Pamela, Geetha, Devika, Saras

This

poetry session was announced as a year-end occasion to recite ‘happy’

poems. Readers therefore chose humorous poems for the most part; or

poems exhibiting the lightheartedness of major poets who have shed

their seriousness on occasion.

Saras, Hemjit, Shoba

It

was a time to dress for the coming holiday season in gay clothes.

Thommo was sure he would stand out as the most gaily dressed with his

fancy blue silk shirt with coloured squares, but he didn’t reckon with the bold yellow, red, and black

printed shirt Joe wore (of

Thai origin, presented by his

daughter, although it looked gorgeously African); and a turban wrapped

with

KumKum’s dupatta!

KumKum, Priya, Thommo

The

women were colourfully dressed too, many in red for the season.

Unfortunately, Priya arrived with such a bad case of voice lost, that

she excused herself after wishing us in sign language, and left to

recuperate from her pharyngeal stifle.

Pamela, Geetha, Devika

It

was also an occasion to

celebrate at year-end for

having read six wonderful novels and a hundred or more moving poems

through

the year. Thommo arranged a dinner in the

dining hall of the Yacht Club

for readers and their

partners – but no partners, other than reading members,

could attend.

Butter chicken, matar

paneer,

kadai mixed vegetable, and

salad, followed by mango cheesecake was on the menu, with plenty of

tandoori parathas and rotis.

Kavita, Pamela, Geetha, Devika, Saras

Joe and Kavita

We

came up with the

final list of six novels for next year and included an extra

month to read short stories; this

time, stories of the Pakistani

author, Saadat-Hasan

Manto translated from Urdu.

That means we will have just five Poetry sessions

in 2019.

Pamela & Geetha

At

the end KumKum and Shoba pronounced it was a lovely

session and here we are in a radiant

group:

(standing) Joe, Kavita, Devika, Shoba, Zakia, Geetha, Pamela, Thommo (sitting) Saras, Hemjit, KumKum

Full

Account and Record of the Poetry Session on Happy Poems Dec 7, 2018

A

few readers had expressed a desire earlier to read short stories,

specifically the volume titled Manto:

Selected

Short Stories, translated by Aatish Taseer. Saadat-Hasan

Manto was the Urdu writer who migrated to Pakistan after

Independence. Instead of Poetry in Feb 2019 we will read and discuss

the ten (some say, twelve) short stories in this volume. The list of six novels for reading in 2019 was also finalised.

Manto - Selected Short Stories

Present:

Joe, Kavita, Pamela, Saras,Geetha, Devika, Hemjit, Shoba, KumKum,

Zakia, Thommo

Virtually

Present: Gopa

Absent:

Sunil, Preeti, Priya (sick, but came to say hello)

Gopa

She

introduced the short poems of Spike Milligan (1918 – 2002) with an

introduction to his life. “Patrick Sean Milligan, known as Spike

Milligan, was the Indian-born, British-Irish comedian, actor, and

playwright. He was best known for his radio program, the Goon

Show. Some of the best British comics were his contemporaries and

collaborators from the 1950s to the 1980s — Jimmy Grafton, Eric

Sykes, Larry Stevens, Peter Sellers, and John Cleese of Monty Python

fame. He was also a novelist, author of Puckoon (1963) which

has been selected for reading at KRG this year in May by Priya &

Thommo. Milligan wrote what is known as ‘literary nonsense’,

though not everything he wrote was nonsensical. He suffered from

depression at times in his life, and what he wrote in those periods

were not of the Edward Lear or Ogden Nash type.

Spike Milligan (1918 - 2002) will be remembered for the Goon Show

I

selected some of his comic poems, including On the Ning, Nang,

Nong, perhaps his best known; even today it is one of the top ten

verses taught in primary schools in the UK.”

You

can read more about Milligan and his fond memories of India at:

Once

when Spike Milligan appeared in Scottish kilt and tartan, he was

asked “Is anything worn under the kilt?” He replied, “No, it’s

all in perfect working order.”

Joe

Joe

introduced the author of the poem The Canticle of the Sun in

these words:

“Saint

Francis, known as Il Poverello, the poor one, lived from 1181

to 1224 in the Umbria region in central Italy about 180 km north of

Rome. Even today it is a picturesque region, hilly, with fields of

wheat, olive trees, oranges and figs. The poem I am going to read was

written late in the life of Saint Francis as verses of of praise to

nature, which were to be sung by the friars of his order to the

greater glory of God. He added some verses toward the end on peace

because the region was involved in hostilities which he wished to

stop, and the final verse concerning death was added near the end of

his life. It is interesting as literature because it is perhaps the

oldest surviving document in Italian, written in the Umbrian dialect,

at a time when it still retained a lot of Latin forms and words.

Saint Francis - Fresco by Cimabue, (detail from Madonna in Majesty with the Child, Angels, and St. Francis), 1278-80, Basilica di San Francesco, Assisi

Joe

read the poem in the original and allowed the readers to follow the

parallel English, side by side. He said the verse on Water affected

him most:

Praised

be You, my Lord, through Sister Water,

which

is very useful and humble and precious and chaste.

Joe narrating Saint Francis’ life, photo courtesy Zakia

The

wonderful choice of the four adjectives makes clear the precious

nature of this gift, and impresses on us that water comes with such

qualities, and it is we who make it foul and impure. It is we too who

waste the resource in thoughtless ways, leaving others lacking.

That

he praises death (“our Sister Bodily Death”) in the final verse

is a koan that asks for an understanding. Perhaps the saint was

living with death all the while, and seeing it as the final threshold

that had to be crossed, willingly, to realise true joy. Shall we will

our death when the time comes?

Francis

or Francesco as he was known (the little Frenchman, nickname given by his father) was born as

Giovanni Bernardone, to Lady Pica of French Provençal origin, and

Pietro Bernardone a prosperous cloth merchant of Assisi. He was a

happy and carefree young man with lots of friends and even some

military ambitions. At some point he became dissatisfied with his

life, and grew serious, and perhaps heard an inner voice. He would go

off to the ruined hillside church of San Damiano and meditate. As he

grew distant from friends he thought he heard a voice calling from

the crucifix to repair the church; which he duly did, borrowing money

and spending some of his father’s and putting in the manual labour

and soliciting help. But the voice was not satisfied, and he

understood that it was not a physical church he was being asked to

rebuild; it was the life of the church itself that needed

reformation.

When

it came to framing the rules of his order, called the Friars Minor,

he took three cardinal passages from the Gospel.

1.

To hand over wealth to the poor. (Mark 10:21)

2.

To share the good news with others, but to take no money or spare

clothing for the journey (Luke 9:3)

3.

To leave everything and follow Jesus first. (Matthew 16:24)

His

life was occupied in inspiring his friars to care for the sick, even

lepers, and by his example he showed the joy that could be lived in a

life so spent. Saint Francis was an inveterate traveller and went on

missions to far-off places including a visit to the Sultan in Egypt

in order to put a stop to the warfare of the Crusades and to preach

to him.

Francis, Scenes from the Life of the Saint - Stigmatisation of Saint Francis, 1325, fresco, Bardi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence

He

became blind, and suffered ailments, and at one point he was

lacerated with the stigmata, the wounds of Christ on the cross. He is

known as the Patron Saint of Ecologists for the great love he had for

nature, and his readiness to talk to creatures as if they were his

own brothers and sisters. This poem is an example.

Saint Francis in Ecstasy, painting by Giovanni Bellini

I must add that no

Pope before the present one dared to assume the name Francis, for it

means that he has taken a special observance of the Saint’s unique

charisma as something to imitate. Nobody can imitate Francesco, but

he is the most universally loved of all saints. A final footnote: the

second encyclical letter of the Pope Francis I was on Care for Our

Common Home the Earth, and he took the title from

this poem, Laudato Si’, Praise be to You.

COP21 Paris – Pope Francis I donated a pair of shoes to stand in the Place de la Republic standing in for a protest that was banned by police

Kavita

mentioned that Pope Francis decided not to occupy the top floor of

the Vatican's Apostolic Palace, and instead resides in a two-room

apartment in a communal building, living with other priests in the

Domus Santa Marta. Thommo noted the hymn All

Creatures of Our God and King,

authored by Saint Francis, is

based on this poem.

Kavita

Kavita

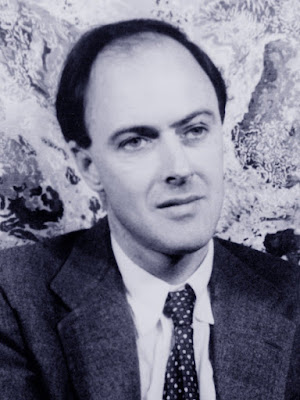

read a poem by Roald Dahl, called Television.

The important message is contained

in the first six lines:

The

most important thing we've learned,

So

far as children are concerned,

Is

never, NEVER, NEVER let

Them

near your television set –

Or

better still, just don't install

The

idiotic thing at all.

Roald Dahl, British writer and poet

For

good measure Dahl enumerates the disease that overtakes TV besotted

children:

HIS

BRAIN BECOMES AS SOFT AS CHEESE!

HIS

POWERS OF THINKING RUST AND FREEZE!

HE

CANNOT THINK – HE ONLY SEES!

Throw

away the TV, and instead fill the house with books and then the

miracle will happen:

They'll

now begin to feel the need

Of

having something to read.

And

once they start – oh boy, oh boy!

You

watch the slowly growing joy

That

fills their hearts. They'll grow so keen

They'll

wonder what they'd ever seen

In

that ridiculous machine,

When

the poem ended there was a rousing ovation for the lines. Naturally,

for we’re

a Reading

Group.

Kavita mentioned

that she has caught herself busily

thumbing through WhatsApp

messages while in the company of her children. Now she puts down her

mobile right away.

Roald

Dahl (1916 – 1990) was born to Norwegian parents in Llandaff,

Wales. He was one of six children raised by his single mother

following the death of both his father and a sister when he was

three. After school he went on a journey to Newfoundland with an

Exploring Society, and then briefly worked for Shell Oil in Dar es

Salaam. He joined the Royal Air Force in Nairobi when WWII started

and survived a crash landing in the Libyan desert. After recovering

from his injuries in Alexandria he returned to action, taking part in

battles and becoming an ace fighter pilot. Later, after a posting to

Washington, he supplied intelligence to MI6.

After

the war he began writing for children while raising five himself with

his first wife, American actress, Patricia Neal, whom he married in

1953. They divorced after 30 years, and he later married Felicity

Crosland. His daughter Olivia died of measles at age seven, and his

infant son, Theo, sustained brain damage in a car accident. After the

accident, Dahl combined with

a toymaker and a neurosurgeon to

invent the Wade-Dahl-Till

(WDT) shunt, which was used to treat thousands of children by

draining excess fluid accumulation in the brain.

Dahl

began his writing career with fiction and nonfiction for adults. He

published nine short story collections, including Over

to You (1946); two

novels, Sometime Never (1949)

and My Uncle Oswald (1979);

and several screenplays for films, such as Chitty

Chitty Bang Bang and the

James Bond film You Only Live Twice.

Dahl was awarded the Mystery Writers of America’s Edgar Award three

times.

His

19 books for children include some famous ones such as James

and the Giant Peach

(1961), Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964),

and the Whitbread Award-winner The Witches (1983),

and Matilda (1988),

which won the Children’s Book Award.

He

wrote two memoirs, Boy (1984)

and Going Solo (1986),

and is the subject of the biographies Roald Dahl: A

Biography (1994), by Jeremy

Treglown, and Storyteller: The Authorized Biography of

Roald Dahl, by Donald

Sturrock (2010).

Roald Dahl, middle aged and balding

The

Roald Dahl Foundation and Roald

Dahl’s Marvellous Children’s Charity, established by his

second wife, Felicity Dahl, offer grants in the areas of neurology

and hematology. The Roald

Dahl Museum and Story Centre is located in Buckinghamshire,

England, where Dahl spent most of his adult life. Dahl died in 1990

at a hospital in Oxford of a rare blood disorder. He was 74.

Pamela

Pamela

was going to read The Tale Of Custard The Dragon

by Ogden Nash. It is anthologised in many books of poems for

children. The poem invites

the reading parent to enact the whole

menagerie of characters. It tells the

story of a girl Belinda and her four pets with these names:

Kitten

– Ink

Mouse

– Blink

Dog

– Mustard

Dragon

– Custard

The

first three were brave, the fourth was a funk of a dragon! The rhyme

pattern is aabb and

provides a galloping rhythm for children to rejoice in.

Pamela

felt there was too little available on Ogden Nash, but search and you

will find, as Google says. Ogden Nash was a whimsical

American dabbler in light verse, who left Americans in stitches with

his verse, often two- or four-liners, but sometimes extending to long

storied verse, like the tale of the dragon, recited by Pamela.

Ogden Nash - The Golden Trashery of Ogden Nashery cover

His

best known collection is sub-titled The Golden Trashery of

Ogden Nashery; the

title was undoubtedly chosen

by him. In his verse Nash combined puns with elaborate rhymes and

sometimes extended lines that ended in a resounding crash of

unexpected rhyme; one could

not but admire the wit.

Ogden Nash

Ogden

Nash was born in Rye, New York. His father had a

business in Savannah,

Georgia, which required him

to spend time in New York.

This

meant Nash’s

formation was a composite of the relaxed

South and the cosmopolitan

East. Nash attended Harvard briefly and then dropped out because his

family couldn’t afford to keep him there.

He

worked for a while in a school and then went to work

on Wall Street. He

failed but moved on and took

a job in advertising, creating slogans to be

splashed on New York’s tram cars. From there he got

a job in the advertising

department of Doubleday, the publishers. Nash demonstrated

he had an aptitude for catchy

slogan-writing.

He

tried to write serious poetry. Of that attempt he later recalled:

“I wrote sonnets about beauty and truth, eternity, poignant pain.

That was what the poets

I read wrote about, too — Keats, Shelley, Byron, …”

Later

he decided he had better “laugh at myself before anyone laughed at

me,” and confined himself to what he has become famous for. Louis

Untermeyer, the critic who wrote the foreword to the Golden

Trashery remarked that Nash’s

poetry was “interesting to brows of all altitudes.”

Nash

collaborated with Christopher Morley, the poet and essayist, and

found his voice when he began

composing humorous pieces.

The

first was this, placed

in the New Yorker published in the Jan 11, 1930 issue about

a senator named Smoot from the state of Utah (Ut. For short):

INVOCATION

(Smoot

Plans Tariff Ban On Improper Books — News Item)

Senator

Smoot (Republican, Ut.)

Is

planning a ban on smut.

Oh

rooti-ti-toot for Smoot Of Ut.

And

his reverend occiput.

Smite,

Smoot, smite for Ut.,

Grit

your molars and do your dut.,

Gird

up your l--ns,

Smite

h-p and th-gh,

we'll

all be Kansas

By

and by.

Nash’s

serious business was to amuse his readers. He was not afraid to

mutilate words

and join them in unforeseen

ways to achieve his aim of sudden revelation in a startling rhyme.

Nash

soon had a second poem accepted

by the New Yorker, and

quickly gained

ground in other periodicals.

1931 saw his first collection of verses, Hard Lines,

published with illustrations by Otto Sogolow. The book was a great

success and seven printings were sold out in 1931. Nash was making

forty dollars a week writing these verses which was better than his

advertising job paid him. He took a position on the staff of the New

Yorker in 1932 but wrote on

a free-lance basis. Between

1930 and his death in 1971 he placed 329 poems in the magazine.

The

targets of his

satirical verse were hardly offended, for they often laughed as much

as other readers, at noticing their failings displayed in such comic

ways.

After

Nash married in 1931 and brought a family into the world he wrote The

Bad Parents’ Garden of Verse.

As the father of two little girls he wrote Song to be Sung

by the Father of Six-months-old-Female Children:

I

never see an infant (male),

A-sleeping

in the sun,

Without

I turn a trifle pale

And

think is he the one?

Oh,

first he'll want to crop his curls,

And

then he'll want a pony,

And

then he'll think of pretty girls,

…

Oh

sweet be his slumber and moist his middle!

My

dreams, I fear, are infanticiddle.

A

fig for embryo Lohengrins!

I'll

open all his safety pins,

I'll

pepper his powder, and salt his bottle,

And

give him readings from Aristotle.

Sand

for his spinach I'll gladly bring,

And

Tabasco sauce for his teething ring.

And

an elegant, elegant, alligator

To

play with him in his perambulator.

Then

perhaps he'll struggle through fire and water

To

marry somebody else's daughter.

Nash

was a hypochondriac. A collection of his medical complaints, comic,

of course, appeared in Bed

Riddance. Typical is Fahrenheit

Gesundheit:

Nothing

is glummer

Than

a cold in the summer.

A

summer cold

Is

to have and to hold.

A

cough in the fall

Is

nothing at all,

A

winter snuffle

Is

lost in the shuffle

And

April sneezes

Put

leaves on the treeses,

But

a summer cold

Is

to have and to hold.

…

Oh,

would it were curable

Rather

than durable;

Were

it Goering’s or Himmler’s,

Or

somebody simlar’s!

O

Chi Minh, were it thine!

But

it isn’t, it’s mine.

A

summer cold

Is

to have and to hold.

Ogden

Nash had

a stint in Hollywood from 1936 to 1942. He wrote three screenplays

for MGM but none was a hit. He made good money however. Nash met the

humorist S. J. Perelman in Hollywood and became friends. They agreed

to collaborate on a musical, based

on a book by Perelman, with

lyrics by Nash, and music by Weill. It was One Touch

of Venus, which became a big hit

in 1943 on Broadway and ran for 567 performances.

Nash

later gave himself over to writing children’s poems in the 50s and

60s, but his other line, that

of

whimsical poems, continued to pour from his pen. Custard

the Dragon, the poem read

by Pamela, was written in 1959.

The

critic Blair terms humour of the variety of Ogden Nash (as well as

James Thurber’s) as the “dementia praecox” school of humour. He

could consciously introduce spelling errors to accord with rhyme, for

example, in the limerick Arthur:

There

was an old man of Calcutta,

Who

coated his tonsils with butta,

Thus

converting his snore

From

a thunderous roar

To

a soft, oleaginous mutta.

Many

of Nash’s shorter poems are like

pithy aphorisms:

It

is easier for one parent to support seven children than for seven

children to support one parent.

Undoubtedly,

close observation of the world has led him to this and other

perceptive conclusions.

One critic called Nash “a philosopher, albeit a laughing one,”

who writes about the “vicissitudes and eccentricitudes of domestic

life as they affected an apparently gentle, somewhat bewildered man.”

When

Nash died in 1971, farewell tributes were

rendered to him in imitation of his mangled meter. For example, the

poet Morris Bishop wrote:

Free

from flashiness, free from trashiness,

Is

the essence of ogdenashiness.

Rich,

original, rash and rational

Stands

the monument ogdenational.

Nash’s

work remained unique. Many others have

demonstrated a gift for repartee or cutting observation, but none in

the sustained, good-humoured, rule-breaking manner of

Ogden Nash. “He is easy to imitate badly, impossible to imitate

well,” said a critic upon his death.

Thommo

referred to a song Puff,

the Magic Dragon.

Noble

kings and princes would bow

whenever

they came.

Pirate

ships would lower their flags

when

Puff roared out his name.

Oh!

Puff

the magic dragon lived by the sea

and

frolicked in the autumn mist

in

the land called Honah Lee.

Saras

Saras

also chose Ogden Nash, reading the poem called The Boy Who

Laughed at Santa Claus. It’s

about this boy called Jabez Dawes who didn’t believe in Santa Claus

(Saint Nicholas) and

takes his heresy viral:

Like

whooping cough, from child to child,

He

sped to spread the rumor wild:

'Sure

as my name is Jabez Dawes

There

isn't any Santa Claus!'

Jabez Dawes Christmas Eve surprise

And

then comes his reckoning when Santa Claus comes down the chimney:

'Jabez'

replied the angry saint,

'It

isn't I, it's you that ain't.

Although

there is a Santa Claus,

There

isn't any Jabez Dawes!'

The

final verse tells people to beware of sneering at Santa Claus, for

Donner and Blitzen (the names

of two

of the eight reindeers in

lore who pull

the sleigh of Santa Claus) licked the paint off

Jabez Dawes! You can listen

to a startling

presentation of the poem on Youtube.

Saras

quoted a 4-liner from the pen of Nash:

To

keep your marriage brimming

with

love in the loving cup,

Whenever

you’re wrong, admit it;

Whenever

you’re right, shut up.

This

is from a poem called A Word to Husbands.

Here

below is a commemorative postage stamp in honour of the poet:

Ogden Nash - A 37¢ commemorative stamp for the poet was issued on his birth centenary, Aug. 19, 2002

These

be the poems that can be traced on the stamp:

The

turtle lives 'twixt plated decks

Which

practically conceal its sex.

I

think it clever of the turtle

In

such a fix to be so fertile.

The

cow is of the bovine ilk;

One

end is moo, the other is milk.

Senescence

begins

And

middle-age ends

The

day your descendants

Outnumber

your friends.

The

trouble with a kitten is

THAT

eventually

it becomes a

CAT.

An

elderly bride of Port Jervis

Was

quite understandably nervis

Since

her apple-cheeked groom

With

three wives in the tomb

Kept

insuring her during the servis.

The

camel has a single hump;

The

dromedary, two;

Or

else the other way around.

I'm

never sure. Are you?

A

PDF

file on poemhunter.com contains a plethora of Ogden

Nash verses.

Geetha

Geetha

took up a poem of Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809 –

1894) which satirises the

well-known poem of Longfellow, A Psalm of Life.

That poem written to inspire

people to greater effort in their lives,

begins:

Tell

me not, in mournful numbers,

Life

is but an empty dream!

For

the soul is dead that slumbers,

And

things are not what they seem.

Life

is real! Life is earnest!

And

the grave is not its goal;

Dust

thou art, to dust returnest,

Was

not spoken of the soul.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. ca.1879

To

give a good dusting to this old poem Holmes responds:

“Life

is real, life is earnest,

And

the shell is not its pen –

“Egg

thou art, and egg remainest”

Was

not spoken of the hen.

Thommo

said a notable phrase lifted from Longfellow’s poem is “footprints

on the sands of time” taken from this stanza:

Lives

of great men all remind us

We

can make our lives sublime,

And,

departing, leave behind us

Footprints

on the sands of time;

This

is parodied and transformed by Holmes into:

Lives

of roosters all remind us,

We

can make our lives sublime,

And

when roasted, leave behind us,

Hen

tracks on the sands of time.

There

was laughter among readers thinking of hen-tracks on the sands of

time!

Holmes

was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1809, and died there in

1894.

After

graduating from Harvard College, he studied study of law before

turning to medicine for a career. He took his medical degree in 1836.

He taught Anatomy and Physiology in Dartmouth College, New Hampshire.

In 1847 he assumed a similar position at Harvard University holding

it until 1892. All of his literary work was performed as a sideline

to his medical work during forty-seven years.

His

literary tastes ran to comic and satiric verse. He contributed his

verses to American periodicals, generally written for occasions; in

1836 he published a collection. His main life work was teaching and

practice as a doctor. The poems he wrote were first declaimed in the

literary societies of the college.

He

published prose reflections, in 1858, titled The Autocrat

of the Breakfast Table, essays

carrying a genial strain of humour. His was an aphoristic train of

thought and he is quoted for may of his pithy maxims. This was

followed by other volumes, The Professor at the Breakfast

Table, and later by The

Poet at the Breakfast Table. The

latter is full of liberal thinking. He was also author of a valuable

medical work on puerperal fever.

When

the civil war (1862-1865) broke out, Holmes wrote war lyrics during

the conflict to inspire others,

displaying the simple patriotism of the Americans who fought for

independence from the British a hundred years earlier.

His son of the same name

with Jr. as postfix

became Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1902 to 1932.

Holmes

wrote a number of memorable poems. He wrote a magnificent poem, Old

Ironsides, that aroused

people to protest against a

famous

old warship being broken up

for scrap:

Her

deck, once red with heroes' blood,

Where

knelt the vanquished foe,

When

winds were hurrying o'er the flood,

And

waves were white below,

No

more shall feel the victor's tread,

Or

know the conquered knee;—

The

harpies of the shore shall pluck

The

eagle of the sea!

Old Ironsides, the USS Constitution

Many

of his sayings must stand among the finest specimens of American wit

and humour:

It

is the province of knowledge to speak, and it is the privilege of

wisdom to listen.

Men

do not quit playing because they grow old; they grow old because they

quit playing.

Holmes

harboured striking and original thoughts. In his time he stood out as

brilliant exemplar of the American mind at its most free and liberal.

(See:

Devika

The

poet chosen was James Thomas Fields (1817 – 1881), an American

publisher and author.

Fields

was born in Portsmouth, NH. His father was a sea captain and died

before Fields was three. At the age of 14, Fields took a job at the

Old Corner Bookstore in Boston. His first published poetry was

included in the Portsmouth Journal in 1837 but he drew more

attention when, on September 13, 1838, he delivered his Anniversary

Poem to the Boston Mercantile Library Association.

James Thomas Fields

In

1839, he joined William Ticknor and became junior partner in the

publishing and bookselling firm known as Ticknor and Fields, and

later in 1868 as Fields, Osgood & Company. With this company,

Fields became the publisher of leading contemporary American writers,

with whom he was on terms of close personal friendship. He was also

the American publisher of some of the best-known British writers of

his time, some of whom he also knew intimately. The first collected

edition of Thomas De Quincey's works (20 vols., 1850-1855) was

published by his firm. As a publisher, he was characterised by a

somewhat rare combination of keen business acumen and sound,

discriminating literary taste. He was known for his geniality and

charm of manner. Ticknor and Fields built their company to have a

substantial influence in the literary scene, which writer and editor

Nathaniel Parker Willis acknowledged in a letter to Fields: "Your

press is the announcing-room of the country's Court of Poetry."

In

1854, Fields married his second wife, Annie Adams, who was an author

herself.

Ticknor

and Fields purchased The Atlantic Monthly for $10,000 and,

about two years later in May 1861, Fields took over the editorship

when James Russell Lowell left. In 1871, he retired from business and

from his editorial duties and devoted himself to lecturing and

writing. He also edited, with Edwin P. Whipple, A Family Library

of British Poetry (1878).

Fields

died in Boston on April 24, 1881. He is buried at Mount Auburn

Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. This

biography of Fields is taken from poemhunter.com

By

joining KRG, Devika said, she has come to appreciate poetry and the

group has fostered her interest. She talked to her

daughter who recited this poem, The Owl-Critic, at a

competition and won a prize. Devika decided to do it for us. Through

reading the poem she got acquainted with James Audubon, the American

ornithologist whose name is attached to the premier organisation in

America concerned with birds and bird-watching, The

National Audubon Society. The other naturalist and writer who is

referred to in the poem is John

Burroughs:

Examine

those eyes.

I’m

filled with surprise

Taxidermists

should pass

Off

on you such poor glass;

So

unnatural they seem

They’d

make Audubon scream,

And

John Burroughs laugh

To

encounter such chaff.

…

How

flattened the head is, how jammed down the neck is—

In

short, the whole owl, what an ignorant wreck ’tis!

I

make no apology;

I’ve

learned owl-eology.

There

are lots of crazy rhymes in the poem that add to the humour. It

culminates with a funny resolution:

Just

then, with a wink and a sly normal lurch,

The

owl, very gravely, got down from his perch,

Walked

round, and regarded his fault-finding critic

(Who

thought he was stuffed) with a glance analytic,

And

then fairly hooted, as if he should say:

“Your

learning’s at fault this time, anyway;

Don’t

waste it again on a live bird, I pray.

I’m

an owl; you’re another. Sir Critic, good-day!”

Everyone

had a good laugh. Geetha said it was an unexpected anti-climax.

Hemjit

Hemjit

selected two short poems of Robert Burns, the national poet of

Scotland. Joe has provided an extensive

biography of Burns at an earlier reading in June this year when

we read the Romantic Poets. Hemjit

mentioned that Scots is a Germanic language spoken in Scotland, and

there is also Scottish English which may be seen as a dialect of

English, along the lines of what Robert Burns wrote. Burns had a

natural gift for poetry

and wrote for many public occasions.

He was a philanderer who sired many children, in and out of wedlock,

and was quite comfortable

with having

casual affairs. Some

consider him the ‘greatest Scot of all time.’

Robert Burns statue, Schenley Park, Pittsburgh

Both

the poems concern ‘henpecked’ men, and the term occurs in the

titles. The question was raised whether the term is obsolete in the

era of supposed gender-equality. There certainly have existed men in

all times and everywhere who have been dominated by women; although,

in general, it is the

women who have been

subjugated in

patriarchal

societies around the world.

As for cuckolded men, it is

merely parallel to the more

numerous cases of men who

have been unfaithful to their wives.

In

the first poem Burns proves he belongs to the entrenched tribe of

patriarchs by cursing the wife of a henpecked husband thus:

I'd

charm her with the magic of a switch,

I'd

kiss her maids, and kick the perverse bitch.

Regarding

his philandering leading to numerous children out of wedlock, Joe

ventured the poet was laying women on

the one hand, and

also, like a hen, laying

poet-ets or poet-ettes along the way. Hemjit

said Burns was more amoral than immoral. Hence, Thommo noted, to

laughter, he was entitled to the sobriquet, ‘greatest Scot.’

The

second poem on the epitaph of a henpecked country squire was notably

enjoyed by the women in the group, as Thommo remarked. The lines read

Here

lies man a woman ruled,

The

devil ruled the woman.

Obviously,

it is

not the

deceased squire, but Rabbie Burns who is speaking.

Shoba

Fireflies

by Rabindranath Tagore was Shoba’s choice of a happy poem for

this session. It is really a book of 256 verses with short lines that

sound like proverbs or maxims. Shoba chose the first fourteen. Such

verses were common in China and Japan where they were often written

on lengths of silk and called ‘fireflies.’ When Tagore visited

Japan he collected them in his notebooks. Each ‘firefly’ is short

and represents a fleeting thought on the verities of existence. They

were gathered in a book containing a decorative design by Boris

Artzybasheff on each page with a short ‘firefly’ of Tagore's

below. At the end stood Tagore's Nobel Acceptance Speech. The poet’s

biography has been treated in adequate detail in several blog

posts when KRG celebrated his 150th birth anniversary in 2011.

Fireflies - The original edition of Tagore's maxims

The

complete

Set of 256 Fireflies may be read at this linked site.

Tagoreweb.in is an awesome,

total, and complete collection of everything Rabindranath Tagore

wrote.

A page from Fireflies by Rabindranath Tagore with illustrations by Artzybasheff (click to enlarge)

Shoba was fascinated by the names of Rabindranath’s brothers –Dwijendranath, Ganendranath, Satyendranath, Hemendranath, etc. – all given by their father, Debendranath.

To

answer a question raised by Shoba, these short verses were composed

by Rabindranath in English originally, not translated from Bengali.

Saras loved the line:

The

tree gazes in love at its own beautiful shadow

which

yet it never can grasp.

On

a trip to Malaysia Thommo saw trees full of fireflies along a riverside. They had to go on a punt so that the fireflies would not be disturbed. Thommo also mentioned the Te Anau cave in New Zealand, which they didn't have time to visit. Lake Te Anau in

New Zealand leads to amazing 12,000 year-old caves, carved into

incredible swirling shapes by the force of the river that flows

through them. You can travel through the passages on foot and by

boat to find a grotto of thousands of glittering glowworms, native

to New Zealand:

Te Anau cave glow worms, native to New Zealand

Fireflies

or glowworms are called minna-minni in Malayalam, said Shoba.

KumKum

T.

S. Eliot (TSE) was born in 1888 and died in 1965. He has been

read several times before. KumKum provided a short introduction. He

was one of the twentieth century’s major poets. Besides he was an

essayist, playwright, and literary critic.

T.S. Eliot, young in 1919 - Photograph by E.O. Hopp-Corbis Images

Eliot

was born in St. Louis, Missouri, on Sept 26, 1888. His parents were

from a wealthy Boston family. Eliot studied philosophy at Harvard and

earned his degree in three years instead of the usual four; he then

finished a Master’s degree in English Literature by his fourth

year. But his studies in Harvard were undistinguished, so much so

that his parents got a warning he might be rusticated for his poor

grades. [See https://harvardmagazine.com/2015/07/the-young-t-s-eliot,

to learn about Eliot’s career in Harvard and how it enriched his

poetry]

He

studied further at Oxford, and settled down in England. His career

branched in many directions. To begin with he was a school-teacher,

then he became a clerk in Lloyd's bank. Eventually, he rose to be the

literary editor for the publishers, Faber & Faber. Later, he

became a director of the company. Eliot edited Criterion, an

important literary journal of that time started by him.

Eliot

became a British citizen as he comfortably embraced British culture,

its intellectual sophistication at that time, and of course, their

way of life. After finishing his studies at Oxford, he romanced and

married an accomplished young British woman, Vivienne. But, this

marriage did not work for either of them. They were separated until

she died of heart disease in an asylum in 1947.

In

1957, at the age of 68, Eliot married Valerie Fletcher, his secretary

at Faber and Faber, who was 30 at the time. Theirs was a happy

marriage.

TS Eliot to his secretary Miss Valerie Fletcher ...

Religion

played an important role in Eliot's thinking. His philosophical

approach to life is expressed in all his writings.

Eliot

received many awards for his literary works. He was honoured with the

Order of Merit in 1948 and the Nobel Prize in Literature, also in

1948; the citation read: “for his outstanding, pioneer contribution

to present-day poetry.”

T.

S. Eliot died in London on Jan 4, 1965. Valerie, his widow, lived on

till 2012.

Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats - first edition, 1939

Old

Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, from which Zakia and KumKum

were reading at the session, was published in 1939. ‘Possum’ was

Eliot's nickname, given him by Ezra Pound, his editor and

collaborator in the long poem, The Waste Land. More than forty

years later, the famous British composer and conductor, Andrew Lloyd

Webber, turned the cat poems into the very successful and popular

musical, Cats, which played for decades on the New York and

London stage, earning a fortune in royalties for Eliot’s estate.

Andrew Lloyd Webber and second wife Sarah Brightman, with the original cast of Cats - it was the longest running Broadway show of all time when it closed in 2000

Joe

elaborated KumKum’s note on Eliot to enhance the understanding of a

poetic career which is key to the development of English poetry and

the entry into modernism. The original poem that first brought TSE to

the notice of the poetry world was The Love Song of J. Alfred

Prufrock published in 1915, although written as early as 1911

when he was barely 22. The images that hallucinate the poem describe

nothing about Prufrock, but they were seductive and alluring, even

though fragmented. Some of its lines will remain stamped forever in

the poetic imagination of English readers and poets:

Let

us go then, you and I,

When

the evening is spread out against the sky

Like

a patient etherised upon a table;

What

do we make of the Italian quotation at the head of the poem? It is

Guido da Montefeltro speaking to the poet Dante Alighieri in Hell

from Dante’s Inferno:

If I but thought that my response were made

to one perhaps returning to the world,

this tongue of flame would cease to flicker.

But since, up from these depths, no one has yet

returned alive, if what I hear is true,

I answer without fear of being shamed.

to one perhaps returning to the world,

this tongue of flame would cease to flicker.

But since, up from these depths, no one has yet

returned alive, if what I hear is true,

I answer without fear of being shamed.

So, is the whole poem a warning from the other side? But look at the

images that follow:

The

yellow fog that rubs its back upon the window-panes,

The

yellow smoke that rubs its muzzle on the window-panes,

Licked

its tongue into the corners of the evening,

How

memorable is that!

Shall

I part my hair behind? Do I dare to eat a peach?

I

shall wear white flannel trousers, and walk upon the beach.

I

have heard the mermaids singing, each to each.

Is

this finally the timid Prufrock trying to make his tentative presence

known to the world?

One

wonders how TSE came to write at such a young age (27):

I

grow old … I grow old ...

I

shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled.

The

very vocabulary of poetry changed forever, and you could write no

longer as earlier poets wrote. That was the measure of TSE’s

influence. The Waste Land in 1922 continued the revolution,

though Eliot later confessed he did not quite grasp himself what he

was accomplishing.

Eliot, however, was influenced not by English poets before him, but by the French Symbolist poets of whom he had read: Gérard de Nerval, Stéphane Mallarmé, Paul Verlaine, and Arthur Rimbaud. But the greatest influence which he himself acknowledged came from Jules Laforgue, whom he referred to in these words:

Eliot, however, was influenced not by English poets before him, but by the French Symbolist poets of whom he had read: Gérard de Nerval, Stéphane Mallarmé, Paul Verlaine, and Arthur Rimbaud. But the greatest influence which he himself acknowledged came from Jules Laforgue, whom he referred to in these words:

If

not quite the greatest French poet since Baudelaire …

certainly the most important technical innovator.

[T.S.

Eliot, Introduction to Selected Poems of Ezra Pound, 1928]

Thus

Eliot’s greatest debt was not to an English language poet but to

the French Symbolists, in particular, Jules Laforgue.

Of

Laforgue I can say he was the first to teach me how to speak, to

teach me the poetic possibilities of my own idiom of speech.

To

Laforgue I owe more than I owe to any poet in any language.

(1960)

The

way Laforgue weaves philosophical ideas into his poems and keeps his

own person and emotion away from the poem, is quite characteristic of

Eliot also.

Of

his early work, Eliot has said:

The

form in which I began to write, in 1908 or 1909, was directly drawn

from the study of Laforgue, together with the later Elizabethan

drama; and I do not know anyone who started from exactly that point.

Elsewhere

Eliot said:

The

kind of poetry that I needed, to teach me the use of my own voice,

did not exist in English at all; it was only found in French.

Leonard

Unger concludes that “In so far as Eliot started from an exact

point it was emphatically and exclusively from Laforgue.”

[The

above is taken from

https://www.gresham.ac.uk/short/t-s-eliots-poetic-inspiration-jules-laforgue/]

TSE’s

familiarity with Jules Laforgue, who was never considered more than a

minor poet in France, came from reading the British critic Arthur

Symons's book, The Symbolist Movement in Literature while at

Harvard in 1908 browsing in a library. He was impressed with the

lines from Laforgue he read and not finding Laforgue’s poetry

available in Harvard procured them from Paris. His notebooks of those

years were published later under the title Inventions of the March

Hare, much after his death. It contains many parodies of

Laforgue’s style. But it was when he spent an academic year in

Paris and Munich in 1911 that he found his own voice via Prufrock,

and thus became the acknowledged torchbearer of modernity in in English

poetry.

TSE wrote in 1930 while writing a review in the Criterion:

I owe Mr. Symons a great debt: but for having read his book I should not, in the year 1908, have heard of Laforgue or Rimbaud; I should probably not have begun to read Verlaine; but for reading Verlaine, I should not have heard of Corbière. So the Symons book is one of those which have affected the course of my life.

In

1912 Eliot returned to Harvard, and assumed a seriousness of study

heretofore missing. He studied Sanskrit, and intended to write a

thesis on the philosopher F.H. Bradley. But the Harvard

saga came to an end when he left for Oxford in 1914 as a 25-year-old,

fully intending to return and complete his Ph.D. after a year or two

in Oxford. But there he met and married Vivienne Haigh-Wood, after

knowing her for a few months, in June 1915. It turned out to be a disastrous

marriage. Eliot writes:

I

believe I came to persuade myself that I was in love with her simply

because I wanted to burn my boats and commit myself to staying in

England.

In

letters published later on one can see how completely enraptured

TSE was with his second wife, Valerie.

Eliot

issued his Collected Poems 1909-1962 before his death, which

was just 240 pages long. It’s the volume we are all familiar with.

However, Faber and Faber, his publisher issued in 2015 the

authoritative edition, The Poems of T.S. Eliot, Volume 1

(Collected and Uncollected Poems) & Volume 2 (Practical

Cats and Further Verses), which have commentary and notes on drafts

and correspondence which throw light on the poet’s manner of

working; about two-thirds of Vol 1 are notes. Together they comprise

over 2,100 pages.

Regarding

Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, the

British Library has a trove of TSE’s letters where they first

appeared in the affectionate correspondence with members of the Tandy

family (Geoffrey, his wife Doris (Polly), and their three children

Richard, Alison, and Anthea). Geoffrey was a broadcaster for the BBC.

A

letter sent on 10 November 1936 to Alison, the daughter, contains a

draft of The Old Gumbie Cat:

T.S. Eliot - Draft of The Old Gumbie cat (click to enlarge)

This

was the poem read by KumKum. Eliot’s fond relations with the Tandy

family inspired him to write these pieces, much as Lewis Carroll was

inspired to write Alice in Wonderland for a friend’s

daughter, Alice Liddell, aged 10, who asked him to write the story

down after he had narrated it to her and her sisters on a boat ride.

He did soon after, and the name he gave was Alice's Adventures

Under Ground. The marvellous manuscript of that classic, including

drawings, in Lewis Carroll’s hand is on the British Library web

also:

Show

the link to any child (or adult child) for a thrilling diversion.

The

universal favourite among the Cat poems is Macavity the Mystery

Cat, which was read by Zakia.

Zakia

TSE

seems to reach a fluidity of versification and wonderful choice of

words and images that he has never surpassed in his more serious

poetry. Look at these imaginative metaphors:

Macavity,

Macavity, there’s no one like Macavity,

He’s

broken every human law, he breaks the law of gravity.

His

powers of levitation would make a fakir stare,

And

when you reach the scene of crime—Macavity’s not there!

..

And

when the loss has been disclosed, the Secret Service say:

It

must have been Macavity!’—but he’s a mile away.

You’ll

be sure to find him resting, or a-licking of his thumb;

Or

engaged in doing complicated long division sums.

Macavity,

Macavity, there’s no one like Macavity,

There

never was a Cat of such deceitfulness and suavity.

He

always has an alibi, and one or two to spare:

At

whatever time the deed took place—MACAVITY WASN’T THERE !

Joe

wrote a parody of this poem with Osama bin Laden as the Mystery Fox

when 9/11 happened in America. Here’s the third verse paralleling

that of Macavity:

Osama's

a mujahid, he's very tall and thin;

You

would know him if you saw him, for his eyes are sunken in.

His

brow is deeply lined with thought, his head is highly domed;

His

Kalashnikov is ready, and his beard is uncombed.

He

points his finger at the world, which he proceeds to shake;

And

you may think he's half asleep, but he's always wide awake.

We

all laughed at the last verse of The Old Gumbie Cat:—

She

thinks that the cockroaches just need employment

To

prevent them from idle and wanton destroyment.

So

she's formed, from that lot of disorderly louts,

A

troop of well-disciplined helpful boy-scouts,

With

a purpose in life and a good deed to do—

And

she's even created a Beetles' Tattoo.

Thommo

notes that in 1987 he heard of TSE for the first time at a service in

St. Paul’s Cathedral, Calcutta. But it wasn’t regarding his

poetry.

Thommo

Thommo’s

poem was the well-known poem of Walt Whitman, Song of the Open

Road. Thommo remembered that Joe used the opening verse to

introduce the travelogue he had written called, On the Road Again,

about travels through 27 countries in a Hyundai i2o in 2016.

Rahul, Thommo, Miriam, Geetha, and Kunju at Thommo's book release on Jan 3, 2013 ‘Atop the World’

Song

of the Open Road is an epic poem. Because of its length Thommo

read only the first, fifth and last sections. It lays out the liberal

and open gaze upon the world that Walt Whitman cherished. The poem

itself grew by accretion, as did the Leaves of Grass (LG) of which

it formed a part from the second edition onward. In Song of

Myself Whitman writes an oft-quoted verse of his:

Do

I contradict myself?

Very

well then I contradict

myself,

I

am large, I contain multitudes.

Whitman’s

subject was America, a new awakening America, and he observed it in

all its particulars and gave voice to its future. A useful reference

to read is Guide

to Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass at poets.org

The

Song of the Open Road ends with a magnificent invitation:

Camerado,

I give you my hand!

I

give you my love more precious than money,

I

give you myself before preaching or law;

Will

you give me yourself? will you come travel with me?

Shall

we stick by each other as long as we live?

“I

SHALL,” exclaimed Geetha joyfully. Thommo declared it was 39 years

since she said that to him!

The

poet’s biography has been treated before adequately at

a session of KRG poetry in 2011. Sections of his poem, LG, have

been interpreted as paeans to homosexual love and that community of

people has embraced him, but it is not clear. He himself disavowed

it, but he did have close friendships with men and boys throughout

his life. Nobody has verified his claim that he fathered six

illegitimate children. You can read more at Whitman’s

wiki site. The critic Harold Bloom considers the first edition of

Leaves of Grass as a kind of secular scripture of America.

Regarding

his latent homosexuality you can read the article Walt

Whitman, Prophet of Gay Liberation. In any event, the verses he

wrote are the mildest expressions of poetic homosexual longing, and

would scarce raise an eyebrow now, said Thommo. One is surprised to

learn that Whitman began his literary career as a novelist. Franklin

Evans, or The Inebriate: A Tale of the Times was his only

novel, written in 1842 at a time when the Temperance movement was

strong. It became his most popular work and sold ~20,000 copies.

When

the session came to

an end, KumKum pronounced it was a lovely session. Shoba agreed,

saying we loved all the poems.

Dinner Pics

The Poems

Gopa – poems by Spike Milligan (1918 – 2002)

1. A Combustible Woman from Thang

A combustible woman from Thang

Exploded one day with a BANG!

The maid then rushed in

And said with a grin,

'Pardon me, madam - you rang?'

2. Scorflufus

There are many diseases,

That strike people's kneeses,

Scorflufus! is one by name

It comes from the East

Packed in bladders of yeast

So the Chinese must take half the blame.

There's a case in the files

Of Sir Barrington-Pyles

While hunting a fox one day

Shot up in the air

And remained hanging there!

While the hairs on his socks turned grey!

Aye! Scorflufus had struck!

At man, beast, and duck.

And the knees of the world went Bong!

Some knees went Ping!

Other knees turned to string

From Balham to old Hong Kong.

Should you hold your life dear,

Then the remedy's clear,

If you're offered some yeast - don't eat it!

Turn the offer down flat-

Don your travelling hat-

Put an egg in your boot - and beat it!

3. The ABC

'Twas midnight in the schoolroom

And every desk was shut

When suddenly from the alphabet

Was heard a loud "Tut-Tut!"

Said A to B, "I don't like C;

His manners are a lack.

For all I ever see of C

Is a semi-circular back!"

"I disagree," said D to B,

"I've never found C so.

From where I stand he seems to be

An uncompleted O."

C was vexed, "I'm much perplexed,

You criticise my shape.

I'm made like that, to help spell Cat

And Cow and Cool and Cape."

"He's right" said E; said F, "Whoopee!"

Said G, "'Ip, 'Ip, 'ooray!"

"You're dropping me," roared H to G.

"Don't do it please I pray."

"Out of my way," LL said to K.

"I'll make poor I look ILL."

To stop this stunt J stood in front,

And presto! ILL was JILL.

"U know," said V, "that W

Is twice the age of me.

For as a Roman V is five

I'm half as young as he."

X and Y yawned sleepily,

"Look at the time!" they said.

"Let's all get off to beddy byes."

They did, then "Z-z-z."

4. On the Ning Nang Ning

On the Ning Nang Nong

Where the Cows go Bong!

and the monkeys all say BOO!

There's a Nong Nang Ning

Where the trees go Ping!

And the tea pots jibber jabber joo.

On the Nong Ning Nang

All the mice go Clang

And you just can't catch 'em when they do!

So its Ning Nang Nong

Cows go Bong!

Nong Nang Ning

Trees go ping

Nong Ning Nang

The mice go Clang

What a noisy place to belong

is the Ning Nang Ning Nang Nong!!

5. Smiling is infectious

Smiling is infectious,

you catch it like the flu,

When someone smiled at me today,

I started smiling too.

I passed around the corner

and someone saw my grin.

When he smiled I realized

I'd passed it on to him.

I thought about that smile,

then I realized its worth.

A single smile, just like mine

could travel round the earth.

So, if you feel a smile begin,

don't leave it undetected.

Let's start an epidemic quick,

and get the world infected!

1. A Combustible Woman from Thang

A combustible woman from Thang

Exploded one day with a BANG!

The maid then rushed in

And said with a grin,

'Pardon me, madam - you rang?'

2. Scorflufus

There are many diseases,

That strike people's kneeses,

Scorflufus! is one by name

It comes from the East

Packed in bladders of yeast

So the Chinese must take half the blame.

There's a case in the files

Of Sir Barrington-Pyles

While hunting a fox one day

Shot up in the air

And remained hanging there!

While the hairs on his socks turned grey!

Aye! Scorflufus had struck!

At man, beast, and duck.

And the knees of the world went Bong!

Some knees went Ping!

Other knees turned to string

From Balham to old Hong Kong.

Should you hold your life dear,

Then the remedy's clear,

If you're offered some yeast - don't eat it!

Turn the offer down flat-

Don your travelling hat-

Put an egg in your boot - and beat it!

3. The ABC

'Twas midnight in the schoolroom

And every desk was shut

When suddenly from the alphabet

Was heard a loud "Tut-Tut!"

Said A to B, "I don't like C;

His manners are a lack.

For all I ever see of C

Is a semi-circular back!"

"I disagree," said D to B,

"I've never found C so.

From where I stand he seems to be

An uncompleted O."

C was vexed, "I'm much perplexed,

You criticise my shape.

I'm made like that, to help spell Cat

And Cow and Cool and Cape."

"He's right" said E; said F, "Whoopee!"

Said G, "'Ip, 'Ip, 'ooray!"

"You're dropping me," roared H to G.

"Don't do it please I pray."

"Out of my way," LL said to K.

"I'll make poor I look ILL."

To stop this stunt J stood in front,

And presto! ILL was JILL.

"U know," said V, "that W

Is twice the age of me.

For as a Roman V is five

I'm half as young as he."

X and Y yawned sleepily,

"Look at the time!" they said.

"Let's all get off to beddy byes."

They did, then "Z-z-z."

4. On the Ning Nang Ning

On the Ning Nang Nong

Where the Cows go Bong!

and the monkeys all say BOO!

There's a Nong Nang Ning

Where the trees go Ping!

And the tea pots jibber jabber joo.

On the Nong Ning Nang

All the mice go Clang

And you just can't catch 'em when they do!

So its Ning Nang Nong

Cows go Bong!

Nong Nang Ning

Trees go ping

Nong Ning Nang

The mice go Clang

What a noisy place to belong

is the Ning Nang Ning Nang Nong!!

5. Smiling is infectious

Smiling is infectious,

you catch it like the flu,

When someone smiled at me today,

I started smiling too.

I passed around the corner

and someone saw my grin.

When he smiled I realized

I'd passed it on to him.

I thought about that smile,

then I realized its worth.

A single smile, just like mine

could travel round the earth.

So, if you feel a smile begin,

don't leave it undetected.

Let's start an epidemic quick,

and get the world infected!

Joe – poem by Saint Francis (1181 – 1226)

Il Cantico de Frate Sole

Il Cantico de Frate Sole

1. Altissimu, onnipotente bon Signore,

Tue so le laude, la gloria e l’honore et onne benedictione.

2. Ad Te solo, Altissimo, se konfano,

et nullu homo ène dignu te mentouare.

3. Laudato sie, mi Signore cum tucte le Tue creature,

spetialmente messor lo frate Sole,

lo qual è iorno, et allumini noi per lui.

4. Et ellu è bellu e radiante cum grande splendore:

de Te, Altissimo, porta significatione.

5. Laudato si, mi Signore, per sora Luna e le stelle:

in celu l’ài formate clarite et pretiose et belle.

6. Laudato si, mi Signore, per frate Uento

et per aere et nubilo et sereno et onne tempo,

per lo quale, a le Tue creature dài sustentamento.

7. Laudato si, mi Signore, per sor’Acqua,

la quale è multo utile et humile et pretiosa et casta.

8. Laudato si, mi Signore, per frate Focu,

per lo quale ennallumini la nocte:

ed ello è bello et iucundo et robustoso et forte.

9. Laudato si, mi Signore, per sora nostra matre Terra,

la quale ne sustenta et gouerna,

et produce diuersi fructi con coloriti fior et herba.

10. Laudato si, mi Signore, per quelli ke perdonano per lo Tuo amore

et sostengono infirmitate et tribulatione.

11. Beati quelli ke ‘l sosterranno in pace,

ka da Te, Altissimo, sirano incoronati.

12. Laudato si mi Signore, per sora nostra Morte corporale,

da la quale nullu homo uiuente pò skappare:

13. Guai a quelli ke morrano ne le peccata mortali;

beati quelli ke trouarà ne le Tue sanctissime uoluntati,

ka la morte secunda no ‘l farrà male.

14. Laudate et benedicete mi Signore et rengratiate

e seruiteli cum grande humilitate.

[Notes: so=sono, si=sii (you are), mi=mio, ka=perché, u replaces v, sirano=saranno]

The Canticle of the Sun

1 Most High, all-powerful, good Lord,

Yours are the praises, the glory, the honour, and all blessing.

2. To You alone, Most High, do they belong,

and no man is worthy to mention Your name.

3. Praised be You, my Lord, with all your creatures,

especially Sir Brother Sun,

Who is the day and through whom You give us light.

4. And he is beautiful and radiant with great splendour;

and bears a likeness of You, Most High One.

5. Praised be You, my Lord, through Sister Moon and the stars,

in heaven You formed them clear and precious and beautiful.

6. Praised be You, my Lord, through Brother Wind,

and through the air, cloudy and serene, & every kind of weather

through which You give sustenance to Your creatures.

7. Praised be You, my Lord, through Sister Water,

which is very useful and humble and precious and chaste.

8. Praised be You, my Lord, through Brother Fire,

through whom You light the night

and he is beautiful and playful and robust and strong.

9. Praised be You, my Lord, through our Sister Mother Earth,

who sustains and governs us,

and who produces varied fruits with coloured flowers and herbs.

10. Praised be You, my Lord, through those who give pardon for Your love

and bear infirmity and tribulation.

11. Blessed are those who endure in peace

for by You, Most High, they shall be crowned.

12. Praised be You, my Lord, through our Sister Bodily Death,

from whom no living man can escape.

13. Woe to those who die in mortal sin.

Blessed are those whom death will find in Your most holy will,

for the second death shall do them no harm.

14. Praise and bless my Lord and give Him thanks

and serve Him with great humility.

(translated by Regis Armstrong and Ignatius Brady, taken from Francis and Clare: The Complete Works, (New York: Paulist Press, 1982)

Kavita

Television – Poem by Roald Dahl (1916 – 1990)

The most important thing we've learned,

So far as children are concerned,

Is never, NEVER, NEVER let

Them near your television set --

Or better still, just don't install

The idiotic thing at all.

In almost every house we've been,

We've watched them gaping at the screen.

They loll and slop and lounge about,

And stare until their eyes pop out.

(Last week in someone's place we saw

A dozen eyeballs on the floor.)

They sit and stare and stare and sit

Until they're hypnotised by it,

Until they're absolutely drunk

With all that shocking ghastly junk.

Oh yes, we know it keeps them still,

They don't climb out the window sill,

They never fight or kick or punch,

They leave you free to cook the lunch

And wash the dishes in the sink --

But did you ever stop to think,

To wonder just exactly what

This does to your beloved tot?

IT ROTS THE SENSE IN THE HEAD!

IT KILLS IMAGINATION DEAD!

IT CLOGS AND CLUTTERS UP THE MIND!

IT MAKES A CHILD SO DULL AND BLIND

HE CAN NO LONGER UNDERSTAND

A FANTASY, A FAIRYLAND!

HIS BRAIN BECOMES AS SOFT AS CHEESE!

HIS POWERS OF THINKING RUST AND FREEZE!

HE CANNOT THINK -- HE ONLY SEES!

'All right!' you'll cry. 'All right!' you'll say,

'But if we take the set away,

What shall we do to entertain

Our darling children? Please explain!'

We'll answer this by asking you,

'What used the darling ones to do?

'How used they keep themselves contented

Before this monster was invented?'

Have you forgotten? Don't you know?

We'll say it very loud and slow:

THEY ... USED ... TO ... READ! They'd READ and READ,

AND READ and READ, and then proceed

To READ some more. Great Scott! Gadzooks!

One half their lives was reading books!

The nursery shelves held books galore!

Books cluttered up the nursery floor!

And in the bedroom, by the bed,

More books were waiting to be read!

Such wondrous, fine, fantastic tales

Of dragons, gypsies, queens, and whales

And treasure isles, and distant shores

Where smugglers rowed with muffled oars,

And pirates wearing purple pants,

And sailing ships and elephants,

And cannibals crouching 'round the pot,

Stirring away at something hot.

(It smells so good, what can it be?

Good gracious, it's Penelope.)

The younger ones had Beatrix Potter

With Mr. Tod, the dirty rotter,

And Squirrel Nutkin, Pigling Bland,

And Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle and-

Just How The Camel Got His Hump,

And How the Monkey Lost His Rump,

And Mr. Toad, and bless my soul,

There's Mr. Rat and Mr. Mole-

Oh, books, what books they used to know,

Those children living long ago!

So please, oh please, we beg, we pray,

Go throw your TV set away,

And in its place you can install

A lovely bookshelf on the wall.

Then fill the shelves with lots of books,

Ignoring all the dirty looks,

The screams and yells, the bites and kicks,

And children hitting you with sticks-

Fear not, because we promise you

That, in about a week or two

Of having nothing else to do,

They'll now begin to feel the need

Of having something to read.

And once they start -- oh boy, oh boy!

You watch the slowly growing joy

That fills their hearts. They'll grow so keen

They'll wonder what they'd ever seen

In that ridiculous machine,

That nauseating, foul, unclean,

Repulsive television screen!

And later, each and every kid

Will love you more for what you did.

Pamela

The Tale Of Custard The Dragon – Poem by Ogden Nash (1902 – 1971)

Belinda lived in a little white house,

With a little black kitten and a little gray mouse,

And a little yellow dog and a little red wagon,

And a realio, trulio, little pet dragon.

Now the name of the little black kitten was Ink,

And the little gray mouse, she called her Blink,

And the little yellow dog was sharp as Mustard,

But the dragon was a coward, and she called him Custard.

Custard the dragon had big sharp teeth,

And spikes on top of him and scales underneath,

Mouth like a fireplace, chimney for a nose,

And realio, trulio, daggers on his toes.

Belinda was as brave as a barrel full of bears,

And Ink and Blink chased lions down the stairs,

Mustard was as brave as a tiger in a rage,

But Custard cried for a nice safe cage.

Belinda tickled him, she tickled him unmerciful,

Ink, Blink and Mustard, they rudely called him Percival,

They all sat laughing in the little red wagon

At the realio, trulio, cowardly dragon.

Belinda giggled till she shook the house,

And Blink said Week! , which is giggling for a mouse,

Ink and Mustard rudely asked his age,

When Custard cried for a nice safe cage.

Suddenly, suddenly they heard a nasty sound,

And Mustard growled, and they all looked around.

Meowch! cried Ink, and Ooh! cried Belinda,

For there was a pirate, climbing in the winda.

Pistol in his left hand, pistol in his right,

And he held in his teeth a cutlass bright,

His beard was black, one leg was wood;

It was clear that the pirate meant no good.

Belinda paled, and she cried, Help! Help!

But Mustard fled with a terrified yelp,

Ink trickled down to the bottom of the household,

And little mouse Blink strategically mouseholed.

But up jumped Custard, snorting like an engine,

Clashed his tail like irons in a dungeon,

With a clatter and a clank and a jangling squirm

He went at the pirate like a robin at a worm.

The pirate gaped at Belinda's dragon,

And gulped some grog from his pocket flagon,

He fired two bullets but they didn't hit,

And Custard gobbled him, every bit.

Belinda embraced him, Mustard licked him,

No one mourned for his pirate victim

Ink and Blink in glee did gyrate

Around the dragon that ate the pyrate.

But presently up spoke little dog Mustard,

I'd been twice as brave if I hadn't been flustered.

And up spoke Ink and up spoke Blink,

We'd have been three times as brave, we think,

And Custard said, I quite agree

That everybody is braver than me.

Belinda still lives in her little white house,

With her little black kitten and her little gray mouse,

And her little yellow dog and her little red wagon,

And her realio, trulio, little pet dragon.

Belinda is as brave as a barrel full of bears,

And Ink and Blink chase lions down the stairs,

Mustard is as brave as a tiger in a rage,

But Custard keeps crying for a nice safe cage.

Saras – Poem by Ogden Nash

The Boy Who Laughed at Santa Claus

In Baltimore there lived a boy.

He wasn't anybody's joy.

Although his name was Jabez Dawes,

His character was full of flaws.

In school he never led his classes,

He hid old ladies' reading glasses,

His mouth was open when he chewed,

And elbows to the table glued.

He stole the milk of hungry kittens,

And walked through doors marked NO ADMITTANCE.

He said he acted thus because

There wasn't any Santa Claus.

Another trick that tickled Jabez

Was crying 'Boo' at little babies.

He brushed his teeth, they said in town,

Sideways instead of up and down.

Yet people pardoned every sin,

And viewed his antics with a grin,

Till they were told by Jabez Dawes,

'There isn't any Santa Claus!'

Deploring how he did behave,

His parents swiftly sought their grave.

They hurried through the portals pearly,

And Jabez left the funeral early.

Like whooping cough, from child to child,

He sped to spread the rumor wild:

'Sure as my name is Jabez Dawes

There isn't any Santa Claus!'

Slunk like a weasel of a marten

Through nursery and kindergarten,

Whispering low to every tot,

'There isn't any, no there's not!'

The children wept all Christmas eve

And Jabez chortled up his sleeve.

No infant dared hang up his stocking

For fear of Jabez' ribald mocking.

He sprawled on his untidy bed,

Fresh malice dancing in his head,

When presently with scalp-a-tingling,

Jabez heard a distant jingling;

He heard the crunch of sleigh and hoof

Crisply alighting on the roof.

What good to rise and bar the door?

A shower of soot was on the floor.

What was beheld by Jabez Dawes?

The fireplace full of Santa Claus!

Then Jabez fell upon his knees

With cries of 'Don't,' and 'Pretty Please.'

He howled, 'I don't know where you read it,

But anyhow, I never said it!'

'Jabez' replied the angry saint,

'It isn't I, it's you that ain't.

Although there is a Santa Claus,

There isn't any Jabez Dawes!'

Said Jabez then with impudent vim,

'Oh, yes there is, and I am him!

Your magic don't scare me, it doesn't'

And suddenly he found he wasn't!

From grimy feet to grimy locks,

Jabez became a Jack-in-the-box,

An ugly toy with springs unsprung,

Forever sticking out his tongue.

The neighbors heard his mournful squeal;

They searched for him, but not with zeal.

No trace was found of Jabez Dawes,

Which led to thunderous applause,

And people drank a loving cup

And went and hung their stockings up.

All you who sneer at Santa Claus,

Beware the fate of Jabez Dawes,

The saucy boy who mocked the saint.

Donner and Blitzen licked off his paint.

Geetha - poem by Oliver Wendell Holmes

A Parody on “A Psalm of Life”

"Life is real, life is earnest,

And the shell is not its pen –

“Egg thou art, and egg remainest”

Was not spoken of the hen.

Art is long and Time is fleeting,

Be our bills then sharpened well,

And not like muffled drums be beating

On the inside of the shell.

In the world’s broad field of battle,

In the great barnyard of life,

Be not like those lazy cattle!

Be a rooster in the strife!

Lives of roosters all remind us,

We can make our lives sublime,

And when roasted, leave behind us,

Hen tracks on the sands of time.

Hen tracks that perhaps another

Chicken drooping in the rain,

Some forlorn and henpecked brother,

When he sees, shall crow again."

Devika – poem by James Thomas Fields (1817 – 1881)

The Owl-Critic

A Lesson to Fault-finders

“WHO stuffed that white owl?” No one spoke in the shop:

The barber was busy, and he couldn’t stop;

The customers, waiting their turns, were all reading

The Daily, the Herald, the Post, little heeding

The young man who blurted out such a blunt question;

Not one raised a head or even made a suggestion;

And the barber kept on shaving.

“Don’t you see, Mister Brown,”

Cried the youth, with a frown,