My Brilliant Friend – first edition of the English translation, 2012, by Europa Editions

“Elena Ferrante may be the best contemporary novelist you have never heard of,” said The Economist in a review one year after Europa Editions brought out the English translation of L‘amica geniale as My Brilliant Friend. In the years following 2012 three other novels were published that follow the two friends as they grow up – The Story of a New Name (2013), Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay (2014), and The Story of the Lost Child (2015). The four novels constitute the Neapolitan Novels quartet by Elena Ferrante. The first two books in the series have been adapted into an HBO television series entitled My Brilliant Friend.

The HBO Series starring Gaia Girace as Lila and Margarita Mazzuco as Lenù

Elena Ferrante, the author, has maintained a studied anonymity, although she is willing to answer questions by e-mail, via her publisher. Her translator into English, Ann Goldstein, an editor at The New Yorker, did not have access to her directly; the film directors who transferred her novels to the screen had only the most fleeting help from her. Her attitude is summed up in a comment she made: “I believe that books, once they are written, have no need of their authors.”

A collection of essays, letters and interviews by Elena Ferrante

For Ferrante’s heroines, life is a conundrum of attachment and detachment. Illustration by Annette Marnat in The New Yorker

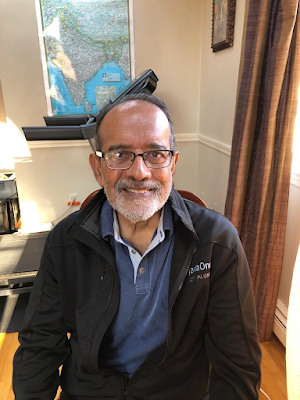

Ann Goldstein – The self-effacing translator of Italian author Elena Ferrante is an editor at The New Yorker

About Elena Ferrante and the Novel My Brilliant Friend

Since there is no official photograph of the author, it is Ann Goldstein, the translator, who must stand in – as she does at literary gatherings and panel discussions about Elena Ferrante. But Goldstein has never met the author.

Elena Ferrante is the pseudonym used by the author of many novels, the most famous being this set of 4 novels titled the Neapolitan novels. The quartet of novels has been published in 48 countries and sold 16 million copies worldwide as of 2020. Ferrante says that books, once they are written, have no need of their authors. Anonymity is key to her writing.

1992 saw publication of her first novel L'amore molesto (1992; English translation: Troubling Love, 2006); it was filmed as Nasty Love (1995). A number of Ferrante’s letters and interviews have been collected and published as Frantumaglia. From them, we learn that she grew up in Naples, and has lived for periods outside Italy. She has a classics degree; she has referred to being a mother. Many have tried to guess at her identity by computer textual comparison with known authors. In 2016 some sleuthing work by an Italian investigative journalist concluded that Anita Raja, a Rome-based German-to-Italian translator, is the real author behind the Ferrante pseudonym. Others claim that a writer's truest self is the books they write and there is no need to search behind it for the flesh and blood author if she wishes to preserve her anonymity.

Several of her novels have been turned into films: Troubling Love (L'amore molesto) became the feature film Nasty Love, while The Days of Abandonment, and The Lost Daughter also were filmed. One director stated the screenplay was almost given in her novels and he only had to add the visuals. In 2016, it was reported that a 32-part television series, The Neapolitan Novels, was in the works. Joe and KumKum have seen 16 episodes of Seasons 1 and 2 of the series on HBO. A more complete list of Ferrante’s works is available in the wiki article.

The Neapolitan novels follow the friendship of two women, Lila and the narrator Lenù. The first novel, My Brilliant Friend, covers their childhood and adolescence, up to the age of 16. They live in a run-down neighbourhood of Naples, where money is scarce and expectations for the future are bleak – no more than staying in the neighbourhood and working in the family business, or if a girl is lucky, marrying into a well-to-do family. Both girls are intelligent and curious, with Lila devouring as many books as she can borrow across all of her family’s library cards and teaching herself Latin and Greek. Lila’s intellectual gifts are more prominent and push Lenù to do just as well at school, if not better, and both girls are encouraged to stay with scholastics beyond the standard age of 12. However, like so many things, whether they can or not comes down to money. Lenù’s family (begrudgingly) scrapes the funds together; Lila’s refuses.

Clearly, both the girls initially see education as a way out of poverty, and a step toward getting out their under-privileged surroundings. It is only Lenù who is able to pursue that path and attend university finally. Lila has to stay on and navigate the intricate societal maze of conflicting relationships in her deprived neighbourhood.

The story of the friendship between Elena Greco and Lila Cerullo, spanning six decades in Naples, is an acute portrayal of the conflicts inherent in many deep female friendships. Unsparingly, Ferrante looks at the violence and patriarchy of southern Italy after WWII. In My Brilliant Friend she has created strong female characters that shine in contrast with the mediocre, dull, and often violent males.

In an essay in the New York Times Elena Ferrante has lamented how women are still dominated by male power even in storytelling. She writes: “Our widespread complicity is in fact a serious problem. Power is still firmly in male hands, and if, in societies with solid democratic traditions, we are more frequently given access to positions of command, it is only on condition that we show that we have internalized the male method of confronting and resolving problems. As a result, we too often end up demonstrating that we are acquiescent, obedient and equal to male expectations.”

Alongside stunning commercial success, the Neapolitan novels have been praised by the critics as a work of genius, an outstanding feminist tetralogy. However, in the novel itself Ferrante says she’s not a great writer (if you grant that the author has transferred her persona to that of Lenù): “Lila was able to speak through writing; unlike me when I wrote […] she expressed herself in sentences that were well constructed, and without error, even though she had stopped going to school, but—further—she left no trace of effort, you weren’t aware of the artifice of the written word.”

Naples, the setting for Ferrante's novels (Vesuvius is in the background)

Naples, on the Eastern coast of Italy, 220 km south of Rome, is always in the background of the novel. It is part of the famed Amalfi coast, the city from which tourists embark for a short ride to see Pompeii in the shadow of Mount Vesuvius, still active as a volcano. For a photo essay on Elena Ferrante’s Naples click on this link. The story is set in the post-war era of the 1950s and 60s when Communist ideology was still a major political force, and people were emerging from modest working class backgrounds into a middle class. Education was the key driver of class mobility.

The setting of the novel is a rough neighbourhood, thought to be Ruine Luzzatti, behind the central station. Since Ferrante takes care to name the streets, a modern tourist could make a novelistic tour to survey where Lenù and Lila grew up and see the stradone (avenue) where many significant actions in the novel take place. Although a reference is often made to the Neapolitan dialect, we have it from the translator, Ann Goldstein, that the novel itself contains no dialogue in dialect, probably because it would not have been easily understood by the Italian readers for whom Elena Ferrante wrote.

Who is the ‘Brilliant Friend’ in the novel? Is it Lenù or Lila? You will concede it is really Lila, in spite of her labelling Lenù as the one who must “be the best of all, boys and girls.”

Granted that Lenù can put in the work, yet those flights of fancy and inspiration that gave rise to designs for Cerullo shoes – only Lila can attain. Recall Lenù’s remarking that Lila's genius in writing was that “she left no trace of effort, you weren’t aware of the artifice of the written word.” Such gifts are given, but they have to be cultivated. What the novel makes one aware is that genius can arise at random anywhere, and the first duty of parents and educators is to recognise and nourish that tender plant, no matter in what unconventional direction it takes the child. Though Lila could not transfer her gift, surely her adjuration to be the best motivated Lenù to become what Lila could not – an author; not the author of their childish fancy, who would make a lot of money and escape poverty by writing a book, but one who would use her writing as an act of memorial love for her lost friend.

Some questions occur to one's mind. Education in Italy has been free to the age of fourteen since the 1920s, and in later times up to high school. Hence, the difficulties the parents of Lenù and Lila face in permitting the bright girls to attend school is inexplicable; unless it be that the girls were kept back to work at home and help the family economically. A second mystery is that the role of religion as a definite influence in the lives of the people is hardly mentioned. Perhaps this is owing to a bias the author expressed frankly in one of her interviews, A Conversation with Elena Ferrante:

“... since the age of fifteen, I haven’t believed in the kingdom of any God, in Heaven or on Earth—in fact, wherever you place it, it seems dangerous to me.”

A third point is the absence of the famous Neapolitan songs in the entire novel – songs like 'O sole mio, Torna a Surriento, and many others, which have been sung by all the leading singers, such as Caruso, Pavarotti and Bocelli.

I cannot resist a reference to Dean Martin singing In Napoli. Yet another of his inimitable songs, That's Amore, has the unforgettable lines:

When you walk in a dream

But you know, you're not dreaming, signore

Scusami, but you see

Back in old Napoli, that's amore

But one song, not so famous, is mentioned in the novel, Lazarella.

The English Translation

Finally a word about the translation to English. It shows the lack of critical reading by another reliable editor – there are too many passages which give trouble to the reader, passages from which no clear sense can be made out. Yet other passages contain long unwieldy sentences that betray a slavish adherence to the Italian structure, and come off as clumsy in English. Two illustrations follow.

Ch 8.

“So that, when the teacher sent her into the field to give the moods or tenses of verbs or solve math problems, hearts grew bitter. Lila was too much for anyone.”

Yes, the Italian does say:

La maestro mandava in campo lei

But in English the meaning is not ‘sent her into the field’, which is meaningless since they are in a competition inside a classroom; a more correct translation would be ‘entered her in a contest’

Ch 39.

“This wealth of adolescence proceeded from a fantastic, still childish illumination—the designs for extraordinary shoes— but it was embodied in the petulant dissatisfaction of Rino, who wanted to spend like a big shot, in the television, in the meals, and in the ring with which Marcello wanted to buy a feeling, and, finally, from step to step, in that courteous youth Stefano, who sold groceries, had a red convertible, spent forty-five thousand lire like nothing, framed drawings, wished to do business in shoes as well as in cheese, invested in leather and a workforce, and seemed convinced that he could inaugurate a new era of peace and well-being for the neighborhood: it was, in short, wealth that existed in the facts of every day, and so was without splendor and without glory.”

This 133-word sentence is the translation of the following passage in Italian:

Questa ricchezza dell’adolescenza muoveva sì da un’illuminazione fantastica ancora infantile – i disegni di scarpe mai viste – ma s’era materializzata nell’insoddisfazione rissosa di Rino che voleva spendere da gran signore, nella televisione, nelle paste e nell’anello di Marcello che mirava a comprare un sentimento, e infine, di passaggio in passaggio, in quel giovane cortese, Stefano, che vendeva salumi, aveva un’auto rossa decappottabile, spendeva quaranta cinquemila lire come niente, incorniciava disegnini, voleva commerciare oltre che in provoloni anche in scarpe, investiva in pellame e forza lavoro, sembrava convinto di saper inaugurare una nuova epoca di pace e di benessere per il rione: era, insomma, ricchezza che stava nei fatti di ogni giorno, e perciò senza splendore e senza gloria.

The translation of the long Italian sentence into an equally long English sentence, structured in the same fashion, makes the text unwieldy and gives a great deal of trouble to the reader. Nobody writes like that in contemporary English.

First of all ‘illuminazione’ should be translated simply as a flash of inspiration, not illumination.

Secondly, ‘spendere … nella televisione’ should not be translated as ‘ spend … in the television’ but ‘spend … on television’ , etc.

By the time you come to the phrase ‘in that courteous youth Stefano,’ the reader has forgotten that what qualifies this phrase is ‘was embodied,’ which stood 38 words before.

Again, so many auxiliary clauses are added to qualify Stefano:

– who sold groceries,

– had a red convertible,

– spent forty-five thousand lire like nothing,

– framed drawings,

– wished to do business in shoes as well as in cheese,

– invested in leather and a workforce,

etc.

The reader runs out of breath.

And finally at the end of that litany, the reader is reminded it all started with the ‘wealth’ which was alluded to 114 words before.

Let’s try a more English translation and frame it in manageable sentences, preserving as much of Goldstein’s original as possible:

“This fecundity of adolescence arose from a fantastic inspiration of childhood –– the designs for those extraordinary shoes. But it manifested itself in the petulant dissatisfaction of Rino who wanted to spend like a big shot: on a television, on eating out, and on a ring of the kind with which Marcello sought to buy affections. And then Rino thought of Stefano, such a refined youth, who sold groceries, but owned a red convertible and thought nothing of spending forty-five thousand lire to buy shoe designs to start a business. This was a lad who could invest in a workforce in order to transform the neighbourhood with peaceful progress. Yet, so rich a vision was without splendour or glory, for it was all anchored in the facts of everyday life.”

Zakia

Zakia went first in reading as she needed to leave early. She admired the forthright speech of Lila in this passage from Chapter 24. Marcello Solara has stopped the car seeing Lila, to tell her he dreamt that she said ‘Yes’ when he asked her to become his fiancée.

Lila does not hide her feelings in diplomatic words. She is fearless in rebutting Marcello when he tries to woo her. What Zakia found appealing was that she did not mince her words. Joe said it is quite characteristic of Lila that she confronts adults with courage – in this case, Marcello, who may be 4 or 5 years older. She gives a damn for the consequences when she gets things off her mind, and as a result suffers many insults and injuries. Joe remembered a shocking scene in the film when she is thrown out of the window – by her own father. My goodness! She fell on the road Dhadap! and broke her hand. That's the mettle of which she's made, Joe said. She must have been made out of some metal, Zakia replied.

Arundhaty has already read about a thousand pages of the Neapolitan novel quartet, but chose this early passage in Chapter 10 about the lost dolls and the girls entering the spooky cellar to find them, because this is where the relationship is first established between the two girls. Though Lila and Lenù were close, this passage shows Lila could be mean. That streak in her character surfaced from time to time. Although they were good friends there were times when Lenù wanted to avoid Lila.

KumKum found this passage fascinating. Lila always wanted Lenù to be educated, even though she could not follow in her footsteps on an academic path. But Lenù knew she could never match Lila's native genius, and might fall short if she tried to acquire her courage. The passage reveals how Lenù deals with Lila; she says, “What you do, I do.” Priya said it seems as if Lenù always sought Lila's approval, yet tries to maintain her own ground. This conflict is there throughout the novel.

Priya noted that at the beginning of the novel you feel Lenù is the ultimate victor as she is the one who gets to write the account of their life over sixty years . In the introduction before the novel begins Lenù writes:

“We’ll see who wins this time, I said to myself. I turned on the computer and began to write—all the details of our story, everything that still remained in my memory.”

Arundhaty has only 300 pages to finish of the quartet, but she is not yet sure of the outcome. Priya asked Arundhaty whether Lila returns at the end. Arundhaty has no idea. KumKum has also followed the novels and has 200 pages left. Joe said each reader should have the chance to discover how the fourth novel, The Story of the Lost Child, ends. From whatever Joe has read about Ferrante, she is not one for happy endings. It may not be the neat wrapping up of a yarn as was expected formerly; Ferrante is a new kind of author. She is truer to life than most authors who would write something that has a nice closure to it. As far as she is concerned life has no closure. Arundhaty hazarded that finally Elena Ferrante may find a way to put her namesake Lenù down – that's her guess.

Priya said that Lenù says at the beginning: “since I know her well, or at least I think I know her, I take it for granted that she has found a way to disappear, to leave not so much as a hair anywhere in this world.”

Joe

The passage is from Chapter 13 where Elena refuses to join a car-ride with the Solara brothers, Marcello and Michele. This episode is very striking in the HBO TV series that transformed the story into film; two seasons of 8 episodes each are available for viewing. More episodes are under filming and a third season will be out soon. Arundhaty thought even before knowing about the HBO series that a perfect take on the novels would be as a TV series.

It is in little details that the author conveys graphically the scene to make it come alive through the narration, for instance: “the knife had already cut Marcello’s skin, a scratch from which came a tiny thread of blood.”

Pamela

Pamela read from Chapter 16 where Lenù and Lila play truant from school in order to satisfy their curiosity about the sea. Pamela liked this passage because it reminded her of a friend, Twinkle (?), who is now in Norway, married to a Danish man. She is a Norwegian citizen. She and Pamela were childhood friends from the age of 3 or 4. Until 16 they were together and then she was taken away by foster parents to Norway.

She was very bold, like Lila, and brilliant and capable. She would influence Pamela to do things that Pamela's parents would not allow, because they were strict. Boundaries of distance, time and company were imposed on Pamela but this girl would make Pamela break all those rules. Everyone laughed when Pamela said she used to enjoy this rebellion. Surprisingly when they returned from an outing Pamela's father would scold her friend severely, not Pamela. The friend would look repentant and demure, but after she was dismissed, she would call and say: “Pammy, you enjoyed it, no? That's enough for me.”

She would do it all over again. Pamela's father was sure his daughter was not capable of revolting on her own; it was her friend's bad influence. Even now Pamela recalls all those times they broke rules and laughs with her friend.

Pamela said in Delhi she has had the same experience of Lila and Lenù, when a man exposed himself to them: “We also saw a fat man in an undershirt who emerged from a tumbledown house, opened his pants, and showed us his penis.”

But Pamela and her friend were very smart. They turned round and told the man: “Bahut chhota hai.” (It's tiny). The fellow packed up and ran. Laughter all round among the readers! Joe said: “Pamela you would have humiliated Trump!”

Joe said there's another character trait of Lila in this passage which appears at this young age. That is, she will put up a bold front, as though she is in command of things, when she knows inside that she is stepping out into the great unknown and she doesn‘t know everything. It is the ability to display that confidence, whatever quaking fears you have inside, that inspires people and later in life and makes them willing to follow you.

Priya

Priya chose the part from Chapter 38 where the proposed shoes to be made by Lila's father and brother are to be branded as ‘Cerullo,’ after the family's surname. The shoes are symbolic of hope and hard work. Also Italian shoes are so famous that everyone would dream of owning a pair of hand-made Italian shoes, Priya said. From the praise it received Priya imagines the design made by Lila would have been fabulous. Marcello Solara (of the bar-pastry shop) and Stefano Carracci (the grocer) are both vying for Lila's hand but she has decided on Stefano. He pays money to buy the shoes, and extra to buy the drawings Lila made for future designs. Marcello has little idea of the art and craft of shoe-making, Priya said, and none at all for the design sensibility of Lila.

Now we can all dream of having Italian shoes. Joe remembered the case of the O.J. Simpson murder trial where this football (American football) player was arrested and charged with the murders of his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend, Ron Goldman. The print of a Bruno Magli size 12 Lorenzo boot (same as Simpson was once seen wearing) was found near the murder scene. But the shoe was not recovered and on a technical matter (improper handling of evidence) Mr Simpson was found not guilty.

Priya recalled a Chinese shoe-maker who had a shop on Princess Street in Fort Kochi – she was harking back to1989 when she first came here. Both Pamela and Priya have had shoes made by him from photographs of shoes in fashion magazines. These shoes excited comment when worn in Bombay. Pamela misses the shoe-maker and was happy Priya remembered him, but not being a journalist at the time she did not have the chance to do a story about him, take photographs and so on.

In Calcutta the Chinese shoe-makers congregated in a row of shops on Bentinck Street near Esplanade. Their tanneries were located in Tangra on the Eastern side of the city in marshy land. Today that thriving business is all gone.

Shoba

In the next Chapter, 39, Stefano proposes to Lila at this shop which is being refitted to make new shoes, rather than to repair shoes.

At the end of the novel at the wedding party Marcello Solara is discovered to be wearing this same pair of shoes and Lila is at a loss to know how he got them. His family, the Solaras, are alleged from the very beginning of the novel to have been a goonda kind of clan who imposed their will on the neighbourhood through thuggery. KumKum said Lila and Lenù got some money out of the father, Don Achille (he is given a title like a mafia don's).

Saras

Saras shut down her video for lack of bandwidth and read only with audio; but we could all visualise her double bindi from the reader photo she sent in advance. The passage was long and starts with the arguments with Stefano's mother and his sister when Lila is preparing her trousseau. Lenù is breaking away from the shadow of Lila and coming into her own.

In this passage from Chapter 53 Lenù in class called the Christian religion “the same thing as collecting trading cards while the city burns in the fires of hell.” Her tirade against religion offends the religion teacher who sends her out of the class. Later, with the intervention of another rationalist teacher she is allowed back in and apologises for her aggressive tone, though not for the content of her remarks. Joe noted that in this scene also Lenù says she drew her courage from Lila: “I continued to assign her an authority that made me bold enough to challenge the religion teacher.”

It's a deep and complicated relationship between the two girls. It's a friendship but a friendship that is fraught between two people who compete with each other, who draw strength from each other, and consult each other in important life decisions. Joe liked that feature of the book, that throughout it is about a friendship. It's not the usual kind of friendship that is linear and straightforward. It is a friendship that has many twists and turns. The author as a novelist exploits every one of the incidents in the novel to make the characters appear much more complicated than the people we encounter in real life. Although, we do encounter cruel people, we do encounter cynical people, and we do encounter people who are like some of these goondas in this book. But the friendship rises above it all.

Joe didn't quite understand what the author meant by ‘trading cards.’ Two readers said it is baseball cards she is referring to, which children in America collect with pictures of champion baseball players. There is probably some Italian equivalent, Saras thought.

Saras agreed on another matter with Joe, that the sentences are convoluted, and sometimes they go on and on and on, and you lose track of what exactly the author is trying to convey at times. There is excruciating detail in some places. Some of the details are telling and make the scene come alive in your mind, like the thin thread of blood down Marcello Solara's throat when Lila holds a knife to him.

Saras remarked it is quite evident this is a translation. Joe agrees, it does come out like that. The English sounds non-native. KumKum said the language does not align with normal English construction in many places.

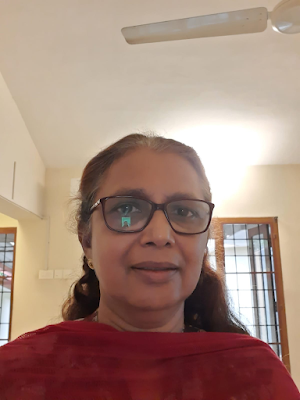

KumKum

KumKum read passage near the end. All along she thought the brilliant friend was Lila. Here Lila is calling Lenù her brilliant friend. Maybe so, ultimately she is the one who perseveres in her studies.

Priya thought it was a nice reading about a significant passage through life, one of them is entering the state of matrimony, knowing it is going to be a constriction, and wishes to liberate the other who should continue to embrace the womanly power residing in her superior mind.

Shoba said it is one of the best passages in the book; it is also the passage where the title of book occurs. Joe said the sentence, “you have to be the best of all, boys and girls”, is almost a wistful statement, signifying a sadness on her part that she, Lila, is abandoning her genius and whatever talent she had, in favour of a commonplace and plebeian choice for girls in that poverty-stricken neighbourhood, namely to marry up and get out of poverty that way. In this statement she is not only congratulating her friend Lenù, but there is a little regret for herself.

KumKum didn't see regret but rather Lila is shown accepting her fate, as she did from the beginning. By not pursuing school as Lenù did she was accepting the consequences. It is touching that what she cannot do in future, she wants her friend to accomplish. Joe agreed it is touching.

Lila is wise enough to know she is not following the best course, as she will find out very soon, said KumKum. Everyone wants to know the ending of the fourth novel which Arundhaty and KumKum are closest to attainiing. Priya is curious to know. Arundhaty got the quartet of novels in their Kindle version as a prize for the best costume at the session of Humorous Poems in Dec 2020.

The Readings

Arundhaty

Ch 10 – Lila and Elena go searching for their lost dolls in the cellars

We saw each other in the courtyard more and more frequently. We showed off our dolls to each other but without appearing to, one in the other’s vicinity, as if each of us were alone. At some point we let the dolls meet, as a test, to see if they got along. And so came the day when we sat next to the cellar window with the curled grating and exchanged our dolls, she holding mine and I hers, and Lila abruptly pushed Tina through the opening in the grating and dropped her.

I felt an unbearable sorrow. I was attached to my plastic doll; it was the most precious possession I had. I knew that Lila was mean, but I had never expected her to do something so spiteful to me. For me the doll was alive, to know that she was on the floor of the cellar, amid the thousand beasts that lived there, threw me into despair. But that day I learned a skill at which I later excelled. I held back my despair, I held it back on the edge of my wet eyes, so that Lila said to me in dialect:

“You don’t care about her?”

I didn’t answer. I felt a violent pain, but I sensed that the pain of quarreling with her would be even stronger. I was as if strangled by two agonies, one already happening, the loss of the doll, and one possible, the loss of Lila. I said nothing, I only acted, without spite, as if it were natural, even if it wasn’t natural and I knew I was taking a great risk. I merely threw into the cellar her Nu, the doll she had just given me.

Lila looked at me in disbelief.

“What you do, I do,” I recited immediately, aloud, very frightened.

“Now go and get it for me.”

“If you go and get mine.”

We went together. At the entrance to the building, on the left, was the door that led to the cellars, we knew it well. Because it was broken—one of the panels was hanging on just one hinge—the entrance was blocked by a chain that crudely held the two panels together. Every child was tempted and at the same time terrified by the possibility of forcing the door that little bit that would make it possible to go through to the other side. We did it. We made a space wide enough for our slender, supple bodies to slip through into the cellar.

Once inside, we descended, Lila in the lead, five stone steps into a damp space, dimly lit by the narrow openings at street level. I was afraid, and tried to stay close behind Lila, but she seemed angry, and intent on finding her doll. I groped my way forward. I felt under the soles of my sandals objects that squeaked, glass, gravel, insects. All around were things not identifiable, dark masses, sharp or square or rounded. The faint light that pierced the darkness sometimes fell on something recognizable: the skeleton of a chair, the pole of a lamp, fruit boxes, the bottoms and sides of wardrobes, iron hinges. I got scared by what seemed to me a soft face, with large glass eyes, that lengthened into a chin shaped like a box. I saw it hanging, with its desolate expression, on a rickety wooden stand, and I cried out to Lila, pointing to it. She turned and slowly approached it, with her back to me, carefully extended one hand, and detached it from the stand. Then she turned around. She had put the face with the glass eyes over hers and now her face was enormous, with round, empty eye sockets and no mouth, only that protruding black chin swinging over her chest.

Joe

Ch 13 – Elena declines a car-ride with the Solara brothers, Marcello and Michele

Instead of going straight ahead as if neither he nor the car nor his brother existed; instead of continuing to talk to Lila and ignoring them, I turned and, out of a need to feel attractive and lucky and on the verge of going to the rich people’s school, where I would likely find boys with cars much nicer than the Solaras’, said, in Italian:

“Thank you, but we can’t.”

Marcello reached out a hand. I saw that it was broad and short, although he was a tall, well-made young man. The five fingers passed through the window and grabbed me by the wrist, while his voice said: “Michè, slow down, you see that nice bracelet the porter’s daughter is wearing?”

The car stopped. Marcello’s fingers around my wrist made my skin turn cold, and I pulled my arm away in disgust. The bracelet broke, falling between the sidewalk and the car.

“Oh, my God, look what you’ve made me do,” I exclaimed, thinking of my mother.

“Calm down,” he said, and, opening the door, got out of the car. “I’ll fix it for you.”

He was smiling, friendly, he tried again to take my wrist as if to establish a familiarity that would soothe me. It was an instant. Lila, half the size of him, pushed him against the car and whipped the shoemaker’s knife under his throat.

She said calmly, in dialect, “Touch her again and I’ll show you what happens.”

Marcello, incredulous, froze. Michele immediately got out of the car and said in a reassuring tone: “Don’t worry, Marcè, this whore doesn’t have the guts.”

“Come here,” Lila said, “come here, and you’ll find out if I have the guts.”

Michele came around the car, and I began to cry. From where I was I could see that the point of the knife had already cut Marcello’s skin, a scratch from which came a tiny thread of blood. The scene is clear in my mind: it was still very hot, there were few passersby, Lila was on Marcello as if she had seen a nasty insect on his face and wanted to chase it away. In my mind there remains the absolute certainty I had then: she wouldn’t have hesitated to cut his throat. Michele also realized it.

“O.K., good for you,” he said, and with the same composure, as if he were amused, he got back in the car. “Get in, Marcè, apologize to the ladies and let’s go.”

Lila slowly removed the point of the blade from Marcello’s throat. He gave her a timid smile, his gaze was disoriented.

“Just a minute,” he said.

He knelt on the sidewalk, in front of me, as if he wanted to apologize by subjecting himself to the highest form of humiliation. He felt around under the car, recovered the bracelet, examined it, and repaired it by squeezing with his nails the silver link that had come apart. He gave it to me, looking not at me but at Lila. It was to her that he said, “Sorry.” Then he got in the car and they drove off.

“I was crying because of the bracelet, not because I was scared,” I said.

Pamela

Ch 16 – Elena and Lila play truant from school in order to satisfy their curiosity about the sea.

It was early morning and already hot. There was a strong odor of earth and grass drying in the sun. We climbed among tall shrubs, on indistinct paths that led toward the tracks. When we reached an electrical pylon we took off our smocks and put them in the schoolbags, which we hid in the bushes. Then we raced through the scrubland, which we knew well, and flew excitedly down the slope that led to the tunnel. The entrance on the right was very dark: we had never been inside that obscurity. We held each other by the hand and entered. It was a long passage, and the luminous circle of the exit seemed far away. Once we got accustomed to the shadowy light, we saw lines of silvery water that slid along the walls, large puddles. Apprehensively, dazed by the echo of our steps, we kept going. Then Lila let out a shout and laughed at the violent explosion of sound. Immediately I shouted and laughed in turn. From that moment all we did was shout, together and separately: laughter and cries, cries and laughter, for the pleasure of hearing them amplified. The tension diminished, the journey began.

Ahead of us were many hours when no one in our families would look for us. When I think of the pleasure of being free, I think of the start of that day, of coming out of the tunnel and finding ourselves on a road that went straight as far as the eye could see, the road that, according to what Rino had told Lila, if you got to the end arrived at the sea. I felt joyfully open to the unknown. It was entirely different from going down into the cellar or up to Don Achille’s house. There was a hazy sun, a strong smell of burning. We walked for a long time between crumbling walls invaded by weeds, low structures from which came voices in dialect, sometimes a clamor. We saw a horse make its way slowly down an embankment and cross the street, whinnying. We saw a young woman looking out from a balcony, combing her hair with a flea comb. We saw a lot of small snotty children who stopped playing and looked at us threateningly. We also saw a fat man in an undershirt who emerged from a tumbledown house, opened his pants, and showed us his penis. But we weren’t scared of anything: Don Nicola, Enzo’s father, sometimes let us pat his horse, the children were threatening in our courtyard, too, and there was old Don Mim who showed us his disgusting thing when we were coming home from school. For at least three hours, the road we were walking on did not seem different from the segment that we looked out on every day. And I felt no responsibility for the right road. We held each other by the hand, we walked side by side, but for me, as usual, it was as if Lila were ten steps ahead and knew precisely what to do, where to go. I was used to feeling second in everything, and so I was sure that to her, who had always been first, everything was clear: the pace, the calculation of the time available for going and coming back, the route that would take us to the sea. I felt as if she had everything in her head ordered in such a way that the world around us would never be able to create disorder. I abandoned myself happily. I remember a soft light that seemed to come not from the sky but from the depths of the earth, even though, on the surface, it was poor, and ugly.

Then we began to get tired, to get thirsty and hungry. We hadn’t thought of that. Lila slowed down, I slowed down, too. Two or three times I caught her looking at me, as if she had done something mean to me and was sorry. What was happening? I realized that she kept turning around and I started turning around, too. Her hand began to sweat. The tunnel, which was the boundary of the neighborhood, had been out of sight for a long time. By now the road we had just traveled was unfamiliar to us, like the one that stretched ahead. People appeared completely indifferent to our fate. Around us was a landscape of ruin: dented tanks, burned wood, wrecks of cars, cartwheels with broken spokes, damaged furniture, rusting scrap iron. Why was Lila looking back? Why had she stopped talking? What was wrong?

Zakia

Ch 24 – Marcello Solara stops the car seeing Lila, to tell her he dreamt that she said ‘Yes’ when he asked her to become his fiancée.

Marcello was driving the 1100, by himself, without his brother, and had seen her as she was going home along the stradone. He hadn’t driven up alongside her, he hadn’t called to her from the window. He had left the car in the middle of the street, with the door open, and approached her.

Lila had kept walking, and he followed. He had pleaded with her to forgive him for his behavior in the past, he admitted she would have been absolutely right to kill him with the shoemaker’s knife. He had reminded her, with emotion, how they had danced rock and roll so well together at Gigliola’s mother’s party, a sign of how well matched they might be. Finally he had started to pay her compliments: “How you’ve grown up, what lovely eyes you have, how beautiful you are.” And then he told her a dream he had had that night: he asked her to become engaged, she said yes, he gave her an engagement ring like his grandmother’s, which had three diamonds in the band of the setting. At last Lila, continuing to walk, had spoken. She had asked, “In that dream I said yes?” Marcello confirmed it and she replied, “Then it really was a dream, because you’re an animal, you and your family, your grandfather, your brother, and I would never be engaged to you even if you tell me you’ll kill me.”

“You told him that?”

“I said more.”

“What?”

When Marcello, insulted, had replied that his feelings were delicate, that he thought of her only with love, night and day, that therefore he wasn’t an animal but one who loved her, she had responded that if a person behaved as he had behaved with Ada, if that same person on New Year’s Eve started shooting people with a gun, to call him an animal was to insult animals. Marcello had finally understood that she wasn’t joking, that she really considered him less than a frog, a salamander, and he was suddenly depressed. He had murmured weakly, “It was my brother who was shooting.” But even as he spoke he had realized that that excuse would only increase her contempt. Very true. Lila had started walking faster and when he tried to follow had yelled, “Go away,” and started running. Marcello then had stopped as if he didn’t remember where he was and what he was supposed to be doing, and so he had gone back to the 1100.

Priya

Ch 38 – A new brand of shoes called Cerullo is born

“He’s proposing to transform the shoe shop into a workshop for making Cerullo shoes.”

“And the money?” Rino asked cautiously.

“He’ll invest it.”

“He told you?” Fernando, incredulous, was alarmed, immediately followed by Nunzia.

“He told the two of you,” Lila said, indicating her father and brother.

“But he knows that handmade shoes are expensive?” “You showed him.”

“And if they don’t sell?”

“You’ve wasted the work and he’s wasted the money.” “And that’s it?”

“That’s it.”

The entire family was upset for days. Marcello moved to the background. He arrived at night at eight-thirty and dinner wasn’t ready. Often he found himself alone in front of the television with Melina and Ada, while the Cerullos talked in another room.

Naturally the most enthusiastic was Rino, who regained energy, color, good humor, and, as he had been the close friend of the Solaras, so he began to be Stefano’s close friend, Alfonso’s, Pinuccia’s, even Signora Maria’s. When, finally, Fernando’s last reservation dissolved, Stefano went to the shop and, after a small discussion, came to a verbal agreement on the basis of which he would put up the expenses and the two Cerullos would start production of the model that Lila and Rino had already made and all the other models, it being understood that they would split the possible profits half and half. He took the documents out of a pocket and showed them to them one after another.

“You’ll do this, this, this,” he said, “but let’s hope that it won’t take two years, as I know happened with the other.”

“My daughter is a girl,” Fernando explained, embarrassed, “and Rino hasn’t yet learned the job well.”

Stefano shook his head in a friendly way.

“Leave Lina out of it. You’ll have to take on some workers.”

“And who will pay them?” Fernando asked.

“Me again. You choose two or three, freely, according to your judgment.”

Bruno Magli shoes

Fernando, at the idea of having, no less, employees, turned red and his tongue was loosened, to the evident annoyance of his son. He spoke of how he had learned the trade from his late father. He told of how hard the work was on the machines, in Casoria. He said that his mistake had been to marry Nunzia, who had weak hands and no wish to work, but if he had married Ines, a flame of his youth who had been a great worker, he would in time have had a business all his own, better than Campanile, with a line to display perhaps at the regional trade show. He told us, finally, that he had in his head beautiful shoes, perfect, that if Stefano weren’t set on those silly things of Lina’s, they could start production now and you know how many they would sell. Stefano listened patiently, but repeated that he, for now, was interested only in having Lila’s exact designs made. Rino then took his sister’s sheets of paper, examined them carefully, and asked him in a lightly teasing tone:

“When you get them framed where will you hang them?”

“In here.”

Rino looked at his father, but he had turned sullen again and said nothing. “My sister agrees about everything?” he asked.

Stefano smiled: “Who can do anything if your sister doesn’t agree?”

He got up, shook Fernando’s hand vigorously, and headed toward the door. Rino went with him and, with sudden concern, called to him from the doorway, as Stefano was going to the red convertible:

“The brand of the shoes is Cerullo.”

Stefano waved to him, without turning: “A Cerullo invented them and Cerullo they will be called.”

Shoba

Ch 39 – Lina gets engaged to Marcello Solara

“He was a child,” she answered, with emotion, sweet as I had never heard her before, so that only at that moment did I realize that she was much farther along than what she had said to me in words.

In the following days everything became clearer. I saw how she talked to Stefano and how he seemed shaped by her voice. I adapted to the pact they were making, I didn’t want to be cut out. And we plotted for hours—the two of us, the three of us—to act in a way that would quickly silence people,

feelings, the arrangement of things. A worker arrived in the space next to the shoe shop and took down the dividing wall. The shoemaker’s shop was reorganized. Three nearly silent apprentices appeared, country boys, from Melito. In one corner they continued to do resoling, in the rest of the space Fernando arranged benches, shelves, his tools, his wooden forms according to the various sizes, and began, with sudden energy, unsuspected in a man so thin, consumed by a bitter discontent, to talk about a course of action.

Just that day, when the new work was about to begin, Stefano showed up. He carried a package done up in brown paper. They all jumped to their feet, even Fernando, as if he had come for an inspection. He opened the package, and inside were a number of small pictures, all the same size, in narrow brown frames. They were Lila’s notebook pages, under glass, like precious relics. He asked permission from Fernando to hang them on the walls, Fernando grumbled something, and Stefano had Rino and the apprentices help him put in the nails. When the pictures were hung, Stefano asked the three helpers to go get a coffee and handed them some lire. As soon as he was alone with the shoemaker and his son, he announced quietly that he wanted to marry Lila.

An unbearable silence fell. Rino confined himself to a knowing little smile and Fernando said finally, weakly, “Stefano, Lina is engaged to Marcello Solara.”

“Your daughter doesn’t know it.”

“What do you mean?”

Rino interrupted, cheerfully: “He’s telling the truth: you and Mamma let that shit come to our house, but Lina never wanted him and doesn’t want him.”

Fernando gave his son a stern look. The grocer said gently, looking around: “We’ve started out on a job now, let’s not get worked up. I ask of you a single thing, Don Fernà: let your daughter decide. If she wants Marcello Solara, I will resign myself. I love her so much that if she’s happy with someone else I will withdraw and between us everything will remain as it is now. But if she wants me—if she wants me—there’s no help for it, you must give her to me.”

“You’re threatening me,” Fernando said, but halfheartedly, in a tone of resigned observation.

“No, I’m asking you to do what’s best for your daughter.”

“I know what’s best for her.”

“Yes, but she knows better than you.”

And here Stefano got up, opened the door, called me, I was waiting outside with Lila.

“Lenù.”

We went in. How we liked feeling that we were at the center of those events, the two of us together, directing them toward their outcome. I remember the extreme tension of that moment. Stefano said to Lila, “I’m saying to you in front of your father: I love you, more than my life. Will you marry me?”

Lila answered seriously, “Yes.”

Fernando gasped slightly, then murmured, with the same subservience that in times gone by he had manifested toward Don Achille: “We’re offending not only Marcello but all the Solaras. Who’s going to tell that poor boy?”

Lila said, “I will.”

Saras

Ch 53 – Elena has to apologise for a tirade against religion

Then one morning I got into serious trouble. Since the religion teacher was constantly delivering tirades against the Communists, against their atheism, I felt impelled to react, I don’t really know if by my affection for Pasquale, who had always said he was a Communist, or simply because I felt that all the bad things the priest said about Communists concerned me directly as the pet of the most prominent Communist, Professor Galiani. The fact remains that I, who had successfully completed a theological correspondence course, raised my hand and said that the human condition was so obviously exposed to the blind fury of chance that to trust in a God, a Jesus, the Holy Spirit—this last a completely superfluous entity, it was there only to make up a trinity, notoriously nobler than the mere binomial father-son—was the same thing as collecting trading cards while the city burns in the fires of hell. Alfonso had immediately realized that I was overdoing it and timidly tugged on my smock, but I paid no attention and went all the way, to that concluding comparison. For the first time I was sent out of the classroom and had a demerit on my class record.

Once I was in the hall, I was disoriented at first—what had happened, why had I behaved so recklessly, where had I gotten the absolute conviction that the things I was saying were right and should be said?—and then I remembered that I had had those conversations with Lila, and saw that I had landed myself in trouble because, in spite of everything, I continued to assign her an authority that made me bold enough to challenge the religion teacher. Lila no longer opened a book, no longer went to school, was about to become the wife of a grocer, would probably end up at the cash register in place of Stefano’s mother, and I? I had drawn from her the energy to invent an image that defined religion as the collecting of trading cards while the city burns in the fires of hell? Was it not true, then, that school was my personal wealth, now far from her influence? I wept silently outside the classroom door.

But things changed unexpectedly. Nino Sarratore appeared at the end of the hall. After the new encounter with his father, I had all the more reason to behave as if he didn’t exist, but seeing him in that situation revived me, I quickly dried my tears. He must have realized that something was wrong, and he came toward me. He was more grown-up: he had a prominent Adam’s apple, features hollowed out by a bluish beard, a firmer gaze. It was impossible to avoid him. I couldn’t go back into the class, I couldn’t go to the bathroom, either of which would have made my situation more complicated if the religion teacher looked out. So when he joined me and asked why I was outside, what had happened, I told him. He frowned and said, “I’ll be right back.” He disappeared and reappeared a few minutes later with Professor Galiani.

Galiani was full of praise. “But now,” she said, as if she were giving me and Nino a lesson, “after the full attack, it’s time to mediate.” She knocked on the door of the classroom, closed it behind her, and five minutes later looked out happily. I could go back provided I apologized to the professor for the aggressive tone I had used. I apologized, wavering between anxiety about probable reprisals and pride in the support I had received from Nino and from Professor Galiani.

KumKum

Ch 57 – Lila, about to wed, tells Elena: ”you’re my brilliant friend, you have to be the best of all, boys and girls.”

March 12th arrived, a mild day that was almost like spring. Lila wanted me to come early to her old house, so that I could help her wash, do her hair, dress. She sent her mother away, we were alone. She sat on the edge of the bed in underpants and bra. Next to her was the wedding dress, which looked like the body of a dead woman; in front of us, on the hexagonal-tiled floor, was the copper tub full of boiling water. She asked me abruptly: “Do you think I’m making a mistake?”

“How?”

“By getting married.”

“Are you still thinking about the speech master?”

“No, I’m thinking of the teacher. Why didn’t she want me to come in?”

“Because she’s a mean old lady.”

She was silent for a while, staring at the water that sparkled in the tub, then she said, “Whatever happens, you’ll go on studying.”

“Two more years: then I’ll get my diploma and I’m done.”

“No, don’t ever stop: I’ll give you the money, you should keep studying.”

I gave a nervous laugh, then said, “Thanks, but at a certain point school is over.”

“Not for you: you’re my brilliant friend, you have to be the best of all, boys and girls.”

She got up, took off her underpants and bra, said, “Come on, help me, otherwise I’ll be late.”

I had never seen her naked, I was embarrassed. Today I can say that it was the embarrassment of gazing with pleasure at her body, of being the not impartial witness of her sixteen-year-old’s beauty a few hours before Stefano touched her, penetrated her, disfigured her, perhaps, by making her pregnant.

Thank you Joe, for this wonderful summary of our November session. As usual you have given us so much more than we could cover in our limited time . Your translation of the passage from the Italian makes it so much more readable than Ann Goldstein s!

ReplyDeleteMy Brilliant Friend Joe Cleetus who has consistently recorded documented photographed our readings and enhanced them in the blog. Congratulations on your exceptional efforts.

ReplyDeleteDear Joe, What a magnificent job you did in this blog! Not 200 pages, I still have to read 700 more pages.....initially overlooked the 4th book of the set. But the book has a strong pulling power, I know I will not rest until I finish the book. Then, I will read your blog again...

ReplyDelete