Slaughterhouse-Five First Edition, First Printing

One of the strange facets of the novel is that there is no vivid description of the central event, the Dresden fire-bombing carried out by American and British bombers on the nights of Feb 13-15, 1945 when hundreds of planes dropped thousands of tons of bombs and incendiary explosives that destroyed the city of Dresden, and killed tens of thousands of its inhabitants.

Vonnegut perhaps found himself unequal to describing the horror directly that was visited on the city when he was there. They went down two floors below the pavement into the big meat locker Schlachthöf-funf. Vonnegut said “It was cool there, with cadavers hanging all around. When we came up the city was gone.”

He continues:

“Every day we walked into the city and dug into basements and shelters to get the corpses out, as a sanitary measure. When we went into them, a typical shelter, an ordinary basement usually, looked like a streetcar full of people who’d simultaneously had heart failure. Just people sitting there in their chairs, all dead. A firestorm is an amazing thing. It doesn’t occur in nature. It’s fed by the tornadoes that occur in the midst of it and there isn’t a damned thing to breathe. We brought the dead out. They were loaded on wagons and taken to parks, large, open areas in the city which weren’t filled with rubble. The Germans got funeral pyres going, burning the bodies to keep them from stinking and from spreading disease.”

This is the view we do NOT get from the novel. Instead it is irony, satire, the gentle comedy of a soldier who has lost his marbles in the war, and hallucinates about aliens who have captured and taken him to their distant planet, and shown him how to do time travel, which allows him to go back and forth in an imagined fourth dimension.

The trauma of Dresden is filtered through the PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) of an American enlisted soldier, Billy Pilgrim. There is absolutely nothing about the trauma of the civilians who were burnt alive in Dresden, while Billy Pilgrim and his cohorts were cooling off two floors below in the cellar of the meat locker.

Of course, there is a lot of humour which Vonnegut extracts from the crazy situations in which war puts people:

“Billy looked inside the latrine. The wailing was coming from in there. The place was crammed with Americans who had taken their pants down. The welcome feast had made them as sick as volcanoes. The buckets were full or had been kicked over.

An American near Billy wailed that he had excreted everything but his brains.

Moments later he said, 'There they go, there they go.' He meant his brains.”

Some have called it an anti-war novel. Perhaps it is better to characterise it as a novel that shows how people who have to endure war come out of it twisted and shattered by its horrors, and will possibly lose the equanimity needed to live a normal life, even if they end up on the victorious side. It is doubtful that Vonnegut takes a negative view of WWII at all, seeing as he enlisted and joined the war on his own. Recall that WWII in the European theatre was seen as pitting the forces of good against the Nazi evil.

These two pics will suffice to capture what Dresden was for centuries, and what it became within two days in February 1945.

Full Account and Record of the Reading

Intro to the Novel by Geetha:

Geetha said she had a difficulty again choosing a book, and generally takes Joe's advice on the quality of book and went in search of another book, wanting it to be a better.

Actually it was Kavita who was supposed to select the novel this time. Thomo came up with this writer Kurt Vonnegut, about whom Geetha had not heard , but that’s nothing new as she has not read many very famous authors. It is a gift for Geetha to be part of this group and be exposed to authors that the world talks about. Her son, Rahul, read it while he was in college, he said.

Our mindsets in the present are so different that it takes us a while to adjust to the pattern and the rhythm of the Vonnegut and his style of writing and thinking. It took her a while but she actually grew into the book.

She had much help from her husband, Thomo.

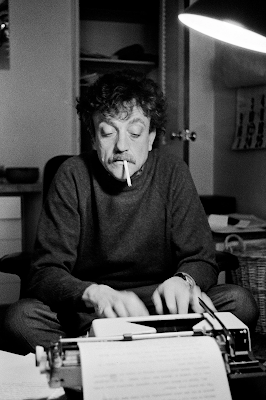

Photograph by Santi Visalli, The New Yorker

Kurt Vonnegut was an American writer and humorist, known for his satirical and darkly humorous novels, novels of the kind that Geetha felt she had liking for.

Vonnegut was born on 11th November, 1922, and in a career spanning over 50 years, he published 14 novels, three short story collections, five plays, and five nonfiction works. Further collections have been published after his death. Born and raised in Indianapolis, Vonnegut attended Cornell University, but withdrew in January 1943 and enlisted in the U.S. Army during World War II. As part of his training for the war, he studied mechanical engineering at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) and the University of Tennessee.

Deployed to Europe, he fought in World War II and was captured by the Germans during the Battle of the Bulge and interned in Dresden, where he survived the Allied bombing of the city in a meat locker of the slaughterhouse where he had been imprisoned.

Vonnegut's first novel was The Piano Player, was well-received by critics, but was not a commercial success.

In the nearly 20 years that followed, he published several novels that were well-regarded, two of which, The Sirens of Titan and The Cat's Cradle, were nominated for the Hugo Award for Best Science Fiction or Fantasy Novel of the Year.

He also published a short story collection titled Welcome to the Monkey House in 1968.

But his breakthrough was his commercially (and critically) successful sixth novel, Slaughterhouse-Five, brought out in the very next year. The book's anti-war sentiment resonated with its readers amidst the ongoing Vietnam War, and its reviews were generally positive.

Slaughterhouse-Five, also known as The Children's Crusade, Duty Dance with Death, immediately rose to the top of the New York Times bestseller list and made Vonnegut famous.

On May 14, 1944, Vonnegut returned home on leave for the Mother's Day weekend to discover that his mother, Edith, had committed suicide the previous night by overdosing on sleeping pills. Possible factors that contributed to Edith Vonnegut's suicide include the family's loss of wealth and status, Vonnegut's deployment overseas, and her own lack of success as a writer. She was inebriated at the time and under the influence of prescription drugs.

Vonnegut struggled as a writer till Slaughterhouse-Five, which solidified his career as an anti-war writer and a symbol of pacifism throughout the 70s. Today, the novel ranks on lists of the hundred best English language books ever written. Vonnegut was a humanist and a free thinker, and once described himself as a Christ-loving atheist. He was not a Christian, but did not disdain those who sought the comfort of religion; he hailed church associations as a type of extended family.

His wife, Jane, embraced Christianity and then left home with five of their six children.

He taught briefly at Harvard as a lecturer in creative writing and was a distinguished professor at the City College of New York during the 1973-74 academic year.

Thomo said a little bit about the bombing of Dresden:

The bombing of Dresden was, he said, a crazy irrational act because Dresden was not an industrial zone; it was mainly known for its Dresden Porcelain than anything else. It was a very beautiful city, they say. The bombing of Dresden was a joint British and American firebombing attack using 772 Lancaster heavy bombers of the RAF and 525 B-17 Flying Fortress bombers of the USAF. They dropped more than 3,900 tons of heavy bombs and incendiary explosives on Dresden, destroying more than 1,600 acres of the city and killing 25,000 people.

Vonnegut himself, being a POW in Dresden, experienced the destruction of Dresden firsthand. That is what has propelled him to write this book.

In his youth Thomo read of the Children's Crusade, where youngsters in the Middle Ages in Europe were tricked into going to Jerusalem in a crusade to get back the Holy Land from the Saracens. They went, and none of them returned to Europe.

Vonnegut in this novel alleges says that two monks had concocted this scheme, and their idea was to sell the boys as slaves. According to the book, one ship load landed in Genoa by mistake, where the people gave some money and food and sent the boys back home. Nobody knows what happened to the rest.

The scheme had the blessings of the Pope, apparently, who didn't know the nefarious plans of the two monks. Those who joined the war were children, very young, and in that respect not much different from the young lads who have gone to the front in all wars.

Vonnegut was an intellectual. It's well worth a read that we know the minds of such people. His brother was an environmental scientist. Their minds were really elevated.

If we read it to the end it'll give us the whole gist of the author's approach to the event. And then too it's real, it's his story of the war.

Arundhaty

Arundhaty said the book is an account of the capture and incarceration by the Germans during the last year of World War II of the American soldier Billy Pilgrim.

Geetha told Arundhaty that Thomo selected the book and Joe approved. She had a question, the two men can answer any time during this session, namely: is there a specific idea behind the story other than the war and the time travel of the protagonist to the planet Tralfamadore? Why does time travel come into this story?

There have been so many war stories all over, and so many real-life accounts of the World War II, the bloodiest conflict in history (40m to 50m deaths, the vast majority in the Soviet Union which bore the brunt of the Wehrmacht’s onslaught). But in this particular book which has become so famous, it is true that Vonnegut wrote against the war. The passage Arundhaty selected actually relates to the alternate name of this particular book (The Children's Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death). The only part which really made sense to Arundhaty is about children being used for wars – which is the reason why she selected her particular passage. It is one of the points that he makes that people glorify war and but in reality it's mostly barely grown children who are being sacrificed at the altar of war. It is happening today too – in Gaza and elsewhere. It's the children who are suffering. In Vietnam it was the young boys who were drafted and sent to a war the generals knew was futile. This has been going on for years and one supposes it will always go on.

Regarding Arundhaty’s question about the role of science fiction, time travel, and planet Trafalmadore in Vonnegut's novel we may say they connect events in Billy Pilgrim's life and enable philosophical discussions about the nature of death and time. The Tralfamadorians view time as circular and present all at once with no past and no future; therefore, they reject human ideas of free will. Billy is made to strip and get rid of his free will, much like the German soldiers who imprisoned him during WWII.

Tralfamadore is a utopian world, where there are no emotions or sadness. Vonnegut seems to use science fiction as an escape route for Billy from the severe mental trauma of war. But Salman Rushdie has anther take on this in his 2019 article in The New Yorker, What Kurt Vonnegut’s “Slaughterhouse-Five” Tells Us Now. He says:

“It seems obvious, at least to this reader, that there is a mischievous ironic intelligence at work here, that there is no reason for us to assume that the rejection of free will by aliens resembling toilet plungers is a rejection also made by their creator (Vonnegut). It is perfectly possible, perhaps even sensible, to read Billy Pilgrim’s entire Tralfamadorian experience as a fantastic, traumatic disorder brought about by his wartime experiences—as “not real.” Vonnegut leaves that question open, as a good writer should. That openness is the space in which the reader is allowed to make up his or her own mind.”

After Arundhaty read her passage there was further discussion on these matters. The book has all time travel and all that because he was disoriented, said KumKum. The war really damaged his brain, and that is the result shown in this book. There's no linear narration as a result. His mind is not stable. Once you understand that, the book makes sense as it goes, just as Geetha pointed out.

Initially, KumKum had trouble. She called Geetha and told her she had previously chosen a nice book by Divakaruni Banerjee – why did she change it? More than one reader had almost finished that book, The Last Queen by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni. Remember? As a result some readers read two books in place of one. Divakaruni, you could read in your sleep.

The book by Vonnegut was difficult to understand initially. But, Thomo said, once you understand that the purpose of this time travel, it takes care of two things. One is this guy Billy Pilgrim is not all there. For example in the passage Thomo was going to read he's attending to a patient, and he goes off to sleep …But then he goes into dreamland, which is his space travel. In the process, the author can knit together events in Billy Pilgrim's life. And then also discuss philosophical ideas, like the nature of time and death.

Every time there's a death, the author interjects the phrase, “So it goes.”

Vonnegut’s not a Christian, but he is okay with people deriving strength from religion.

Geetha confessed that the men were responsible for changing the novel. One disapproved of the first choice, and the other provided an acceptable substitute.

As Thomo said, initially, it was difficult. But then it gets easier as you just understand his way of writing. You have to get into the author’s head. These type of books, we should read in the group, or we’ll never muster courage to finish it, or the wisdom to decipher it. When it was published, it shot to the top of the New York Times bestseller list, said Thomo.

Perhaps, because that was a time when all these effects of the war were happening on TV in front on the eyes of Americans. The public was upset with all the wars that were happening. This was the time of Woodstock also. A lot of that Woodstock generation could identify with the book’s message of war destroying people’s minds. Vonnegut became a counterculture hero.

Thomo was born soon after World War II finished and never saw any war except the Bangladesh war, which was actually a walkover for the Indian army by the time the war actually started.

Someone suggested going to see late cartoonist Abu Abraham’s works on show at the Durbar Hall until April 21.

Thomo

The passage is about Billy Pilgrim going to sleep at the dentist’s chair. The time travel was in his imagination; that is what the author tries to convey, but in Billy’s mind it is real, that there are these aliens in a geodesic dome who are transporting him into different time zones.

Pamela said actually, the book is witty also. Pilgrim’s fiancée, Valencia Merble, was rich and ‘big as a house.’ We read in the novel:

“She was wearing trifocal lenses in harlequin frames, and the frames were trimmed with rhinestones. The glitter of the rhinestones was answered by the glitter of the diamond in her engagement ring. The diamond was insured for eighteen hundred dollars. Billy had found that diamond in Germany. It was booty of war.

Billy didn't want to marry ugly Valencia. She was one of the symptoms of his disease. He knew he was going crazy, when he heard himself proposing marriage to her, when he begged her to take the diamond ring and be his companion for life.”

Vonnegut’s description of very tragic situations is hilarious. It's really funny the way he puts it though the situation is a sad one.

Geetha

Geetha had originally chosen another passage but she then selected this passage bout Billy Pilgrim seeing a movie backwards and forwards about the war. She found it fascinating the way he's written the backwards flow of a movie because we see it on the screen and find it disconcerting when they take it backwards. He's put it down very descriptively and also you can also glean the philosophical ideas. It's very interesting to read.

Thomo was reminded of the film The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, how he changes back into a baby. The film stars Brad Pitt as a man who ages in reverse and Cate Blanchett as the love interest throughout his life.

“The American (bomber) fliers turned in their uniforms, became high school kids. And Hitler turned into a baby, Billy Pilgrim supposed. … Everybody turned into a baby, and all humanity, without exception, conspired biologically to produce two perfect people named Adam and Eve, he supposed.”

Geetha said it's his mind, fighting against the war, and taking him back to a normal, beautiful world, starting with Adam and Eve. You glimpse the writer's mind every now and again.

So it goes.

Joe

Joe (here wearing a bindi for Holi) read from a section where, as happens, in a war you take prisoners, and they're all arranged according to their official status, and the officers are treated differently than the enlisted men. Here we see some English officers and how they deal with the ordinary American soldiers.

It’s a comical interlude in which the English officers got rations from home for 500, instead of 50, and they had an excess of everything. They were living in luxury whereas the Americans are shown doing very poorly. They do all the dirty work also. Joe found the following couplet funny in a Cinderella play put on by the officers:

'Goodness me, the clock has struck-

Alackaday, and fuck my luck.'

Priya

In the passage Billy Pilgrim is in hospital in the POW camp. The name Pilgrim is taken from the The Pilgrim’s Progress, the spiritual journey of a Christian, said Priya. There is therefore lot about Christianity and what Vonnegut thinks about Jesus. ‘Christ-loving atheist’ is what Vonnegut calls himself. There are a lot of themes in the book and that may account for its popularity. He was also considered a counter-culture hero because he was presenting a different way to look at things, even religion. Valencia Merble, his oversize fiancée, not very comely, comes to meet him in the hospital.

Maharshi drawn by the Vonnegut's daughter

Later Priya shared a link where Vonnegut expounds on his view of Christianity to a fellow writer. In another article titled Yes, We Have No Nirvanas, in The Esquire, June 1, 1968, he takes apart Maharshi Mahesh Yogi. Vonnegut claimed Maharshi provides a service, but all he really had to sell was himself. Here is the opening of this long article:

“A Unitarian minister heard that I had been to see Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, guru to The Beatles and Donovan and Mia Farrow, and he asked me, "Is he a fake?" His name is Charley. Unitarians don't believe anything.

I am a Unitarian.

"No," I said. "It made me happy just to see him. His vibrations are lovely and profound. He teaches that man was not born to suffer and will not suffer if he practices Transcendental Meditation, which is easy as pie."

"I can't tell whether you're kidding or not."

"I better not be kidding, Charley."

"Why do you say that so grimly?"

"Because my wife and eighteen-year-old daughter are hooked. They've both been initiated. They meditate several times a day.

Nothing pisses them off anymore. They glow like bass drums with lights inside.”

Devika

Devika read the whole book. Parts of it, she thought, were interesting, but it took her a while to wrap her head around the whole novel.

But when she read this particular piece, a rather short one, she just burst out laughing, and chose it immediately. At that point, she was going through a rough patch, and this made her happy in the moment.

Billy Pilgrim comes out to take a leak and his trousers gets snagged in the barbed wire fence. He’s dancing to shake off the barbs, and a Russian POW, himself out for the same job, notices him, and goes to undo his hitches one by one, and releases him. Pilgrim goes off without a word. Geetha mentioned it's just like the Pakistanis and the Indians on the war front, each trying to get to know the other side. KumKum liked the piece.

Pamela

Pamela read the passage which ends with the guard reminding them to memorise their address in case they got lost in the town: Schlachthöf-funf, meaning Slaughter-house five. As the novelist writes:

“The slaughterhouse wasn't a busy place any more. Almost all the hooved animals in Germany had been killed and eaten and excreted by human beings, mostly soldiers. So it goes.”

That’s how the name of the book came about. Pamela likes the whole description where Billy Pilgrim as the star marches out in a light opera wearing a ridiculous costume. This whole thing is actually a kind of a mockery of the situation they were in.

These American POWs were going through so much but the author's made it sound very comical. He describes the city before it was bombed, and he says presciently that he knew that all the people standing around would soon be gone, and so also the people watching would be burnt alive. But before the event, they look like they're all very happy – confident of that particular moment, but none of them were going to survive.

It made Pamela think of her wedding day when she was so happy with all her uncles and aunts and cousins and everybody around her. Every year Pamela used to put on the video to enjoy watching it, but by the time she and John reached their fifteenth wedding anniversary, four-fifths of the guests in the video were no longer living. All those old relatives and friends were not there and they stopped watching the video after that. When we are happy and enjoying we don’t know how long it will last.

Kavita

Kavita took two different situations. One is where he is dreaming, and that brings out his habitual time travel in his imagination. In the passage a lady passes by who recognises three of the soldiers. She is matter of fact, and didn't consider them as real soldiers. One was too young, one too old, and Billy Pilgrim is there because he wants to keep warm. The real soldiers are all dead, she says.

Anyway, this is nothing about the space travel, though, since it is all in the slaughterhouse, it is part of the routine. The title is so deceptive, because when Kavita read it she thought it was going to be a very harrowing scene of a location, like the Nazi gas chambers, a concentration camp or something.

They stock up with spoons of malt syrup meant for pregnant ladies and Pilgrim even makes a lollipop out of syrup.

“He thrust it into his mouth.

A moment went by, and then every cell in Billy's body shook him with ravenous gratitude and applause.”

How ordinary are unforeseen pleasures of war!

A very funny thing takes place when Pilgrim and his wife sleep with each other on their honeymoon. He plants in her the seeds of a future Green Beret soldier. “In a tiny cavity in her great body she was assembling the materials for a Green Beret.” (Green Berets are a top special operations force of the US military, experts in unconventional warfare, counterterrorism, etc)

KumKum

KumKum said we understand the novel better when we go through it all together, having read it before by ourselves. Slaughterhouse-five by Kurt Vonnegut is a highly acclaimed novel that blends elements of science fiction, satire, and anti-war sentiment. Published in 1969, it's often considered Vonnegut's masterpiece and a classic of American literature.

At its core, Slaughterhouse-five is a satirical and anti-war novel that explores the experiences of its protagonist, Billy Pilgrim, during and after World War II. The narrative is unique in its structure, composed of science fiction, autobiography, and metafiction. It centres on Billy's experiences as an American soldier, his time as a prisoner of war in Germany, and his life after the war, including his abduction by aliens known as Tralfamadorians.

One of the most significant aspects of the novel is its treatment of time. Vonnegut employs a non-linear narrative style, with Billy experiencing moments of his life out of sequence, reflecting the Tralfamadorian concept of viewing all moments of time simultaneously. This approach allows Vonnegut to explore themes of fate, free will, and the human experience of facing war and its trauma.

Through its dark humour and poignant storytelling, Slaughterhouse-five offers a powerful commentary on the absurdity and destructiveness of war, as well as the resilience of the human spirit. It has been celebrated for its innovative story-telling, its powerful anti-war message, and its lasting impact on literature and popular culture.

KumKum chose to read from Chapter 8 of the novel. Howard W. Campbell, Jr., the American Nazi recruiter addresses the weary, malnourished American prisoners at the Slaughterhouse. He solicits them to join his Free American Corps to fight on the Russian front, promising food and freedom after the war is over. Edgar Derby, an ordinary soldier, stands up and in his courageous voice challenges Campbell, calling him a snake, worse than a snake, a blood-filled tick. “Derby spoke movingly of the American form of Government, with freedom and justice and opportunities and fair play for all. He said there wasn't a man there who wouldn't gladly die for those ideals.”

Just at that time an air-raid siren concludes the confrontation, and everyone takes shelter in a meat locker carved into the bedrock beneath the slaughterhouse. That alarm was a false one. The actual destruction of Dresden took place on the following day. So it goes.

KumKum’s passage had such a good ending. There is talk of “the brotherhood between the American and the Russian people, and how those two nations were going to crush the disease of Nazism, …”

Dresden was destroyed only a little while thereafter. Did the prisoners finally redeem themselves, asked Geetha?

We should read the book a second time to better understand it. We’ll be able to relate to everything that is being said. We have everyone else's perspective also. Most books – only when we read it twice – do we actually comprehend it, and we retain so much more. Discussions among readers like this, when we get together are invaluable. We miss Saras – she was overwhelmed with visitors it seems. Always a perceptive reader, she would have thrown more light. We missed her.

Pamela brought to notice a little paragraph on page 80, quite hilarious. Billy Pilgrim was lying at an angle on the corner brace, self-crucified. Holding himself there with a blue and ivory cloth, looped over the sill of the ventilator.

“Billy coughed when the door was opened, and when he coughed he shit thin gruel. [Isn't ‘shat’ the past participle of the verb shit?] This was in accordance with the Third Law of Motion according to Sir Isaac Newton. This law tells us that for every action there is a reaction which is equal and opposite in direction. This can be useful in rocketry.”

So hilarious!

After a few days of struggling, KumKum got into the swing of the novel, and found it filled with bits of ironic humour.

Joe said it's strange that this novel is considered satire and anti-war at the same time, because the actual crime of the Dresden firebombing, was a crime against humanity. It was the bombing a city mostly composed of civilians. It was a razing to the ground of city which had no military importance whatever. It was meant to terrorise civilians. And this, by the way, was not the largest firebombing of the Second World War.

The firebombing of Tokyo, which took place in March of 1945, had more casualties than the atomic bomb over Nagasaki. One million people were made homeless. About 100,000 civilians were killed by burning with incendiary explosives. And about 250,000 dwellings were razed to the ground. Perhaps 20 or 30 square miles of Tokyo were completely flattened.

It's only the victors in war who deal out justice and hold war tribunals like Nuremberg. But the defeated too had many war crimes committed against them which went unpunished. The atomic bomb would only have been the most barbaric.

The firebombing of Tokyo and the Dresden firebombing, were crimes that should have been prosecuted, and actually merited prosecution by a neutral body because they satisfy all the criteria of being against the rules of war. The bombing was aimed at civilians, it killed civilians, and it was not military targets that were targeted.

The atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was entirely unnecessary. It was a demonstration of brute force. The Japanese had already sued for peace and only the terms of surrender were to be worked out – the Japanese insisting only that their emperor should be spared.

Hiroshima after the atom bomb was dropped on August 6, 1945

America was doing this magical thing and wanted to show how powerful a weapon it possessed. But the Japanese were already defeated.

The Readings

Arundhaty p.12-15

I met his nice wife, Mary, to whom I dedicate this book. I dedicate it to Gerhard Müller, the Dresden taxi driver, too. Mary O'Hare is a trained nurse, which is a lovely thing for a woman to be.

Mary admired the two little girls I'd brought, mixed them in with her own children, sent them all upstairs to play games and watch television. It was only after the children were gone that I sensed that Mary didn't like me or didn't like something about the night.

She was polite but chilly.

'It's a nice cozy house you have here,' I said, and it really was.

‘I’ve fixed up a place where you can talk and not be bothered,' she said.

'Good,' I said, and I imagined two leather chairs near a fire in a paneled room, where two old soldiers could drink and talk. But she took us into the kitchen. She had put two straight-backed chairs at a kitchen table with a white porcelain top. That table top was screaming with reflected light from a two-hundred-watt bulb overhead. Mary had prepared an operating room. She put only one glass on it, which was for me. She explained that O'Hare couldn't drink the hard stuff since the war.

So we sat down. O'Hare was embarrassed, but he wouldn't tell me what was wrong. I couldn't imagine what it was about me that could bum up Mary so. I was a family man.

I'd been married only once. I wasn't a drunk. I hadn't done her husband any dirt in the war.

She fixed herself a Coca-Cola, made a lot of noise banging the ice-cube tray in the stainless steel sink. Then she went into another part of the house. But she wouldn't sit still. She was moving all over the house, opening and shutting doors, even moving furniture around to work off anger.

I asked O'Hare what I'd said or done to make her act that way.

'It's all right,' he said. "Don't worry about it. It doesn't have anything to do with you.'

That was kind of him. He was lying. It had everything to do with me.

So we tried to ignore Mary and remember the war. I took a couple of belts of the booze I'd brought. We would chuckle or grin sometimes, as though war stories were coming back, but neither one of us could remember anything good. O'Hare remembered one guy who got into a lot of wine in Dresden, before it was bombed, and we had to take him home in a wheelbarrow.

It wasn't much to write a book about. I remembered two Russian soldiers who had looted a clock factory. They had a horse-drawn wagon full of clocks. They were happy and drunk. They were smoking huge cigarettes they had rolled in newspaper.

That was about it for memories, and Mary was still making noise. She finally came out in the kitchen again for another Coke. She took another tray of ice cubes from the refrigerator, banged it in the sink, even though there was already plenty of ice out.

Then she turned to me, let me see how angry she was, and that the anger was for me.

She had been talking to herself, so what she said was a fragment of a much larger conversation. "You were just babies then!' she said.

'What?" I said.

'You were just babies in the war-like the ones upstairs! '

I nodded that this was true. We had been foolish virgins in the war, right at the end of childhood.

'But you're not going to write it that way, are you.' This wasn't a question. It was an accusation.

'I-I don't know,' I said.

'Well, I know,' she said. 'You'll pretend you were men instead of babies, and you'll be played in the movies by Frank Sinatra and John Wayne or some of those other glamorous, war-loving, dirty old men. And war will look just wonderful, so we'll have a lot more of them. And they'll be fought by babies like the babies upstairs.’

So then I understood. It was war that made her so angry. She didn't want her babies or anybody else's babies killed in wars. And she thought wars were partly encouraged by books and movies.

So I held up my right hand and I made her a promise 'Mary,' I said, 'I don't think this book is ever going to be finished. I must have written five thousand pages by now, and thrown them all away. If I ever do finish it, though, I give you my word of honor: there won't be a part for Frank Sinatra or John Wayne.

'I tell you what,' I said, 'I'll call it The Children's Crusade.'

She was my friend after that. (800 words)

Thomo Ch 3, p. 56-58

Billy traveled in time, opened his eyes, found himself staring into the glass eyes of a jade green mechanical owl. The owl was hanging upside down from a rod of stainless steel. The owl was Billy's optometer in his office in Ilium. An optometer is an instrument for measuring refractive errors in eyes-in order that corrective lenses may be prescribed.

Billy had fallen asleep while examining a female patient who was in a chair on the other side of the owl. He had fallen asleep at work before. It had been funny at first. Now Billy was starting to get worried about it, about his mind in general. He tried to remember how old he was, couldn't. He tried to remember what year it was. He couldn't remember that, either.

'Doctor,' said the patient tentatively.

Hm?' he said.

'You're so quiet.'

'Sorry.'

'You were talking away there-and then you got so quiet'

'Um.'

'You see something terrible?' 'Terrible?'

'Some disease in my eyes?'

'No, no,' said Billy, wanting to doze again. 'Your eyes are fine. You just need glasses for reading.' He told her to go across the corridor-to see the wide selection of frames there.

When she was gone, Billy opened the drapes and was no wiser as to what was outside.

The view was still blocked by a venetian blind., which he hoisted clatteringly. Bright sunlight came crashing in. There were thousands of parked automobiles out there, twinkling on a vast lake of blacktop. Billy's office was part of a suburban shopping center.

Right outside the window was Billy's own Cadillac El Dorado Coupe de Ville. He read the stickers on the bumper. 'Visit Ausable Chasm,' said one. 'Support Your Police Department,' said another. There was a third. 'Impeach Earl Warren' it said. The stickers about the police and Earl Warren were gifts from Billy's father-in-law, a member of the John Birch Society. The date on the license plate was 1967, which would make Billy Pilgrim forty-four years old. He asked himself this: 'Where have all the years gone?'

Billy turned his attention to his desk. There was an open copy of The Review of Optometry there. It was opened to an editorial, which Billy now read, his lips moving slightly.

What happens in 1968 will rule the fare of European optometrists for at least 50 years! Billy read. With this warning, Jean Thiriart, Secretary of the National Union of Belgium Opticians, is pressing for formation of a 'European Optometry Society.' The alternatives, he says, will be the obtaining of Professional status, or, by 1971, reduction to the role of spectacle-sellers.

Billy Pilgrim tried hard to care.

A siren went off, scared the hell out of him. He was expecting the Third World War at any time. The siren was simply announcing high noon. It was housed in a cupola atop a firehouse across the street from Billy's office.

Billy closed his eyes. When he opened them, he was back in the Second World War again. His head was on the wounded rabbi's shoulder. A German was kicking his feet, telling him to wake up, that it was time to move on. (524 words)

Geetha Ch 4, p. 73-75 Billy sees a movie about American bombers in the II World War, backwards

Billy Pilgrim padded downstairs on his blue and ivory feet. He went into the kitchen, where the moonlight called his attention to a half bottle of champagne on the kitchen table, all that was left from the reception in the tent. Somebody had stoppered it again.

Drink me,' it seemed to say.

So Billy uncorked it with his thumbs. It didn't make a pop. The champagne was dead.

So it goes.

Billy looked at the clock on the gas stove. He had an hour to kill before the saucer came. He went into the living room, swinging the bottle like a dinner bell, turned on the television. He came slightly unstuck in time, saw the late movie backwards, then forwards again. It was a movie about American bombers in the Second World War and the gallant men who flew them. Seen backwards by Billy, the story went like this: American planes, full of holes and wounded men and corpses took off backwards from an airfield in England. Over France a few German fighter planes flew at them backwards, sucked bullets and shell fragments from some of the planes and crewmen. They did the same for wrecked American bombers on the ground, and those planes flew up backwards to join the formation.

The formation flew backwards over a German city that was in flames. The bombers opened their bomb bay doors, exerted a miraculous magnetism which shrunk the fires, gathered them into cylindrical steel containers, and lifted the containers into the bellies of the planes. The containers were stored neatly in racks. The Germans below had miraculous devices of their own, which were long steel tubes. They used them to suck more fragments from the crewmen and planes. But there were still a few wounded Americans, though, and some of the bombers were in bad repair. Over France, though, German fighters came up again, made everything and everybody as good as new.

When the bombers got back to their base, the steel cylinders were taken from the racks and shipped back to the United States of America, where factories were operating night and day, dismantling the cylinders, separating the dangerous contents into minerals.

Touchingly, it was mainly women who did this work. The minerals were then shipped to specialists in remote areas. It was their business to put them into the ground., to hide them cleverly, so they would never hurt anybody ever again.

The American fliers turned in their uniforms, became high school kids. And Hitler turned into a baby, Billy Pilgrim supposed. That wasn't in the movie. Billy was extrapolating. Everybody turned into a baby, and all humanity, without exception, conspired biologically to produce two perfect people named Adam and Eve, he supposed. (454 words)

Saras Ch 4 & 5 p. 85-88

And then Billy was a middle-aged optometrist again, playing hacker's golf this time-on a blazing summer Sunday morning. Billy never went to church any more. He was hacking with three other optometrists. Billy was on the green in seven strokes, and it was his turn to putt.

It was an eight-foot putt and he made it. He bent over to take the ball out of the cup, and the sun went behind a cloud. Billy was momentarily dizzy. When he recovered, he wasn't on the golf course any more. He was strapped to a yellow contour chair in a white chamber aboard a flying saucer, which was bound for Tralfamadore.

'Where am I?' said Billy Pilgrim.

'Trapped in another blob of amber, Mr. Pilgrim. We are where we have to be just now-three hundred million miles from Earth, bound for a time warp which will get us to Tralfamadore in hours rather than centuries.'

'How-how did I get here?

It would take another Earthling to explain it to you. Earthlings are the great explainers, explaining why this event is structured as it is, telling how other events may be achieved or avoided. I am a Tralfamadorian, seeing all time as you might see a stretch of Rocky Mountains. All time is all time. It does not change. It does not lend itself to warnings or explanations. It simply is. Take it moment by moment, and you will find that we are all, as I've said before, bugs in amber.'

'You sound to me as though you don't believe in free will,' said Billy Pilgrim.

'If I hadn't spent so much time studying Earthlings,' said the Tralfamadorian, 'I wouldn't have any idea what was meant by "free will." I've visited thirty-one inhabited planets in the universe, and I have studied reports on one hundred more. Only on Earth is there any talk of free will.

Ch 5

Billy Pilgrim says that the Universe does not look like a lot of bright little dots to the creatures from Tralfamadore. The creatures can see where each star has been and where it is going, so that the heavens are filled with rarefied, luminous spaghetti. And Tralfamadorians don't see human beings as two-legged creatures, either. They see them as great millipedes with babies' legs at one end and old people's legs at the other,' says Billy Pilgrim.

Billy asked for something to read on the trip to Tralfamadore. His captors had five million Earthling books on microfilm, but no way to project them in Billy's cabin. They had only one actual book in English, which would be placed in a Tralfamadorian museum. It was Valley of the Dolls, by Jacqueline Susann.

Billy couldn't read Tralfamadorian, of course, but he could at least see how the books were laid out-in brief clumps of symbols separated by stars. Billy commented that the clumps might be telegrams.

'Exactly,' said the voice.

'They are telegrams?'

'There are no telegrams on Tralfamadore. But you're right: each clump of-symbols is a brief, urgent message describing a situation, a scene, We Tralfamadorians read them all at once, not one after the other. There isn't any particular relationship between all the messages, except that the author has chosen them carefully, so that, when seen all at once, they produce an image of life that “is beautiful and surprising and deep. There is no beginning, no middle, no end, no suspense, no moral, no causes, no effects. What we love in our books are the depths of many marvelous moments seen all at one time. (592 words)

Joe Ch 5 p.96-98 The English officers who are well-supplied entertain the American enlisted men in prison

At each place was a safety razor, a washcloth, a package of razor blades, a chocolate bar, two cigars, a bar of soap,, ten cigarettes, a book of matches, a pencil and a candle.

Only the candles and the soap were of German origin. They had a ghostly, opalescent similarity. The British had no way of knowing it, but the candles and the soap were made from the fat of rendered Jews and Gypsies and fairies and communists, and other enemies of the State.

So it goes.

The banquet hall was illuminated by candlelight. There were heaps of fresh baked white bread on the tables, gobs of butter, pots of marmalade. There were platters of sliced beef from cans. Soup and scrambled eggs and hot marmalade pie were yet to come.

And, at the far end of the shed, Billy saw pink arches with azure draperies hanging between them, and an enormous clock, and two golden thrones, and a bucket and a ]mop.

It was in this setting that the evening's entertainment would take place, a musical version of Cinderella, the most popular story ever told.

Billy Pilgrim was on fire, having stood too close to the glowing stove. The hem of his little coat was burning. It was a quiet, patient sort of fire-like the burning of punk.

Billy wondered ff there was a telephone somewhere. He wanted to call his mother, to tell her he was alive and well.

There was silence now, as the Englishmen looked in astonishment at the frowsy creatures they had so lustily waltzed inside. One of the Englishmen saw that Billy was on fire. 'You're on fire lad!' he said, and he got Billy away from the stove and beat out the sparks with his hands.

When Billy made no comment on this, the Englishman asked him, 'Can you talk? Can you hear?'

Billy nodded.

The Englishman touched him exploratorily here and there, filled with pity. 'My God-what have they done to you, lad? This isn't a man. It's a broken kite.'

'Are you really an American?' said the Englishman.

'Yes,' said Billy.

And your rank?'

'Private.'

'What became of your boots, lad?'

'I don't remember.'

'Is that coat a joke?'

'Sir?'

'Where did you get such a thing?'

Billy had to think hard about that. 'They gave it to me,' he said at last.

'Jerry gave it to you?'

'Who? '

'The Germans gave it to you?'

'Yes.'

Billy didn't like the questions. They were fatiguing.

'Ohhhh-Yank, Yank, Yank,' said the Englishman, 'that coat was an insult,

'Sir?

It was a deliberate attempt to humiliate you. You mustn't let Jerry do things like that.'

Billy Pilgrim swooned.

Billy came to on a chair facing the stage. He had somehow eaten, and now he was watching Cinderella. Some part of him had evidently been enjoying the performance for quite a while. Billy was laughing hard.

The women in the play were really men, of course. The clock had just struck midnight and Cinderella was lamenting

'Goodness me, the clock has struck-

Alackaday, and fuck my luck.'

Billy found the couplet so comical that he not only laughed-he shrieked. He went on shrieking until he was carried out of the shed and into another, where the hospital was. It was a six-bed hospital. There weren't any other patients in there. (556 words)

Priya Ch 5, p.108-110

She asked him if there was anything she could bring him from the outside, and he said,

'No. I have just about everything I want.'

'What about books?' said Valencia.

'I'm right next to one of the biggest private libraries in the world,' said Billy, meaning Eliot Rosewater's collection of science fiction.

Rosewater was on the next bed, reading, and Billy drew him into the conversation, asked him what he was reading this time.

So Rosewater told him. It was The Gospel from Outer Space, by Kilgore Trout. It was about a visitor from outer space, shaped very much like a Tralfamadorian by the way.

The visitor from outer space made a serious study of Christianity, to learn, if he could, why Christians found it so easy to be cruel. He concluded that at least part of the trouble was slipshod storytelling in the New Testament. He supposed that the intent of the Gospels was to teach people, among other things, to be merciful, even to the lowest of the low.

But the Gospels actually taught this:

Before you kill somebody, make absolutely sure he isn't well connected. So it goes.

The flaw in the Christ stories, said the visitor from outer space, was that Christ, who didn't look like much, was actually the Son of the Most Powerful Being in the Universe.

Readers understood that, so, when they came to the crucifixion, they naturally thought, and Rosewater read out loud again:

Oh, boy-they sure picked the wrong guy to lynch that time!

And that thought had a brother: 'There are right people to lynch.' Who? People not well connected. So it goes.

The visitor from outer space made a gift to Earth of a new Gospel. In it, Jesus really was a nobody, and a pain in the neck to a lot of people with better connections than he had. He still got to say all the lovely and puzzling things he said in the other Gospels.

So the people amused themselves one day by nailing him to a cross and planting the cross in the ground. There couldn't possibly be any repercussions, the lynchers thought.

The reader would have to think that, too, since the new Gospel hammered home again and again what a nobody Jesus was.

And then, just before the nobody died, the heavens opened up, and there was thunder and lightning. The voice of God came crashing down. He told the people that he was adopting the bum as his son giving him the full powers and privileges of The Son of the Creator of the Universe throughout all eternity. God said this From this moment on, He will punish horribly anybody who torments a bum who has no connections!

Devika Ch 5 p.123-124

The candle in the hospital had gone out. Poor old Edgar Derby had fallen asleep on the cot next to Billy's. Billy was out of bed, groping along a wall, trying to find a way out because he had to take a leak so badly.

He suddenly found a door, which opened, let him reel out into the prison night. Billy was loony with time-travel and morphine. He delivered himself to a barbed-wire fence which snagged him in a dozen places. Billy tried to back away from it but the barbs wouldn't let go. So Billy did a silly little dance with the fence, taking a step this way, then that way, then returning to the beginning again.

A Russian, himself out in the night to take a leak, saw Billy dancing-from the other side of the fence. He came over to the curious scarecrow, tried to talk with it gently, asked it what country it was from. The scarecrow paid no attention, went on dancing. So the Russian undid the snags one by one, and the scarecrow danced off into the night again without a word of thanks.

The Russian waved to him, and called after him in Russian, 'Good-bye.'

Pamela Ch 6 p.150-153

So out of the gate of the railroad yard and into the streets of Dresden marched the light opera. Billy Pilgrim was the star. He led the parade. Thousands of people were on the sidewalks, going home from work. They were watery and putty-colored, having eaten mostly potatoes during the past two years. They had expected no blessings beyond the mildness of the day. Suddenly-here was fun.

Billy did not meet many of the eyes that found him so entertaining. He was enchanted by the architecture of the city. Merry amoretti wove garlands above windows. Roguish fauns and naked nymphs peeked down at Billy from festooned cornices. Stone monkeys frisked among scrolls and seashells and bamboo.

Billy, with his memories of the future, knew that the city would be smashed to smithereens and then burned-in about thirty more days. He knew, too, that most of the people watching him would soon be dead. So it goes.

And Billy worked his hands in his muff as he marched. His fingertips, working there in the hot darkness of the muff, wanted to know what the two lumps in the lining of the little impresario's coat were. The fingertips got inside the lining. They palpated the lumps, the pea-shaped thing and the horseshoe-shaped thing. The parade had to halt by a busy corner. The traffic light was red.

There at the corner, in the front rank of pedestrians, was a surgeon who had been operating all day. He was a civilian, but his posture was military. He had served in two world wars. The sight of Billy offended him, especially after he learned from the guards that Billy was an American. It seemed to him that Billy was in abominable taste, supposed that Billy had gone to a lot of silly trouble to costume himself just so.

The surgeon spoke English, and he said to Billy, 'I take it you find war a very comical thing.'

Billy looked at him vaguely. Billy had lost track momentarily of where he was or how he had gotten there. He had no idea that people thought he was clowning. It was Fate, of course, which had costumed him-Fate, and a feeble will to survive.

'Did you expect us to laugh? ' the surgeon asked him.

The surgeon was demanding some sort of satisfaction. Billy was mystified. Billy wanted to be friendly, to help, if he could, but his resources were meager. His fingers now held the two objects from the lining of the coat. Billy decided to show the surgeon what they were.

'You thought we would enjoy being mocked? ' the surgeon said. 'And do you feel proud to represent America as you do?' Billy withdrew a hand from his muff, held it under the surgeon's nose. On his palm rested a two-carat diamond and a partial denture. The denture was an obscene little artifact-silver and pearl and tangerine. Billy smiled.

The parade pranced, staggered and reeled to the gate of the Dresden slaughterhouse, and then it went inside. The slaughterhouse wasn't a busy place any more. Almost all the hooved animals in Germany had been killed and eaten and excreted by human beings, mostly soldiers. So it goes.

The Americans were taken to the fifth building inside the gate. It was a one-story cement-block cube with sliding doors in front and back. It had been built as a shelter for pigs about to be butchered. Now it was going to serve as a home away from home for one hundred American prisoners of war. There were bunks in there, and two potbellied stoves and a water tap. Behind it was a latrine, which was a one-rail fence with buckets under it.

There was a big number over the door of the building. The number was five. Before the Americans could go inside, their only English-speaking guard told them to memorize their simple address, in case they got lost in the big city. Their address was this: Schlachthöf-funf.' Schlachthöf meant slaughterhouse. Funf was good old five. (671 words)

Kavita p. 159-161

When the three fools found the communal kitchen, whose main job was to make lunch for workers in the slaughterhouse, everybody had gone home but one woman who had been waiting for them impatiently. She was a war widow. So it goes. She had her hat and coat on. She wanted to go home, too, even though there wasn't anybody there. Her white gloves were laid out side by side on the zinc counter top.

She had two big cans of soup for the Americans. It was simmering over low fires on the gas range.

She had stacks of loaves of black bread, too.

She asked Gluck if he wasn't awfully young to be in the army. He admitted that he was.

She asked Edgar Derby if he wasn't awfully old to be in the army. He said he was.

She asked Billy Pilgrim what he was supposed to be. Billy said he didn't know. He was just trying to keep warm.

'All the real soldiers are dead,' she said. It was true. So it goes.

Another true thing that Billy saw while he was unconscious in Vermont was the work that he and the others had to do in Dresden during the month before the city was destroyed. They washed windows and swept floors and cleaned lavatories and put jars into boxes and sealed cardboard boxes in a factory that made malt syrup. The syrup was enriched with vitamins and minerals. The syrup was for pregnant women.

The syrup tasted like thin honey laced with hickory smoke, and everybody who worked in the factory secretly spooned it all day long. They weren't pregnant, but they needed vitamins and minerals, too. Billy didn't spoon syrup on his first day at work, but lots of other Americans did.

Billy spooned it on his second day. There were spoons hidden all over the factory, on rafters, in drawers, behind radiators, and so on. They had been hidden in haste by persons who had been spooning syrup, who had heard somebody else coming. Spooning was a crime.

On his second day, Billy was cleaning behind a radiator and he found a spoon. To his back was a vat of syrup that was cooling. The only other person who could see Billy and his spoon was poor old Edgar Derby, who was washing a window outside. The spoon was a tablespoon. Billy thrust it into the vat, turned it around and around, making a gooey lollipop. He thrust it into his mouth.

A moment went by, and then every cell in Billy's body shook him with ravenous gratitude and applause.

There were diffident raps at the factory window. Derby was out there, having seen all.

He wanted some syrup, too.

So Billy made a lollipop for him. He opened the window. He stuck the lollipop into poor old Derby's gaping mouth. A moment passed, and then Derby burst into tears. Billy closed the window and hid the sticky spoon. Somebody was coming. (498 words)

KumKum Ch 8 p.162-164

The Americans in the slaughterhouse had a very interesting visitor two days before Dresden was destroyed. He was Howard W. Campbell, Jr., an American who had become a Nazi. Campbell was the one who had written the monograph about the shabby behavior of American prisoners of war. He wasn't doing more research about prisoners now. He had come to the slaughterhouse to recruit men for a German military unit called 'The Free American Corps.' Campbell was the inventor and commander of the unit, which was supposed to fight only on the Russian front.

Campbell was an ordinary looking man, but he was extravagantly costumed in a uniform of his own design. He wore a white ten-gallon hat and black cowboy boots decorated with swastikas and stars. He was sheathed in a blue body stocking which had yellow stripes running from his armpits to his ankles. His shoulder patch was a silhouette of Abraham Lincoln's profile on a field of pale green. He had a broad armband which was red, with a blue swastika in a circle of white.

He was explaining this armband now in the cement-block hog barn.

Billy Pilgrim had a boiling case of heartburn, since he had been spooning malt syrup all day long at work. The heartburn brought tears to his eves, so that his image of Campbell was distorted by jiggling lenses of salt water.

'Blue is for the American sky,' Campbell was saying. 'White is for the race that pioneered the continent, drained the swamps and cleared the forests and built the roads and bridges. Red is for the blood of American patriots which was shed so gladly in years gone by.'

Campbell's audience was sleepy. It had worked hard at the syrup factory, and then it had marched a long way home in the cold. It was skinny and hollow-eyed. Its skins were beginning to blossom with small sores. So were its mouths and throats and intestines. The malt syrup it spooned at the factory contained only a few of the vitamins and minerals every Earthling needs.

Campbell offered the Americans food now, steaks and mashed potatoes and gravy and mince pie, if they would join the Free Corps. 'Once the Russians are defeated,' he went on, you will be repatriated through Switzerland.'

There was no response.

'You're going to have to fight the Communists sooner or later,' said Campbell. "Why not get it over with now?'

And then it developed that Campbell was not going to go unanswered after all. Poor old Derby, the doomed high school teacher, lumbered to his feet for what was probably the finest moment in his life. 'Mere are almost no characters in this story, and almost no dramatic confrontations, because most of the people in it are so sick and so much the listless playthings of enormous forces. One of the main effects of war, after an, is that people are discouraged from being characters. But old Derby was a character now.

His stance was that of a punch-drunk fighter. His head was down, his fists were out front, waiting for information and battle plan. Derby raised his head, called Campbell a snake. He corrected that. He said that snakes couldn't help being snakes, and that Campbell, who could help being what he was, was something much lower than a snake or a rat-or even a blood-filled tick.

Campbell smiled.

Derby spoke movingly of the American form of government, with freedom and justice and opportunities and fair play for all. He said there wasn't a man there who wouldn't gladly die for those ideals.

He spoke of the brotherhood between the American and the Russian people, and how those two nations were going to crush the disease of Nazism, which wanted to infect the whole world.

The air-raid sirens of Dresden howled mournfully. (637 words)

No comments:

Post a Comment