Ten Famous Romantic Poets

The Romantic movement in Britain in the late 18th century embraced a deep interest in Nature as a source of inspiration for poetry. It emphasised the primacy of the individual's expression of imagination and emotion. Furthermore, it departed from all types of classicism and rebelled against social rules and conventions.

Joanna Baillie (1762-1851) one of the foremost poets of her time

While the names on everybody’s lips are those of Keats, Shelley, Byron, Wordsworth, and Coleridge, there were female poets too in abundance during the Romantic period. Women such as Joanna Baillie, Anna Letitia Barbauld, Felicia Hemans, Letitia Elizabeth Landon, Mary Robinson, Anna Seward, Charlotte Smith, and Mary Tighe were respected and widely read practitioners of the art of poetry. Hemans was a bestselling author of the nineteenth century, and Baillie, the foremost playwright of her time.

Charlotte Turner Smith (1749 - 1806), Romantic poet and novelist

The Romantic Poets were a varied lot. Wordsworth, you might call almost an establishment figure with his sober ways and accession to Laureate status. Blake was a mystic and deeply religious thinker, though inimical to established religion and its pomps. Shelley was a free-thinking poet and pamphleteer who even got rusticated from Oxford University for an essay The Necessity of Atheism. Dying young was the common fate of several Romantic poets: Keats, Shelley and Byron, but like other geniuses they accomplished incandescent work by their early twenties. Because Wordsworth and Coleridge wrote a radical essay to preface their joint collection called Lyrical Ballads, they are considered the theorists and elder statesmen of the Romantic era. However, the letters of Keats can also be mined for a deep understanding of his insights into poetry and the creative process. So too Shelley's seminal essay A Defence of Poetry lays out the dominant role of poetry in language and how poetry enables the mind to realise “a thousand unapprehended combinations of thought.”

Shoba

Devika

Zakia

KumKum

The number of readers selecting a poet was distributed as follows: Wordsworth (3), Blake (2), Shelley (2), Keats (2), and one each for Charlotte Smith, Joanna Baillie, Byron, John Clare, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Alexander Pushkin, to make 15 readers in all – a record number for our Poetry readings.

Talitha

And did those feet in ancient time is a poem by William Blake from the preface to his epic Milton: A Poem in Two Books, one of a collection of writings known as the Prophetic Books.

The preface to Milton, as it appeared in Blake's own illuminated version

Today the poem is known by the corresponding hymn Jerusalem, whose music was written by Sir Hubert Parry in 1916. The orchestration by Sir Edward Elgar is famous. It is an unofficial national anthem which has been sung on quite a few occasions.

The story goes that several musicians were lunching together and spoke of these verses, when the suggestion was made to Hubert Parry to set them to music. “I have frequently thought of doing so,” was the reply, “something like this” — and on the back of a menu he sketched a few bars. It was agreed that they were magnificent; the composition was refined, completed and published. No royalty was exacted, and for fourpence the music was made available. During the WWII the hymn was constantly heard in churches and at public gatherings sung to revive flagging spirits. Here are two verses:

Bring me my Bow of burning gold:

Bring me my arrows of desire:

Bring me my Spear: O clouds unfold!

Bring me my Chariot of fire!

I will not cease from Mental Fight,

Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand:

Till we have built Jerusalem,

In Englands green & pleasant Land.

Talitha pointed out that the poem starts with four questions;

1. Did those feet walk upon England’s mountains green?

2. Was the holy Lamb seen on England’s pleasant pastures?

3. Did the Countenance Divine, shine on our clouded place?

4. (and this is the most interesting one) Was Jerusalem built among these dark Satanic Mills?

Jerusalem represents a holy place, a place of peace and prosperity for all. While these are rhetorical questions, they are asked against the backdrop of a legend that when Jesus was young he travelled to England with his uncle (?) Joseph of Arimathea. Blake is stating that Jerusalem was not here among these “dark Satanic Mills”, a phrase that has acquired a pejorative weight of its own in the light of what the Industrial Revolution did to despoil the countryside, ruin the environment, and make conditions terrible for factory workers.

Blake is now regarded as one of the most original among the early Romantic poets, but in his lifetime he was generally judged as mad. He had visions from childhood, seeing God at age four, and the prophet Ezekiel among some trees in a field. He saw angels with wings bespangling the trees in his garden. Blake said everyone has visions but most have forgotten how to access them (cf. Wordsworth).

“I see very little of Mr. Blake because most of the time he is in Paradise,” so, his wife confided to a friend. The group broke up in laughter on hearing this:

Talitha said there is another poet called Francis Thompson, who wrote a poem called the Kingdom of God. There are a lot of similarities. He talks about Christ visiting England and walking on the river Thames. The poet is trying to localise the divine person working in his own land, not just in Palestine. Further notes sent by Talitha can be accessed here. Everyone appreciated the thorough analysis of the poem by her, but she did not recite the poem itself ! Gopa mentioned that the PM after WWII, Clement Attlee proclaimed he too wanted to build a new Jerusalem.

The impression is that in the current completely changed multi-ethnic, multi-religious, context the word Jerusalem would not thrill the Brits as a nation. “We are a plural society with citizens with a range of perspectives, and we are a largely non-religious society,” was the statement signed by 50 public figures when a PM of recent times (Cameron) labeled Britain a ‘Christian country.’ He was accused of fostering division.

Gopa

A lovely Apparition, sent

To be a moment's ornament;

It is a very romantic poem in the ordinary sense of the word. It describes his wife-to-be, Mary Hutchinson, in three stanzas. Her attributes that he describes make her an ideal partner. She is also very down-to-earth, blessed with

Endurance, foresight, strength, and skill;

A perfect Woman, nobly planned,

To warn, to comfort, and command;

Gopa lost her connection midway. Her internet connection has been subject to failure several times before; she needs an upgrade! Zakia added this wife of his was really like an angel. Gopa said Wordsworth was very much in love with his wife (but there was a lover, Annette Vallon, and a child, Caroline, born out-of-wedlock before this in Paris, remember?).

Joe mentioned that Wordsworth was in the habit of watching girls on the hills in the countryside on his walks. One remembers The Solitary Reaper whose song he heard and wrote about:

Perhaps the plaintive numbers flow

For old, unhappy, far-off things,

and he then confesses:

The music in my heart I bore,

Long after it was heard no more.

Geetha

This second union proved a very happy one, for in Mary he had an intellectual companion and emotional support amid all the trouble arising from quarrels with his relatives, law suits about his property and his children, and his own highly strung temperament and fragile health. In 1818 he left England for Italy and in 1822 was drowned while sailing across the Bay of Spezia.

Jane Williams, portrait by George Clint

Shelley means to say that the word love is so misused, cheapened and vulgarised, that he hesitates to use it in characterising his relationship to Jane.

The poem consists of two eight-line stanzas, both of which follow a quatrain rhyming pattern, ABABCDCD. Alternating lines of iambic trimeter and iambic dimeter are interspersed. The first eight lines are mostly disdaining, despairing, and rejecting negative things. In the next eight lines Shelley gets into his stride with imagery such as

The desire of the moth for the star;

Of the night for the morrow,

to describe his feelings for Jane, on the warmer side of platonic. “In most of these poems [he wrote for her], Shelley projects his love for Jane in a spiritual and devotional manner.” She welcomed his poetic attention, as which woman would not, if Shelley were the source? Joe said he's sure she was quite thrilled to get this poem. Her husband, Edward, didn’t mind. In a twist of fate Edward was drowned with Shelley in a sudden storm on the Gulf of La Spezia (in the NW corner of Italy, near Genoa) when they were sailing an unseaworthy boat.

Here is Geetha's analysis of the poem.

T.S. Eliot praised the second poem, Music when Soft Voices Die, for its lyrical qualities, pointing out that it possessed ‘a beauty of music and a beauty of content; and because it is clearly and simply expressed, with only two adjectives. [soft, sweet]’ (from T.S. Eliot, Swinburne as a Poet, Selected Essays) But we should remember this appreciation of Shelley came late, following Eliot’s denunciation of him earlier as a poet of one's juvenility:

“ … an enthusiasm for Shelley seems to me also to be an affair of adolescence: for most of us, Shelley has marked an intense period before maturity, but for how many does Shelley remain the companion of age?” (Eliot, The Use of Poetry and the Use of Criticism, p. 89)

It is a poetic fragment, and we don’t know if Shelley intended to rework it or add to it; though written in 1821, it was not published until 1824, two years after Shelley’s sudden death, by Mary Shelley. She categorises this among many of the “Miscellaneous Poems, written on the spur of the occasion, and never retouched, [which] I found among his manuscript books, and have carefully copied: I have subjoined, whenever I have been able, the date of their composition.”

Here is Geetha's analysis of the poem. The second poem Geetha recited is only 8 lines, but they will live forever. The words are written for the lips to caress, which is why nearly every anthology contains this poem. Geetha hoped the readers enjoyed listening, as much as she enjoyed reciting them. Shoba chimed in that they were very beautiful poems – ‘light on the tongue,’ Joe observed.

Thommo

Thommo has a fondness for Coleridge whose famous poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (TROTAM) he recited in school; he still remembers most of it:

It is an ancient Mariner,

And he stoppeth one of three.

'By thy long grey beard and glittering eye,

Now wherefore stopp'st thou me?

Now that last line is more arresting than the modern Millennials’ greeting, Whazzup? Thommo said many of his adventure friends have been on cruises to the Antarctic, and TROTAM is connected with the south Pole, as the Prologue notes:

How a Ship having passed the Line was driven by storms to the cold Country towards the South Pole; and how from thence she made her course to the tropical Latitude of the Great Pacific Ocean; and of the strange things that befell; and in what manner the Ancyent Marinere came back to his own Country.He is always reminded of this poem when these friends of his describe their journey to the South Pole. Like TROTAM, Frost at Midnight is also a long poem by Coleridge. It is excerpted to the size manageable for a KRG recitation.

It’s a lovely poem! Coleridge complains about the stillness on this midnight in the frost:

'Tis calm indeed! so calm, that it disturbs

And vexes meditation with its strange

And extreme silentness.

There’s magic in the ending, among his best lines:

Or if the secret ministry of frost

Shall hang them up in silent icicles,

Quietly shining to the quiet Moon.

Arundhaty

After reading the two sonnets On the Departure of the Nightingale and To Hope, Arundhaty wanted to know what is a Gothic novel, for it is mentioned in her biography that Smith ‘helped establish the conventions of Gothic fiction.’ Saras gave a good explanation. The question is answered with many examples at its wikipedia entry, and Gothic fiction may be thought of as fiction that has threatening mysteries and ancestral curses, and trappings such as hidden passages, strange monsters, and fainting helpless damsels. Indeed the novel we read this year, Frankenstein, is a classic of Gothic fiction; another famous novel is Dracula by Bram Stoker. Gopa gave the example of some of Edgar Allan Poe’s stories.

Devika

Devika decided to skip the biography she had prepared of the poet, having sent it to Joe for inclusion in the blog. She could only read the last two stanzas of the poem, the ending of which is:

Kind was her heart and bright her fame,

And Ahalya was her honour’d name.

Biographhy of Joanna Baillie

Joanna Baillie (1762-1851) © The Hunterian Museum

Joanna Baillie was born in 1762 into a clerical Scottish family with uncles who were scientists. As a young child, Baillie was more concerned with sports than poetry, and didn’t learn to read until age ten when she went to a boarding school in Glasgow. She developed an intense love for nature at an early age.

Her first poem Winter Day, published in 1790. She moved to London along with her brother when he became a physician there. This introduced Baillie to the literary society of the day, and she enjoyed convivial relationships with William Wordsworth and Lord Byron in the capital.

With encouragement from her aunt, also a poet, Baillie began to write poetry and drama. Her first published collection was titled Poems: Wherein it is Attempted to Describe Certain Views of Nature and Rustic Manners.

Her seminal work, Plays on the Passions, came out in 1798, the first of a three-volume series of comedies and tragedies which covered love, hatred, and jealousy. It was published anonymously, with speculation about the author’s identity causing a stir in London. However, Baillie disclosed her identity on the title page of the third edition, published in 1800.

Despite her obvious talents, she was reluctant to publish anything much. Baillie was a far more prolific writer of plays than poems. However, by the time of her death in 1851 at the age of 88, Baillie had achieved a reputation as one of the great female poets of all time.

Joanna Baillie was celebrated by a Google Doodle in 2018 on what would have been her 256th birthday. It shows her dramatic work, Plays on the Passions

In 1849 Baillie published the poem Ahalya Baee for private circulation. The brave queen, Maharani or Rajmata Ahilyabai Holkar, is regarded as one of the wisest and most capable female rulers in Indian history. As a prominent ruler of the Malwa kingdom, she spread the message of dharma and promoted industrialisation in the 18th century. Her husband died young, but she did not commit suttee, quite prevalent in those times. She grew Indore from a small place to a big city. It was chiefly her work, and there are many institutions named after her.

For Joanna Ballie to know all about it was a connection that was a terrific encounter of two women of great worth. Everyone appreciated and KumKum said she would read the whole poem, and Priya chimed in. It is beautiful, throughout the length of its 30-odd pages. You can read it online here: Ahalya Baee, a poem by Mrs. Joanna Baillie

Indore prospered during her 30-year rule from a tiny village it became a flourishing city. Her philanthropy reflected in the construction of several temples, ghats, wells, tanks and rest-houses stretching across the length of her kingdom.

A commemorative stamp was issued in her honour on August 25, 1996, by the Indian government. As a tribute to the ruler, Indore’s domestic airport has been named Devi Ahilyabai Holkar Airport.

For further references to Baillie's work consult:

https://scottishwomenpoets.wordpress.com/poets/nineteenth-century-poets/joanna-baillie-1762-1851/

https://inews.co.uk/culture/books/joanna-baillie-google-doodle-256th-birthday-195958

Geeta

http://www.all-art.org/history1-bible_Blake1.html

What follows is taken from the Encyclopedia Britannica entry. William Blake lived in London. He was an English painter, poet, engraver, and visionary mystic who hand-illustrated many of his published series of lyrical poems beginning with Songs of Innocence ( 1789) and Songs of Experience (1794), the latter including the famous poem Tyger! Tyger! burning bright.

He created a new, simple, and emotionally direct mode of thought and expression in the arts and is now considered to have possessed a mind of outstanding originality and power. Yet he was ignored by the public of his day; poets and designers who knew him called him ‘mad’ because he was single-minded and unworldly; he lived life on the edge of poverty and died in neglect.

Blake’s parents were Nonconformists. He was taught by his mother and read widely even as a boy. He loved to walk alone in the villages outside London

All his life he had a strongly visual mind: whatever he imagined he also saw, and vice versa. He had an eidetic mind – the rare ability to see mental images as though they were suspended outside the head. When Blake talked about his visions, he meant images so vivid that they seemed to fill the outer rather than the inner eye of his mind. His poetry is everywhere charged and lit up with the almost physical presence of these images.

From age ten to fourteen he learnt drawing and engraving. He made friends with an intellectual class of people who were unorthodox, rational, and liberal. They were interested in getting Blake’s poems into print.

He married Catherine Boucher. Blake taught her to read and to write, and also instructed her in draftsmanship. Later, she helped him print the illuminated poetry for which he is remembered today; the couple had no children. Blake made a fair living as an engraver. Blake engraved the texts of his poems printed them and coloured the decorations by hand in Songs of Innocence. The child recounts the pleasures of a life in nature in this series and it is the child who teaches the poet. In Songs of Experience he is trapped and bewildered in the prisons of state and church. He was about thirty-five then.

“The Songs are Blake, Blake throughout. The verses are his; he composed and engraved and illuminated them; he made the ink, and printed and subsequently coloured them. The white paper only he did not make, but he made it immortal.” I quote from Henry McIlhenny who wrote an Introduction to a Descriptive Catalogue Blake’s Works, published when they were exhibited at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Here is the link and you can read the most original biography of Blake in a charmingly written introduction:

https://archive.org/details/williamblakedesc00phil/page/n21/mode/2up

Blake was a revolutionary. When eighteen he was inspired by the American Declaration of Independence. He was twenty-two and present in the rioting crowd when they burnt the Newgate Prison. He sympathised with the French Revolution. He was opposed to private property, and to any established church; he detested war.

He wrote about human and social justice. He identified state and church equally as prisons where their subjects suffered physically and spiritually. Blake was a man of remarkable character and entirely upright in what he said and did.

By 1820 Blake finished his two longest books – Milton and Jerusalem. It’s the vision of an ideal human life. Man must free himself from the conventional authority of family life, hierarchies of seniority, sex, status, and the anxiety to conform. A good society cannot be achieved by social and political reforms alone. There must be universal grace of spirit, a sense of human dignity, and a flow of respect between people, before life can be lived in a way that is true to human nature and the natural world

Blake was not appreciated during his lifetime. He died in London in August 1827, aged 60.

Blake's technique to illustrate his poems in “illuminated writing” was to produce his text and design on a copper plate with an impervious liquid. The plate was then dipped in acid so that the text and design remained in relief. That plate could be used to print on paper, and the final copy would be then hand coloured.

Blake's Ancient of Days, 1794. The ‘Ancient of Days’ is described in Chapter 7 of the Book of Daniel. This image depicts Copy D of the illustration currently held at the British Museum

After experimenting with this method Blake designed the series of plates for the poems entitled Songs of Innocence and dated the title page 1789. Blake continued to experiment with the process of illuminated writing and in 1794 combined the early poems with companion poems entitled Songs of Experience. The title page of the combined set announces that the poems show “the two Contrary States of the Human Soul.” Clearly Blake meant for the two series of poems to be read together.

“There were, indeed, two Blakes: one was the lyric poet of Songs, but as a poet he is only one of a long and glorious succession of singers. As a painter he stands out in the history of English art, without a forerunner, without a rival, and without a successor. He stopped at nothing; he did not hesitate to paint God, the Creator, Jehovah. He interested himself in such subjects as the soul entering the body at birth, or the soul leaving the body at the moment of dissolution. He had the magnificent power of Michelangelo and the delicate wistful beauty of the primitive Italian who takes his name from the angels.” This is an extract from a biography linked above of Blake, which was included in a Catalogue of an exhibition his works selected from collections in the United States, and held at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The poem Geeta chose is called The Garden of Love, and this is the engraved printed version, part of the Songs of Experience:

In the final stanza Blake says:

And I saw it was filled with graves

And tombstones where flowers should be

And priests in black gowns were walking their rounds

And binding with briars my joys and desires

Joe asked if Blake is saying his Garden of Love is choked by men who wear priestly gowns. KumKum thought so and Geeta agreed. All these rules and regulations imposed by the clerics are suffocating people. Joe observed that many critics at that time and later have made a point about his insanity. His visions of God are labelled the mind-wandering of man gone over the edge, simply because most people do not have the gift to ‘see.’ Joe recalled Yeats saying that he preferred the insanity of Blake to the sobriety of many other recognised poets [need a reference for this]. Geeta said Blake did not conform, and if you do not conform the easy way to dismiss a person is to call him ‘mad.’ KumKum said we may not understand everything Blake wrote because we do not participate in his visions, which took him to another plane of understanding. KumKum reiterated the casual comment of Blake’s wife, that Mr Blake dwelt mostly in Paradise – a very accurate assessment.

Joe

The stanzas to be recited are excerpted from Byron’s long poem, published in four cantos over a period of six years from 1812 to 1816. The whole is about 17,000 words long; but Joe read only about 500 words concerning Byron’s daughter Ada, whom he had by Annabella Milbanke. Whatever you may say about Byron as a man, he had a great fondness for Ada.

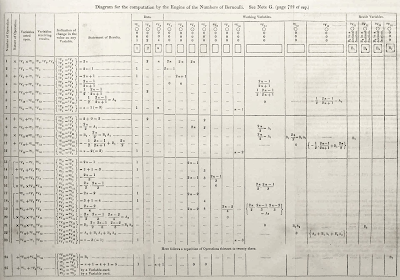

Byron married Annabella in 1815 and Ada was born in 1816, but the couple divorced a short while later. Annabella was mathematically gifted (Byron called her by the joking name Princess of Parallelograms), but her daughter was more than gifted – she was nothing short of brilliant and later in life she met Charles Babbage who invented the Difference Engine (DE), a mechanical calculator with gears and wheels, capable of being programmed to solve difficult mathematical problems by iterating a series of steps, much as electronic computers perform today. It was a brass contraption made of precisely machined gears interlacing with each other in a 3-dimensional array.

The completed portion of Charles Babbage's Difference Engine, 1832. This advanced calculator was intended to produce logarithm tables used in navigation

She became the first person who learned how to code intricate programs for the DE and if you look at them you will appreciate how very mathematically clever she was. She was the world's first computer programmer. That is what she is known for in Computer Science and one of the languages for programming computers was called the ADA language.

Ada Lovelace made this ‘computer’ program to compute the Bernoulli numbers using the Difference Engine of Charles Babbage – the world’s first algorithm

Byron left England in 1816 when Ada was an infant and never saw her again. They say with justification that he was unfaithful to his wife and even dismissive, but the daughter he ever held dear. Though he left her at age 4 months he wrote to her mother and anxiously inquired after his daughter, even writing a poem Fare Thee Well from which here are some stanzas:

And when thou wouldst solace gather,

When our child’s first accents flow,

Wilt thou teach her to say “Father!”

Though his care she must forego?

When her little hands shall press thee,

When her lip to thine is pressed,

Think of him whose prayer shall bless thee,

Think of him thy love had blessed!

Should her lineaments resemble

Those thou never more may’st see,

Then thy heart will softly tremble

With a pulse yet true to me.

CHP is about a world-weary man who travels around Europe, looking for something to distract him from his melancholy. Childe is a precursor title to one who would become a Knight. The stanzas in which the narrative poem is written are called Spenserian stanzas of eight iambic pentameters, followed by single alexandrine (6 iambs), rhymed ABAB BCBC C.

Cantos 1 & 2 were published in 1812 and made Byron a popular poet, the 500 copies printed being sold in 3 days, and ten more editions were published in the next three years. Cantos 3 & 4 were published in 1816 and 1818 respectively. Joe excerpted the stanzas where the poet remembers Ada in the midst of the enthralling scenery as he sails along the Rhine river in Germany and Belgium and sees the castles and the craggy hills along the banks. He remembers Ada and writes about her.

A critic notes “the poem is about the meaning of freedom in all its forms—personal, political, poetic.” Later in life Byron who always fought for the underdog, took up Greece’s fight against Ottoman oppression and it was in the midst of that he lost his life in Missolonghi, Greece at the head of a ragtag band of soldiers in 1824. The immediate cause was probably sepsis from bloodletting for a fever he caught. For the Greeks he became a national hero, deeply mourned.

Byron statue depicting Greece in the form of a woman crowning him in Athens, Greece, outside the National Garden. Sculptors are the Frenchmen Henri-Michel Chapu and Alexandre Falguière

Byron was most unfortunate in never being able to see Ada again. There was another daughter, whom he named Allegra, born by Claire Clairmont, Mary Shelley’s half-sister. He took her away to Switzerland and had her placed in a convent to be looked after by nuns. But she succumbed to typhus at age five.

When Joe finished his reading KumKum said she did not know he was such a wonderful father. This daughter lived to an age and made her mark, and married well, and so on. Saras too regretted he did not see her after she was born – he left when she was only four months old. Arundhaty recognised it was a poem (at least these verses) of longing and desire. Several of the readers approved the reading by saying ‘Very nice!’ and Pamela mentioned that these verses reminded her of her grand-daughter:

To hold thee lightly on a gentle knee,

And print on thy soft cheek a parent’s kiss, –

Kavita

Spring relates to his youthful state of mind. Next is Summer during which the man ruminates and reaches higher. Autumn suggests resignation, and portrays the wiser years of adulthood. Winter represents the ending years and finally death. Keats, Kavita said, was very young, but he was so reflective about life. This is a young person who didn’t have many years to live, yet he could picturise what life could be. A lot of his relationship with nature comes out. He would correlate Nature with the entire course of human life.

Romantics, do that, said, KumKum. Saras also said it was one of the features of Romantic Poetry. He was also not well – suffering from tuberculosis, which he contracted while nursing his brother, Tom. He ultimately died in Rome, where he was advised to go to recuperate in a more healthful climate.

Devika mentioned that Joanna Baillie, the Scottish poet she read, did not go to school until age ten. She was more into Nature and wandering about the woods as a young girl. Saras said women were given little education, most were taught the rudiments at home. KumKum said the Church may have contributed to women’s education. Schooling for girls was confined to the rich otherwise. They used to have governesses, Kavita suggested, but that implied a level of opulence of the parents.

KumKum

John Keats in 1819, painted by his friend Joseph Severn

She insisted she has no bias towards male poets, it’s just that the poems women wrote at the time do not hold a candle to the great Romantic Poets, who are all men. This is the third Ode she was reading at KRG of Keats. She refreshes herself by reading all of them together. Keats’ philosophy is expressed in a beautiful way in these Odes.

This Ode on Melancholy is the shortest one. The first stanza is about melancholy and the tendencies of those who are thus afflicted – some commit suicide, and take to swallowing potions that cause death, if not immediately then inevitably over time. And the death won’t be a happy one, says Keats. In the second stanza Keats advises Nature as a cure for melancholy. The person will get sure relief by spending time without a care in the lap of Nature; the relief may be temporary but it can be repeated:

Then glut thy sorrow on a morning rose,

Or on the rainbow of the salt sand-wave,

The third stanza, loveliest of them, discloses that

Ay, in the very temple of Delight

Veil'd Melancholy has her sovran shrine,

Pleasure and sorrow cannot be long separated. The last two lines are a coda, offering the soothing notion that experiencing this sadness comes with the reward of tasting the highest Joy!

Shoba agreed it was a beautiful poem. KumKum said she wanted to read one more Ode next year – if she was still alive. Many protested against the implied pessimism and asked ‘Why do you say such things?’ Her reply was that Keats taught her hope and expectation, not pessimism. Devika pointed out that Covid can happen to anybody, it has little to do with being old. Age is a number and when the number comes up, you go, said Devika. Arundhaty wondered if reading Keats made KumKum melancholic also!

Joe took two lessons from Keats. The first is start young, no matter what you are going to do, there is never an age when you are too young to start doing it. The second is BE PROLIFIC! Fill the time with the works of your hand or mind, and never cease to brim with ideas for works. Keats was so steeped in Poetry that as he walked he would be composing and might have tossed off a sonnet at the end of ten minutes. He wrote sixty-four sonnets in all. He was eighteen years old when he composed his first sonnet in 1814; he was turning twenty-four when he completed his last one.

KumKum again spoke of her Keats devotion, having followed him for a long time and having all sorts of books by him and about him. She hopes Joe has not given them away. He was twenty-five when he died. KumKum went on to blame some ‘stupid girl’ for his death, (did she mean Fanny Brawne for whom he wrote this thrilling sonnet?). This is as bizarre as Byron’s charge that the critics killed him. His letters set forth not only his humanity but his constant thinking on the art of Poesy, and awareness of his method; for instance, he writes in a letter to his brother George in Sept 1819:

You speak of Lord Byron and me – There is this great difference between us. He describes what he sees – I describe what I imagine – mine is the hardest.

KumKum once again referred to Kavita's remark that at such a young age Keats had a vision of his whole life. Feeling that her choice and staunch advocacy of Keats required yet another apology she said she is not against women poets, but among Romantic Poets the men are ‘something else.’

Pamela

I bring fresh showers for the thirsting flowers,

From the seas and the streams;

I bear light shade for the leaves when laid

In their noonday dreams.

...

I am the daughter of Earth and Water,

And the nursling of the Sky;

I pass through the pores of the ocean and shores;

I change, but I cannot die.

He was the son of an influential MP, Timothy Shelley, and had four younger brothers and a sister. He went to Eton for schooling in 1804 and was badly bullied. He entered Oxford in 1810 and is not known to have attended many lectures but his reading was ceaseless. He began writing poetry, but his first publication was a Gothic novel.

In 1811, Shelley anonymously published a pamphlet called The Necessity of Atheism. His refusal to repudiate the authorship of the pamphlet resulted in his expulsion from Oxford. He was in a parlous condition financially for two years. At the age of nineteen he eloped to Scotland with Harriet Westbrook. Once married he moved to the Lake District of England to study and write.

He was unhappy with Harriet. He then eloped once again, with Mary Shelley in 1816 when she was only sixteen years old. During their later association with Lord Byron during a trip to Switzerland, Mary Shelley was inspired to write the classic Frankenstein.

Adonais, an Elegy on the Death of John Keats, was written as a pastoral elegy by Shelley for John Keats in 1821; it is one of his best and most well-known works. Pamela recited as much of the poem as she felt she could manage in the time, the first three stanzas and the last two of the 55-stanza long poem which begins:

I weep for Adonais—he is dead!

Oh, weep for Adonais! though our tears

Thaw not the frost which binds so dear a head!

and ends with Shelley's lament:

I am borne darkly, fearfully, afar;

Whilst, burning through the inmost veil of Heaven,

The soul of Adonais, like a star,

Beacons from the abode where the Eternal are.

He is lamenting for a colleague, said KumKum. Shelley felt the tragedy of Keats’ death with a keenness that transcended the friendship they shared with common friends in London. He himself was to be taken only a year later. Both are buried in the Protestant cemetery in Rome, their graves quite close, and in their joint memory was created the Keats-Shelley Memorial House, hard by the Spanish Steps in Rome:

Keats-Shelley Memorial House in Rome

In a two-room-apartment in this house John Keats, who was dying of tuberculosis, lived after arriving in Rome in November 1820. Friends and doctors who hoped that the warmer climate might improve his health urged him to go to Italy. He was accompanied by the artist Joseph Severn, who nursed and looked after Keats tenderly until his death at age twenty-five on 23 February 1821, in this house.

Saras & Priya

William Wordsworth (1770-1850), along with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, launched the Romantic Age in English Literature, with the publication of Lyrical Ballads in 1798. His magnum opus was The Prelude, a semi autobiographical poem that he worked on, revised and expanded throughout his life and was published posthumously by his wife. He was Poet Laureate from 1843 till his death in 1850; interestingly he did not write a single official verse for royal occasions during his laureateship.

He was not close to his father, who however encouraged Wordsworth in his reading. William was required to memorise large portions of verse from Milton and Shakespeare. His early education was indifferent. Upon his mother’s death in 1778 he was sent to Hawkshead Grammar School in Lancashire and later in 1787 he began attending St. John’s College in Cambridge.

He was a nature lover, often going for long walks, visiting places famous for the beauty of their landscape. He also walked through many European countries. He sympathised with the revolution in France, however he had a change of heart after witnessing its brutality. While in France he met John “Walker” Stewart who was nearing the end of his thirty years of wandering on foot from Madras, India through Persia, Arabia, Europe, and on to the fledgling United States. Stewart Published his philosophy in a book entitled The Apocalypse of Nature (1791) which might have influenced some of Wordsworth's works.

Wordsworth made his debut as a poet in 1787, the year he joined Cambridge when he published a sonnet in the European Magazine. He met Coleridge in 1795 and became his close friend. In 1797, Wordsworth along with his sister Dorothy, who was his constant companion in life, moved to Somerset close to Coleridge's home and their collaboration produced the vastly influential Lyrical Ballads. This collection included Tintern Abbey one of his most famous poems and Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner. In the preface of the 1802 edition of the collection Wordsworth discusses the elements of a new type of verse – based on the ordinary language “really used by men.” He also defines poetry as “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility,” a definition still used.

In 1799 Wordsworth and Dorothy went on a walking tour of the Lake district and decided to settle down there, this time close to Robert Southey. Wordsworth, Coleridge and Southey came to be known as the Lake poets.

In 1802 he married his childhood friend, Mary Hutchinson. His sister continued to live with them and became close friends with Mary.

He continued writing throughout his life and enjoyed considerable success. In his later life, however, the deaths of close friends made him depressed till finally in 1847, after the death of his daughter at the age of 42, he gave up writing altogether. He was then aged 77 and had three years more to live.

Both Saras and Priya chose the same poem by Wordsworth and read excerpts from it, the full name of which must be one of the longest names ever given to a poem:

Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey, On Revisiting the Banks of the Wye during a Tour. July 13, 1798.

Wordsworth was very fond of going on these walking tours. He walked all over England and large parts of Europe. This abbey was actually a ruin, an abbey that had been abandoned after Henry VIII had proscribed the Roman Catholic Church. The abbey itself does not feature in the poem, and is not mentioned anywhere in the poem.

Tintern Abbey, founded in 1131, fell into ruin after the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 16th century

He talks about the area surrounding the monastery. He mentions at the beginning visiting this section of the Welsh Border five years earlier in 1793 when he was twenty-three.

Wordsworth claimed to have composed the poem entirely in his head, jotting it down only when he reached Bristol, a distance of some 22 miles. This probably represented a day’s journey in those days.

The poem is written in decasyllabic blank verse consisting of verse paragraphs rather than stanzas. It contains elements of both ode and dramatic monologue and is now designated as a conversation poem.

It has been criticised in more modern times for whitewashing the very Nature that he was writing about. Wales had begun to be industrialised, fuelled by Napoleonic Wars and the American Revolution and the “wreaths of smoke” may have been rising from the mines, not from cottage chimneys.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/wales/history/sites/themes/guide/ch15_industrial_revolution.shtml

... wreaths of smoke

Sent up, in silence, from among the trees!

arose not from fires burning in the hearths of homes, but smoke from factories. A bit of a whitewash. Later, he writes:

For nature then

...

To me was all in all.

It is the crux of the poem, said Priya.

‘It’s beautiful, it’s really beautiful,’ Zakia exclaimed when Priya ended with Wordsworth's elevated thoughts on Nature:

And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man:

...

well pleased to recognise

In nature and the language of the sense

The anchor of my purest thoughts, the nurse,

The guide, the guardian of my heart, and soul

Of all my moral being.

Arundhaty has the opportunity to travel periodically to the Nilgiri forests where her daughter Shubhra lives close to Nature, and hears the thrush singing daily – an apt reminder of the joy that the Romantic poets extolled, said Priya.

Shoba

John Clare by William Hilton,

oil on canvas, 1820

Clare’s education at a church school ended at age eleven. He was mostly self taught. He worked as a farm labourer and a lime lighter (a lime light is a type of lamp in which white light is produced by heating lime, calcium oxide, to white heat with a gas flame).

He was small built, only five feet tall, having suffered from malnutrition when young. He suffered ill health and poverty, struggling to support his wife and six children. After some early success, he went through a lean period when two of his books were not successful. But in the poems written later in life, he developed a very distinctive voice, an intensity and vibrancy.

Only in the late twentieth century has John Clare been acknowledged as one among the major poets of his time.

Shoba read the first poem, I Am, which is self-reflecting and insightful, even though it speaks of being alone:

I am the self-consumer of my woes—

They rise and vanish in oblivious host,

Like shadows in love’s frenzied stifled throes

And yet I am, and live—like vapours tossed

And the last two lines:

Untroubling and untroubled where I lie

The grass below—above, the vaulted sky.

It is said he wrote this poem while an inmate at the asylum in later years. A patron supported him financially and the doctor who looked after him encouraged his poetry.

Even Keats’ education was limited though he became a surgeon's assistant. Priya asked Shoba, and she confirmed that Clare went to a church school only till the age of eleven. In Malayalam we say ‘pallikoodam’ and that means church school literally, because in earlier times schools were connected to the church; although the word has now come to signify simply a school. The most famous modern Pallikoodam is that started by Mary Roy:

https://www.pallikoodam.org/

Zakia

Alexander S. Pushkin (1799-1837). Copy of Portrait after V. Tropinin, 1827. Found in the collection of the Goethe Museum Düsseldorf

Alexander Pushkin was born into one of Russia’s most famous noble families. His mother was the granddaughter of an Abyssinian prince, Hannibal, who had been a favourite of Peter I, and many of Pushkin’s forebears played important roles in Russian history. Pushkin began writing poetry as a student at the Lyceum at Tsarskoe Selo, a school for aristocratic youth in St. Petersburg.

His most famous poems are decidedly Romantic in their celebration of freedom and defence of personal liberty, but his concise, moderate, and spare style has proven difficult for many critics to categorise. His many narrative poems, epics, and lyrics are the mainstays of the Russian literary tradition and are widely recalled in a country well-known for ordinary people memorising reams of poetry. His works have inspired countless song cycles, ballets, and other artistic interpretations.

At the end 1823, Pushkin began work on his masterpiece, Evgeny Onegin pronounced thus, in English written as Eugene Onegin. Written over seven years, the poem was published in full in 1833. In it, Pushkin invented a new stanza: iambic tetrameter with alternating feminine and masculine rhymes.

Alexander Pushkin – On 6 June 1880, on his 81st Anniversary, Russia paid tribute to its great poet by unveiling the iconic Pushkin Monument in Moscow

In 1880, a statue of Pushkin was unveiled in Moscow, to speeches given by Dostoevsky and Turgenev, who claimed that the statue allowed Russians to claim themselves as a great nation “because this nation has given birth to such a man.” You can read more about Pushkin at the Wikipedia site.

Zakia shared a quote by Pushkin:

In our own time the most successful and magical use of the Onegin stanza was by Vikram Seth, when he told contemporary tales of California entirely in Onegin sonnets! The Golden Gate (TGG) is a marvellous work, light in touch throughout, but with alternating moods of story-telling, reflection and pondering human woe. Since this is a reading of Romantic Poets one may be permitted to introduce a modern who drew inspiration from Nature. Here's Sonnet 12.5 from TGG:

It’s spring! Melodious and fragrant

Pear blossoms bloom and blanch the trees,

While pink and ravishing and fragrant

Qunice burst in shameless colonies

On woody bushes, and the slender

Yellow oxalis, brief and tender,

Brilliant as mustard, sheets the ground,

And blue jays croak, and all around

Iris and daffodil are sprouting

With such assurance that the shy

Grape hyacinth escapes the eye,

And spathes of Easter lilies, flouting

Nomenclature, now effloresce

In white and Lenten loveliness.

The second poem Awakening ends in a Keatsian wish ‘half in love with easeful death’ ––

O love, O love,

Listen to my prayers,

Send me again

Your sweet visions,

And in the morning

Let me die

In ecstasy

With no awakening.

I long for a decent translation into the language of desire and longing, which in India is Urdu. Till then this will serve as a place-holder:

Urdu Version 1 of Pushkin poem:

ए मेहबूबा, ए सकी

मेरी दुआ सुनो

मुझे दुबारा भेज दो

तेरी दिलकश नज़रें

और सुबह के वक़्त

मुझे मरने दो

सरमस्ती में

बगैर किसी बेदारी के

Urdu Version 2 of Pushkin poem:

मेहबूबा, मेरे दुआ सुनो

तेरी दिलकश नज़रें फिर भेजो

ताक़ि सुबह मर जाऊं

ख़ुशी से, बिना एहसास पाऊं !

I am thankful to friends of Pamela who did the translation, which I have somewhat modified. The session ended with an equally soulful poem, I loved you, by Pushkin in which a man lets go of a hopeless love; this too deserves to be translated into Urdu.

The readers closed with the thought that after this coronavirus trouble is over we have to celebrate KumKum's 80th birthday.

The Poems

1. Talitha

Jerusalem ["And did those feet in ancient time"] by William Blake

And did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon Englands mountains green:

And was the holy Lamb of God,

On Englands pleasant pastures seen!

And did the Countenance Divine,

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here,

Among these dark Satanic Mills?

Bring me my Bow of burning gold:

Bring me my arrows of desire:

Bring me my Spear: O clouds unfold!

Bring me my Chariot of fire!

I will not cease from Mental Fight,

Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand:

Till we have built Jerusalem,

In Englands green & pleasant Land.

2. Arundhaty

Elegiac Sonnets - VI &VII by Charlotte Smith

SONNET VI. To Hope.

OH, Hope! thou soother sweet of human woes!

How shall I lure thee to my haunts forlorn!

For me wilt thou renew the wither'd rose,

And clear my painful path of pointed thorn?

Ah come, sweet nymph! in smiles and softness drest,

Like the young hours that lead the tender year;

Enchantress come! and charm my cares to rest:—

Alas! the flatterer flies, and will not hear!

A prey to fear, anxiety and pain,

Must I a sad existence still deplore?

Lo!—the flow’rs fade, but all the thorns remain,

`For me the vernal garland blooms no more.'

Come then `pale Misery's love!' be thou my cure,

And I will bless thee, who tho' slow art sure.

SONNET VII. On the Departure of the Nightingale.

SWEET poet of the woods—a long adieu!

Farewell, soft minstrel of the early year!

Ah! 'twill be long ere thou shalt sing anew,

And pour thy music on the `night's dull ear.'

Whether on Spring thy wandering flights await,

Or whether silent in our groves you dwell,

The pensive muse shall own thee for her mate,

And still protect the song the loves so well.

With cautious step the lovelorn youth shall glide

Thro’ the lone brake that shades thy mossy nest;

And shepherd girls, from eyes profane shall hide

The gentle bird, who sings of pity best:

For still thy voice shall soft affections move,

And still be dear to sorrow, and to love!

3. Devika

Ahalya Baee by Joanna Baillie

For thirty years – her reign of peace –,

The land in blessing did increase;

And she was blessed by every tongue,

By stern and gentle, old and young.

And where her works of love remain,

On mountain pass, on hill or plain,

There stops the traveller a while.

And eyes it with a mournful smile,

With muttr’ing lips, that seem to say,

“This was the work of Ahalya Baee.”

The learned Sage, who loves to muse,

And many a linked thought pursues,

Says to himself, and heaves a sigh

For things to come and things gone by,

“O that our restless chiefs, by misr’y school'd,

Would rule their states as that brave woman rul’d !”

Yea, even the children at their mother's feet

Are taught such homely rhyming to repeat

“In latter days from Brahma came,

To rule our land, a noble Dame,

Kind was her heart and bright her fame,

And Ahalya was her honour’d name.”

[https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t8df6rh1s&view=1up&seq=1]

4. Geeta

The Garden of Love by William Blake

I went to the Garden of Love,

And saw what I never had seen:

A Chapel was built in the midst,

Where I used to play on the green.

And the gates of this Chapel were shut,

And Thou shalt not. writ over the door;

So I turn'd to the Garden of Love,

That so many sweet flowers bore.

And I saw it was filled with graves,

And tomb-stones where flowers should be:

And Priests in black gowns, were walking their rounds,

And binding with briars, my joys & desires.

Alternate 5-stanza version recited by Geeta:

I laid me down upon a bank

Where Love lay sleeping

I heard among the rushes dank

Weeping, weeping

Then I went to the heath and the wild

To the thistles and thorns of the waste

And they told me how they were beguiled

Driven out, and compelled to the chaste

I went to the Garden of Love

And saw what I never had seen

A Chapel was built in the midst

Where I used to play on the green

And the gates of this Chapel were shut

And "Thou shalt not," writ over the door

So I turned to the Garden of Love

That so many sweet flowers bore

And I saw it was filled with graves

And tombstones where flowers should be

And priests in black gowns were walking their rounds

And binding with briars my joys and desires.

5. Geetha – two poems by Percy Bysshe Shelley

To ----

One word is too often profaned

For me to profane it,

One feeling too falsely disdained

For thee to disdain it;

One hope is too like despair

For prudence to smother,

And pity from thee more dear

Than that from another.

I can give not what men call love,

But wilt thou accept not

The worship the heart lifts above

And the Heavens reject not,—

The desire of the moth for the star,

Of the night for the morrow,

The devotion to something afar

From the sphere of our sorrow?

Music when Soft Voices Die (To --)

Music, when soft voices die,

Vibrates in the memory—

Odours, when sweet violets sicken,

Live within the sense they quicken.

Rose leaves, when the rose is dead,

Are heaped for the belovèd’s bed;

And so thy thoughts, when thou art gone,

Love itself shall slumber on.

6. Gopa

She Was a Phantom of Delight by William Wordsworth

She was a Phantom of delight

When first she gleamed upon my sight;

A lovely Apparition, sent

To be a moment's ornament;

Her eyes as stars of Twilight fair;

Like Twilight's, too, her dusky hair;

But all things else about her drawn

From May-time and the cheerful Dawn;

A dancing Shape, an Image gay,

To haunt, to startle, and way-lay.

I saw her upon nearer view,

A Spirit, yet a Woman too!

Her household motions light and free,

And steps of virgin-liberty;

A countenance in which did meet

Sweet records, promises as sweet;

A Creature not too bright or good

For human nature's daily food;

For transient sorrows, simple wiles,

Praise, blame, love, kisses, tears, and smiles.

And now I see with eye serene

The very pulse of the machine;

A Being breathing thoughtful breath,

A Traveller between life and death;

The reason firm, the temperate will,

Endurance, foresight, strength, and skill;

A perfect Woman, nobly planned,

To warn, to comfort, and command;

And yet a Spirit still, and bright

With something of angelic light.

7. Joe

Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage by Lord Byron

From Canto 3, a few verses concerning his daughter Ada

I

Is thy face like thy mother's, my fair child!

ADA! sole daughter of my house and heart?

When last I saw thy young blue eyes they smiled,

And then we parted, -- not as now we part,

But with a hope. --

Awaking with a start,

The waters heave around me; and on high

The winds lift up their voices: I depart,

Whither I know not; but the hour's gone by,

When Albion's lessening shores could grieve or glad mine eye.

…

LV

And there was one soft breast, as hath been said,

Which unto his was bound by stronger ties

Than the church links withal; and, though unwed,

That love was pure, and, far above disguise,

Had stood the test of mortal enmities

Still undivided, and cemented more

By peril, dreaded most in female eyes;

But this was firm, and from a foreign shore

Well to that heart might his these absent greetings pour!

…

I send the lilies given to me;

Though long before thy hand they touch,

I know that they must wither'd be,

But yet reject them not as such;

For I have cherish'd them as dear,

Because they yet may meet thine eye,

And guide thy soul to mine even here,

When thou behold’st them drooping nigh,

And know’st them gather'd by the Rhine,

And offer'd from my heart to thine!

…

CXV

(About Ada Lovelace)

My daughter! with thy name this song begun --

My daughter! with thy name thus much shall end --

I see thee not, -- I hear thee not, -- but none

Can be so wrapt in thee: thou art the friend

To whom the shadows of far years extend:

Albeit my brow thou never should’st behold,

My voice shall with thy future visions blend

And reach into thy heart, -- when mine is cold, --

A token and a tone, even from thy father's mould.

CXVI

To aid thy mind’s development, -- to watch

Thy dawn of little joys, -- to sit and see

Almost thy very growth, -- to view thee catch

Knowledge of objects, -- wonders yet to thee!

To hold thee lightly on a gentle knee,

And print on thy soft cheek a parent’s kiss, --

This, it should seem, was not reserved for me;

Yet this was in my nature: as it is,

I know not what is there, yet something like to this.

…

CXVIII

The child of love, -- though born in bitterness

And nurtured in convulsion. Of thy sire

These were the elements, -- and thine no less

As yet such are around thee, -- but thy fire

Shall be more temper’d and thy hope far higher.

Sweet be thy cradled slumbers! O’er the sea,

And from the mountains where I now respire,

Fain would I waft such blessing upon thee,

As, with a sigh, I deem thou might’st have been to me!

8. Kavita

Human Seasons by John Keats

Four Seasons fill the measure of the year;

There are four seasons in the mind of man:

He has his lusty Spring, when fancy clear

Takes in all beauty with an easy span:

He has his Summer, when luxuriously

Spring's honied cud of youthful thought he loves

To ruminate, and by such dreaming high

Is nearest unto heaven: quiet coves

His soul has in its Autumn, when his wings

He furleth close; contented so to look

On mists in idleness—to let fair things

Pass by unheeded as a threshold brook.

He has his Winter too of pale misfeature,

Or else he would forego his mortal nature.

9. KumKum

Ode on Melancholy by John Keats

No, no, go not to Lethe, neither twist

Wolf's-bane, tight-rooted, for its poisonous wine;

Nor suffer thy pale forehead to be kiss'd

By nightshade, ruby grape of Proserpine;

Make not your rosary of yew-berries,

Nor let the beetle, nor the death-moth be

Your mournful Psyche, nor the downy owl

A partner in your sorrow's mysteries;

For shade to shade will come too drowsily,

And drown the wakeful anguish of the soul.

But when the melancholy fit shall fall

Sudden from heaven like a weeping cloud,

That fosters the droop-headed flowers all,

And hides the green hill in an April shroud;

Then glut thy sorrow on a morning rose,

Or on the rainbow of the salt sand-wave,

Or on the wealth of globed peonies;

Or if thy mistress some rich anger shows,

Emprison her soft hand, and let her rave,

And feed deep, deep upon her peerless eyes.

She dwells with Beauty—Beauty that must die;

And Joy, whose hand is ever at his lips

Bidding adieu; and aching Pleasure nigh,

Turning to poison while the bee-mouth sips:

Ay, in the very temple of Delight

Veil'd Melancholy has her sovran shrine,

Though seen of none save him whose strenuous tongue

Can burst Joy's grape against his palate fine;

His soul shalt taste the sadness of her might,

And be among her cloudy trophies hung.

10. Pamela

Adonais by P.B.Shelley. First 3 and last 2 stanzas.

I

I weep for Adonais—he is dead!

Oh, weep for Adonais! though our tears

Thaw not the frost which binds so dear a head!

And thou, sad Hour, selected from all years

To mourn our loss, rouse thy obscure compeers,

And teach them thine own sorrow, say: "With me

Died Adonais; till the Future dares

Forget the Past, his fate and fame shall be

An echo and a light unto eternity!"

II

Where wert thou, mighty Mother, when he lay,

When thy Son lay, pierc’d by the shaft which flies

In darkness? where was lorn Urania

When Adonais died? With veiled eyes,

'Mid listening Echoes, in her Paradise

She sate, while one, with soft enamour'd breath,

Rekindled all the fading melodies,

With which, like flowers that mock the corse beneath,

He had adorn'd and hid the coming bulk of Death.

III

Oh, weep for Adonais—he is dead!

Wake, melancholy Mother, wake and weep!

Yet wherefore? Quench within their burning bed

Thy fiery tears, and let thy loud heart keep

Like his, a mute and uncomplaining sleep;

For he is gone, where all things wise and fair

Descend—oh, dream not that the amorous Deep

Will yet restore him to the vital air;

Death feeds on his mute voice, and laughs at our despair.

…

LIV

That Light whose smile kindles the Universe,

That Beauty in which all things work and move,

That Benediction which the eclipsing Curse

Of birth can quench not, that sustaining Love

Which through the web of being blindly wove

By man and beast and earth and air and sea,

Burns bright or dim, as each are mirrors of

The fire for which all thirst; now beams on me,

Consuming the last clouds of cold mortality.

LV

The breath whose might I have invok’d in song

Descends on me; my spirit's bark is driven,

Far from the shore, far from the trembling throng

Whose sails were never to the tempest given;

The massy earth and sphered skies are riven!

I am borne darkly, fearfully, afar;

Whilst, burning through the inmost veil of Heaven,

The soul of Adonais, like a star,

Beacons from the abode where the Eternal are.

11. & 12. Priya & Saras

Excerpts from Tintern Abbey by Wordsworth

1.

Five years have past; five summers, with the length

Of five long winters! and again I hear

These waters, rolling from their mountain-springs

With a soft inland murmur.—Once again

Do I behold these steep and lofty cliffs,

That on a wild secluded scene impress

Thoughts of more deep seclusion; and connect

The landscape with the quiet of the sky.

The day is come when I again repose

Here, under this dark sycamore, and view

These plots of cottage-ground, these orchard-tufts,

Which at this season, with their unripe fruits,

Are clad in one green hue, and lose themselves

'Mid groves and copses. Once again I see

These hedge-rows, hardly hedge-rows, little lines

Of sportive wood run wild: these pastoral farms,

Green to the very door; and wreaths of smoke

Sent up, in silence, from among the trees!

With some uncertain notice, as might seem

Of vagrant dwellers in the houseless woods,

Or of some Hermit's cave, where by his fire

The Hermit sits alone.

(omitting stanza 2)

......

3. oh! how oft—

In darkness and amid the many shapes

Of joyless daylight; when the fretful stir

Unprofitable, and the fever of the world,

Have hung upon the beatings of my heart—

How oft, in spirit, have I turned to thee,

O sylvan Wye! thou wanderer thro’ the woods,

How often has my spirit turned to thee!

And now, with gleams of half-extinguished thought,

With many recognitions dim and faint,

And somewhat of a sad perplexity,

The picture of the mind revives again:

While here I stand, not only with the sense

Of present pleasure, but with pleasing thoughts

That in this moment there is life and food

For future years. And so I dare to hope,

Though changed, no doubt, from what I was when first

I came among these hills; when like a roe

I bounded o'er the mountains, by the sides

Of the deep rivers, and the lonely streams,

Wherever nature led: more like a man

Flying from something that he dreads, than one

Who sought the thing he loved. For nature then

(The coarser pleasures of my boyish days

And their glad animal movements all gone by)

To me was all in all.—I cannot paint

What then I was. The sounding cataract

Haunted me like a passion: the tall rock,

The mountain, and the deep and gloomy wood,

Their colours and their forms, were then to me

An appetite; a feeling and a love,

That had no need of a remoter charm,

By thought supplied, nor any interest

Unborrowed from the eye.—That time is past,

And all its aching joys are now no more,

And all its dizzy raptures. Not for this

Faint I, nor mourn nor murmur; other gifts

Have followed; for such loss, I would believe,

Abundant recompense. For I have learned

To look on nature, not as in the hour

Of thoughtless youth; but hearing oftentimes

The still sad music of humanity,

Nor harsh nor grating, though of ample power

To chasten and subdue.—And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man:

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all things. Therefore am I still

A lover of the meadows and the woods

And mountains; and of all that we behold

From this green earth; of all the mighty world

Of eye, and ear,—both what they half create,

And what perceive; well pleased to recognise

In nature and the language of the sense

The anchor of my purest thoughts, the nurse,

The guide, the guardian of my heart, and soul

Of all my moral being.

(skipping the rest)

13. Shoba two poems by John Clare

I Am!

I am—yet what I am none cares or knows;

My friends forsake me like a memory lost:

I am the self-consumer of my woes—

They rise and vanish in oblivious host,

Like shadows in love’s frenzied stifled throes

And yet I am, and live—like vapours tossed

Into the nothingness of scorn and noise,

Into the living sea of waking dreams,

Where there is neither sense of life or joys,

But the vast shipwreck of my life’s esteems;

Even the dearest that I loved the best

Are strange—nay, rather, stranger than the rest.

I long for scenes where man hath never trod

A place where woman never smiled or wept

There to abide with my Creator, God,

And sleep as I in childhood sweetly slept,

Untroubling and untroubled where I lie

The grass below—above the vaulted sky.

Little Trotty Wagtail

Little trotty wagtail, he went in the rain,

And tittering, tottering sideways he near got straight again.

He stooped to get a worm, and look’d up to catch a fly,

And then he flew away ere his feathers they were dry.

Little trotty wagtail, he waddled in the mud,

And left his little footmarks, trample where he would.

He waddled in the water-pudge, and waggle went his tail,

And chirrupt up his wings to dry upon the garden rail.

Little trotty wagtail, you nimble all about,

And in the dimpling water-pudge you waddle in and out;

Your home is nigh at hand, and in the warm pigsty,

So little Master Wagtail, I’ll bid you a goodbye.

14. Thommo

Frost at Midnight by Samuel Taylor Coleridge (abridged)

The Frost performs its secret ministry,

Unhelped by any wind. The owlet's cry

Came loud—and hark, again! loud as before.

The inmates of my cottage, all at rest,

Have left me to that solitude, which suits

Abstruser musings: save that at my side

My cradled infant slumbers peacefully.

'Tis calm indeed! so calm, that it disturbs

And vexes meditation with its strange

And extreme silentness. Sea, hill, and wood,

This populous village! Sea, and hill, and wood,

With all the numberless goings-on of life,

Inaudible as dreams! the thin blue flame

Lies on my low-burnt fire, and quivers not;

Only that film, which fluttered on the grate,

Still flutters there, the sole unquiet thing.

Methinks, its motion in this hush of nature

Gives it dim sympathies with me who live,

Making it a companionable form,

Whose puny flaps and freaks the idling Spirit

By its own moods interprets, every where

Echo or mirror seeking of itself,

And makes a toy of Thought.

But O! how oft,

How oft, at school, with most believing mind,

Presageful, have I gazed upon the bars,

To watch that fluttering stranger ! and as oft

With unclosed lids, already had I dreamt

Of my sweet birth-place, and the old church-tower,

Whose bells, the poor man's only music, rang

…

But thou, my babe! shalt wander like a breeze

By lakes and sandy shores, beneath the crags

Of ancient mountain, and beneath the clouds,

Which image in their bulk both lakes and shores

And mountain crags: so shalt thou see and hear

The lovely shapes and sounds intelligible

Of that eternal language, which thy God

Utters, who from eternity doth teach

Himself in all, and all things in himself.

Great universal Teacher! he shall mould

Thy spirit, and by giving make it ask.

Therefore all seasons shall be sweet to thee,

Whether the summer clothe the general earth

With greenness, or the redbreast sit and sing

Betwixt the tufts of snow on the bare branch

Of mossy apple-tree, while the night-thatch

Smokes in the sun-thaw; whether the eave-drops fall

Heard only in the trances of the blast,

Or if the secret ministry of frost

Shall hang them up in silent icicles,

Quietly shining to the quiet Moon.

15. Zakia

Alexander Pushkin – 3 short poems

Echo

If beasts within a silent forest moan,

if trumpets sound, if thunder rolls and cracks,

Or young girls sing almost inaudibly

For each initial tone

The atmosphere resounds quite suddenly

With a response, your own.

You listen to the peal of distant thunder,

The rumbling voice of violent waves and storm,

And hear the village shepherd's lonely cry —

And then you send your answer,

But hear no echo, there is no reply...

This also, poet, is your nature.

(Translated by Michael Mesic)

Awakening

O dreams, O dreams,

Where are your delights?

Oh, where are you,

The joys of night?

The joyous dream

Is vanished,

And in a deep darkness

I woke up

Alone.

The deathly-still night

Surrounds my bed.

The dreams of love

Grew cold in a moment,

And flew away

As a flock of birds.

But my soul

Is still full of desires,

And catches

The memories of a dream.

O love, O love,

Listen to my prayers,

Send me again

Your sweet visions,

And in the morning

Let me die

In ecstasy

With no awakening

(Translated by Dmitri Smirnov )

I loved you

I loved you, and I probably still do,

And for a while the feeling may remain... But let my love no

longer trouble you,

I do not wish to cause you any pain.

I loved you; and the hopelessness I knew, The jealousy, the

shyness - though in vain - Made up a love so tender and so true

As may God grant you to be loved again.

(Translated by Genia Gurarie)

I look forward to our August Session when we Celebrate the English Romantic Poets. Thanks to the Corona Pandemic, we met this year on Zoom. Missed being with the other readers in person. But it was a beautiful Session. Celebrating all those wonderful Poets. Joe, you put in a lot of efforts to recreate and expand that memorable event in your blog.

ReplyDelete