Charlotte Brontë wrote the novel Jane Eyre and published it in 1847 under the male pseudonym, Currer Bell. It became a classic of literature over the years, both for its tender love story and its portrayal of a fiercely independent woman who would not brook male patriarchy, or other kinds of domination by family members, school directors, upper class nobility, and assorted tyrants and bullies. As the novel makes clear the qualities genteel women were expected to master were only these – stitching, playing the piano, reading and speaking French, and painting.

Ultimately, a novel depends on strong portrayal of its cast of characters, and Charlotte Brontë gave to each of them the coloration of a novelist who enters into the story and creates vibrant portraits of villains, heroes, and the miscellaneous folk who play their role in what is now labelled as a Bildungsroman, a novel that runs the course of a person’s formative years and development. Jane Eyre has become an essential part of English literature and this exposition by Benjamin McEvoy is an excellent introduction, to what he calls “one of the most riveting love stories ever penned in English Literature.” It also takes you on the journey of Charlotte Brontë’s life story, which is partly sublimated in the novel.

Of course, novelists base a lot writing on their life experiences, but they live a rich inner life too in the imagination; they also borrow from what they read. There’s clear evidence in Jane Eyre that Charlotte Brontë not only read a lot, but her mind became a storehouse of words from her wide reading. One of her correspondents a gentlemen called George Lewes (partner of Mary Evans, i.e George Eliot) advised her to eschew imagination in favour of life experience. Here was her answer:

Imagination is a strong, restless faculty, which claims to be heard and exercised: are we to be quite deaf to her cry, and insensate to her struggles? When she shows us bright pictures, are we never to look at them, and try to reproduce them? And when she is eloquent, and speaks rapidly and urgently in our ear, are we not to write to her dictation?'

We have Gothic elements too in Jane Eyre. The first premonition is the strange shrieking at night from the attic which forebode a disaster in the making.

This was a demoniac laugh—low, suppressed, and deep—

The summoning of Jane from the remote moor dwelling of the Rivers siblings with a call ‘Jane! Jane! Jane!’ while the candle was dying and the room was full of moonlight, leads to the ultimate reconciliation with Rochester.

What about the language of the novel? It has a tendency to be Latinate and elevated with a vocabulary that forces a modern reader to reach for the dictionary often. The sentence structures are intricate and impart a formal tone that requires some getting used to. An appeal to one of the Large Language Models (LLMs) elicited ~100 words that are now archaic, obsolete, or rare in usage in modern English. Joe could find another 35 examples, besides, from his own notes while reading. Jane Eyre is a hothouse of rare plants that have to be observed, savoured and studied. It’s no Mills & Boon romp.

Major influences are evident of the Bible and Shakespeare, two venerable sources that English authors mine. Often she uses the Bible to point out the hypocrisy of pontificating characters like Mr Brocklehurst who tirelessly quote scripture in defence of ill-treating children in Lowood School. But the most elemental use of the Bible by Charlotte Brontë, goes all the way back to Genesis and the words ‘ help meet for him (Adam)’ as a definition of woman. The absolute rejection of this imposed status governs Jane’s rejection St. John’s suit.

Significant hints of Shakespearean characters are sprinkled in Jane Eyre. For instance, Bertha Mason (the ghostly presence in the attic) prowls at night in the upper rooms like Lady Macbeth sleepwalking in her guilt. Rochester resembles King Lear, beginning in arrogance, and suffering losses (Rochester’s blindness/maiming; Lear’s madness), until he achieves humility through suffering.

A fitting summation would be this quotation from Chapter 33 when Jane spurns Rochester’s portrayal of her as a captive bird before she departs:

“I am no bird, and no net ensnares me; I am a free human being with an independent will, which I now exert to leave you.”

Charlotte Brontë died in 1855 aged 38 – her likeness was captured by the artist George Richmond

Zakia – Intro to the author Charlotte Brontë

Zakia thought everyone quite enjoyed this book. Though most had read it in their youth, it was enjoyable even on a second reading .

Charlotte Brontë was born on 21st April, 1816 in Thornton, Yorkshire, England. She was an English novelist and poet best known for her classic novel Jane Eyre published in 1847 under the pseudonym Currer Bell.

She was the third of six children born to Maria Branwell and Patrick Brontë, an Irish clergyman. Her siblings included Anne Brontë who wrote Agnes Grey, and Emily the author of Wuthering Heights.

In 1820 the Brontës moved to the village of Haworth on the edge of the moors where her father had been appointed as perpetual curate of St. Michael and All Angels Church.

She lost her mother at the age of five, following which the loss of her two older sisters during a typhoid outbreak which swept through their boarding school, left her bereft. After a difficult childhood Charlotte was educated in various schools and later worked as a teacher and governess. Haworth was a cesspool of illnesses, and historians have speculated that these factors contributed to the early death of the Brontë sisters.

She was admitted to Coventry, a school similar to Lowood in the novel. In 1842 Charlotte joined the Pensionnat Héger in Brussels, a girls' boarding school where she and her sister Emily studied in order to improve their French and teaching skills. Charlotte Brontë made this school the inspiration for the setting of her novel Villette.

Charlotte fell in love with the school's director, Constantine Hager, who inspired the character of Rochester. It is said that ‘fiction is a lie which tells the truth.’

She began writing early, creating elaborate imaginary worlds in concert with her sisters, Emily and Anne. In 1846 the sisters published a collection of poems under pseudonym Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell. Women writers at that time preferred to keep a pen name, to avoid prejudice. For some time, no one knew who the Brontë sisters were. Charlotte’s first novel, Professor was rejected and later published posthumously. Her second novel, Jane Eyre, was published in 1847 by Smith, Elder & Co. of London. The first American edition was published in January 1848 by Harper & Brothers of New York. She later wrote Shirley (1849) and Villette (1853).

Narrated in the first person point Jane Eyre remains one of the most influential works of English literature. Charlotte’s prose is rich, introspective and emotionally intense. She offers deep insights into Jane’s mind allowing the reader to connect with her inner world. Her use of extraordinary imagery stands out in this classic masterpiece which still holds appeal for a wide range of audiences.

All through one feels Jane is thinking aloud about her feelings.

Charlotte Brontë was celebrated for the emotional depth with which she endowed Jane. Her strong advocacy for women’s autonomy was another significant contribution. She has used extraordinary imagery employing everyday language for the most part.

She was married to Arthur Bell Nicholas in 1859. But died a year later at the age of 38, with a still unborn child.

Jane Eyre is a work of artistic genius, where the novel becomes an extension of self. The heroine is a plain woman like herself. The novel gave new truthfulness to Victorian fiction. Jane Eyre is not just a love story. It is a profound exploration of identity, integrity and self respect. It falls under the literary genre, Bildungsroman, German for a novel about the moral and psychological growth of the main character from childhood to adulthood.

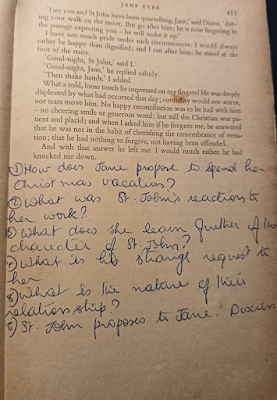

A page about St. John and Jane from Devika’s copy of Jane Eyre when she was studying in the 1st Year of B.Sc. – ‘cordiality would not warm him nor tears move him’

Devika said her impression is so different now than when she read it in college. It was like she was reading a different book totally. She held up her copy during the Zoom session, full of pencilled notes; it was later borrowed by her book-loving daughter, Smriti.

Saras – Charlotte Bronte‘s Jane Eyre, A Review with spoilers

When Saras read the book at the age of 15, she fell in love with the main characters, Jane and Mr. Rochester. Their love story was the central focus and the world was a rosy place because they found each other in the end after some trials, and lived happily ever after.

Reading it later in life raised many questions: especially the disparity in age between the worldly-wise and well-travelled Rochester, over forty years in age, overawing the young Jane.

“I am near nineteen, but I am not married. No.” she tells her cousins Diana, Mary, and St John.

She has grown up protected and shielded in a school and has not stepped out alone until she leaves it to take up her job as Adele’s governess. No wonder she is intimidated by Rochester and hero-worships him. But Rochester is not one to be worshipped; he is married and has kept his wife in hiding from the world in the attic because she is mad. He married for money – it matters little that his father and brother arranged the marriage, for he did go through with it of his own volition! And when his wife descends into madness, he keeps her locked up without letting the world know. Even that might be forgiven him – it was a world where divorce was an impossibility; marriage was considered a bond for life. What is despicable is that he is ready to commit bigamy and marry Jane without telling her about the wife he has secreted in the attic. Jane, however shielded she was growing up, is one of the most assertive women characters in English Literature; when she learns the truth, she refuses him and fearing she may give in willy-nilly, runs away from Thornfield.

Here the Gothic features of the story take hold. Wandering in the countryside without money, and close to starvation, who does she stumble on but her own cousins of whose existence she had no idea. Of course, this fantastic coincidence is revealed later in the story and matters move in such a way that penurious Jane is left with a huge fortune from an uncle, which she then generously shares with her cousins. Jane now has money and family; in a paraphrase of Jane Austen one could say, “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single woman in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a husband.”

She rejects St John’s proposal of marriage to move to India as a missionary. As a strong woman she refuses to enter the married state as a mere ‘helpmeet’ to a man. She must be acknowledged and loved for her own worth. At a time when marriage was seen as the pinnacle of a woman’s existence, this refusal stands out as a proclamation of her independence.

“He has told me I am formed for labour – not for love, it follows that I am not formed for love: which is true, no doubt. But, in my opinion, if I am not formed for love, it follows that I am not formed for marriage. Would it not be strange, Die, to be chained for life to a man who regarded one but as a useful tool?”

Off she goes in search of Rochester because she hears him calling her mysteriously and telepathically above the wind and storm. All is forgiven and the couple is reunited because the mad Mrs Rochester meanwhile has made her exit in a fire, causing Rochester to lose his eyesight. Of course, our hero cannot be punished forever; hence towards the end of the story we learn he is slowly regaining some sight.

It is fantastic as a romance, and Gothic in style, but what really stood out for Saras was Charlotte Brontë’s writing. Though very Latinate in diction and elevated in language, the descriptions of nature are vivid and enchanting:

Over the hilltop above me sat the rising moon; pale yet as a cloud, but brightening momentarily; she looked over Hay, which, half lost in trees, sent up a blue smoke from its few chimneys; it was yet a mile distant, but in the absolute hush I could hear plainly its thin murmurs of life. My ears too felt the flow of currents; in what dales and depths I could not tell: but there were many hills beyond Hay, and doubtless many becks threading their passes. That evening calm betrayed alike the tinkle of the nearest streams, the sough of the most remote.

However, the unfamiliar vocabulary will pose some difficulty for modern readers.

Brontë was the daughter of a clergyman and her deep connection with God is evident in the book. The God she sees is in Nature:

"Night was come, and her planets were risen: a safe, still night; too serene for the companionship of fear. We know that God is everywhere; but certainly, we feel his presence most when His works are on the grandest scale spread before us; and it is the unclouded night-sky, where His worlds wheel their silent course, that we read clearest His infinitude, His omnipotence, His omnipresence...I felt the might and strength of God."

Brontë’s struggle for women’s equality in an age when feminism was unknown comes through strongly in Jane’s character.

Women are supposed to be very calm generally: but women feel just as men feel; they need exercise for their faculties, and a field for their efforts as much as their brothers do; they suffer from too rigid a restraint, too absolute a stagnation, precisely as men would suffer; and it is narrow-minded in their more privileged fellow creatures to say that they ought to confine themselves to making pudding and knitting stockings, to paying on the piano and embroidering bags, It is thoughtless to condemn them, or laugh at them, if they seek to do more or learn more than custom has pronounced necessary for their sex.

The biases of the time, the hierarchy built into social tradition, and the prejudice against the working class is evident in the book. Jane’s father’s family is shunned because they are poor – her aunt calls her uncle “a sneaking tradesman.” Jane herself shows a bit of class condescension towards little Adele “… not rebuking even some little freedoms and trivialities into which she was apt to stray when much noticed, and which betrayed in her a superficiality of character, inherited probably from her mother, hardly congenial to an English mind.”

Reading Jane Eyre may amount to indulging in a huge Mills & Boon orgy for many women readers. Those who had memories of reading it in their teens had quite different questions and a more expansive view when they read it in their maturity for the July 2025 reading at KRG. Jane Eyre is a book every keen reader should encounter in their teen years, and then again later in life, when one is blessed with richer veins of experience.

Now to the readings and discussions.

Saras

Ch 2 Jane Eyre is locked up in the Red Room by her aunt Mrs Reed as punishment for defending herself against her cousin John Reed's bullying.

Because of Jane’s pugnacious reaction, finally she is sent to the Lowood boarding school; this is an important turning point in her life.

Bessie the maid played by Caitlin Brennan tries to wake Jane Eyre (Trinity Smith) after she collapses in the Red Room

Jane thinks that the ghost of her uncle who died in this very room is haunting her; she was only ten then. Even in the end when she confronts her aunt, who had withheld the inheritance letter from her other uncle in Madeira, Mrs Reed doesn't feel any remorse. A very hard-hearted the aunt she is.

At the end, when Mrs Reed on her deathbed sends for Jane to give her that letter, she remains unforgiving. She was very jealous of the little girl, because her late husband, Jane’s uncle, was very fond of her. Mrs Reed felt that her son John was the ultimate good guy and pampered him.

Pamela went next, because she had an engagement, although her piece from Ch 26 comes well past the middle of the novel.

Pamela

Ch 26 Mr Rochester narrates to Jane the story of his marriage to Bertha Mason a moneyed girl of some beauty in Jamaica, who turned out to be from a line of mad people on her mother’s side.

Pamela chose this passage because the review of this book said that the themes in this book are very relevant even now, after so many years. These kind of family quarrels regarding property are relevant to what goes on in Kerala, or for that matter, everywhere in the world.

Two centuries after such a book having been written to revolutionise attitudes, people haven't changed.

Another thing that drew Pamela to this passage was that Jane and Mr Rochester have totally different backgrounds. Both are looking for true love because their experiences have left them lonely, one because he was unwanted and didn't have a family, the other, because she was not loved even though she was brought up by her aunt in a family of cousins.

All the characters are in search of true love and loyalty. Pamela felt Jane and Mr Rochester understood each other; the pain that each had suffered drew them together.

The compassion shown by Jane Eyre and her willingness to sacrifice for Mr Rochester was because she understood his background. The kind of duping Mr Rochester did to Jane happens commonly to women, and some men as well. The Russian queen Catherine the Great, who overthrew her husband, Peter III, to become the Empress of Russia, had a deeply troubled marriage, with Peter who displayed erratic and often cruel behaviour; he was a bit off his rocker. He had to be deposed by Catherine.

KumKum thought Rochester’s action was no way to treat a mad person, locking her up in an attic. She went around laughing like a demented ghost. Mr Rochester had another house, where he lived when this house was burnt down; that is where she could have stayed from the beginning, according to KumKum.

Th mad woman, Bertha Mason, almost incinerated Mr Rochester, and attacked her own brother. Jane Eyre saved Mr Rochester from almost certain death. Why couldn't Mr Rochester have divorced Bertha Mason, Joe asked? He didn't need the £30,000 dowry she brought; it was his father who was plotting for it.

So if he was fed up with her, and he realised this very soon after their honeymoon, he could have just put her away. But he had to honour his commitment and stick to traditions, replied Saras.

Divorce must have been a big word at that time, very difficult to accomplish. It might have been a big word for women, said Joe. Women didn't have many rights in England right up until the twentieth century. They were considered the chattel of men, first of their fathers, and later of their husbands.

Women got the vote in England only in 1928. If nothing else Mr Rochester could have walked away. The church allowed divorce, on the basis of concealment of madness or incurable insanity; this is certainly true for the Church of England latterly, but what was it the rule in olden times?

Could the marriage not have been annulled? Anyway, it was a Gothic novel. So Bertha Mason had to live within the household, to provide the drama and horror.

Vivienne Haigh-Wood, unhappy, unwell and possibly suffering from bipolar disorder she was confined to a mental asylum and died there of a heart attack

Think of modern examples. T.S. Eliot married Vivien Haigh-Wood in 1915, but their relationship was marked by significant unhappiness and a decline in her mental health, eventually leading to her being committed to a mental asylum in 1938, where she remained until her death in 1947. Eliot didn't marry again until she was dead.

Knowing that Bertha Mason, his wife, is living in that house, did not prevent Rochester from wooing a younger woman. That is the most irregular thing. Had he married Jane Eyre, the marriage would not have been legal and he would have been accused of bigamy, a crime in England at the time.

Devika brought up the matter of her cousin, Usha Kutty, 1988 alumna of Smith College, Massachusetts. She took up the cause of the poet Rebecca Elson whom Priya recited at the last poetry session;

Smith College has the Boutelle-Day Poetry Center at

And a site with photos and bios of poets who were alumnae of Smith:

Rebecca Elson is missing from that site, although she too was a distinguished alumna of Smith.

Devika’s cousin, Usha, inspired by Priya’s celebration of Rebecca Elson, faithfully recorded for posterity on our blog, has been in correspondence with Jennifer Blackburn who curates the Smith Poets site to see if they could induct Dr. Elson, the astronomer-poet. Ms Usha cited our blog as proof that Rebecca Elson deserved to be included on the Smith College site for poets. Because Priya discovered Rebecca Elson via the the Maria Popova blog and our blog recorded the reading and biography, Deviha referred it to her cousin ,who is a ‘proud alumna’ of Smith. KRG could be instrumental in Smith ultimately recognising Dr. Elson on their official web site for poetry..

Usha was very kicked when she saw our blog – her comment: “goodness, you guys cover a lot of material! What a thorough write-up.”

Smith is trying to contact the Elson family and see whether they can add her to their poets list. What is the necessity of consulting Elson’s family, for she is a public figure and her poetry is in the public domain. Smith would only be presenting published information about the astronomer-poet, not her private matters.

KumKum mentioned a number of people across the world for whom the KRG blog was a connector to renew old contacts. She gave examples of Tom Duddy’s erstwhile colleagues in Italy and New York State, and Talitha’s friends from Women’s Christian College, Madras, etc.

Devika said it was amazing how one poet came up at our session in Kochi, and it's gone all the way to roiling Smith College in Massachusetts, USA.

Joe pointed out we maintain a record – what we discuss doesn't just vanish in the air when the session is over. That's rather unusual. Our public record of readings has been maintained over the past twenty years.

“Also, it is very well written, Joe. It's fantastic,” someone said. The last one was fantastic, according to the interlocutor.

Arundhaty

Saras read about how Jane was punished in the Red Room at her aunt Mrs Reed’s home and then because she rebels, she is sent off to Lowood School. Arundhaty read from Ch 10 where Jane who became a teacher at the school after matriculating decides it’s time she left for better opportunities.

Jane figures out how she can help herself by moving out of Lowood and finding a new position. She advertises in the newspaper for a position as a governess.

What Arundhaty really liked about this passage was the thought:

Any one may serve: I have served here eight years; now all I want is to serve elsewhere. Can I not get so much of my own will? Is not the thing feasible?

She was not asking for Liberty, Excitement, Enjoyment – just to be able to serve somewhere else. A step forward to escape being stuck in Lowood School.

She manages to figure out how to do it all by herself without help from anyone. She is asserting her independence. Right from the start she comes out as a girl with head on her shoulders. Her circumstances were bad. But somehow she had her priorities right and could extricate herself.

Jane Eyre advertises for the position of governess

In the choices she makes later in life, whether to marry Rochester or marry the other sanctimonious missionary – she knew what she wanted. When Rochester is wooing her she exercises restraint, following the advice of Mrs Fairfax:

but believe me, you cannot be too careful. Try and keep Mr. Rochester at a distance: distrust yourself as well as him. Gentlemen in his station are not accustomed to marry their governesses.

She weighs every move. Even when St. John Rivers saved her, she doesn't fall for him headlong.

Mr. Rochester proposing to her in the garden, she considered as a consummation she desired. It would be a true union between equals. She could not think of marrying St. John on the other hand, because he did not consider her worth anything, except as a labourer in the vineyard of Christ.

Thomo read from Ch 12 where Mr Rochester is returning to Thornfield on his horse and comes a cropper; he has to be helped home by young Jane.

The bit Thomo read is Jane's first meeting with Mr. Rochester. It happens on the moors; she's gone out for a walk and sees a rider passing by and the horse takes fright and trips. The rider falls and Jane helps him up.

This is the first meeting and they meet as social equals, not as employer and employee, later on. They meet as equals at the beginning of the book; and at the end of the book, again, because of Rochester's reduced circumstances, and her circumstances having improved through the windfall inheritance from her uncle, who had prospered in Madeira, the Portuguese island famous for its fortified wine by that name.

It's only after this encounter they realise that he is the master of Thornfield and her employer.

KumKum said he was not a nice master at the beginning; he was peremptorily commanding her to come here, sit there, show her artwork, etc – he was a bit of a tyrant.

The author wanted to paint him like that, as a brusque man who was probably still suffering from all the ill-effects of his marriage and isolated, with little company of his status and accomplishment to talk to.

He must have also been quite embarrassed to seek the help of a woman when he fell off the horse. This type of situation is presented even in Wuthering Heights and in Thomas Hardy's novels, said Priya. In Wuthering Heights, the meeting with Mr Heathcliff is somewhat like this on the moor.

One of the mysteries at the beginning of the book is not knowing what all the shrieking and howling from the attic in Thornfiled Hall is about.

There’s a hint of Rebecca, the novel by Daphne du Maurier. These Victorian novels are full of sudden windfall inheritances. Some uncle or aunt fills your pocket with a lot of money without the protagonists even being aware who that person is. It was a frequent occurrence in novels of those times. People also died unexpectedly in those days.

There's a lot of thunder and lightning and the wind at critical points serves to enhance the atmosphere .

Beads and such can be part of family heirlooms, passed down through generations. If you have a bead necklace or bracelet with a known history, it could lead to information about the individuals who owned it and their place in your family tree. All that's gone now but in those days, among a certain class it was known.

The upper classes had their genealogy written down. You knew who your relations were. You may not have met them but they were there.

The Bible is filled with genealogies. In England and in the Christian church in Kerala, you have the marriage certificates and the baptism, baptismal records, marriage records, death, everything is preserved.

In those days, communication was less secure. Somebody went off to the West Indies and made a lot of money and then, after years, he died there and then willed it to somebody.

The French colonials begat little children in their colonies, and they often bequeathed their fortune to illegitimate children, as in the case of Alexandre Dumas. His mother was a slave, and father a general in the French army. Alexandre got a lot of the old man's money. That's why he was able to live in Paris and study in good schools.

The Pandas or priests, if you go to Bodh Gaya and places like that, also have records. Yes, in Banaras, they maintain your family tree somehow. They have it all written.

How do they know? You need to take their permission to get married maybe. In those days a lot of it was kept in the memory of these people.

If you read Alex Haley's historical novel Roots, (the hero is Kunta Kinte) Haley goes and meets a griot (oral historians who are trained from childhood to memorise and recite the history of a particular village). The griot is named Kebba Kanji Fofana. After about two hours of "so-and-so took as a wife so-and-so, and begat...", Fofana reached Kunta Kinte. See:

Fofana relates that Kunta Kinte went off and never returned. He was abducted by black slave traders. That was Alex Haley's ancestor. Thus the history was kept in memory by professional griots and recited orally.

Devika said in Tamil Nadu, they practice Nadi Jothidam, also known as Nadi Astrology, which is an ancient form of astrology based on the belief that an individual's life details are recorded on palm leaves (Nadi leaves) by sages. Apparently these men will pick out a palm tree and tell you about your complete past. Don’t know how they pick out the particular palm leaf just by looking at your face. They will tell you your name, your parents name and various things. If you have any problem, they tell you what to do. Anybody from anywhere.

Doesn’t it sound like a superstitious black art? Astrology strains credibility.

Zakia read from Ch 16 when Jane reflects on her life at Thornfield Hall, and disabuses herself of the notion that Mr Rochester could have a preference for her.

It's the beginning of her tender feelings for him and he compliments her about her eyes and doesn't let go of her hand. There is a little romance building up, or at least some fluttering of the heart. Jane thinks of herself as very plain and just a governess. How can she even presume to be the object of love of her master? She reprimands herself.

She actually undertakes an exercise, of drawing a portrait of a governess (herself) and also of Miss Blanche Ingram, about whom she feels rather jealous. Thus she does a reality check on herself.

Jane drew portraits of herself and Blanche Ingram

She's cool with Mr. Rochester. She never flirts with him. She remains grounded. She's practical. But she really has feelings for Mr. Rochester that come from her heart – that she can't deny.

Joe asked when does Jane admit to her feelings? Probably starts with an admiration for him. She’s awestruck right from the beginning. Will it progress to love?

The competition with Blanche Ingram is deeply present in her mind – her ravishing beauty versus Jane’s talent. Something is germinating in her.

It was such a sweet scene when Rochester puts on a gypsy’s mask. Mr. Rochester disguises himself as a gypsy woman in Chapter 19. He does this to observe Jane and the other guests, and to subtly gauge Jane's feelings for him. He calls particularly for her to come and have her fortune told. But she's hiding away somewhere quietly.

Another turning point in the budding romance is when she saves him from the fire set by the mad woman in Rochester’s bedroom.

Jane is developing confidence in herself, her self-image is slowly rising from that of an orphan and a governess. The status difference with her master, Mr Rochester is daunting. There is also a bit of self-protectiveness. She wanted to prevent herself from falling headlong for him and getting disappointed, and being rejected in the end. Rejection has been the bane of her young life. Mr Rochester however enjoyed her company. He sets store by her common-sense wisdom and listens to her for advice. In that lonely house, he has somebody he can talk to finally.

All the other women were fawning over him, but this young girl kept her distance and spoke with an educated mind. That attracted him.

He spreads a rumour (intending it to travel to the ears of Blanche Ingram) to the effect that he really does not possess much of a fortune. He wants to get rid of her, for he rightly thinks she is merely after his money.

Devika read from Ch 18 where Jane is ignored by Mr Rochester who is wooing the beautiful Miss Ingram sedulously. However, Jane realises Blanche Ingram has defects that disqualify her from being a good bride for Mr Rochester.

Devika was reading what we have just talked about. She’s in love with Mr. Rochester but dares not admit it and feels herself inferior as a mate compared to to the upper-class ladies whom Mr Rochester met in society habitually.

She has doubts about Blanche Ingram, although Mr Rochester

was going to marry her, for family, perhaps political reasons, because her rank and connections suited him;

Yet –

she (Ingram) could not charm him.

Devika said sometimes you think that Jane is like an impartial psychologist viewing the whole scene and declaring her unbiased opinion. She is very much part of the scene and doesn't miss anything. She is minutely observant of every bit of what's happening.

William Hurt as Rochester and Elle Macpherson as Blanche Ingram in Jane Eyre (1996) in a horse-riding scene

Joe mentioned that Devika hadn't met this word contumelious.

Joe felt horrified when he started this novel. What on earth is Charlotte Brontë talking about? Does anybody write like this? Joe was waiting for a reader to remark on the turgid Latinate prose of the author who seemed to delight in fetching rare words from her capacious memory to splurge liberally across the length of this novel, forcing the reader to halt on every page and reach for a dictionary – a large unabridged one, for it was unlikely the Concise Oxford Dictionary could gets its girth around her outré vocabulary consisting of words like lusus naturae, colloquise, and bombazeen.

Even our formidable Dr Shashi Tharoor would have been at a loss. OMG, what bombastic writing, thought Joe, when he early encountered Mr Brocklehurst sounding off about the virtues of a meagre diet:

Should any little accidental disappointment of the appetite occur, such as the spoiling of a meal, the under or the over dressing of a dish, the incident ought not to be neutralised by replacing with something more delicate the comfort lost, thus pampering the body and obviating the aim of this institution; it ought to be improved to the spiritual edification of the pupils, by encouraging them to evince fortitude under the temporary privation …

Finally, Joe was forced to appeal to one of these AI jobs to cough up all the rare words Miss Brontë used in the novel, but it could not give him half of what he found by his own wading through the novel’s thicket of unfamiliar words.

KumKum confessed she too found many strange words she had never met. They are not in use now. She read the novel in her youth, and read it again, but when asked by Joe, whether she knew what lusus naturae meant, she was at a loss. Then he asked her whether she had bothered to look up gräfinnen? There's a lot of French and some German sprinkled in the book.

The passage which Thomo read had that word, Gytrash, which is actually a legendary figure in Northern England, a spirit appearing as a dog or horse that haunts lonely roads; it is supposed to waylay travellers. If it's a good one, it'll take you to your destination, if not, it leads you astray.

There are some supernatural elements. Jane keeps imagining there's a ghost, and of course, later you know who is stalking the house. That mansion gives you that sombre feeling that it's all dark, the moors, the trees, the birds. Anything can appear out of the blue and the unforeseen can happen.

Right from the time Jane was small, she had these vivid imaginations. Just think of a little girl being locked up in that Red Room, and how that would have scarred her for life. She's afraid of her aunt, Mrs Reed, also.

The book was one great orgy of Mills & Boon. Millions of women across the globe have been entranced by M&B books, reaching into their handbags to spend a few hours transported into a fantasy world of intrigue and gentle romance. One woman reader said M&B was the soft porn for women, and it was so ‘nice.’ It’s been a decade since a string of authors was lined up to furnish the same exhilaration for Indian women in multiple languages.

Modern M&B language have these general features:

Passionate descriptions – Her heart pounded like a wild thing trapped in her chest

Physical descriptions – chiselled jaw, curves in all the right places, etc

Intimacy – waves of pleasure

Clichés – She knew she should resist, but her traitorous body responded

Luxurious settings – Italian villas, tropical beaches, corporate boardrooms, etc.

The language is designed to evoke fantasy and provide a gentle catharsis. Devika’s Jane Eyre passage was a vintage M&B moment.

KumKum faithfully read the book, didn’t want any intrusions, and incurred no disturbance. However she passed over the snatches of French and German. Joe enjoyed the book, in spite of his early protestations.

In her passage from Ch 23 Jane and Mr Rochester drop their reserve in the garden. Jane feels he has already chosen Miss Ingram for wife and so she should leave, but he declares his love for Jane. What! did she say, ‘wife’? She as wife, is a commitment in words by Rochester.

She says she loves him, but because she didn’t have money she could not consider it. Except for the money matter she would not have let him go. But she does not consider herself marriageable to him. Rochester declares her as his wife.

“I summon you as my wife.”

She says, you are a married man, or as good as married man, to Blanche Ingram, she imagines. And the irony of it is, during all this time he is actually married to a mad woman in the attic.

He was proposing to Jane while Bertha Mason was living in the house as a ghost. We have our sympathies for him because she's a mad woman. But still, he should have known better. He should have been honest about it. He should have told her about it and come clean. Jane would have understood. She wouldn't have married him, of course. But she would have understood. That was the least he could have done.

They call this ‘grooming’ in today's world, somebody said, where an older man picks on a younger girl and influences her into giving him sexual favours. Isn’t that what they call a ‘sugar daddy’ – a well-to-do older man who supports or spends lavishly on a mistress or a girlfriend?

The real meaning of the word ‘grooming’ is to build a trusting relationship with (a minor) in order to exploit them especially for nonconsensual sexual activity. That’s not what Rochester is doing. Grooming gangs of modern times are quite different.

Joe said he doesn't think this is grooming. This is actually the climax of a romantic scene in the middle of the novel. Rochester’s a bit manipulative.

There are already impediments to his being wed to this girl. But in a garden, with flowers, under the leafy trees with birds chirping, they are warming to each other. And Jane is diffident because Rochester belongs to the upper class. He will only marry a moneyed person, whereas she’s a nobody, an inferior servant in the household. How could Rochester look at her with romantic feelings?

Joe goes to the romantic parts, because he is a romantic, and he selected this passage originally –

Jane Eyre (Mia Wasikowska) in the garden scene with Rochester (Michael Fassbender) from the 2011 film directed by Fukunaka – Budget $35m

The substance of the whole story is a coming together of spirits from opposite ends. KumKum said this would be the sort of scene in a Bollywood film in which the heroine would start dancing under a tree in a saree, not in one saree but in several sarees, changed in succession, and the hero would respond from behind a hillock.

Shoba Ch 28 Jane is fleeing from Thornfield over the bogs and arrives exhausted at the house of the Rivers siblings, Moor House, near the town of Morton.

This scene was very typical of that period – the women gathered at a table in the house doing embroidery. Jane was saved from her terrible condition when she escaped penniless from Rochester’s house and runs away. This home was like a haven of peace after her homeless wanderings on the moor. The Rivers family saved her life and took her in and were kind to her.

Jane talks to St. John Rivers and his two sisters

If you didn't have money in those days, you couldn't get married. Something akin to dowry was required. If not, women had to earn and take care of themselves.

In the end Jane gives the Rivers siblings (brother and two sisters) a share of her uncle’s inheritance and one of them gets married. It was not a society that women thrived in without submitting themselves to a second-class existence. The description Jane renders is while she's looking through the window into the study room of the Rivers household. She guesses at the situation within.

The women were educated at home or by the church, but didn’t have money.

Joe read from Ch 34 where Jane is under pressure from St. John Rivers to go as a missionary’s wife to India. She resists.

Many people have noted that this is a novel where the notion of women asserting their rights comes to the fore. It was unusual for that early Victorian period. The articulation of women’s rights is expressed most assertively in this chapter. Joe chose this passage for that reason. Jane argues and resists St. John’s exhortations that she should become a missionary's wife and accompany him to India.

Notice these old-fashioned words like ‘helpmeet.’ These are from the Bible. It is from the first chapter of the Bible where Adam is created and in Genesis 2:18 we encounter the passage:

“And the Lord God said, it is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him an help meet for him.” [meet (adj) means suitable]

Even in that pre-Victorian society one would not use the word helpmeet. It is a throwback to a biblical an era when woman was seen as a help suitable for a man, therefore, having no worth independent of a man.

‘I can influence efficiently in life and retain absolutely to the death.’ This is how St. John thinks of her, as a fully pliable object in his hands.

Jane turns down St.John's proposal of marriage to go as his 'helpmeet' to India

He is not hiding anything. He is very frank and straightforward. He wants to possess her and influence her and make her do whatever he wants. Look at the words he uses, ‘oblation.’

Oblation in a Christian mass refers to the Eucharist. the offering of Bread to be transmuted into the body of Christ, who sacrificed himself for the salvation of humankind. Such is the high altar of sacrifice on which St. John wishes to place Jane, as a woman to be sacrificed!

Actually, St. John is bullying her – he is blackmailing her, pushing her into a corner, said Arundhaty. He has the full conviction of a bigot about what he is doing, said Geetha. He is not trying to figure out whether she really wants such a vocation. Women exist only to suit the purposes of men.

In the home he has managed to mould her to his wishes, for example, she is laboriously helping him to study Hindustani in a very old-fashioned way. In his zeal he manages to convert her to the notion that she will find her true vocation as his, quote, ‘helpmeet.’ “Come as my helpmeet and fellow-labourer,” he says.

He wants her to propagate the gospel as St. Paul did in Asia Minor. She is quite religious and agrees.

But she stood up for herself in the end, said Geetha refusing to be a mere appendage of St. John’s work.

In fact, when she was reading this part, she was praying that Jane would not agree (said Arundhaty), that she would not fall for this move. Arundhaty was quite worried that Jane will actually fall for the ruse. That's the suspense.

What gives Jane pause is the perception that this marriage will have no love in it, said Joe. There would be no genuine attachment from St. John’s side. Because for him she is only a practical support for his work. He does not see her intrinsically as a person worthy to be loved, and cherished for her own sake.

That's what you need in a marriage, affirmed Geetha.

Geetha’s passage is a sort of relief after the heavy handedness of St. John Rivers, the dedicated missionary.

His sisters are so genuine and objective. Charlotte Brontë has portrayed women in a better light than men. Geetha read the portion where Jane comes to a place called Whitcross. She has run away from Mr Rochester and forgotten her purse in the coach, and she doesn't have any money. She's reached the point of starvation.

Jane flees Thornfield, she nearly starves to death

But readers will recall before she flees she speaks these heartfelt words to Rochester:

'All my heart is yours, sir: it belongs to you; and with you it would remain, were fate to exile the rest of me from your presence forever.'

She's begging for food from strangers now and at one point, a girl is going to throw away some stale porridge to the pig and she begs to eat that. She's exposed in the open and it starts raining. In desperation, she lays aside all her pride. She’s so hungry, not having eaten for days. Nothing is going to stop her from begging and she will do anything it takes to survive.

She notices a small fire burning somewhere, and the word that is used here is the same one that came in Zakia's reading, Ignis Fatuus, a false fire, that occurs when organic rotting matter catches fire spontaneously from the methane emitted.

She thought maybe it's just that and it will die out, but then she sees it again and she is drawn towards it. She sees a small house and the low window is just one foot from the ground. It is lit by a small lamp burning in a window .

She moves towards that light and imagines it is going to save her life. She would have died there otherwise. It was almost by supernatural intervention she found that little flicker of hope in her desperate situation.

Hence Geetha chose to read what was to be a turning point in Jane’s fortunes. The Rivers sisters were very supportive. Geetha thought Jane was so good, even though in her heart of hearts she hoped that St. John would marry her. She also hoped that the brother would stay in England.

In this passage you see the use of the word ‘conjured:’

“she earnestly conjured me to give up all thoughts of going out with her brother.” Conjure here means to solemnly entreat somebody – it may not be the first word we think of, but it is precise in this situation.

The women in this conversation have all the clarity, and this man, St. John, is in a world of his own. He thinks only of finding labour for his missionary work. He is thinking of his own calling, not thinking of her at all. He thinks that she will be very useful, ‘a useful tool’ is what she says.

Nowadays we take on staff in Kerala, and consider how employable they are. Can she cook well? It shows up in so many unions of marriage. There are couples where the wives are just useful tools.

Joe reminded readers that in this passage that Geetha just read, Calcutta is mentioned as being a place to be ‘grilled alive.’ It is true that a lot of young people perished there, among them women who came out from England seeking marriage to English officers in Calcutta.

Rose Aylmer is mentioned in Vikram Seth’s great novel, A Suitable Boy. One of the suitors of Lata in that novel is Amit Chatterji, who is also a poet. He bonds with Lata over their shared love of literature and in one scene takes her to see the old Park Street Cemetery and shows her the monument to Rose Aylmer, a young girl aged 20, who died of cholera. She came out to India to visit her aunt, Lady Russell, wife of one of the Judges of the High Court at Calcutta. This frail young lady did not long survive the climate; hence Calcutta was indeed a ‘hell-hole’ for her.

Amit Chaterji recites the lines by Walter Savage Landor inscribed on the monument – Rose was only 17 when, in 1797, she happened to meet the poet Walter Savage Landor, then 22, in Wales. Together they would take long walks on the hills.

Rose Aylmer's grave monument in the Old Park Street Cemetery

Ah what avails the sceptred race,

Ah what the form divine!

What every virtue, every grace!

Rose Aylmer, all were thine.

Rose Aylmer, whom these wakeful eyes

May weep, but never see,

A night of memories and of sighs

I consecrate to thee.

Can you visualise the second stanza as a ghazal couplet? Go for it, readers! This is your DRE (Diligent Reader Exercise).

Priya read her passage from Ch 35 where after a talk with St. John Rivers Jane is almost convinced to marry him; but then she hears a mysterious voice calling out to her in the dark, and she replies.

This is the Eureka moment where she very clearly decides that she should not accede to St. John's proposal. She hears a mysterious voice calling out to her. Was it Mr. Rochester? This is a sacral moment for her. The voice calling out from the hills beyond Marsh Glen has the element they label as Gothic.

Jane hears a voice crying out “Jane! Jane! Jane!”

Mr Rochester too, far away in Ferndean Manor, a secluded house in the woods, hears her voice calling out at the same time. He is blind now from the fire.

As the winds brought his voice to Jane it was very dramatic, very intense. You have to read Jane’s evocative words:

the room was full of moonlight. My heart beat fast and thick: I heard its throb. Suddenly it stood still to an inexpressible feeling that thrilled it through, and passed at once to my head and extremities. The feeling was not like an electric shock, but it was quite as sharp, as strange, as startling: it acted on my senses as if their utmost activity hitherto had been but torpor, from which they were now summoned and forced to wake. They rose expectant: eye and ear waited while the flesh quivered on my bones.

The imagery is so vivid you could almost be there. The whole book has that thrill of an intimacy conveyed by language where you can feel yourself inside the mind of Jane.

Readers thanked Zakia and Shoba for choosing this novel. Shoba had not read it properly till now; it was Zakia's choice. Shoba’s mother and aunts used to keep talking about this book as Shoba listened. Devika confirmed having heard her mother talk about Jane Eyre too. About many other older authors too, some of whom one can't find in print nowadays.

It's a lovely book, averred Priya. Devika told Saras once about this author called Marie Corelli, whose real name was Mary Mackay, a popular British novelist known for her melodramatic and often controversial works during the Victorian and Edwardian eras. She achieved immense success despite being piled on by literary critics, and her novels were widely read by a broad audience, which included Queen Victoria..

Devika’s mother used to rave about Ms Corelli. Devika remembers years ago, finding it in a library in Chennai, in Anna Nagar, a tiny library which she frequented. Thus she too derived a taste for Ms Corelli’s books. But lately she hasn’t seen books of Ms Corelli in bookstores. However, consult:

Has anyone heard of her? She was educated by nuns. See her wiki:

Joe asked, why is Jane Eyre universally popular among women?

Because it's love story, Joe, all the women readers chimed in.

Arundhaty vouchsafed it is not just a love story, but features a woman who has to struggle in a world dominated by men. Her internal struggles are much like what women experience anywhere and a lot of women connect with that.

The struggle for independence resonates with all women. At some stage of their lives women struggle to find their independent voice. They are unable to really speak out because they face consequences. They want to say what they want to say. Jane being so expressive holds up an example to other women.

Some women by their good fortune do have the liberty to say what they want. The ones who have it are lucky. Most women labour under some disadvantage in speaking out

Jane is a strong character. The people who relate to her are strong themselves or are aspiring to be strong, said Arundhaty.

These are the 1800s, and women had no exemplars.

Joe asked Saras what she thought was the appeal of this novel to women in particular?

Saras confessed she didn't know. She felt the love story is the main thing that stimulates everybody; it is that romance with heartbreaks that makes it so popular as a novel among women.

Saras knows Jane is a strong woman, who goes against the grain of society in those times where women willingly accepted subordination to men. But ultimately, she thought it was the love story that captivated everybody. The love story and a happy ending, at last, said Priya.

It was not actually a happy ending because of what happened to Mr. Rochester, being blinded and having one hand crippled. Shoba thought in a way justice was served because of Rochester’s culpability in having proposed to Jane when he already had a wife.

His vision is coming back, Priya and Devika joyfully retorted. You have to be positive and see that he's back and improving.

Saras told Devika the Marie Corelli books are available on Project Gutenberg freely, their copyright having expired. Devika uses Project Gutenberg quite a bit.

Sadly, these women writers all died young. Everybody used to die young in olden days, said KumKum. Vaccination and other protections were still in the future. People used to die of smallpox, typhoid, cholera, TB, and a host of diseases that are preventable now.

There was some talk that the Brontë brother was ghost-writing the books of the Brontë sisters. There’s no substance to that; the sisters collaborated on early literary ventures, and each sister published novels under their own pseudonyms, and there is no evidence to suggest that Branwell Brontë authored any of their works.

The controversy was stoked because the brother was a writer, but he hardly went out of the drawing room of their house. Charlotte’s eyesight wasn't very good. She and her sister Emily were in Belgium for a while. The Brontë sisters’ poems were first published together in a volume titled Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell in 1846. This collection marked the sisters' initial foray into publishing, and they used pseudonyms to conceal their identities, with Charlotte using Currer Bell, Emily using Ellis Bell, and Anne using Acton Bell.

Charlotte and Emily spent some time in Brussels.

The only example in this book of a poem is what some call Rochester’s Song because he is singing as he plays the piano. It begins:

The truest love that ever heart

Felt at its kindled core,

Did through each vein, in quickened start,

The tide of being pour.

And ends thus:

My love has sworn, with sealing kiss,

With me to live—to die;

I have at last my nameless bliss.

As I love—loved am I!

It's all very regular, in 8-6-8-6 meter, the so-called hymn meter in which Emily Dickinson also wrote a lot of her poetry. These are quite forgettable lines of sentimental poetry.

Charlotte was not a poet actually – it was her sister Emily who really warmed to the poetic Muse. Twenty-one of her poems are in the jointly published volume of the Brontë sisters.

A lot of authors use poetry within their novels. If you look through Vikram Seth's A Suitable Boy, you will see the whole novel is punctuated by verse. Those are not negligible parts of the novel, and serve to bring out the different cultural and language strands that Vikram Seth sketches in that epic novel from Saeeda Bai’s ghazals that are in the vein of Ghalib, to Amit Chatterji’s more witty but rootless poems, bespeaking a poet torn from his Bengali roots..

Although Joe started with reservations he enjoyed this genre of writing – perhaps it is the best of its kind. Joe has his Spark Notes version of the novel, KumKum said. Joe knows that women didn't have opportunities and so on, but was the remedy for Charlotte Brontë to write this kind of turgid Latinate dialogue? Someone remarked, “Well, she wrote the book and even now we women love it.”

Saras added: “Yes, that is the thing. It is women who are reading it. It is relatable and it's a love story with a happy ending.”

The video that Joe sent to readers ahead of the session was by Benjamin McEvoy; it is a very good introduction without spoilers:

Benjamin McEvoy (https://benjaminmcevoy.com/) tells us How to Read Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë, and says the novel is “one of the most riveting love stories ever penned in English Literature.”

Our next book is Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin. And then we have Hound of the Baskervilles by Arthur Conan Doyle.

Giovanni's Room is a beautiful book. Priya has read Baldwin’s poems.

But it is not read in India, said KumKum. Thanking everybody, KumKum said it was a lovely session. Saras said she will tell us about Mr. Rochester's first wife.

Kavita

Kavita was so committed she read from the hospital even as her father was being discharged.

This short video is the final scene of Jane Eyre:

Blind Rochester places his hands over Jane's as they reunite

It is the last chapter, 36, after Jane meets with Mr. Rochester and he is reconciled to her. It’s a perfect romantic ending, a very tender passage:

I led him out of the wet and wild wood into some cheerful fields: I described to him how brilliantly green they were; how the flowers and hedges looked refreshed; how sparklingly blue was the sky. I sought a seat for him in a hidden and lovely spot, a dry stump of a tree; nor did I refuse to let him, when seated, place me on his knee.

Rochester and Jane are reconciled

=+=

Diligent Reader Exercise (DR) for Jane Eyre

There was a challenge in the body of the post to construct ghazal couplets for the second stanza of the Rose Aylmer poem by Landor:

Rose Aylmer, whom these wakeful eyes

May weep, but never see,

A night of memories and of sighs

I consecrate to thee.

– in whatever language was most malleable in the hands of the readers. People have written ghazal couplets in ALL the major Indian languages and in scores of foreign languages as well.

Readers responded for the most part by choosing scenes from Jane Eyre to translate the sentiments there expressed into verse in another language. Here below we list them in order of their submission:

1. Joe (in Hindi)

Translating the second stanza of Landor’s tribute to Rose Aylmer into Hindi:

रोज़ ऐल्मर, जिसे नहीं देख सकती

मेरी जागती आँखें, लेकिन रो सकती ,

यादों और आहों की एक रात

पेश करता हूँ तेरे साथ

Rose Aylmer, whom these wakeful eyes

May weep, but never see,

A night of memories and of sighs

May weep, but never see,

A night of memories and of sighs

I consecrate to thee

2. Priya (in Hindi)

When Jane decides not to marry St. John Rivers:

ये सनआटा, ये कैसी तनहाई

क्या कह रही हैं ?

ये ठंडी हवाये, ये काले बदरा

कुछ तो कह रहे हैं

ये उतावला मन, ये मचलता दिल

कुछ तो बोल रहा हैं

इस काले घोर अँधेरे में, इक हवा का झोका

कह रहा हैं, कह रहा है

जेन, जेन, जेन, जेन

Translation:

This sunshine, this kind of loneliness

What is it saying?

These cold winds, these dark clouds,

Are saying something.

This impatient mind, this restless heart,

Is saying something.

In this pitch black darkness, a gust of wind

Is saying, is saying:

Jane! Jane! Jane! Jane!

3. Priya (in Bhojpuri language of Bihar)

One in Bhojpuri

तू हमरा छोड़ कर गैलू कहाँ

कमाई धमाई ला

मूड कर देखु जरा

हमर क्या हाल बा

Translation:

Where did you go, leaving me?

Give me my right,

Turn and see

What is my plight.

4. Arundhaty (in Bangla)

What Jane says when she leaves Rochester:

আমার না আছে বাড়ি

না আছে ঘর

শুধু আছে আমার

এই বুকের ধর ধর

কেন টানছো আমায়

এই মিথ্যার জালে

কোথায় পালাবো

আমি এই অন্ধকারে

চারিদিকে কেউ নেই

কে দেবে আশ্রয়

ধিরে ধিরে মনবল

যায় যে ফুরাযে

Translation:

I don't have a home,

I don't have a room,

I only have this throbbing

In my chest.

Why are you dragging me

Into this web of lies,

Where can I escape,

From this darkness,

There's no one around,

Who can give me shelter,

Slowly my mental strength

Is fading away.

5. Devika (in Hindi)

Chosen from the passage I'd read for our session.

मै उसे इतना प्यार करती हूँ

फिर भी वो मुझे देखता भी नहीं !

घंटो मै उसके साथ बैठी हूँ

मगर उसकी ध्यान किसी और पे रहती!!

Translation:

I love him so much

yet he doesn't even look at me!

I sit with him for hours

but his attention is on someone else!!

6. Geetha (in Manglish – Malayalam rendered in English transliteration)

Ende ullu nurungunnu,

ningalodulla sneham ennil

niranju thulumbunnu.

Ennalum thettum sariyum en

Munbaake thelinju nikkumbol,

Ini oru nimisham polum

Ivide nikkaan enikku pattilla.

Njaan vida parayunnu

en hridayame

Ningal nannay varatte.

My heart is torn into shreds.

Love for you overflows my being.

But right and wrong stares at me with clarity.

I cannot stay a minute more in this place.

I bid you goodbye my heart.

May you fare well.

7. Shoba (In French) who says it’s inspired by a song

Notre vieille Terre est une étoile

Où toi aussi tu brilles un peu

Je viens te chanter la ballade

La ballade d’une fille unique

Elle n’avait pas de titre ni grade (oh non!)

Orpheline, sans beauté sans argent

Elle devrait faire son propre chemin, un chemin rocheux

Qui menait à Rochestre.

Elle s’est trouvé follement amoureuse

Mais le destin, le destin cruel

N’a pas permis leur union.

Coeur brisé, elle s’est enfuie

Chez St John elle a trouvé l’abri.

Mais le faible cri de Rochestre

La ferait revenir, peut-être.

Translation:

Our old Earth is a star

Where you too shine a little

I come to sing you the ballad

The ballad of an only daughter

She had no title or rank (oh no!)

Orphaned, without beauty, without money

She should have made her own way, a rocky path

That led to Rochestre.

She found herself madly in love

But fate, cruel fate

Did not allow their union.

Brokenhearted, she ran away,

At St. John's she found shelter.

But Rochester’s faint cry

Would bring her back, perhaps.

8. KumKum (in Bangla)

She takes the quotation from Ch 33 where Jane spurns Rochester’s portrayal of her as a captive bird before she departs:

“I am no bird, and no net ensnares me; I am a free human being with an independent will, which I now exert to leave you.”

Here is KumKum’s verse, followed by a line-by-line translation.

জালে ধরার প্রশ্নই ওঠেনা,

আমি তো পাখী নই।

আমি স্বাধীন মানুষ,

বেঁচে আছি নিজস্ব মতে।

তোমাকে যে ছেড়ে যাচ্ছি,

আমারই সিদ্ধান্তে।

There is no question of capturing me in a net –

I am not a bird:

I am a free human being,

I live conforming to my own free will.

That I am leaving you

Derives from my sole wish.

9. Joe (English, Sanskrit translation and transliteration)

Taking off on the theme of woman’s independence demonstrated by Jane in the later chapters.

No woman am I

To be imprisoned by

My selfish master

Mister Rochester

I am the mistress of my will

Who does what she will

Am independent

Not your attendant

I flee your affection

Forsake your protection

Pursue my future

Follow adventure

Without your censure

Or your strictures

At my pleasure

Sans ligature

I’ll live as a creature

In wonder of Nature!

Om Shantih!

Sanskrit:

अहं नारी नास्मि

द्वारा कारावासः करणीयः

मम स्वार्थी स्वामी

श्रीमन रोचेस्टर

अहं मम इच्छायाः स्वामिनी अस्मि

सा यत् इच्छति तत् कः करोति

स्वतन्त्रः अस्मि

न तव परिचारकः

अहं तव स्नेहात् पलाययामि

रक्षणं त्यजतु

मम भविष्यस्य अनुसरणं कुरुत

साहसिकं अनुसरणं कुर्वन्तु

भवतः निन्दां विना

अथवा भवतः स्ट्रक्चर्स्

मम प्रसन्नतायां

विना किमपि बन्धनम्

अहं प्राणी इव जीविष्यामि

प्रकृतेः आश्चर्येन !

ॐ शान्तिः !

Transliteration:

aham nari nasmi

dvara karavasah karaniyah

mam svarthi svaami

sriman rochestar

aham mam ichayah svaamini asmi

saa yat ichati tat kah karoti

svatantrah asmi

na tav paricharakah

aham tav snehat palayayami

rakshanam tyajatu

mam bhavishyasya anusaranam kurut

sahasikam anusaranam kurvantu

bhavatah nindam vina

bhavatah bhartsana va

mam prasannatayam

bina kimapi bandhanam

aham prani iv jivishyami

prakruteh aashcharyen !

Om Shantih

=+=

The Sanskrit language has always appealed to Joe (though he does not understand it) for the decided gravitas of its utterance. One couplet in particular impressed him for the finality with which it conveyed an iron will:

अहं मम इच्छायाः स्वामिनी अस्मि

सा यत् इच्छति तत् कः करोति

aham mam ichayah svaamini asmi

saa yat ichati tat kah karoti

I am the mistress of my will

Who does what she will

You will feel the unbending firmness of the words –

saa yat ichati, tat kah karoti

10. Joe (English, Spanish)

Rose Aylmer, whom these wakeful eyes

May weep, but never see,

A night of memories and of sighs

I consecrate to thee.

Rosa Aylmer, a quien estos ojos despiertos

pueden llorar, pero nunca ver,

una noche de recuerdos y de suspiros

Yo te consagro para devolver.

The Readings

Saras Ch 2 Jane Eyre is locked up in the Red Room as punishment for defending herself against her cousin John Reed's bullying

This idea, consolatory in theory, I felt would be terrible if realised: with all my might I endeavoured to stifle it—I endeavoured to be firm. Shaking my hair from my eyes, I lifted my head and tried to look boldly round the dark room; at this moment a light gleamed on the wall. Was it, I asked myself, a ray from the moon penetrating some aperture in the blind? No; moonlight was still, and this stirred; while I gazed, it glided up to the ceiling and quivered over my head. I can now conjecture readily that this streak of light was, in all likelihood, a gleam from a lantern carried by some one across the lawn: but then, prepared as my mind was for horror, shaken as my nerves were by agitation, I thought the swift darting beam was a herald of some coming vision from another world. My heart beat thick, my head grew hot; a sound filled my ears, which I deemed the rushing of wings; something seemed near me; I was oppressed, suffocated: endurance broke down; I rushed to the door and shook the lock in desperate effort. Steps came running along the outer passage; the key turned, Bessie and Abbot entered.

“Miss Eyre, are you ill?” said Bessie.

“What a dreadful noise! it went quite through me!” exclaimed Abbot.

“Take me out! Let me go into the nursery!” was my cry.

“What for? Are you hurt? Have you seen something?” again demanded Bessie.

“Oh! I saw a light, and I thought a ghost would come.” I had now got hold of Bessie’s hand, and she did not snatch it from me.

“She has screamed out on purpose,” declared Abbot, in some disgust. “And what a scream! If she had been in great pain one would have excused it, but she only wanted to bring us all here: I know her naughty tricks.”

“What is all this?” demanded another voice peremptorily; and Mrs. Reed came along the corridor, her cap flying wide, her gown rustling stormily. “Abbot and Bessie, I believe I gave orders that Jane Eyre should be left in the red-room till I came to her myself.”

“Miss Jane screamed so loud, ma’am,” pleaded Bessie.

“Let her go,” was the only answer. “Loose Bessie’s hand, child: you cannot succeed in getting out by these means, be assured. I abhor artifice, particularly in children; it is my duty to show you that tricks will not answer: you will now stay here an hour longer, and it is only on condition of perfect submission and stillness that I shall liberate you then.”

“O aunt! have pity! Forgive me! I cannot endure it—let me be punished some other way! I shall be killed if—”

“Silence! This violence is all most repulsive:” and so, no doubt, she felt it. I was a precocious actress in her eyes; she sincerely looked on me as a compound of virulent passions, mean spirit, and dangerous duplicity.

Bessie and Abbot having retreated, Mrs. Reed, impatient of my now frantic anguish and wild sobs, abruptly thrust me back and locked me in, without farther parley. I heard her sweeping away; and soon after she was gone, I suppose I had a species of fit: unconsciousness closed the scene. (544 words)

Arundhaty Ch 10 Jane Eyre, Jane advertises in the Herald because she is seeking a position as a governess after leaving Lowood School.

I was not free to resume the interrupted chain of my reflections till bedtime: even then a teacher who occupied the same room with me kept me from the subject to which I longed to recur, by a prolonged effusion of small talk. How I wished sleep would silence her. It seemed as if, could I but go back to the idea which had last entered my mind as I stood at the window, some inventive suggestion would rise for my relief.

Miss Gryce snored at last; she was a heavy Welshwoman, and till now her habitual nasal strains had never been regarded by me in any other light than as a nuisance; to-night I hailed the first deep notes with satisfaction; I was debarrassed of interruption; my half-effaced thought instantly revived.

“A new servitude! There is something in that,” I soliloquised (mentally, be it understood; I did not talk aloud). “I know there is, because it does not sound too sweet; it is not like such words as Liberty, Excitement, Enjoyment: delightful sounds truly; but no more than sounds for me; and so hollow and fleeting that it is mere waste of time to listen to them. But Servitude! That must be matter of fact. Any one may serve: I have served here eight years; now all I want is to serve elsewhere. Can I not get so much of my own will? Is not the thing feasible? Yes—yes—the end is not so difficult; if I had only a brain active enough to ferret out the means of attaining it.”

I sat up in bed by way of arousing this said brain: it was a chilly night; I covered my shoulders with a shawl, and then I proceeded to think again with all my might.

“What do I want? A new place, in a new house, amongst new faces, under new circumstances: I want this because it is of no use wanting anything better. How do people do to get a new place? They apply to friends, I suppose: I have no friends. There are many others who have no friends, who must look about for themselves and be their own helpers; and what is their resource?”

I could not tell: nothing answered me; I then ordered my brain to find a response, and quickly. It worked and worked faster: I felt the pulses throb in my head and temples; but for nearly an hour it worked in chaos; and no result came of its efforts. Feverish with vain labour, I got up and took a turn in the room; undrew the curtain, noted a star or two, shivered with cold, and again crept to bed.

A kind fairy, in my absence, had surely dropped the required suggestion on my pillow; for as I lay down, it came quietly and naturally to my mind:—“Those who want situations advertise; you must advertise in the ——shire Herald.”

“How? I know nothing about advertising.”

Replies rose smooth and prompt now:—

“You must enclose the advertisement and the money to pay for it under a cover directed to the editor of the Herald; you must put it, the first opportunity you have, into the post at Lowton; answers must be addressed to J.E., at the post-office there; you can go and inquire in about a week after you send your letter, if any are come, and act accordingly.”

This scheme I went over twice, thrice; it was then digested in my mind; I had it in a clear practical form: I felt satisfied, and fell asleep. (593 words)

Thomo Ch 12 Mr Rochester returning to Thornfield on his horse, comes a cropper and has to be helped home by young Jane.

No Gytrash was this,—only a traveller taking the short cut to Millcote. He passed, and I went on; a few steps, and I turned: a sliding sound and an exclamation of “What the deuce is to do now?” and a clattering tumble, arrested my attention. Man and horse were down; they had slipped on the sheet of ice which glazed the causeway. The dog came bounding back, and seeing his master in a predicament, and hearing the horse groan, barked till the evening hills echoed the sound, which was deep in proportion to his magnitude. He snuffed round the prostrate group, and then he ran up to me; it was all he could do,—there was no other help at hand to summon. I obeyed him, and walked down to the traveller, by this time struggling himself free of his steed. His efforts were so vigorous, I thought he could not be much hurt; but I asked him the question—

“Are you injured, sir?”

I think he was swearing, but am not certain; however, he was pronouncing some formula which prevented him from replying to me directly.

“Can I do anything?” I asked again.

“You must just stand on one side,” he answered as he rose, first to his knees, and then to his feet. I did; whereupon began a heaving, stamping, clattering process, accompanied by a barking and baying which removed me effectually some yards’ distance; but I would not be driven quite away till I saw the event. This was finally fortunate; the horse was re-established, and the dog was silenced with a “Down, Pilot!” The traveller now, stooping, felt his foot and leg, as if trying whether they were sound; apparently something ailed them, for he halted to the stile whence I had just risen, and sat down.

I was in the mood for being useful, or at least officious, I think, for I now drew near him again.

“If you are hurt, and want help, sir, I can fetch some one either from Thornfield Hall or from Hay.”

“Thank you: I shall do: I have no broken bones,—only a sprain;” and again he stood up and tried his foot, but the result extorted an involuntary “Ugh!”

Something of daylight still lingered, and the moon was waxing bright: I could see him plainly. His figure was enveloped in a riding cloak, fur collared and steel clasped; its details were not apparent, but I traced the general points of middle height and considerable breadth of chest.

…

If even this stranger had smiled and been good-humoured to me when I addressed him; if he had put off my offer of assistance gaily and with thanks, I should have gone on my way and not felt any vocation to renew inquiries: but the frown, the roughness of the traveller, set me at my ease: I retained my station when he waved to me to go, and announced—

“I cannot think of leaving you, sir, at so late an hour, in this solitary lane, till I see you are fit to mount your horse.”

He looked at me when I said this; he had hardly turned his eyes in my direction before.

“I should think you ought to be at home yourself,” said he, “if you have a home in this neighbourhood: where do you come from?” (556 words)

Zakia Ch 16 When Jane reflecting on her life at Thornfield Hall, disabuses herself of the notion that Mr Rochester could have a preference for her.

When once more alone, I reviewed the information I had got; looked into my heart, examined its thoughts and feelings, and endeavoured to bring back with a strict hand such as had been straying through imagination’s boundless and trackless waste, into the safe fold of common sense.

Arraigned at my own bar, Memory having given her evidence of the hopes, wishes, sentiments I had been cherishing since last night—of the general state of mind in which I had indulged for nearly a fortnight past; Reason having come forward and told, in her own quiet way, a plain, unvarnished tale, showing how I had rejected the real, and rabidly devoured the ideal;—I pronounced judgment to this effect:—

That a greater fool than Jane Eyre had never breathed the breath of life; that a more fantastic idiot had never surfeited herself on sweet lies, and swallowed poison as if it were nectar.

“You,” I said, “a favourite with Mr. Rochester? You gifted with the power of pleasing him? You of importance to him in any way? Go! your folly sickens me. And you have derived pleasure from occasional tokens of preference—equivocal tokens shown by a gentleman of family and a man of the world to a dependent and a novice. How dared you? Poor stupid dupe!—Could not even self-interest make you wiser? You repeated to yourself this morning the brief scene of last night?—Cover your face and be ashamed! He said something in praise of your eyes, did he? Blind puppy! Open their bleared lids and look on your own accursed senselessness! It does good to no woman to be flattered by her superior, who cannot possibly intend to marry her; and it is madness in all women to let a secret love kindle within them, which, if unreturned and unknown, must devour the life that feeds it; and, if discovered and responded to, must lead, ignis-fatuus-like, into miry wilds whence there is no extrication.

“Listen, then, Jane Eyre, to your sentence: to-morrow, place the glass before you, and draw in chalk your own picture, faithfully, without softening one defect; omit no harsh line, smooth away no displeasing irregularity; write under it, ‘Portrait of a Governess, disconnected, poor, and plain.’ (368 words)

Devika Ch 18 Although Jane is ignored by Mr Rochester who is wooing the beautiful Miss Ingram sedulously, Jane realises Ingram has defects that disqualify her