Canada is an Indian chaiwallah; so too if you are hiking off to Peru on the Inca trail.

The Readings

Joe Ch3 – The History Lesson

Ustath Rashid’s students were wonderfully jubilant; watching them I burned with anticipation to be at university. A couple of girls were pulled up to dance. With eyes downcast they shook their hips and twirled their hands in the air. Passing cars blew their horns. We were like a wedding party.

Kareem and I were sitting in the back, Ustath Rashid in the front, occasionally looking back at us and smiling. When the dancing and the clapping subsided, a chant took hold: al-Doctor, al-Doctor, al-Doctor … We didn’t stop until Ustath Rashid stood up and turned to face us.

‘I am truly honoured to have such an orderly, well-mannered and respectable group of students. I would just like to know where you unruly bunch have hidden them.’

We all laughed, clapping and whistling as loudly as we could.

‘The city of Lepcis Magna was founded by people from Tyre …’

‘LEBANON.’

‘Yes – very good – modern-day Lebanon. Subsequently it became Phoenician, then, of course, Roman, when it was made famous by its loyal son, Emperor Sep …’

‘SEPTIMIUS SEVERUS.’

‘Yes, our Grim African, both a source of pride and shame.’

‘PRIDE PRIDE.’

‘Well, if you insist.’

Then the bus turned down a dirt road that led to the sea.

‘Welcome to Lepcis,’ Ustath Rashid announced. He seemed transformed. Stepping down from the bus, smiling at the abandoned city scattered by the lapping lapping sea, its twisted columns like heavy sleeping giants by the shore, he gave a deep sigh and recited a poem:

Why this emptiness after joy?

Why this ending after glory?

Why this nothingness where once was a city?

Who will answer? Only the wind

Which steals the chantings of priests

And scatters the souls once gathered.

Some of his students clapped. He smiled, bowed, blushing.

‘Sidi Mahrez’s lamentation for Carthage could have equally applied to Lepcis,’ he said marching ahead.

We all struggled to keep up.

He took us to see a broken frieze that displayed part of the Emperor’s name. Absence was everywhere. Arches stood without the walls and roofs of the shops they had once belonged to and seemed, in the empty square under the open sky, like old men trying to remember where they were going. Coiled ivy and clusters of grapes were carved into their stone. White-stone-cobbled streets – some heading towards the sea, others into the surrounding green desert – marched bravely into the rising sand that erased them. Ferns, grass and wild sage shot through the stone-paved floor. Palm trees bowed like old gossiping women at the edges of the city.

He showed us the ‘Medusa medallions’ carved in marble and inset high between the leap and dive of the limestone arches. They were boys with healthy cheeks full as moons, encircled with lush curls, their foreheads flexed, eyes anxiously inspecting the distance, lips gently open. ‘They are also known as the “Sea-monsters”,’ Ustath Rashid said, ‘always facing the sea, always expecting the worst.’

Kareem continued staring up at the Medusa medallions long after the group had wandered off to the next object. ‘What’s the point?’ he said. ‘To scare away the enemy,’ I said. ‘And how do you expect them to do that?’ ‘I don’t know,’ I said and walked away. ‘Children are useless in a war,’ he said following me.

We caught up with Ustath Rashid in what were the baths, tiled rectangular cubes carved into the ground and under domed roofs. Flaked frescoes of men stabbing spears into the necks of lions and cheetahs, others on boats in a river full of yawning fish, lined the walls and ceilings. Ustath Rashid stopped in front of a painting of a naked woman.

‘This is a Maenad, a follower of the cult of Dionysus, the god that alleviates inhibitions and inspires creativity.’

Her eyes were as strange as a bird’s, her lips full and melancholy, the area around her nipples glowed pink, and her stomach stretched down to hips that widened out softly. … I turned my finger round the pink centre of her nipple. Then my eyes fell on her dark lips. I kissed them, hearing my own breath against the cool dry stone. Something like guilt or fear made me withdraw.

Saras Ch 8 – Najwa Defends Her Family

‘You are children playing with fire. How many times I told him: “Walk by the wall, feed your family, stay home, let them alone, look the other way, this is their time not ours, work hard and get us out of here, let me see the clouds above my country, Faraj, I want to look down and see it a distant map, reduced to lines, reduced to an idea. For your son’s sake. In five years he’ll be fourteen, they’ll make a soldier out of him, send him to Chad.” How many times I repeated it! “Five years!” he would mock. “In five years everything will be different.” Now look where his recklessness has led us.’

‘Bu Suleiman is an honourable man who wants a better Libya for you and for Suleiman.’

‘And who does he think he is to want that,’ Mama yelled back. Her voice was strained, it made it impossible to argue with her. ‘They are mighty. He thinks he alone can beat them?’

‘He’s not alone.’

‘Oh, my apology, I forgot about the handful of men with nothing better to do but hide together in a flat on Martyrs’ Square and write pamphlets criticizing the regime. Why hasn’t anybody thought of that, I wonder? Of course, that was the answer all along; how foolish of me. Look now where it has led you. A massacre is in the making. God knows if Rashid will make it, the poor man, stupid enough to believe your dreams.’

‘They are his dreams too. Have hope, strengthen your heart.’

‘Don’t patronize me. You are all fools, including Rashid and Faraj. But no, I must be a good wife, loyal and unquestioning, support my man regardless. I’ll support nothing that puts my son in danger. Faraj can fly after his dreams all he wants, but not me, I won’t follow. I will get my son out of this place if it takes the last of me.’

Mama seemed to have boundless anger; all it needed was a word, a gesture, to come lashing out. Moosa seemed to know this; he kept his eyes on the table. She paced the room. ‘Inflating his chest,’ she said under her breath, then louder,

‘Inflating his chest,’ as if the first time was a thought, a rehearsal of what was to come. ‘Yes, that’s what you do when you sit at his feet, reading and re-reading to him the newspaper articles that you know kindle the fire in his heart, urging him on, pushing – always pushing – and if the printed words weren’t hot enough you would add in your own bits, because you need a hero, you need someone to pluck you out of your own failures, a pair of strong hands always there to rescue you and send you to places you don’t belong, to be something, to prove to your good father that in the end you were right to go against his will, that unlike everyone else you don’t need a university degree because you were destined for greatness, riding the wave, clutching the coat-tails of history, while all along you knew that the man you chose to lead you was no hero, but an ordinary man, a family man, inflating his chest, making him think he had powers he didn’t have, that he could face the volcano, and you – what did you do? – beating the drum that urged him on, nudging him forward, forward.’

Priya Ch 9 – Cruelty Among Children even as They Play

‘Do you want to play My Land, Your Land?’ he said.

This was the first time in a week, since his father had been taken, that Kareem had wanted to play. So although I wasn’t in the mood I took his blade and drew as wide a circle as I could round myself. My shadow was directly beneath me, it was noon. I divided the circle into two equal halves, his land and my land, and gave him the knife handle first. He was still observing my drawing, and even though his face was serious it was approving. We stood outside the circle and began. My Land, Your Land was our favourite game; Kareem and I played it often because all it required was two players, a good blade and the dirt beneath us.

Kareem was good at most games and it was always easy losing to him, not only because he was older but more because he would never show that he enjoyed his victory. In fact, on winning, a look of regret often cast itself on his face. Although I was much younger than Kareem, he always treated me as an equal. Even if there was always the acknowledgement on my part of the three years that separated us: I sought his advice, and when there was a dispute between him and any of the other boys I always took his side.

His first throw was bad, the knife fell flat on its side. Mine was good, the blade left a clear mark on Kareem’s half of the circle that meant most of his land had become mine. That determined the first game, and luck stayed with me for the next two. I beat Kareem three games in a row. This had never happened before. Never before had I been so confident in my throws; before the knife left my hand I was certain of success. The tightness in my throat had eased and tears were the furthest thing from my mind.

Osama, Masoud and Ali joined us. ‘You let a boy beat you?’ Masoud said. This was made worse because Ali usually repeated what his brother said. ‘You let a boy beat you,’ he echoed. Then Osama too teased him, saying, ‘Serves you right for befriending a child.’

‘I am not a child.’

‘Of course you are,’ Kareem said, with an irritation that made the betrayal harsher. ‘He seemed grumpy, so I let him win,’ he told them.

‘You’re a liar,’ I heard myself say. ‘Who are you calling a liar?’

‘Losing three games in a row is shameful, but to lie about it and say you let me win, well, that’s just not right. No surprise there, I suppose,’ I said, feeling a dark, unstoppable force gain momentum.

‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘Come on, Kareem,’ I said, looking at the boys and letting a smile escape me. ‘Everybody knows about your father.’

‘What about my father?’ he demanded, taking a step towards me.

I studied my fingers. ‘People are talking.’ If I could have pulled those words back I would have, but they were out and I had committed myself.

‘And what are they saying?’ he said through gritted teeth. His narrowed eyes fixed on me, they were impossible to ignore.

‘Everybody knows your father is a tr—’

Kareem leaped on me. His weight threw me to the ground. He didn’t punch, we didn’t roll on the ground, he just kept squeezing his arms round me. I remember thinking: what if I wasn’t going to say ‘traitor’, Kareem; what if I was going to say another word that started with the same two letters? You would have leaped on your friend for nothing then. Osama pulled him off me. Kareem’s face was so red he might have been crying. Only a few minutes before it was I who had feared crying in front of him. Masoud pulled me up and dusted my back, slapping it a little too hard. I thought, perhaps in his house, with his fat and certain mother, his powerful and well-connected father, such firmness was always necessary. I noticed then that in one hand Kareem was clutching the knife. He could have stabbed me. He still loves me, I thought. We are still friends.

Arundhaty Ch 12 – The Mokhabarat Police try to Soften up Suleiman

‘Did you hang up on him like I told you to?’

‘Yes.’

‘Good boy. Now listen, there isn’t much time, I need you to give a message to your mother.’ He was still whispering. I didn’t like him calling me ‘Good boy’ but I had never felt such affection for Nasser as I did now. ‘Tell her that we are doing all we can to find Ustath Faraj, we don’t know where he is, he hasn’t turned up here.’ I imagined him speaking from the flat on Martyrs’ Square. ‘We have been expecting him … do you know where he is?’

‘Why don’t you stuff this telephone up your arse, fucker,’ the voice returned again.

‘Hang up, Suleiman,’ Nasser shouted, and this time I hung up immediately. But as soon as I did, the telephone rang in an odd continuous ring. Fearing it would disturb Mama, I picked it up. It was the same man. His voice was clear, the echo now gone. ‘Listen, boy. Do you know Nasser’s family name?’ I said nothing, but then he shouted, ‘Speak up.’

‘No,’ I said, remembering Ustath Rashid’s interrogation on television.

‘Do you know where he lives?’

‘No.’ Then, fearing what he might say next, I said, ‘Yes.’

‘Good,’ the man said and I thought it was over, but then he said, ‘Look, Suleiman, this is how this works. You will tell me where Nasser lives, and I will write it down. OK?’ I felt my head nod, then, as if he could see me, he said, ‘OK.’

After a short silence he shouted, ‘Speak, boy.’

‘You know where Martyrs’ Square is?’

‘Yes,’ he said so softly it astonished me.

‘He lives in one of the buildings there.’ Then in a lame attempt at retreating I said, ‘I think. I am not sure.’

‘But of course you are … sure,’ he said with confidence. I was confused. The pause before the word ‘sure’ seemed so deliberate I wondered whether he meant of course I was not sure, or of course I was sure. ‘And which building on Martyrs’ Square are you not sure he lives in?’ he said.

‘The one right on the square.’ His silence was heavy, so empty I felt I had to say more. ‘It has green shutters. His is on the top floor, with a red towel on the clothesline in front of the window.’

‘Good,’ the man said. Then he added, and again I didn’t know whether he was speaking to me or to someone else beside him or even to himself, ‘The red towel, that’s the code, the bastards.’

‘Nasser is a very nice person,’ I added. But he had hung up.

Zakia Ch 13 – The Mother-Son Relationship and Baba

The window in my room was open. From where I lay I could see the sky blue and solid above the white garden wall made golden by the sun, the line where they met red and black, a trick of the light. Staring into the sky often made me thirsty; now it was causing a place in my chest to tickle. I wondered how it would be to fly, to be inside the solid blue. One day Baba will take me with him on a business trip, I was certain. I will dress in a suit and tie and walk beside him like a shadow, his ‘right hand’. When we board the plane I won’t be impressed because flying will be normal to me by then. We will sit and not even look out of the window, busy with more important matters written in long slim columns in newspapers. I will then be a man, heavy with the world. I imagined my life without Baba, I imagined doing all of these things alone, and the tickling in my chest stopped. I hardly ever did something alone with Baba, and to give up this one fantasy saddened me. He was away so often, and when home he was usually distracted by a book or a newspaper. I was perplexed whenever I caught him looking at me with longing.

The only activity Baba and I did alone was the walk together to the mosque on Fridays. Although Mama never herself prayed or insisted that I did, she was still proud to see me dressed in my white jallabia and cap, holding Baba’s hand, musked and ready for prayer: a miniature replica of Baba. I didn’t look forward to Friday prayer and was always happy when it was over, but I did like the walk with him. I remember holding his hand and squinting against the bright noon sun, our white jallabias glowing in the heat. He was always silent during these walks, no doubt refraining from speech in order to listen to the Quran as it blared off the minaret speaker, recited by Sheikh Mustafa, too loud to be understood. Many times during the prayer I remained standing while all the worshipers bowed. Watching the entire place change colour, I felt frightened to be the only one in the world seeing them like this: a carpet of hunched white backs like seagulls grooming their chests. After the prayer Baba enjoyed introducing me to his friends. They thought it sweet that I was dressed like him. I never went to prayer when Baba was away.

When he was home, Baba seemed distant. Away he seemed closer somehow, more alive in my thoughts. For this reason it was strange when Mama merged us together. She did this by using the plural form of ‘you’. ‘You always leave me alone,’ she would say, after I’d come in from playing in the street, meaning both of us, using the you that made Baba and me inseparable. It obliged me to defend him, to say, ‘But Baba is working hard for us,’ when I had no idea whether he was working hard for us or not. I defended him because I was defending myself. But I know now that that, of course, made us indistinguishable, the man who was her punishment and the boy that sealed her fate.

KumKum Ch 13

Mama blamed Uncle Khaled for that black day she was forced to marry Baba because of what he had done when, on one of his visits from America, he saw her and her friend Jihan in the Italian Coffee House drinking cappuccino with two boys. Mama and Jihan were fourteen years old, as were the two boys.

‘The coward. Thinking himself the enlightened American. He was nice. Cordial. Said hello as if he admired his little sister and her friend. The foolish girl I was; I even thought, with his liberal ideas, he was proud of my little rebellion. He paid for our cappuccinos, said hello to my friends. When he left I cried with happiness and told Jihan how much I loved my brother. Having a brother like him was the only thing in my life that in any way resembled Jihan’s life.’ Jihan was Mama’s childhood friend, a Christian from Palestine. Her parents treated her the same as they did her brothers. ‘Talk about a rude awakening. When I got home every light in my life was put out. The High Council was already adjourned. Oh yes, when it comes to a woman’s virtue we are fierce. Fierce and deadly. And when it comes to a daughter’s virtue we are fierce, deadly and efficient. In such matters our efficiency rivals that of a German factory.’ A smile crossed her face and was gone. ‘Your grandmother grabbed me by the hair and threw me in my room. “You have shamed me, you little slut. Now your father will think I haven’t brought you up right.” I didn’t know what she was talking about. It was like a nightmare, no sense in it at all. But soon I learned that the poet-prince had run straight home after seeing me at the café and told his father, “Your daughter is fourteen and is already spending her days in cafés with strange men. I tremble to imagine what next. Marry her now, or she’ll shame us all.”

Pamela Ch 17 The Hanging

The crowd was jumping now, jumping and howling, Hang the traitor! Hang the traitor! When the men stood him below the rope he tried to kiss one of their hands again. His lips were now as thin as liquorice sticks when pulled at either end. Someone behind him was motioning eagerly for assistance, then a ladder appeared. It was a wide, sturdy-looking aluminium ladder. It shone under the bright lights. It looked brand-new, feathers of ripped plastic stuck out round its feet. Ustath Rashid was made to climb it. At every rung he stopped and begged for mercy. He was pushed along with a strange tenderness, with a mere nudge to his elbow. But after a couple of times the man nudging him seemed to reach the end of his patience. He climbed up beside him and pulled him up by the arm. Ustath Rashid was now halfway up. The rope brushed against his face, making him blink. The man placed the rope round Ustath Rashid’s neck and tightened it. Then he slapped the air beside his ear as if to say, ‘There, done,’ or, ‘See how easy?’ and climbed down. Ustath Rashid’s body sagged a little.

‘He’s fainting,’ Moosa said, in the same slow, elongated way in which he had been offering his commentary throughout.

Mama said nothing.

Moosa was right. Ustath Rashid slipped off the ladder and was snatched by the rope. This caused an uproar; the crowd was ready. He was propped up, slapped a couple of times across the face, then turned towards the camera. We could see now that his trousers were wet. Something yellow appeared from his mouth and seemed to grow. No one wiped it off, no one brought him a glass of water, a toothbrush and toothpaste to wash away the burning and greedy acid. His head didn’t shake in disgust, he seemed to be oddly comfortable with his vomit.

The camera turned to the spectators. They were punching the air and cheering. Several women ululated. And suddenly, like a wave rising, the cheering became louder and more furious. The camera swung quickly, and we saw Ustath Rashid swinging from the rope, the shiny aluminium ladder a metre or two to one side, too far for his swimming legs. The crowd spilled down on to the court now. Some of the spectators threw their shoes at Ustath Rashid, a couple of men hugged and dangled from his ankles, then waved to others to come and do the same. They looked like children satisfied with a swing they had just made. Everybody seemed happy.

Devika Ch 18 – Children Feeling Panic When Their Parents Get Delayed

How could it be so easy? What was absent in the Stadium? What didn’t intervene to rescue Ustath Rashid? Perhaps it was all the cowboy films with their logic of happy endings that made me think this way, that perhaps it wasn’t God but they who had invented hope and the promise that just at the point when the hero had the rope round his neck, suddenly, and with the Majesty of God, a shot would come from nowhere and break the rope. The hero would kick the man beside him, and the rest of the mob – the cowards – would jump on their saddles and ride off, up and over the hill. Everyone at the cinema would jump and shout and clap and hug one another as if it were a football match. Tears would come down my face, but it wouldn’t matter because many cheeks, grown men too, would shine with tears. I recalled the joy of such moments and how they seemed to burn a hole through my chest. Where were the heroes, the bullets, the scurrying mob, the happy endings that used to send us out of the dark cinema halls rosy-cheeked with joy, slapping each other’s backs, rejoicing that our man had won, that God was with him, that God didn’t leave him alone in his hour of need, that the world worked in the ways we expected it to work and didn’t falter? Something was absent in the Stadium, something that could no longer be relied on. Apart from making me lose trust in the assumption that ‘good things happen to good people,’ the televised execution of Ustath Rashid would leave another, more lasting impression on me, one that has survived well into my manhood, a kind of quiet panic, as if at any moment the rug could be pulled from beneath my feet. After Ustath Rashid’s death I had no illusions that I or Baba or Mama were immune from being burned by the madness that overtook the National Basketball Stadium.

Kavita Ch 23 – Suleiman leaves for Cairo

The airport was empty. I felt as nervous as I had on the first day of school. Orange plastic chairs lined up in rows like boy scouts across the dark marbled floor. I only noticed she didn’t have a bag with her when Baba was lifting my heavy suitcase on to the check-in conveyor belt and I remembered that she had said, ‘You are going on a trip.’ ‘You’, not ‘we’. I told myself off for not noticing this detail before, before when I could have clung to the door frame, the garden gate, could have run to the sea.

Baba was now busy talking to a woman dressed in a uniform. She had a brooch in the form of a wing fastened to her lapel. He pointed his finger at her, then placed money in her hand. She nodded, touched him on the arm and walked away, smiling the whole time. Then he dug his hands under my arms and lifted me into his embrace.

‘We will come and see you,’ he said, squeezing me too tightly.

Mama, standing behind him, had one hand over her mouth, her eyes concealed behind the black sunglasses. ‘You’ll be home soon,’ she said, nodding as if to reassure herself.

‘Please don’t cry, Slooma,’ Baba said.

Then I was taken by the stewardess, who seemed to know everything. I looked back and saw Mama in Baba’s arms. There they were, the two people I loved the most, the two people I was certain would do anything to keep the truth from me, huddled together in the empty airport, disappearing. Is this the time to wave? But I could no longer see them. In every direction I turned they weren’t there.

The truth couldn’t be kept away, it was cunning, sly-natured, seeping through at its own indifferent pace, only astonishing in how familiar, how known it has always been. I had known I was going to be sent alone to Cairo, that the name of the school she had written down, telephone receiver held between ear and shoulder, was of my future school, knew it before I noticed she had not brought a bag to the airport, knew it when I cried, ‘I don’t want to leave, I don’t want to see the Pyramids,’ into Baba’s belly while Mama was buying the sesame sticks meant to sweeten my mouth, cover the bitter taste, cheat me out of my grief. I knew it and didn’t run to the sea. And when I was finally brought to my seat inside the aeroplane, the aeroplane I had up to that moment fantasized about entering with my father, both men, both dressed in suits, busy with the world, heavy as all men are, I knew that I would never see my father again, that he would die while I was installed alone in a foreign country to thrive away from the madness.

Shoba Ch 23 – Suleiman’s new life in Cairo.

I had integrated rather smoothly into my new Egyptian existence. My young age and the judge helped make this possible. His wide circle of friends and associates became mine, and those old moist-lipped Egyptian judges that used to meet on his balcony in Tripoli, all those years ago, close to our house, in the neighbourhood the judge liked to call Gorgi Populi, regarded me with particular affection. Doors, in a country full of closed doors, opened effortlessly, easing my progress and my definition of myself.

What was astonishing is how free I came to feel from Libya. If one of my friends teased me about my ‘Bedouin origins’ or about our ineffective football team, I smiled only to please them, but truly felt nothing, none of the fervour that had once caused me to cry, after six hours of watching a chess match in which a Libyan had lost to a Korean at the International Chess Championship in Moscow. Nationalism is as thin as a thread, perhaps that’s why many feel it must be anxiously guarded. I neither sought nor avoided the Libyans who lived in Cairo. This even when I knew that the embassy had a file on me. I was down as an ‘Evader’ because I had not returned for military service. Then, when I became too old to be militarized but was still too young to be forgiven, another decree meant that if I were to return I would serve the same period in prison. And like all Libyans who don’t return, the shadow of suspicion fell firmly on me, strengthened further by yet another decree, issued when I was fourteen, promising that all ‘Stray Dogs’ who refused to return would be hunted down. These decrees got ever more desperate. The government’s next move was to refuse my parents a visa to leave the country, holding them hostage, as it were, until the evading Stray Dog returned.

Why does our country long for us so savagely? What could we possibly give her that hasn’t already been taken?

I yearned for them, my room, my workshop on the roof, the sea, Kareem. What I missed most was the smell of our house. Once, but only once, when I was still a boy, I cried and screamed, throwing things as I had done before to stop Baba going on one of his endless business trips. Judge Yaseen reacted nobly. He simply shut the door to the room that he had given me in his house, then later sent the maidservant in with a cold glass of sugarcane juice. I buried my face into the sharp lavender smell of the pillow, mourning the familiar: digging my face into her neck, kissing his hand.

Wonderful read dear Joe. We truly missed a good session. As usual the book unfolds a crucial political situation and it's aftermath. The historic details are very interesting indeed which you brought alive with pictures. Read through each one's contribution and vicariously enjoyed being part of it. Thanks Arun and Pam for a good selection of book.

ReplyDeleteThank You dear Joe, for a wonderful job you did in putting together a beautiful blog post of KRG's May session. Especially I liked the introduction you wrote to the blog. I found a new word there, a noun, I did not meet before "Bildungsroman", which means a novel dealing with one person's formative years of spiritual education.

ReplyDeleteI also enjoyed reading your paraphrase of our entire session that day. How patiently and laboriously you did that job listening to the voice records by Zoom.

Once again an excellent compilation of our reading session. Thank You Joe, you value add so much more to what is presented at the session.

ReplyDelete