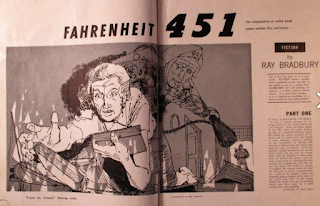

First Edition of ‘Fahrenheit 451’ signed by Ray Bradbury, published by Ballantine Books in 1953

The protagonist, Guy Montag, is a fireman who becomes

disillusioned with his job, and the society he lives in, after a series of

encounters with a mysterious young girl named Clarisse, and a retired professor

named Faber. Montag begins to secretly read books and becomes more and more

aware of the oppressive nature of his society. He eventually joins a group of

rebels who are working to preserve books and the knowledge they contain. The

novel explores themes of censorship, the dangers of conformism, and the power

of literature. Bradbury wrote the novel as a reaction to the McCarthyite

political climate of the 1950s and as a warning about the dangers of censorship

and the suppression of dissenting ideas.

https://www.britannica.com/event/Charlie-Hebdo-shooting

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/apr/07/book-bans-pen-america-school-districts

Even today in

India authorities attempt to use the police to squelch the expression of works

critical of the government. This is contrary to the latitude given in the

Constitution to a free press and to voice opinions that dissent from the

majority (peacefully, of course). Many writers face the fate of Perumal Murugan

who was hounded by Hindutva and caste-based groups which demanded a ban on his

book Madhorubhagan, saying it was derogatory in its depiction of

women and rituals. See:

Most recently a BBC documentary was not banned, but its exhibition was suppressed in many locations, including educational institutions, by using the police to interfere.

It is well to remember what Salman Rushdie, himself the object of severe threats from Iranian mullahs, said: “What is freedom of expression? Without the freedom to offend, it ceases to exist.”

The Indian writer Arundhati Roy has emphasised that freedom of expression is a fundamental human right and is essential for the functioning of a free and open society. She has also stressed the importance of protecting the rights of writers, journalists, and other artists to express their ideas freely, and the need to create an environment where dissenting voices can be heard.

Ray Bradbury was born in Illinois, but the family moved to Los Angeles in 1934 when he was 14 and he attended high school there. Even at a young age he knew that he would go into one of the arts. He was active in the drama club and would listen to radio plays and after the play was over, he would write the entire script from memory. The family lived in Hollywood and young Bradbury would roller-skate all over the neighbourhood hoping to meet celebrities.

In 1936, at a second-hand bookstore in Hollywood, Bradbury discovered a handbill promoting meetings of the Los Angeles Science Fiction Society. Excited to find that others shared his interest, Bradbury joined a weekly Thursday-night conclave at age 16.

Bradbury's lifelong passion for books began at an early age.His family could not afford to send him to college, so Bradbury began spending time at the Los Angeles Public Library where he educated himself. As a frequent visitor to his local libraries in the 1920s and 1930s, he recalls being disappointed because they did not stock popular science fiction novels, like those of H. G. Wells, because, at the time, they were not deemed literary enough. Between this and learning about the destruction of the Library of Alexandria, a great impression was made on Bradbury about the vulnerability of books to censure and destruction. Later, as a teenager, Bradbury was horrified by the Nazi book burnings and later by Joseph Stalin's campaign of political repression, the “Great Purge”, in which writers and poets, among many others, were arrested and often executed.Bradbury's first published story was Hollerbochen's Dilemma, which appeared in the January 1938 number of Forrest J. Ackerman's fanzine Imagination! He was rejected for military duty during World War II because of his poor eyesight and Bradbury began his writing career in earnest. Inspired by science-fiction heroes such as Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers, he began to publish science-fiction stories in fanzines in 1938.

After a rejection notice from the pulp magazine Weird Tales, Bradbury submitted Homecoming to the magazine Mademoiselle, which was spotted by a young editorial assistant named Truman Capote. Capote picked the Bradbury manuscript from a slush pile, which led to its publication. Homecoming won a place in the O. Henry Award Stories of 1947.

In UCLA's Powell Library, in a study room with typewriters for rent, Bradbury wrote his classic story of a book burning future, The Fireman, which was about 25,000 words long.

Five ladyfinger firecrackers and then an explosion.

That just about describes the genesis of Fahrenheit 451. Five short stories, written over a period of two or three years, caused me to invest nine dollars and fifty cents in dimes to rent a pay typewriter in a basement library typing room and finish the short novel in just nine days.”

5 short stories written over a period ….

Bonfire, which never sold to any magazine is about the long literary thoughts of a man on the night before the world was coming to an end. Bright Phoenix is about a town librarian threatened by the local patriot bigot. When he takes coffee with the librarian, he encounters Keats, Plato, Einstein, Shakespeare, Lincoln and so on…and realises that the whole town has hidden books by memosizing them. Exiles concerns the characters in the Oz, Tarzan & Alice books. Usher II is a story where the hero collects all the intellectual book burners of the earth and sinks them to drown in a tarn as the second House of Usher vanishes from sight in countless fathoms. Pedestrian, written 42 years later, is about a future when all walking was forbidden, and all pedestrians treated as criminals.

This resulted in Fireman which turned out to be a 25,000 words long novella. It was difficult to sell.

Finally, a young Chicago editor, with no money, bought the book for $450 to be published in issues 2, 3 and 4 of his about to be born magazine. Hugh Hefner was the editor, and the magazine was Playboy, and the rest is history….

Fahrenheit 451 was written during the McCarthy era, and Badbury's claimed motivation for writing the novel has changed multiple times. In a 1956 radio interview, Bradbury said that he wrote the book because of his concerns about the threat of burning books in the United States. In later years, he described the book as a commentary on how mass media reduces interest in reading literature. In a 1994 interview, Bradbury cited political correctness as an allegory for the censorship in the book, calling it “the real enemy these days ... black groups want to control our thinking and you can’t say certain things. The homosexual groups don’t want you to criticize them. It’s thought control and freedom of speech control.” Upon its release, Fahrenheit 451 was a critical success, although it polarised some critics. The novel's subject matter led to its censorship in apartheid South Africa and various schools in the United States. In 1954, Fahrenheit 451 won the American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Literature and the Commonwealth Club of California Gold Medal. It later won the Prometheus Hall of Fame Award in 1984 and a Retro Hugo Award in 2004. Bradbury was honoured with a Spoken Word Grammy nomination for his 1976 audiobook version.

Fahrenheit 451 is set in an unspecified city in the year 2049 (according to Ray Bradbury's Coda), though it is written as if set in a distant future.The earliest editions make clear that it takes place no earlier than the year 1960.

Arundhaty felt that the first turning point in Montag's life was when he met Clarisse and he begins to realise he was not ‘happy’ with the way things were. He needed to save books and not burn them, he realised. Capt Beatty discovers his attempts at saving books and orders his house to be burned down.

Montag is trying to rebel, but he is confused because of his many mental blocks against nonconformity. He has never before deviated from the societal order, and his attempts to establish an individual identity are continually frustrated.

In his desperation and thirst for knowledge, Montag recalls an encounter the previous year with an elderly man in the park. The old man, a retired English professor named Faber, made an impression on Montag because he actually spoke with Montag about real things. Montag remembers that he keeps Faber's phone number in his files of possible book hoarders, and he determines that if anyone can be his teacher and help him understand books, Faber can. Consequently, Montag takes the subway to Faber's home and carries with him a copy of the Bible.

While riding the subway to Faber's house, Montag experiences a moment of self-reflection. He discovers that his smile, “the old burnt-in smile,” has disappeared. He recognises his emptiness and unhappiness. Moreover, he recognises his lack of formal education — what he thinks is his essential ignorance. This sense of helplessness, of ineffectuality, of powerlessness, of his utter inability to comprehend what is in books, overwhelms him, and his mind flashes back to a time when he was a child on the seashore “trying to fill a sieve with sand.” Montag recalls that “the faster he poured [the sand], the faster it sifted through with a hot whispering.” He now has this same feeling of helplessness as he reads the Bible; his mind seems to be a sieve through which the words pass without Montag's comprehending or remembering them. He knows that in a few hours he must give this precious book to Beatty, so he attempts to read and memorise the scriptures — in particular, Jesus' Sermon on the Mount. As he attempts to memorise the passages, however, a loud and brassy advertisement for “Denham's Dental Detergent” destroys his concentration.

Faber is a devotee of the ideas contained in books. He is also concerned with the common good of man. Montag immediately senses Faber's enthusiasm and readily admits his feelings of unhappiness and emptiness. He confesses that his life is missing the values of books and the truths that they teach. Montag then asks Faber to teach him to understand what he reads. At first, Faber views this new teaching assignment as a useless, as well as dangerous, undertaking. His attitude, however, does not deter Faber from launching into such a challenging and exciting task.

Much of what Montag's society tries to control is the self, and part of this effort is through the elimination of books that would cause people to think and imagine. That sort of individualism undermines the state's power and monopoly over thought. The conflict is in play in the subway scene in Fahrenheit 451.

(https:/www.cliffsnotes.com)

radio and ‘televisors’ could never replace books. Saras loved the ‘smell of spices’ in books and smells books to this day. Joe and KumKum's grandson, Gael, Joe said, would smell books when he first got them. KumKum said though many of us have moved to Kindle due to space constraints the physicality of books, holding them in your hand was something that Kindle could not give. Joe though, was a proponent for Kindle when he gave us some features of Kindle which none of us have realised were available, where you can read the comments of other people on the book you are reading and to make comments which would be visible to others. Joe once visited an exhibition of books from the Vatican at Washington DC Library where there were books laid out. The right side was the text of the book itself and the left contained comments on passages by various people. Joe realised the some of the comments came from the pen of saints.

One of the things that Joe found remarkable in contrast to books like 1984 by George Orwell is the far more profound description in Orwell of the ideology and rationale of the government that surveils society. In Fahrenheit 451 we are not told much about the ideological underpinning that makes the government behave the way it does. Instead, we are treated to the lowest level of functionaries of that society, the firemen, burning books. We are kept ignorant of what are the policies motivating the government.

Montag, though one of the firemen entrusted with burning books, decides with his wife Millie that it’s the firemen who have to be burned, not the books:

I suddenly realized I didn’t like them at all, and I didn’t like myself at all any more. And I thought maybe it would be best if the firemen themselves were burnt.

In short, Montag turns from loyal book-buner to rebel in this passage, and casts off his enslavement to the system in which he has been trapped thus far. That’s why Joe chose this short passage.

Ray Bradbury sold a shorter version, a novel of 25,000 words to Playboy magazine for its Mar 1954 issue. Over its history Playboy has published such prominent American authors as Nabokov, Baldwin, Updike, Wodehouse, Mailer, Oates, and so on. As everyone knows, the very first issue in Dec 1953 printed a nude Marilyn Monroe in the centrefold.

Bradbury in a note about his creation of the novel confesses how he learned about the resources of the UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) library – that he could use typewriters in the basement for ten cents per half hour. The library itself was free and

“I ran up and down the stairs and in and out of the stacks, grabbing books off the shelf, trying to find proper quotes to put in the book … What a wonderful experience it was to be in the library basement to dash up and down the stairs reinvigorating myself with the touch and smell of books that I know and books that I did not know until that moment.”

Public libraries that are dotted all over America, from the smallest villages of a few thousand inhabitants to the multiple branch libraries in big cities, constitute one of its chief jewels – entirely free. They make a radical proposition – that learning, knowledge and curiosity are for everyone. You can a good account at:

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/dec/28/usa-public-libraries

Fahrenheit 451 is considered a dystopian novel set in an unspecified city in the US in the year 2049. The novel was widely appreciated when first published in 1953, and is considered an important literary work of American literature. Today the book is often included by many American high schools in their recommended reading lists. KumKum’s granddaughter Elsa had to read the book in 2021 in her 10th grade literature class. KumKum happened to be with her family that summer, and she was asked to read the book along with her. That's when KumKum became acquainted first with Fahrenheit 451.

When KRG's list included the book for its January 2023 reading it was KumKum’s second encounter with the book.

Fahrenheit 451 tells a story of a fictional town where firemen took upon themselves the odious task of setting fire to books, and burning houses that stored them, upon the orders of the government. Strangely enough the firemen lit fires rather than snuffing them out.

We meet an old woman who chose to light a match and immolate herself along with her books rather than watch the firemen burn her treasured collection of books.

The old woman’s brave and unexpected action affected Guy Montag, a fireman and protagonist of the novel. The intrusive questioning of Clarisse also made him think. KumKum chose to read the passage that describes the episode of the old woman.

"You weren't hurting anyone, you were hurting only things! And since things don't scream or whimper, as this woman might begin to scream, and cry out, there was nothing to tease your conscience later. You were simply cleaning up. Janitorial work, essentially. Everything to its proper place. Quick with the Kerosene! Who's got a match!"

The phrase “Parlor Wall” made KumKum laugh, for it had a personal connection. In the book it referred to the entertainment in the living room, with large televisions filling the wall. When KumKum recently moved to her flat and she had to install a TV on the wall of her living room which became her ‘parlour wall.’

The portion Saras chose to read shows Montag meeting Granger and the rest of the “rebels" and discovering that there are many among them who have memorised whole books so that when the war that was coming ended, these people would be there to bring back all this lost knowledge to the people. They keep a low profile because if they are killed that knowledge dies with them. This knowledge bank is spread all over the country. It reminded Saras of the oral tradition of transmitting knowledge in ancient India where whole texts of the Vedas etc were taught to students in the Gurukul system by memorising them. In fact, the Indian school system relied heavily on rote learning till very recent times.

Fahrenheit 451 tells the story of a future time, when books are being burnt, and people are so absorbed by television that they do not notice the value of what they are losing. Almost seven decades later, as we read and discussed the book, it is indeed a relevant topic in our present situation. But more than television, it is Internet and related technology that has changed the habits and minds of people. The youth of today are more interested in Internet gaming than reading or even music.

Shoba read the part where the character Faber is introduced to the reader. Montag had had a chance meeting with him in a park. A retired college professor, Faber plays a crucial role in helping Montag escape, when he is on the run after killing Beatty. In the passage, Faber tells Montag that there are no copies left of Shakespeare or Plato. Montag thinks it is possible that what he has with him is the last surviving copy of the Bible. The story has been written in a style that draws the reader into the tension and suspense that follows Montag’s change of mind and his escape from the Hound.

Thomo's portion was taken from the end of the book. It describes a scene where Montag meets up with Granger and the others. Everyone has committed to memory one great book so that it would not be lost to humanity. Each person is known by the books they have learned by heart for instance, Mathew, Mark, Luke and John are the names given to those who have memorised the Gospels.

Thomo was reminded of a portion in Alex, Hailey's book Roots in which a ‘griot’, an oral chronicler, in a village in Gambia starts relating – over a period of 3 days – without break or repetition – the history of the tribe all the way back till the narration of Kunta Kinte (Hailey's ancestor) going off to chop wood and never being seen again. Saras stated that it was the tradition in India to commit to memory huge portions of text from the puranas, if not the entirety of the book. Joe said that Eastern Europe had a tradition of memorizing poems as quite a few of them were banned. KumKum mentioned the fate of the poet Anna Akhmatova who is a favourite of her's. She never had her poems printed or even written out by hand in Russia, for fear it would incriminate persons found with copies. The poems were memorised and printed in the West. Joe had read one of her poems at a poetry session in KRG.

“The difference between the man who just cuts lawns and a real gardener is in the touching, he said. The lawn-cutter might just as well not have been there at all; the gardener will be there a lifetime.”

These lines from Zakia's reading reminded most KRG members of KumKum, who is a keen gardener.

They crashed the front door and grabbed at a woman, though she was not running, she was not trying to escape. She was only standing, weaving from side to side, her eyes fixed upon a nothingness in the wall as if they had struck her a terrible blow upon the head. Her tongue was moving in her mouth, and her eyes seemed to be trying to remember something, and then they remembered and her tongue moved again:

‘“Play the man, Master Ridley; we shall this day light such a candle, by God’s grace, in England, as I trust shall never be put out.”’

‘Enough of that!’ said Beatty. ‘Where are they?’

He slapped her face with amazing objectivity and repeated the question. The old woman’s eyes came to a focus upon Beatty. ‘You know where they are or you wouldn’t be here,’ she said.

Stoneman held out the telephone alarm card with the complaint signed in telephone duplicate on the back:

‘Have reason to suspect attic; 11 No. Elm, City. E.B.’

‘That would be Mrs Blake, my neighbour,’ said the woman, reading the initials.

‘All right, men, let’s get ’em!’

Next thing they were up in musty blackness, swinging silver hatchets at doors that were, after all, unlocked, tumbling through like boys all rollick and shout. ‘Hey!’ A fountain of books sprang down upon Montag as he climbed shuddering up the sheer stair-well. How inconvenient! Always before it had been like snuffing a candle. The police went first and adhesive-taped the victim’s mouth and bandaged him off into their glittering beetle cars, so when you arrived you found an empty house. You weren’t hurting anyone, you were hurting only things! And since things really couldn’t be hurt, since things felt nothing, and things don’t scream or whimper, as this woman might begin to scream and cry out, there was nothing to tease your conscience later. You were simply cleaning up. Janitorial work, essentially. Everything to its proper place. Quick with the kerosene! Who’s got a match!

But now, tonight, someone had slipped. This woman was spoiling the ritual. The men were making too much noise, laughing, joking to cover her terrible accusing silence below. She made the empty rooms roar with accusation and shake down a fine dust of guilt that was sucked in their nostrils as they plunged about. It was neither cricket nor correct. Montag felt an immense irritation. She shouldn’t be here, on top of everything! (409 words)

p. 50 Devika

Montag’s hand closed like a mouth, crushed the book with wild devotion, with an insanity of mindlessness to his chest. The men above were hurling shovelfuls of magazines into the dusty air. They fell like slaughtered birds and the woman stood below, like a small girl, among the bodies.

Montag had done nothing. His hand had done it all, his hand, with a brain of its own, with a conscience and a curiosity in each trembling finger, had turned thief. Now, it plunged the book back under his arm, pressed it tight to sweating armpit, rushed out empty, with a magician’s flourish! Look here! Innocent! Look!

He gazed, shaken, at that white hand. He held it way out, as if he were far-sighted. He held it close, as if he were blind.

‘Montag!’

He jerked about.

‘Don’t stand there, idiot!’

The books lay like great mounds of fishes left to dry. The men danced and slipped and fell over them. Titles glittered their golden eyes, falling, gone.

‘Kerosene!’

They pumped the cold fluid from the numbered 451 tanks strapped to their shoulders. They coated each book, they pumped rooms full of it.

They hurried downstairs, Montag staggered after them in the kerosene fumes.

‘Come on, woman!’

The woman knelt among the books, touching the drenched leather and cardboard, reading the gilt titles with her fingers while her eyes accused Montag.

‘You can’t ever have my books,’ she said.

‘You know the law,’ said Beatty. ‘Where’s your common sense? None of these books agree with each other. You’ve been locked up here for years with a regular damned Tower of Babel. Snap out of it! The people in those books never lived. Come on now!’

She shook her head.

‘The whole house is going up,’ said Beatty. The men walked clumsily to the door. They glanced back at Montag, who stood near the woman.

‘You’re not leaving her here?’ he protested.

‘She won’t come.’ ‘Force her then!’

Beatty raised his hand in which was concealed the igniter. ‘We’re due back at the house. Besides, these fanatics always try suicide; the pattern’s familiar.’

Montag placed his hand on the woman’s elbow. ‘You can come with me.’

‘No,’ she said. ‘Thank you, anyway.’

‘I’m counting to ten,’ said Beatty. ‘One. Two.’

‘Please,’ said Montag.

‘Go on,’ said the woman.

‘Three. Four.’ ‘Here.’ Montag pulled at the woman.

The woman replied quietly, ‘I want to stay here.’

‘Five. Six.’

‘You can stop counting,’ she said. She opened the fingers of one hand slightly and in the palm of the hand was a single slender object.

An ordinary kitchen match.

The sight of it rushed the men out and down away from the house. Captain Beatty, keeping his dignity, backed slowly through the front door, his pink face burnt and shiny from a thousand fires and night excitements. God, thought Montag, how true! Always at night the alarm comes. Never by day! Is it because the fire is prettier by night? More spectacle, a better show? The pink face of Beatty now showed the faintest panic in the door. The woman’s hand twitched on the single match-stick. The fumes of kerosene bloomed up about her. Montag felt the hidden book pound like a heart against his chest.

‘Go on,’ said the woman, and Montag felt himself back away and away out of the door, after Beatty, down the steps, across the lawn, where the path of kerosene lay like the track of some evil snail.

On the front porch where she had come to weigh them quietly with her eyes, her quietness a condemnation, the woman stood motionless.

Beatty flicked his fingers to spark the kerosene.

He was too late. Montag gasped.

The woman on the porch reached out with contempt for them all, and struck the kitchen match against the railing.

People ran out of houses all down the street all down the street.

(650 words)

p. 86 Joe

‘Millie!’ he said. ‘Listen. Give me a second, will you? We can’t do anything. We can’t burn these. I want to look at them, at least look at them once. Then if what the Captain says is true, we’ll burn them together, believe me, we’ll burn them together. You must help me.’ He looked down into her face and took hold of her chin and held her firmly. He was looking not only at her, but for himself and what he must do, in her face. ‘Whether we like this or not, we’re in it. I’ve never asked for much from you in all these years, but I ask it now, I plead for it. We’ve got to start somewhere here, figuring out why we’re in such a mess, you and the medicine at night, and the car, and me and my work. We’re heading right for the cliff, Millie. God, I don’t want to go over. This isn’t going to be easy. We haven’t anything to go on, but maybe we can piece it out and figure it and help each other. I need you so much right now, I can’t tell you. If you love me at all you’ll put up with this, twenty-four, forty-eight hours, that’s all I ask, then it’ll be over. I promise, I swear! And if there is something here, just one little thing out of a whole mess of things, maybe we can pass it on to someone else.’

She wasn’t fighting any more, so he let her go. She sagged away from him and slid down the wall, and sat on the floor looking at the books. Her foot touched one and she saw this and pulled her foot away.

‘That woman, the other night, Millie, you weren’t there. You didn’t see her face. And Clarisse. You never talked to her. I talked to her. And men like Beatty are afraid of her. I can’t understand it. Why should they be so afraid of someone like her? But I kept putting her alongside the firemen in the house last night, and I suddenly realized I didn’t like them at all, and I didn’t like myself at all any more. And I thought maybe it would be best if the firemen themselves were burnt.’ (381 words)

p. 97 Shoba

The old man admitted to being a retired English professor who had been thrown out upon the world forty years ago when the last liberal arts college shut for lack of students and patronage. His name was Faber, and when he finally lost his fear of Montag, he talked in a cadenced voice, looking at the sky and the trees and the green park, and when an hour had passed he said something to Montag and Montag sensed it was a rhymeless poem. Then the old man grew even more courageous and said something else and that was a poem, too. Faber held his hand over his left coat-pocket and spoke these words gently, and Montag knew if he reached out, he might pull a book of poetry from the man’s coat. But he did not reach out. His hands stayed on his knees, numbed and useless. ‘I don’t talk things, sir,’ said Faber. ‘I talk the meaning of things. I sit here and know I’m alive.’

That was all there was to it, really. An hour of monologue, a poem, a comment, and then without even acknowledging the fact that Montag was a fireman, Faber with a certain trembling, wrote his address on a slip of paper. ‘For your file,’ he said, ‘in case you decide to be angry with me.’

‘I’m not angry,’ Montag said, surprised.

Mildred shrieked with laughter in the hall. Montag went to his bedroom closet and flipped through his file-wallet to the heading: FUTURE INVESTIGATIONS (?). Faber’s name was there. He hadn’t turned it in and he hadn’t erased it.

He dialled the code on a secondary phone. The phone on the far end of the line called Faber’s name a dozen times before the professor answered in a faint voice. Montag identified himself and was met with a lengthy silence. ‘Yes, Mr Montag?’

‘Professor Faber, I have a rather odd question to ask. How many copies of the Bible are left in this country?’

‘I don’t know what you’re talking about!’

‘I want to know if there are any copies at all.’

‘This is some sort of a trap! I can’t talk to just anyone on the phone!’

‘How many copies of Shakespeare and Plato?’

‘None! You know as well as I do. None!’

Faber hung up.

Montag put down the phone. None. A thing he knew of course from the firehouse listings. But somehow he had wanted to hear it from Faber himself.

In the hall Mildred’s face was suffused with excitement. ‘Well, the ladies are coming over!’

Montag showed her a book. ‘This is the Old and New Testament, and –’

‘Don’t start that again!’

‘It might be the last copy in this part of the world.’

‘You’ve got to hand it back tonight, don’t you know? Captain Beatty knows you’ve got it, doesn’t he?’

‘I don’t think he knows which book I stole. But how do I choose a substitute? Do I turn in Mr Jefferson? Mr Thoreau? Which is least valuable? If I pick a substitute and Beatty does know which book I stole, he’ll guess we’ve an entire library here!’

Mildred’s mouth twitched. ‘See what you’re doing? You’ll ruin us! Who’s more important, me or that Bible?’ She was beginning to shriek now, sitting there like a wax doll melting in its own heat.

He could hear Beatty’s voice. ‘Sit down, Montag. Watch. Delicately, like the petals of a flower. Light the first page, light the second page. Each becomes a black butterfly. Beautiful, eh? Light the third page from the second and so on, chain-smoking, chapter by chapter, all the silly things the words mean, all the false promises, all the second-hand notions and time-worn philosophies.’ There sat Beatty, perspiring gently, the floor littered with swarms of black moths that had died in a single storm.

Mildred stopped screaming as quickly as she started. Montag was not listening. ‘There’s only one thing to do,’ he said. ‘Some time before tonight when I give the book to Beatty, I’ve got to have a duplicate made.’ (677 words)

p. 105 Geetha

Faber’s hands itched on his knees. ‘May I?’

‘Sorry.’ Montag gave him the book.

‘It’s been a long time. I’m not a religious man. But it’s been a long time.’ Faber turned the pages, stopping here and there to read. ‘It’s as good as I remember. Lord, how they’ve changed it in our “parlours” these days. Christ is one of the “family” now. I often wonder if God recognizes His own son the way we’ve dressed him up, or is it dressed him down? He’s a regular peppermint stick now, all sugar-crystal and saccharine when he isn’t making veiled references to certain commercial products that every worshipper absolutely needs.’ Faber sniffed the book. ‘Do you know that books smell like nutmeg or some spice from a foreign land? I loved to smell them when I was a boy. Lord, there were a lot of lovely books once, before we let them go.’ Faber turned the pages. ‘Mr Montag, you are looking at a coward. I saw the way things were going, a long time back. I said nothing. I’m one of the innocents who could have spoken up and out when no one would listen to the “guilty”, but I did not speak and thus became guilty myself. And when finally they set the structure to burn the books, using the firemen, I grunted a few times and subsided, for there were no others grunting or yelling with me, by then. Now, it’s too late.’ Faber closed the Bible. ‘Well – suppose you tell me why you came here?’

‘Nobody listens any more. I can’t talk to the walls because they’re yelling at me. I can’t talk to my wife; she listens to the walls. I just want someone to hear what I have to say. And maybe if I talk long enough, it’ll make sense. And I want you to teach me to understand what I read.’

Faber examined Montag’s thin, blue-jowled face. ‘How did you get shaken up? What knocked the torch out of your hands?’

‘I don’t know. We have everything we need to be happy, but we aren’t happy. Something’s missing. I looked around. The only thing I positively knew was gone was the books I’d burned in ten or twelve years. So I thought books might help.’

‘You’re a hopeless romantic,’ said Faber. ‘It would be funny if it were not serious. It’s not books you need, it’s some of the things that once were in books. The same things could be in the “parlour families” today. The same infinite detail and awareness could be projected through the radios and televisors, but are not. No, no, it’s not books at all you’re looking for! Take it where you can find it, in old phonograph records, old motion pictures, and in old friends; look for it in nature and look for it in yourself. Books were only one type of receptacle where we stored a lot of things we were afraid we might forget. There is nothing magical in them at all. The magic is only in what books say, how they stitched the patches of the universe together into one garment for us. Of course you couldn’t know this, of course you still can’t understand what I mean when I say this. You are intuitively right, that’s what counts. Three things are missing.

‘Number one: Do you know why books such as this are so important? Because they have quality. And what does the word quality mean? To me it means texture. This book has pores. It has features. This book can go under the microscope. You’d find life under the glass, streaming past in infinite profusion. The more pores, the more truthfully recorded details of life per square inch you can get on a sheet of paper, the more “literary” you are. That’s my definition, anyway. Telling detail. Fresh detail. The good writers touch life often. The mediocre ones run a quick hand over her. The bad ones rape her and leave her for the flies. (672 words)

p. 110 Pamela

Montag leaned forward. ‘This afternoon I thought that if it turned out that books were worth while, we might get a press and print some extra copies –’

‘We?’

‘You and I.’

‘Oh, no!’ Faber sat up.

‘But let me tell you my plan –’

‘If you insist on telling me, I must ask you to leave.’

‘But aren’t you interested?’

‘Not if you start talking the sort of talk that might get me burnt for my trouble. The only way I could possibly listen to you would be if somehow the fireman structure itself could be burnt. Now if you suggest that we print extra books and arrange to have them hidden in firemen’s houses all over the country, so that seeds of suspicion would be sown among these arsonists, bravo, I’d say!’

‘Plant the books, turn in an alarm, and see the firemen’s houses burn, is that what you mean?’

Faber raised his brows and looked at Montag as if he were seeing a new man. ‘I was joking.’

‘If you thought it would be a plan worth trying, I’d have to take your word it would help.’

‘You can’t guarantee things like that! After all, when we had all the books we needed, we still insisted on finding the highest cliff to jump off. But we do need a breather. We do need knowledge. And perhaps in a thousand years we might pick smaller cliffs to jump off. The books are to remind us what asses and fools we are. They’re Caesar’s praetorian guard, whispering as the parade roars down the avenue, “Remember, Caesar, thou art mortal.” Most of us can’t rush around, talking to everyone, know all the cities of the world, we haven’t time, money or that many friends. The things you’re looking for, Montag, are in the world, but the only way the average chap will ever see ninety-nine per cent of them is in a book. Don’t ask for guarantees. And don’t look to be saved in any one thing, person, machine, or library. Do your own bit of saving, and if you drown, at least die knowing you were headed for shore.’ (360 words)

p. 179 Arundhaty

He was three hundred yards downstream when the Hound reached the river. Overhead the great racketing fans of the helicopters hovered. A storm of light fell upon the river and Montag dived under the great illumination as if the sun had broken the clouds. He felt the river pull him further on its way, into darkness. Then the lights switched back to the land, the helicopters swerved over the city again, as if they had picked up another trail. They were gone. The Hound was gone. Now there was only the cold river and Montag floating in a sudden peacefulness, away from the city and the lights and the chase, away from everything. He felt as if he had left a stage behind and many actors.

He felt as if he had left the great seance and all the murmuring ghosts. He was moving from an unreality that was frightening into a reality that was unreal because it was new.

The black land slid by and he was going into the country among the hills. For the first time in a dozen years the stars were coming out above him, in great processions of wheeling fire. He saw a great juggernaut of stars form in the sky and threaten to roll over and crush him.

He floated on his back when the valise filled and sank; the river was mild and leisurely, going away from the people who ate shadows for breakfast and steam for lunch and vapours for supper. The river was very real; it held him comfortably and gave him the time at last, the leisure, to consider this month, this year, and a lifetime of years. He listened to his heart slow. His thoughts stopped rushing with his blood.

He saw the moon low in the sky now. The moon there, and the light of the moon caused by what? By the sun, of course. And what lights the sun? Its own fire. And the sun goes on, day after day, burning and burning. The sun and time. The sun and time and burning. Burning. The river bobbled him along gently. Burning. The sun and every clock on the earth. It all came together and became a single thing in his mind. After a long time of floating on the land and a short time of floating in the river he knew why he must never burn again in his life.

The sun burned every day. It burned Time. The world rushed in a circle and turned on its axis and time was busy burning the years and the people anyway, without any help from him. So if he burnt things with the firemen, and the sun burnt Time, that meant that everything burned!

One of them had to stop burning. The sun wouldn’t, certainly. So it looked as if it had to be Montag and the people he had worked with until a few short hours ago. Somewhere the saving and the putting away had to begin again and someone had to do the saving and keeping, one way or another, in books, in records, in people’s heads, any way at all so long as it was safe, free from moths, silver-fish, rust and dry-rot, and men with matches. The world was full of burning of all types and sizes. (554 words)

p. 192 Thomo

Granger touched Montag's arm. "Welcome back from the dead." Montag nodded. Granger went on. "You might as well know all of us, now. This is Fred Clement, former occupant of the Thomas Hardy chair at Cambridge in the years before it became an Atomic Engineering School. This other is Dr. Simmons from U.C.L.A., a specialist in Ortega y Gasset; Professor West here did quite a bit for ethics, an ancient study now, for Columbia University quite some years ago. Reverend Padover here gave a few lectures thirty years ago and lost his flock between one Sunday and the next for his views. He's been bumming with us some time now. Myself: I wrote a book called The Fingers in the Glove; the Proper Relationship between the Individual and Society, and here I am! Welcome, Montag! "

"I don't belong with you," said Montag, at last, slowly. "I've been an idiot all the way."

"We're used to that. We all made the right kind of mistakes, or we wouldn't be here. When we were separate individuals, all we had was rage. I struck a fireman when he came to burn my library years ago. I've been running ever since. You want to join us, Montag?"

Yes

What have you to offer?"

"Nothing. I thought I had part of the Book of Ecclesiastes and maybe a little of Revelation, but I haven't even that now."

"The Book of Ecclesiastes would be fine. Where was it?"

"Here," Montag touched his head.

"Ah," Granger smiled and nodded.

"What's wrong? Isn't that all right?" said Montag.

"Better than all right; perfect!" Granger turned to the Reverend.

"Do we have a Book of Ecclesiastes?"

"One. A man named Harris of Youngstown."

"Montag." Granger took Montag's shoulder firmly. "Walk carefully. Guard your health. If anything should happen to Harris, you are the Book of Ecclesiastes. See how important you've become in the last minute!"

"But I've forgotten!"

"No, nothing's ever lost. We have ways to shake down your clinkers for you."

"But I've tried to remember!"

"Don't try. It'll come when we need it. All of us have photographic memories, but spend a lifetime learning how to block off the things that are really in there. Simmons here has worked on it for twenty years and now we've got the method down to where we can recall anything that's been read once. Would you like, some day, Montag, to read Plato's Republic?"

"Of course!"

"I am Plato's Republic. Like to read Marcus Aurelius? Mr. Simmons is Marcus."

"How do you do?" said Mr. Simmons.

"Hello," said Montag.

"I want you to meet Jonathan Swift, the author of that evil political book, Gulliver's Travels! And this other fellow is Charles Darwin, and-this one is Schopenhauer, and this one is Einstein, and this one here at my elbow is Mr. Albert Schweitzer, a very kind philosopher indeed. Here we all are, Montag. Aristophanes and Mahatma Gandhi and Gautama Buddha and Confucius and Thomas Love Peacock and Thomas Jefferson and Mr. Lincoln, if you please. We are also Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John."

Everyone laughed quietly.

"It can't be," said Montag. (520 words)

p. 194 Saras (continuing from Thomo’s passage above)

‘It is,’ replied Granger, smiling. ‘We’re book-burners, too. We read the books and burnt them, afraid they’d be found. Micro-filming didn’t pay off; we were always travelling, we didn’t want to bury the film and come back later. Always the chance of discovery. Better to keep it in the old heads, where no one can see it or suspect it. We are all bits and pieces of history and literature and international law, Byron, Tom Paine, Machiavelli, or Christ, it’s here. And the hour is late. And the war’s begun. And we are out here, and the city is there, all wrapped up in its own coat of a thousand colours. What do you think, Montag?’

‘I think I was blind trying to do things my way, planting books in firemen’s houses and sending in alarms.’

‘You did what you had to do. Carried out on a national scale, it might have worked beautifully. But our way is simpler and, we think, better. All we want to do is keep the knowledge we think we will need, intact and safe. We’re not out to incite or anger anyone yet. For if we are destroyed, the knowledge is dead, perhaps for good. We are model citizens, in our own special way; we walk the old tracks, we lie in the hills at night, and the city people let us be. We’re stopped and searched occasionally, but there’s nothing on our persons to incriminate us. The organization is flexible, very loose, and fragmentary. Some of us have had plastic surgery on our faces and fingerprints. Right now we have a horrible job; we’re waiting for the war to begin and, as quickly, end. It’s not pleasant, but then we’re not in control, we’re the odd minority crying in the wilderness. When the war’s over, perhaps we can be of some use in the world.’

‘Do you really think they’ll listen then?’

‘If not, we’ll just have to wait. We’ll pass the books on to our children, by word of mouth, and let our children wait, in turn, on the other people. A lot will be lost that way, of course. But you can’t make people listen. They have to come round in their time, wondering what happened and why the world blew up under them. It can’t last.’

‘How many of you are there?’

‘Thousands on the roads, the abandoned railtracks, tonight, bums on the outside, libraries inside. It wasn’t planned, at first. Each man had a book he wanted to remember, and did. Then, over a period of twenty years or so, we met each other, travelling, and got the loose network together and set out a plan. The most important single thing we had to pound into ourselves was that we were not important, we mustn’t be pedants; we were not to feel superior to anyone else in the world. We’re nothing more than dust-jackets for books, of no significance otherwise. Some of us live in small towns. Chapter One of Thoreau’s Walden in Green River, Chapter Two in Willow Farm, Maine. Why, there’s one town in Maryland, only twenty-seven people, no bomb’ll ever touch that town, is the complete essays of a man named Bertrand Russell. Pick up that town, almost, and flip the pages, so many pages to a person. And when the war’s over, some day, some year, the books can be written again, the people will be called in, one by one, to recite what they know and we’ll set it up in type until another Dark Age, when we might have to do the whole damn thing over again. But that’s the wonderful thing about man; he never gets so discouraged or disgusted that he gives up doing it all over again, because he knows very well it is important and worth the doing.’ (639 words)

p. 199 Zakia

He was part of us and when he died, all the actions stopped dead and there was no one to do them just the way he did. He was individual. He was an important man. I’ve never gotten over his death. Often I think, what wonderful carvings never came to birth because he died. How many jokes are missing from the world, and how many homing pigeons untouched by his hands. He shaped the world. He did things to the world. The world was bankrupted of ten million fine actions the night he passed on.’

Montag walked in silence. ‘Millie, Millie,’ he whispered. ‘Millie.’

‘What?’

‘My wife, my wife. Poor Millie, poor Millie. I can’t remember anything. I think of her hands but I don’t see them doing anything at all. They just hang there at her sides or they lie there on her lap or there’s a cigarette in them, but that’s all.’

Montag turned and glanced back. What did you give to the city, Montag?

Ashes.

What did the others give to each other?

Nothingness.

No comments:

Post a Comment