Devika – Chapter 7: A dog follows Zott from the grocery and is made their pet, Six-Thirty

Many people go to breeders to find a dog, and others to the pound, but sometimes, especially when it's really meant to be, the right dog finds you.

It was a Saturday evening, about a month later, and Elizabeth had run down to the local deli to get something for dinner. As she left the store, her arms laden with a large salami and a bag of groceries, a mangy, smelly dog, hidden in the shadows of the alley, watched her walk by. Although the dog hadn't moved in five hours, he took one look at her, pulled himself up, and followed.

Calvin happened to be at the window when he saw Elizabeth strolling toward the house, a dog following a respectful five paces behind, and as he watched her walk, a strange shudder swept through his body. "Elizabeth Zott, you're going to change the world," he heard himself say. And the moment he said it, he knew it was true.

She was going to do something so revolutionary, so necessary, that her name despite a never-ending legion of naysayers-would be immortalized. And as if to prove that point, today she had her first follower.

"Who's your friend?" he called out to her, shaking off the odd feeling.

"It's six thirty," she called back after glancing at her wrist.

Six-Thirty was badly in need of a bath. Tall, gray, thin, and covered with barbed-wire-like fur that made him look as if he'd barely survived electrocution, he stood very still as they shampooed him, his gaze fixed on Elizabeth.

"I guess we should try to find his owner," Elizabeth said reluctantly. "I'm sure someone is worried to death."

"This dog doesn't have an owner," Calvin assured her, and he was right. Later calls to the pound and listings in the newspaper's lost and found column turned up nothing. But even if it had, Six-Thirty had already made his intentions clear: to stay.

In fact, "stay" was the first word he learned, although within weeks, he also learned at least five others. That was what surprised Elizabeth most-Six-Thirty's ability to learn.

“Do you think he’s unusual?” She asked Calvin more than once. He seems to pick things up so quickly.”

“He’s grateful,” Calvin said. “He wants to please us.”

But Elizabeth was right: Six-Thirty had been trained to pick things up quickly.

Bombs, specifically.

Before he'd ended up in that alley, he'd been a canine bomb-sniffer trainee at Camp Pendleton, the local marine base. Unfortunately, he'd failed miserably. Not only could he never seem to sniff out the bomb in time, but he also had to endure the praise heaped upon the smug German shepherds who always did. He was eventually discharged — not honorably— by his angry handler, who drove him out to the highway and dumped him in the middle of nowhere. Two weeks later he found his way to that alley. Two weeks and five hours later, he was being shampooed by Elizabeth and she was calling him Six-Thirty.

Priya – Ch 13: Zott gets fired By Donatti, the department head, for being pregnant and unwed. She disputes.

"I'm afraid you've put us in a terrible, terrible position, Miss Zott," scolded Dr. Donatti a week later as he pushed a termination notice across the table in her direction.

"You're firing me?" Elizabeth said, confused.

"I'd like to get through this as civilly as possible."

"Why am I being fired? On what grounds?"

"I think you know."

"Enlighten me," she said, leaning forward, her hands clasped together in a tight mass, her number-two pencil behind her left ear glinting in the light. She wasn't sure from where her composure came, but she knew she must keep it.

He glanced at Miss Frask, who was busy taking notes.

"You're with child," Donatti said. "Don't try and deny it."

"Yes, I'm pregnant. That is correct."

"That is correct?" he choked. "That is correct?"

"Again. Correct. I am pregnant. What does that have to do with my work?"

"Please!"

"I'm not contagious," she said, unfolding her hands. "I do not have cholera. No one will catch having a baby from me."

"You have a lot of nerve," Donatti said. "You know very well women do not continue to work when pregnant. But you—you're not only with child, you're unwed.

It's disgraceful."

"Pregnancy is a normal condition. It is not disgraceful. It is how every human being starts."

"How dare you," he said, his voice rising. "A woman telling me what pregnancy is. Who do you think you are?"

She seemed surprised by the question. "A woman," she said

"Miss Zott," Miss Frask stated, "our code of conduct does not allow for this sort of thing and you know it. You need to sign this paper, and then you need to clean out your desk. We have standards."

But Elizabeth didn't flinch. "I'm confused," she said. "You're firing me on the basis of being pregnant and unwed. What about the man?"

"What man? You mean Evans?" Donatti asked.

"Any man. When a woman gets pregnant outside of marriage, does the man who made her pregnant get fired, too?"

"What? What are you talking about?"

"Would you have fired Calvin, for instance?"

"Of course not!"

"If not, then, technically, you have no grounds to fire me."

Donatti looked confused. What? "Of course, I do," he stumbled. "Of course, I do! You're the woman! You're the one who got knocked up!"

"That's generally how it works. But you do realize that a pregnancy requires a man's sperm."

"Miss Zott, I'm warning you. Watch your language."

"You're saying that if an unmarried man makes an unmarried woman pregnant, there is no consequence for him. His life goes on. Business as usual."

"This is not our fault," Frask interrupted. "You were trying to trap Evans into marriage. It's obvious."

"What I know," she said, pushing a stray hair away from her forehead, "is that Calvin and I did not want to have children. I also know that we took every precaution to ensure that outcome. This pregnancy is a failure of contraception, not morality. It's also none of your business."

"You've made it our business!" Donatti suddenly shouted. "And in case you weren't aware, there is a surefire way not to get pregnant and it starts with an "A'! We have rules, Miss Zott! Rules!"

"Not on this you don't," Elizabeth said calmly. "I've read the employee manual front to back."

"It's an unwritten rule!"

"And thus not legally binding."

Kavita – Ch 15: Zott visits the obstetrician Mason and confesses how much rowing she does on the erg machine

She looked away. She didn't really know him. Worse, she wasn't sure, despite his assurances, that her feelings were allowable. She'd come to believe she was the only woman on earth who'd planned to remain childless. "If I'm being perfectly honest," she finally said, her voice heavy with guilt, "I don't think I can do this. I was not planning on being a mother."

"Not every woman wants to be a mother," he agreed, surprising her. "More to the point, not every woman should be." He grimaced as if thinking of someone in particular. "Still, I'm surprised by how many women sign up for motherhood considering how difficult pregnancy can be morning sickness, stretch marks, death.

Again, you're fine," he added quickly, taking in her horrified face. "It's just that we tend to treat pregnancy as the most common condition in the world— as ordinary as stubbing a toe-when the truth is, it's like getting hit by a truck. Although obviously a truck causes less damage." He cleared his throat, then made a note in her file.

"What I mean to say is, the exercise is helping. Although I'm not sure how you erg properly at this stage. Pulling into the sternum would be problematic. What about The Jack LaLanne Show? Ever watch him?"

At the mention of Jack LaLanne's name, Elizabeth's face fell.

"Not a fan," he said. "No problem. Just the erg, then."

"I only kept on with it," she offered in a low voice, "because it exhausts me to the point where I can sometimes sleep. But also because I thought it might, well—"

"I understand," he said, cutting her off and looking both ways as if making sure no one else could hear. "Look, I'm not one of those people who believe a woman should have to—" He stopped abruptly. "Nor do I believe that—" He stopped again. "A single woman... a widow ... it's ... Never mind," he said as he reached for her file. "But the truth is, that erg probably made you stronger; made the baby stronger for that matter. More blood to the brain, better circulation. Have you noticed it has a calming effect on the baby? Probably all that back and forth."

She shrugged.

"How far are you erging?"

"Ten thousand meters."

"Every day?"

"Sometimes more."

Arundhaty – Ch 16: Zott has a baby girl and checks herself out to go home and feed Six-Thirty, their dog

“Library?” Elizabeth asked Six-Thirty about five weeks later. “I’ve got an appointment with Dr. Mason later today and I’d like to return these books first. I’m thinking you might enjoy Moby-Dick. It’s a story about how humans continually underestimate other life-forms. At their peril.”

In addition to the receptive learning technique, Elizabeth had been reading aloud to him, long ago replacing simple children’s books with far weightier texts. “Reading aloud promotes brain development,” she’d told him, quoting a research study she’d read. “It also speeds vocabulary accumulation.” It seemed to be working because, according to her notebook, he now knew 391 words.

“You’re a very smart dog,” she’d told him just yesterday, and he longed to agree, but the truth was, he still didn’t understand what “smart” meant. The word seemed to have as many definitions as there were species, and yet humans—with the exception of Elizabeth—seemed to only recognize “smart” if and when it played by their own rules. “Dolphins are smart,” they’d say. “But cows aren’t.” This seemed partly based on the fact that cows didn’t do tricks. In Six-Thirty’s view that made cows smarter, not dumber. But again, what did he know?

Three hundred ninety-one words, according to Elizabeth. But really, only 390. Worse, he’d just learned that English wasn’t the only human language. Elizabeth revealed that there were hundreds, maybe thousands of others, and that no human spoke them all. In fact, most people spoke only one—maybe two—unless they were something called Swiss and spoke eight. No wonder people didn’t understand animals. They could barely understand each other.

At least she realized he would not be able to draw. Drawing seemed to be the way young children preferred to communicate, and he admired their efforts even if their results fell short of the mark. Not a day went by when he didn’t witness little fingers earnestly pressing their chunky chalks into the sidewalk, their impossible houses and primitive stick figures filling the cement with a story no one understood but themselves.

“What a pretty picture!” he heard a mother say earlier that week as she looked down on her child’s ugly, violent scribble. Human parents, he’d noted, had a tendency to lie to their children.

“It’s a puppy,” her child said, her hands covered in chalk.

“And such a pretty puppy!” the mother rejoined. “No,” the child said, “it’s not pretty. The puppy’s dead. It got killed!” Which Six-Thirty, after a second, closer look, found disturbingly accurate.

“It is not a dead puppy,” the mother said sternly. “It is a very happy puppy, and it is eating a bowl of ice cream.” At which point the frustrated child flung the chalk across the grass and stomped off for the swings.

He retrieved it. A gift for the creature.

…

Thirteen hours later, Dr. Mason held the infant up for an exhausted Elizabeth to see.

…

I’ll swing by your room tomorrow. In the meantime, rest.”

But worried about Six-Thirty, Elizabeth checked herself out the very next morning.

…

“It’s a girl,” Elizabeth told him, smiling.

Hello, Creature! It’s me! Six-Thirty! I’ve been worried sick!

“I’m so sorry,” she said, unlocking the door. “You must be starving. It’s”—she consulted her watch—“nine twenty-two. You haven’t eaten in more than twenty-four hours.”

Six-Thirty wagged his tail in excitement. Just as some families give their children names starting with the same letter (Agatha, Alfred) and others prefer the rhyme (Molly, Polly) his family went by the clock. He was named Six-Thirty to commemorate the exact time they’d become a family. And now he knew what the creature would be called.

Hello, Nine Twenty-Two! he communicated. Welcome to life on the outside! How was the trip? Please, come in, come in! I’ve got chalk.

Shoba – Ch 17: Neighbour Harriet Sloane introduces herself to the pregnant and suffering Zott

"I'm a terrible mother," she said in a rush. "It's not just the way you found me asleep on the job, it's many things—or rather, everything."

"Be more specific."

"Well, for instance, Dr. Spock says I'm supposed to put her on a schedule, so I made one, but she won't follow it."

Harriet Sloane snorted

"And I'm not having any of those moments you're supposed to have— you know, the moments_"

"I don't"

"The blissful moments-"

"Women's magazine rot," Sloane interrupted. "You need to steer clear of that stuff. It's complete fiction."

"But the feelings I'm having—I I don't think they're normal. I never wanted to have children," she said, "and now I have one and I'm ashamed to say I've been ready to give her away at least twice now."

Mrs. Sloane stopped at the back door.

"Please," Elizabeth begged. "Don't think badly of me—"

"Wait," Sloane said, as if she'd misheard. "You've wanted to give her away ... twice?" Then she shook her head and laughed in a way that made Elizabeth shrink.

"It's not funny."

"Twice? Really? Twenty times would still make you an amateur."

Elizabeth looked away.

"Hells bells," huffed Mrs. Sloane sympathetically. "You're in the midst of the toughest job in the world. Did your mother never tell you?"

And at the mention of her mother, Sloane noticed the young woman's shoulders tense.

"Okay," she said in a softer tone. "Never mind. Just try not to worry so much. You're doing fine, Miss Zott. It'll get better."

“What if it doesn’t ?” Elizabeth said desperately. “What if .. what if it gets worse?”

“Although she wasn’t the type to touch people Mrs. Sloane found herself leaving the sanctuary of the door to press down lightly on the young woman's shoulders "It gets better,"' he said. "What’s your name, Miss Zott”

“Elizabeth.”

Mrs. Sloane lifted her hands. "Well, Elizabeth, I'm Harriet."

Thomo – Ch 18 Elizabeth Zott considers names for her daughter.

So, sometime after it was all over, when a nurse came in with a stack of papers demanding to know something how she felt? she decided to tell her.

"Mad?" the nurse had asked.

"Yes, mad," Elizabeth had answered. Because she was.

"Are you sure?" the nurse had asked.

"Of course I'm sure!"

And the nurse, who was tired of tending to women who were never at their best-

—this one had practically engraved her name on her arm during labor-

—wrote "Mad" on the

birth certificate and stalked out.

So there it was: the baby's legal name was Mad. Mad Zott.

Elizabeth only discovered the issue a few days later at home when she'd stumbled across the birth certificate in a jumble of hospital paperwork still lumped on the kitchen

table. "What's this?" she'd said, looking at the fancy calligraphed certificate in astonishment. "Mad Zott? For god's sake! Did I take off that much skin?" She immediately set about to rename the baby, but there was a problem. She'd originally believed the right name would present itself the moment she saw her daughter's face,

but it hadn't.

Now, standing in her laboratory, looking down at the small lump who lay sleeping in a large basket lined with blankets, she studied her child's features. "Suzanne?" she said cautiously. "Suzanne Zott?" But it didn't feel right. "Lisa? Lisa Zott? Zelda Zott?" Nothing. "Helen Zott?" she tried. "Fiona Zott. Marie Zott?" Still nothing. She placed her hands on her hips, as if bracing herself. "Mad Zott," she finally ventured.

The baby's eyes flew open.

From his station beneath the table, Six-Thirty exhaled. He'd spent enough time on a playground to understand one could not name a child just anything, especially when the baby's name had only come about from misunderstanding or, in Elizabeth's case, payback. In his opinion, names mattered more than the gender, more than tradition, more than whatever sounded nice. A name defined a person—or in his case, a dog. It was a personal flag one waved the rest of one's life; it had to be right. Like his name, which he'd had to wait more than a year to receive. Six-Thirty. Did it get any better than that?

"Mad Zott," he heard Elizabeth whisper. "Dear god."

Six-Thirty got up and padded off to the bedroom. Unbeknownst to Elizabeth, he'd been stashing biscuits under the bed for months, a practice he'd started just after Calvin died.

It wasn't because he feared Elizabeth might forget to feed him, but rather because he'd made his own important chemical discovery. When faced with a serious problem, he'd found it helped to eat.

Mad, he considered, chewing a biscuit. Madge. Mary. Monica. He withdrew another biscuit, crunching loudly. He was very fond of his biscuits—yet another triumph from the kitchens of Elizabeth Zott. It made him think, Why not name the baby after something in the kitchen? Pot. Pot Zott. Or from the lab? Beaker. Beaker Zott. Or maybe something that actually meant chemistry-something like, well, Chem? But Kim. Like Kim Novak, his favorite actress from The Man with the Golden Arm. Kim Zott.

No. Kim was too short.

And then he thought, What about Madeline? Elizabeth had read him Remembrance of Things Past-he couldn't really recommend it— but he had understood that one part. The part about the madeleine. The biscuit. Madeline Zott? Why not?

"What do you think of the name 'Madeline,'" Elizabeth asked him after finding Proust inexplicably propped open on her nightstand

He looked back at her, his face blank.

Zakia Ch 20: Madeline explains her chalk drawings of stick figures to her mother, Elizabeth.

My picture," she said, placing it on the table in front of her mother as she leaned up against her. It was another chalk drawing – Madeline preferred chalk over crayons – but because chalk smudged so easily, her drawings often looked blurry, as if her subjects were trying to get off the page. Elizabeth looked down to see a few stick figures, a dog, a lawn mower, a sun, a moon, possibly a car, flowers, a long box. Fire appeared to be destroying the south; rain dominated the north. And there was one other thing: a big swirly white mass right in the middle.

"Well," Elizabeth said, "this is really something. I can tell you've put a lot of work into this."

Mad puffed her cheeks as if her mother didn't know the half of it.

Elizabeth studied the drawing again. She'd been reading Madeline a book about how the Egyptians used the surfaces of sarcophagi to tell the tale of a life lived— its ups, its downs, its ins, its outs— all of it laid out in precise symbology. But as she read, she'd found herself wondering did the artist ever get distracted? Ink an asp instead of a goat? And if so, did he have to let it stand? Probably. On the other hand, wasn't that the very definition of life? Constant adaptations brought about by a series of never-ending mistakes? Yes, and she should know.

…

"Tell me about these people," she said to Mad, pointing at the stick figures.

"That's you and me and Harriet," Mad said. "And Six-Thirty. And that's you rowing," she said, pointing to the boxlike thing, "and that's our lawn mower. And this is fire over here. And these are some more people. That's our car. And the sun comes out, then the moon comes out, and then flowers. Get it?"

"I think so," Elizabeth said. "It's a seasonal story."

"No," Mad said. "It's my life story."

Elizabeth nodded in pretend understanding. A lawn mower?

"And what's this part?" Elizabeth asked, pointing at the swirl that dominated the picture.

"That's the pit of death," Mad said.

Elizabeth eyes widened in worry. "And this?" She pointed at a series of slanty lines. "Rain?"

"Tears," Mad said.

Elizabeth knelt down, her eyes level with Mad's. "Are you sad, honey?"

Mad placed her small, chalky hands on either side of her mother's face. "No. But you are."

Pamela – Ch 27: Harriet and Zott discuss the differences between men and women.

"You know what I mean," Harriet said. "You're smart. It might be off-putting to Mr. Pine, or that Lebensmal person. You know how men are."

Elizabeth considered this. No, she did not know how men were. With the exception of Calvin, and her dead brother, John, Dr. Mason, and maybe Walter Pine, she only ever seemed to bring out the worst in men. They either wanted to control her, touch her, dominate her, silence her, correct her, or tell her what to do. She didn't understand why they couldn't just treat her as a fellow human being, as a colleague, a friend, an equal, or even a stranger on the street, someone to whom one is automatically respectful until you find out they've buried a bunch of bodies in the backyard.

Harriet was her only real friend, and they agreed on most things, but on this, they did not. According to Harriet, men were a world apart from women. They required coddling, they had fragile egos, they couldn't allow a woman intelligence or skill if it exceeded their own. "Harriet, that's ridiculous," Elizabeth had argued. "Men and women are both human beings. And as humans, we're by-products of our upbringings, victims of our lackluster educational systems, and choosers of our behaviors. In short, the reduction of women to something less than men, and the elevation of men to something more than women, is not biological: it's cultural. And it starts with two words:

pink and blue. Everything skyrockets out of control from there."

Speaking of lackluster educational systems, just last week she'd been summoned to Mudford's classroom to discuss a related problem: apparently Madeline refused to participate in little girl activities, such as playing house.

"Madeline wants to do things that are more suited to little boys," Mudford had said. "It's not right. You obviously believe a woman's place is in the home, what with your"

-she coughed slightly— "television show. So talk to her. She wanted to be on safety patrol this week."

"Why was that a problem?"

"Because only boys are on safety patrol. Boys protect girls. Because they're bigger."

"But Madeline is the tallest one in your class."

"Which is another problem," Mudford said. "Her height is making the boys feel bad."

KumKum – Ch 29: A woman homemaker in the live audience of Supper at Six is inspired to follow her dreams to become a heart surgeon

"I'm Mrs. George Fillis from Kernville," the woman said nervously as she stood up, "and I'm thirty-eight years old. I just wanted to say how much I enjoy your show. I ...

I can't believe how much I've learned. I know I'm not the brightest bulb," she said, her face pink with shame, "that's what my husband always says— and yet last week when you said osmosis was the movement of a less concentrated solvent through a semipermeable membrane to another more concentrated solvent, I found myself wondering if ...

well

"Go on."

"Well, if my leg edema might not be a by-product of faulty hydraulic conductivity combined with an irregular osmotic reflection coefficient of plasma proteins. What do you think?"

"A very detailed diagnosis, Mrs. Fillis," Elizabeth said. "What kind of medicine do you practice?"

"Oh," the woman stumbled, "no, I'm not a doctor. I'm just a housewife."

"There isn't a woman in the world who is just a housewife," Elizabeth said. "What else do you do?"

"Nothing. A few hobbies. I like to read medical journals."

"Interesting. What else?"

"Sewing."

"Clothes?"

"Bodies."

"Wound closures?"

Yes. I have five boys. They're always tearing holes in themselves.",

"And when you were their age you envisioned yourself becoming—"

"A loving wife and mother."

"No, seriously—"

"An open-heart surgeon," the woman said before she could stop herself.

The room filled with a thick silence, the weight of her ridiculous dream hanging like too-wet laundry on a windless day. Open-heart surgery? For a moment it seemed as if the entire world was waiting for the laughter that should follow. But then from one end of the audience came a single unexpected clap —immediately followed by another— and then another—and then ten more— and then twenty more and soon everyone in the audience was on their feet and someone called out, "Dr. Fillis, heart surgeon," and the clapping became thunderous.

"No, no," the woman insisted above the noise. "I was only kidding. I can't actually do that. Anyway, it's too late."

"It's never too late," Elizabeth insisted.

"But I couldn't. Can't."

"Why."

"Because it's hard."

"And raising five boys isn't?"

The woman touched her fingertips to the small beads of sweat dotting her forehead. "But where would someone like me even start?"

"The public library," Elizabeth said. "Followed by the MCATs, school, and residency."

The woman suddenly seemed to realize that Elizabeth took her seriously. "You really think I could do it?" she said, her voice trembling.

"What's the molecular weight of barium chloride?"

"208.23."

"You'll be fine."

"But my husband-"

“Is a lucky man. By the way, it’s Free Day, Mrs. Fillis,” Elizabeth said, "something my producer just invented. To show our support for your fearless future, you'll be taking home my chicken pot pie. Come on up and get it.”

Joe Ch 30: The bullying boss of the KCTV faints when Zott brandishes a knife

"As for the complaints," she acknowledged. "We've had a few. But they're nothing compared to the letters of support. Which I didn't expect. I have a history of not fitting in, Phil, but I'm starting to think that not fitting in is why the show works."

"The show does not work," he insisted. "It's a disaster!" What was happening here? Why did she keep talking as if she wasn't fired?

"Feeling like one doesn't fit is a horrible feeling," she continued, unruffled. "Humans naturally want to belong— it's part of our biology. But our society makes us feel that we're never good enough to belong. Do you know what I mean, Phil? Because we measure ourselves against useless yardsticks of sex, race, religion, politics, schools. Even height and weight"

"What?"

"In contrast, Supper at Six focuses on our commonalities— our chemistries. So even though our viewers may find themselves locked into a learned societal behavior – say, the old 'men are like this, women are like that' type of thing— the show encourages them to think beyond that cultural simplicity. To think sensibly. Like a scientist."

Phil heaved back in his chair, unfamiliar with the sensation of losing.

"That's why you want to fire me. Because you want a show that reinforces societal norms. That limits an individual's capacity. I completely understand." Phil's temple began to throb. Hands shaking, he reached for a pack of Marlboros, tapped one out, and lit it. For a moment all was quiet as he inhaled deeply, the radiant end emitting the smallest crackle, like a doll's campfire. As he exhaled, he studied her face. He got up abruptly, his body vibrating with frustration, and strode over to a sideboard littered with important-looking amber whiskeys and bourbons. Grabbing one, he tipped it into a thick-walled shot glass until the liquid hit the rim and threatened to spill over. He threw it down his throat and poured another, then turned to look at her. "There's a pecking order here," he said. "And it's about time you learned how that works."

She looked back at him, nonplussed. "I want to go on record saying that Walter Pine has been absolutely tireless in his efforts to get me to follow your suggestions. This is despite the fact that he, too, believes the show could and should be more. He shouldn't be punished for my actions. He's a good man, a loyal employee." At the mention of Walter, Lebensmal set down his glass and took another drag off his cigarette. He didn't like anyone who questioned his authority, but he could not and would not tolerate a woman doing so. With his pinstriped suit jacket parted at the waist, he locked his eyes on her, then slowly started to undo his belt. "I probably should have done this from the very beginning," he said, snaking the belt from its loops. "Establish the ground rules. But in your case, let's just consider this part of your exit interview."

Elizabeth pressed her forearms down on the armchair. In a steady voice she said, "I would advise you not to get any closer, Phil."

He looked at her meanly. "You really don't seem to understand who's in charge here, do you? But you will." Then he glanced down, successfully freeing the button and unzipping his pants. Removing himself, he stumbled over to her, his genitals bobbing limply just inches from her face.

She shook her head in wonder. She had no idea why men believed women found male genitalia impressive or scary. She bent over and reached into her bag.

"I know who I am!" he shouted thickly, thrusting himself at her. "The question is, who the hell do you think you are?"

"I'm Elizabeth Zott," she said calmly, withdrawing a freshly sharpened fourteen-inch chef's knife. But she wasn't sure he'd heard. He'd fainted dead away.

Geetha – Ch 41: Zott gives an inspirational farewell speech to her TV audience.

"I've very much enjoyed my time as the host of Supper at Six," Elizabeth continued, looking steadily into the camera, "but I've decided to return to the world of scientific research. I want to take this opportunity to thank you all not only for your viewership," she said, increasing her volume to be heard over the hubbub, "but also for your friendship. We've accomplished a lot together in the last two years. Hundreds of meals, if you can believe that. But supper isn't all we've made, ladies. We've also made history."

She took a step back, surprised, as the audience rose to its feet, roaring its agreement.

"BEFORE I GO," she shouted, "I THOUGHT YOU'D BE INTERESTED TO HEAR-" She held up her hands to quiet the audience. "Does anyone remember a Mrs.

George Fillis— the woman who had the audacity to tell us she wanted to become a heart surgeon?" She reached into her apron pocket and pulled out a letter. "I have an update. It seems that Mrs. Fillis has not only completed her premed studies in record time but has also been accepted to medical school. Congratulations Mrs. George-no,

I'm sorry – Marjorie Fillis. We never doubted you for a second."

With that news, the audience instantly regained its vigor, and Elizabeth, despite her normally serious demeanor, pictured Dr. Fillis scrubbing in and could not help it. She smiled.

"But I'm betting Marjorie would agree," Elizabeth said, raising her voice again, "that the hard part wasn't returning to school, but rather having the courage to do so." She strode to her easel, marker in hand. CHEMISTRY IS CHANGE, she wrote.

"Whenever you start doubting yourself," she said, turning back to the audience, "whenever you feel afraid, just remember. Courage is the root of change – and change is what we're chemically designed to do. So when you wake up tomorrow, make this pledge. No more holding yourself back. No more subscribing to others' opinions of what you can and cannot achieve. And no more allowing anyone to pigeonhole you into useless categories of sex, race, economic status, and religion. Do not allow your talents to lie dormant, ladies. Design your own future. When you go home today, ask yourself what you will change. And then get started."

.png)

%20rows%20in%20a%20pair%20with%20Calvin%20Evans%20(Lewis%20Pullman).png)

,%20an%20older%20neighbor%20who%20had%20already%20raised%20a%20few%20children,%20took%20on%20a%20familial%20role%20that%20allowed%20Zott%20to%20continue%20working%20as%20the%20sole%20provider%20for%20herself%20and%20Madeline%20Zott.png)

%20in%20Supper%20at%20Six,%20her%20cooking%20show%20turned%20into%20chemistry%20class.png)

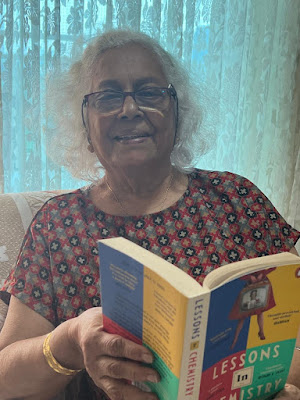

I read Lesson In Chemistry two years ago, loved it. Loved the story, loved the writing style of the author and immediately thought we must read the book with KRG. I was happy to select the book for KRG's November Session. Our readers turned the reading experiences of the book so much better. They found out so many nuances of the story and found ways to relate them to their personal experiences.... it was a fun session. Thank you Joe and Geetha for putting together such an authentic blog representation of the session on November 22, 2024.

ReplyDelete