This

session was held in Thommo and Geetha’s home with wonderful snacks to leaven

the proceedings. As usual the potpourri of poets came from several parts of the

world: Lebanon, UK, India, Turkey, and Ireland.

Priya, & Esther

The

death of Seamus Heaney on Aug 30, 2013 prompted two readers to reach for his

verse. Limericks made a comeback once again, and some quite recent examples are

included.

Talitha

A

major upcoming anniversary is to be celebrated, Shakespeare’s 450th birth

anniversary on April 23, 2014, with recitations from his plays and sonnets, and

music from the songs.

KumKum, Talitha, Priya, & Esther

Here

we are at the end of the session:

Joe, Sunil, KumKum, Talitha, Esther, Priya, Thommo, Geetha

For

a fuller account click below.

Full account

and record of KRG Poetry session on Sep 19, 2013

Present:

Joe, KumKum, Talitha, Priya, Esther, Geetha, Thommo, Sunil

Missing:

Bobby

Absent:

Sivaram (on tirth), Kavita (not in

town), Zakia (in Bengaluru), Mathew (last minute emergency)

We

were meeting in Thommo’s place because the Library at the CYC was being used

during renovation elsewhere in the club. The wonderful result was Geetha served

us coffee and bondas with McVities

biscuits. We are glad to know that Geetha is no longer unnerved by the KRG

group, and she may join us even while continuing with her teaching at Choice School

for two more years.

We

decided to have a celebration of Shakespeare’s 450th birth anniversary (April

23, 2014). The last such celebration we had was in 2009 when Talitha organised ‘Shakescene’:

You

will recall the KRG Elizabethan Singers rendered three beautiful songs from

Shakespeare’s plays and a sonnet set to tune by Thommo. We need a keyboard

player; Esther volunteered and Joe said this talent makes her a precious member

of our group.

The

dates for the remaining sessions of the year are agreed as follows:

Fri Oct 11,

2013 Emma by Jane Austen

Fri Nov 8,

2013 Poetry

Thu Dec 12,

2013 The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar

Wilde

Our

next reading will be at the CYC and although Joe & KumKum will miss the Oct

and Nov sessions on account of their trip to USA, Joe promised to send sound

files as a stand-in for attendance, if Priya will play them on her computer to

the reading group. Priya agreed. She will be the convenor for the next two

sessions. Once Priya was asked by the Manager at CYC, it seems, what we all do

in the library when we meet. Do we read the library books? And why is the

discussion so animated? Should the Club provide curtains for the group to veil

their raucous rumblings?

Thommo

said he had been urging CYC for a long time to begin a library. At the Cochin

Club in Fort Kochi, the library was inaugurated by buying wholesale the library

of the Quilon Club (a planters’ club of Harrison’s Malayalam company) when that

closed down.

Joe,

KumKum, Mathew & Priya are following the online Modern Poetry course

offered free by Univ of Pennsylvania through Coursera:

Talitha

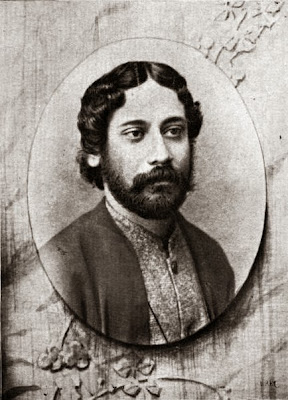

Lewis Carroll - the young Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832 – 1898)

Lewis

Carroll’s humorous verse from Through the Looking Glass was read by Talitha. It

is a great piece of mock-ironic humour with many famous lines such as this:

No

birds were flying overhead –

There were no birds to fly

(a

kind of post-Armageddon scene, said Talitha).

Perhaps

the most famous quote from here is:

"The

time has come," the Walrus said,

"To talk of many things:

Of

shoes--and ships--and sealing-wax--

Of cabbages--and kings--

And

why the sea is boiling hot--

And whether pigs have wings."

Joe

said this poem was a great favourite of his children who’d stay rapt when he

read it out to them at ages 5 and 6.

So

too the lines:

‘I

weep for you the Walrus said,

‘I deeply sympathise.’

With

sobs and tears he sorted out

Those of largest size,

Talitha

used a book by Derek O’Brien, Speak Up,

Speak Out : My Favourite Elocution Pieces and How to Deliver Them. This

elicited some information on his father Neill O’Brien, erstwhile chief of

Oxford University Press in India, and representative for Anglo Indians. He

taught English at St. Xavier’s College, College, when Joe was there. His mother

was a Bengali. Derek, his son, has a media company, Derek O’Brien Associates,

and was a one-time quizmaster on TV and is now Trinamul Congress MP.

Lewis

Carroll’s Home Page is here:

KumKum

Rabindranath Tagore (1861 – 1941)

Tagore

was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature on Sept 10, 1913, a hundred years

ago. He was the first Asian to get the prize. In an unusual gesture, this year,

the Swedish Govt, jointly with the Indian Govt celebrated the occasion through

various cultural events in both the countries.

KumKum

thought of presenting Tagore to KRG Readers once again, but this time as a

story teller in Verse. Tagore wrote many long poems which are actually one-act

plays with different characters saying their parts.

Some

of these he took from the Mahabharata, Ramayana, and Folk tales from different

parts of India; some were from religious texts, and some others were his

inventions.

The

one she read is titled Karna-Kunti Sangbad from Rabindranath's book Kahani.

It is a well-known story from the Mahabharata. A day before Karna was to

face Arjuna in the war, the worried mother, Kunti, meets Karna alone, and tries

to entice him away to the side of the Pandavas. She tells him the truth of his

birth and that she, Kunti, is his real mother. But, Karna remains steadfast.

The

poem in Bengali is one of Rabindranath's best in this genre. Ketaki Kushari

Dyson, poet, author, and an accomplished translator of Tagore's works, has done

a superb job in her translation of the poem, which Joe nevertheless has

tinkered with. These are excerpts of the poem taken from KKD’s book of

translations, i won't let you go:

Talitha

mentioned that Karna had been disadvantaged earlier in the Mahabharata in seeking the hand of Draupadi, on account of his

humble birth. But here he is revealed as being of noble lineage, unknown to

him. At the end of the war Kunti will have five sons, for either Arjuna or

Karna will die. Krishna played foul and disabled a weapon of Karna and he was

killed while attempting to lift his chariot out of a rut. Here from the

Wikipedia entry:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karna

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karna

“Karna

was the son of Surya (a solar deity) and Kunti. He was born to Kunti before her

marriage with Pandu. Karna was the closest friend of Duryodhana and fought on

his behalf against the Pandavas (his brothers) in the famous Kurukshetra war.

Karna fought against misfortune throughout his life and kept his word under all

circumstances. Many admire him for his courage and generosity. It is believed

that Karna founded the city of Karnal.

Many

believe that he was the greatest warrior of Mahabharata since he was only able

to be defeated by Arjuna along with a combination of 3 curses, Indra's efforts

and Kunti's request.”

Joe

wondered whether this English version from the Bengali of Rabindranath,

abridged by KumKum to shorten the long poem, could be considered a translation

of a translation, since the original story must have been in Sanskrit.

The

talk turned to the Gitanjali as a translation, which Talitha said was not done

by Rabindranath. A critique of that is here by Joe:

Tagore could not

resist the urge to simplify when he translated some of his poems into English.

The Gitanjali translation, which he made himself first and then got some help

from WB Yeats in redaction, is taken by modern critics as an example of the

disservice he did himself as a poet. To quote Fr Pierre Fallon (a Jesuit who

taught Comparative Literature in Jadavpur University when I was in college at

St Xavier's): “The Western Gitanjali loses much of the musical beauty and evocative

power of the original poems.” Yet he calls it a 'jewel' in the category of

English religious poetry.

Priya

said you can get many Bengali channels on TataSky dish network by paying Rs

35/- per month extra over the basic charge. Everyone lamented that WorldSpace radio

became defunct some years back. Another site, said Sunil, is the Internet radio

site TuneIn:

Joe

Seamus Heaney (1939-2013)

Seamus

Heaney has 12 collections from Death of a Naturalist (1966), to Human

Chain (2010), his last representing mostly ruminations on the end of life

after his stroke in 2006. He won many prizes: the Forward (2010), T.S. Eliot (

2006) for the collection District and

Circle, Whitbread (1996) for his translation of the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf, and the Nobel Prize for

Literature in 1995; "for works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth, which

exalt everyday miracles and the living past", in the words of the Nobel

citation.

He taught for a while at Harvard for several years

(one semester a year), and was at Oxford as Professor of Poetry, and Queen’s

College. Born in Northern Ireland, he was a Catholic and nationalist who chose

to live in the South. He once wrote this in protest when he was classified as

‘British’ poet in an anthology published in England:

Be advised, my passport's green

No glass of ours was ever raised

To toast the Queen.

No glass of ours was ever raised

To toast the Queen.

Born in farm country in N Ireland in Bellaghy in

Londonderry County, he was the eldest of many children, the clever one who got

a scholarship and made it to Queens University in Belfast (St. Columb’s

College). He never forgot his country origins and made great use of farm

imagery and rural situations in his poetry. In this respect he was like Ted

Hughes whom he greatly admired. He was a writer of great distinction on poetry

with published volumes of his lectures and in the volume of literary criticism Finders/Keepers his prose shows his wide

reading and great discernment.

One of his famous poems is the first one in his

first collection in 1966, called Digging.

After an admiring description of his father digging in the field, it ends:

But I've no spade to follow men like them.

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I'll dig with it.

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I'll dig with it.

He became a full-time poet and writer in 1972 and

gave up his teaching career when he realised he had found his unique voice in a

career as poet. One of the sad events of his boyhood was when a younger brother

was killed in an accident. He transformed this into a poem called Mid-term

Break.

He

was troubled by the sectarian violence in N Ireland, deploring the terrorism

and the need to take sides. He used his poetry to state the painful truth he

saw. Frank McGuinness, the Irish playwright, said: "During the darkest

days of the conflict he was our conscience: a conscience that was accurate and

precise in how it articulated what was happening.”

He

was a man greatly loved for his personal kindness and courtesy, and for his

encouragement of younger poets. He magically retrieved a love poem from his

stroke incident in 2006, when his wife, Marie, drove with him in the ambulance.

He confesses he was scared at being taken to hospital, grief-stricken at being

helpless, and a bit weepy. He suddenly felt a rush of love which came out in

the poem called Chanson d'Aventure:

There

are a couple of more poems Joe read.

Talitha

referred to pome Miracle where the

question is posed whether it is a religious poem or a secular one, since

Heaney, though raised a Catholic, ceased to observe the religion in worship.

The poem draws attention to the faith of the attendants who let down a

paralytic man through the roof into the presence of Jesus, seeking a cure. In a

similar vein is the story of the woman with an ‘issue of blood’ who is cured

when she touches the hem of the garment worn by Jesus.

Priya

Heaney

was the poet she too chose; he died recently on Aug 30 at the age of 74. The

first one, Blackberry-Picking, is a sensuous

description of the act of picking the berries and its transformation in the

hands of those who handle it and eat it. Blackberries can become erotic subjects

in the hands of a poet such as Heaney.

Bluebeard (palms sticky as

Bluebeard's) is the person of whom wives inquire about the fatal private

room in the house at their peril. Priya said Yeats died in 1939, when Heaney was

born. Talitha quipped that since Joe also was born in 1939 (as he confessed

earlier), ‘who knows on whom the mantle has fallen.’ KumKum noted that she

would have been fed up when Joe retired from his academic career, had he not shown

this other inclination toward literature and poetry.

The second poem Priya read was titled Requiem for the Croppies. Here’s an explanation:

The croppies were called such because they wore their hair

cropped—to oppose the foppish, long-hair favoured by the aristocracy of the

time. They did carry barley in their

pockets. And, on June 21, 1798 at Vinegar Hill, they were cornered and many

were slaughtered by artillery bombardment.

They made two futile attempts to break the British line. The British

buried the bodies in mass, shallow graves—but the seeds of rebellion were

sown—and bore fruit when the barley in their pockets came up–nourished by their

own bodies–and bore fruit again in, 1913, 1916, 1969 and beyond—whenever the

revolutionary spirit could not be killed.

Sunil

Nazim Hikmet (1902 – 1963)

The

poet chosen was Nazim Hikmet, born in Salonika in the days of the Ottoman

Empire (now Thessaloniki in Greece). You may read his biography at:

He

was the first modern Turkish poet, and grew up when Kemal Ataturk took charge

of Turkey. There is a movement to bring back his bones from Greece to Turkey

now. Thommo noted that in Turkish the normal Muslim names spelled with ‘a’ are

replaced by ‘e’. The conversation digressed to the Syrian civil war afoot, and

America’s itching to bomb and intervene. There is nothing so favoured as

instability in the Middle East by the big powers, all keen to have first

options on the oil wealth there.

Faces of Our Women

is a lovely poem celebrating women, and it won KumKum’s heart. Afterwards the

conversation turned to the recent controversy over a Miss America winner of

India extraction, whose dusky complexion came in for the usual Twitter abuse.

Everyone was disgusted at the continuing Indian ideals of beauty that value

fair skin. The stupid ads fronted by Shah Rukh Khan advertising ‘Fair and

Lovely’ cream for Rs 10/- was an example held up to ridicule. Think of the late

Smita Patil, think of Nandita Das.

Talitha

said although Malayalis are no less enamoured of fair-skinned women, Malayali

poets do not denigrate the woman called ‘karutha

penna,’ dark lady. Thommo mentioned his father having been so fair that

when he went to the Customs to take delivery of a foreign car (Plymouth Fury) imported

for the use of his white boss in Dunlop, he was saluted and addressed as the

white man.

Priya

said the complexion demanded in Bihar for brides is either ‘cream and peach’ or

‘milky white.’

The

first poem, Hiroshima Child, has been

translated well according to Talitha. Joe was reminded of the darkest poem in

Vikram Seth's The Collected Poems, on

p.169. It is about the fateful day on Aug 6, 1945 when Hiroshima was reduced to

vaporous rubble by an atom bomb. It is titled A Doctor’s Journal Entry for August 6, 1945. There is no way of

excerpting from this long 64-line poem in couplets, for it unfolds one

continuous scene of desolation. The doctor tries to cope, and realises, one by

one, the calamitous effects on him, and on the other citizens of that single

blinding flash. We are brought face to face with the horror and degradation

visited on people by nuclear explosions. Seth has researched and read the

eye-witness accounts of the atomic blast and captures them in all their stark

horror.

Esther

Jerry Pinto (1966 –

Her

choice was Jerry Pinto, the Goan writer who lives and works in Mumbai. He won

the Hindu Lit for Life prize last year for his book Em and the Big Hoom. It took a decade or more in the writing. You

can read his bio at:

He

has worked at many jobs in his life. An earlier book of his Helen, the H-Bomb on the cabaret artiste

Helen of Hindi movies won a prize for film books. Jerry Pinto calls himself a

poet first and has published two volumes of poetry. His mother was bipolar and

suffered the alternating mood swings that characterise the disease. The first

poem Esther read, Bedside, speaks of

the son nursing the mother. These lines are quite striking:

I

have survived to write these lines

To

turn you, baste you and marinate

Our

twinned lives into a poem.

The

son is devastated that he could not hold on to his mother the way he wanted. These

lines knell his lasting regret:

Mummy,

find it in you to forgive me

And

I will try to be bigger than my guilt

And

forgive myself.

Geetha

Kahlil Gibran (1883 – 1931)

She

chose Kahlil Gibran. Geetha found The

Song of the Rain a lovely poem with imagery:

I

emerge from the heard of the sea

Soar

with the breeze. When I see a field in

Need,

I descend and embrace the flowers and

The

trees in a million little ways.

This

year Thommo said there is a worry about the crop in Kerala on account of

continuous rain. In his 32 years residing here he cannot recall such a lashing

of rain, almost every day since June 1, 2013.

Joe

said Gibran had many women admirers for his poetry. His wiki entry notes, “Gibran

is the third best-selling poet of all time, behind Shakespeare and Lao-Tzu.” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kahlil_Gibran)

But

there is a suspicion his inspirational verse is a bit mushy, somebody said. His

verse has been read twice before at KRG once in 2008, and then again in 2011 by

Zakia:

Thommo

Edward Lear (1812 – 1888)

Thommo

indicated he was going to bring down the literary altitude of the reading group

by dealing in Limericks. Not at all, said Joe, who enjoys limericks and uses

them to twit friends and relatives, or sometimes to greet them. Here’s one of

his recent efforts:

There

was a gal from Madras

Who

was due to be put out to grass,

But

she said at seventy:

“Though

I’m much past twenty,

As

a woman I’m still bindaas.”

Indira

Outcalt recited this memorable one at a previous KRG reading:

Said

the Duchess of Alba to Goya:

'Paint

some pictures to hang in my foya!'

So

he painted her twice:

In

the nude, to look nice,

And

then in her clothes, to annoya.

See

the Full Record link from http://kochiread.blogspot.in/2008/10/indira-and-penny-in-conversation-kumkum.html

Joe

was startled to come across these two referenced paintings staring at each

other across a hall in The Prado museum in Madrid. See

A

recent limerick caused a flutter at BBC when Stephen Fry was livecast on TV and

recited this:

There

was a young chaplain from King's

Who

talked about God and such things;

But

his real desire

Was

a boy in the choir

With

a bottom like jelly on springs

Unfortunate

and regrettable, said BBC.

Limericks

are often bawdy and they form the staple exchange at men’s gatherings. Nobody

at KRG can baulk at this, at once bawdy and literary:

There

once was a poet called Donne

Who

said 'Piss off!' to the sunne:

The

sunne said 'Jack

Get

out of the sack,

The

girl that you’re with is a nun'

Lear began the craze with his nonsense verse in 1845. More about the history and the formal metre can be read at:

More references are here:

A Book of Nonsense by Edward Lear

Abscissa & Mantissa bring you Limericks!

Wordsworth Book of Limericks

Poems

Talitha

The Walrus and The Carpenter

(from Through the

Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There, 1872)

The sun was shining on the sea,

Shining with all his might:

He did his very best to make

The billows smooth and bright--

And this was odd, because it was

The middle of the night.

Shining with all his might:

He did his very best to make

The billows smooth and bright--

And this was odd, because it was

The middle of the night.

The moon was shining sulkily,

Because she thought the sun

Had got no business to be there

After the day was done--

"It's very rude of him," she said,

"To come and spoil the fun!"

Because she thought the sun

Had got no business to be there

After the day was done--

"It's very rude of him," she said,

"To come and spoil the fun!"

The sea was wet as wet could be,

The sands were dry as dry.

You could not see a cloud, because

No cloud was in the sky:

No birds were flying overhead--

There were no birds to fly.

The sands were dry as dry.

You could not see a cloud, because

No cloud was in the sky:

No birds were flying overhead--

There were no birds to fly.

The Walrus and the Carpenter

Were walking close at hand;

They wept like anything to see

Such quantities of sand:

"If this were only cleared away,"

They said, "it would be grand!"

Were walking close at hand;

They wept like anything to see

Such quantities of sand:

"If this were only cleared away,"

They said, "it would be grand!"

"If seven maids with seven mops

Swept it for half a year.

Do you suppose," the Walrus said,

"That they could get it clear?"

"I doubt it," said the Carpenter,

And shed a bitter tear.

Swept it for half a year.

Do you suppose," the Walrus said,

"That they could get it clear?"

"I doubt it," said the Carpenter,

And shed a bitter tear.

"O Oysters, come and walk with us!"

The Walrus did beseech.

"A pleasant walk, a pleasant talk,

Along the briny beach:

We cannot do with more than four,

To give a hand to each."

The Walrus did beseech.

"A pleasant walk, a pleasant talk,

Along the briny beach:

We cannot do with more than four,

To give a hand to each."

The eldest Oyster looked at him,

But never a word he said:

The eldest Oyster winked his eye,

And shook his heavy head--

Meaning to say he did not choose

To leave the oyster-bed.

But never a word he said:

The eldest Oyster winked his eye,

And shook his heavy head--

Meaning to say he did not choose

To leave the oyster-bed.

But four young Oysters hurried up,

All eager for the treat:

Their coats were brushed, their faces washed,

Their shoes were clean and neat--

And this was odd, because, you know,

They hadn't any feet.

All eager for the treat:

Their coats were brushed, their faces washed,

Their shoes were clean and neat--

And this was odd, because, you know,

They hadn't any feet.

Four other Oysters followed them,

And yet another four;

And thick and fast they came at last,

And more, and more, and more--

All hopping through the frothy waves,

And scrambling to the shore.

And yet another four;

And thick and fast they came at last,

And more, and more, and more--

All hopping through the frothy waves,

And scrambling to the shore.

The Walrus and the Carpenter

Walked on a mile or so,

And then they rested on a rock

Conveniently low:

And all the little Oysters stood

And waited in a row.

Walked on a mile or so,

And then they rested on a rock

Conveniently low:

And all the little Oysters stood

And waited in a row.

"The time has come," the Walrus said,

"To talk of many things:

Of shoes--and ships--and sealing-wax--

Of cabbages--and kings--

And why the sea is boiling hot--

And whether pigs have wings."

"To talk of many things:

Of shoes--and ships--and sealing-wax--

Of cabbages--and kings--

And why the sea is boiling hot--

And whether pigs have wings."

"But wait a bit," the Oysters cried,

"Before we have our chat;

For some of us are out of breath,

And all of us are fat!"

"No hurry!" said the Carpenter.

They thanked him much for that.

"Before we have our chat;

For some of us are out of breath,

And all of us are fat!"

"No hurry!" said the Carpenter.

They thanked him much for that.

"A loaf of bread," the Walrus said,

"Is what we chiefly need:

Pepper and vinegar besides

Are very good indeed--

Now if you're ready, Oysters dear,

We can begin to feed."

"Is what we chiefly need:

Pepper and vinegar besides

Are very good indeed--

Now if you're ready, Oysters dear,

We can begin to feed."

"But not on us!" the Oysters cried,

Turning a little blue.

"After such kindness, that would be

A dismal thing to do!"

"The night is fine," the Walrus said.

"Do you admire the view?

Turning a little blue.

"After such kindness, that would be

A dismal thing to do!"

"The night is fine," the Walrus said.

"Do you admire the view?

"It was so kind of you to come!

And you are very nice!"

The Carpenter said nothing but

"Cut us another slice:

I wish you were not quite so deaf--

I've had to ask you twice!"

And you are very nice!"

The Carpenter said nothing but

"Cut us another slice:

I wish you were not quite so deaf--

I've had to ask you twice!"

"It seems a shame," the Walrus said,

"To play them such a trick,

After we've brought them out so far,

And made them trot so quick!"

The Carpenter said nothing but

"The butter's spread too thick!"

"To play them such a trick,

After we've brought them out so far,

And made them trot so quick!"

The Carpenter said nothing but

"The butter's spread too thick!"

"I weep for you," the Walrus said:

"I deeply sympathize."

With sobs and tears he sorted out

Those of the largest size,

Holding his pocket-handkerchief

Before his streaming eyes.

"I deeply sympathize."

With sobs and tears he sorted out

Those of the largest size,

Holding his pocket-handkerchief

Before his streaming eyes.

"O Oysters," said the Carpenter,

"You've had a pleasant run!

Shall we be trotting home again?'

But answer came there none--

And this was scarcely odd, because

They'd eaten every one.

"You've had a pleasant run!

Shall we be trotting home again?'

But answer came there none--

And this was scarcely odd, because

They'd eaten every one.

KumKum

Excerpts

of the Dialogue between Karna and Kunti from Karna-Kunti Sangbad, a long poem from Rabindranath's book Kahani.

Karna. On sacred Jahnavi's shore I say my prayers

to the evening sun. Karna is my

name,

son of Adhirath the charioteer,

and Radha is my mother

That's who I am. Lady, who are

you?

Kunti. Child, in the first dawn of your life

it was I who launched you into

this world.

That's me, and today I've cast

aside

all embarrassment, to tell you

who I am.

Karna. Respected lady, the light of your lowered

eyes

melts my heart, as the sun's rays

melt

mountain snows. Your voice

pierces my ears as a voice from a

previous birth

and stirs strange pain. Tell me

then,

by what chain of mystery is my

birth linked

to you, unknown woman ?

Kunti. Oh, be patient,

child, for a moment! Let the

sun-god first

slide to his rest, and let

evening's darkness

thicken round us — now let me

tell you, warrior,

I am Kunti.

Karna. You are Kunti ! The mother of Arjun !

Kunti. Arjun's mother indeed! But son,

hate me not for that.

Karna. I salute you, noble lady. A royal mother you

are:

so why are you here alone? This

is a field of battle,

and I am the commander of the

Kaurava army.

Kunti. Son, I've come to beg a favour of you —

Don't turn me away empty-handed.

Karna. A favour? From me!

Barring my manhood, and what

dharma requires,

the rest will be at your feet.

Kunti. I have come to take you away.

Karna. And where will you take me?

Kunti. To my thirsty bosom — to cosset you.

Karna. A lucky woman you are, blessed with five

sons.

And I, just a petty princeling,

without pedigree —

where would you find room for me?

Kunti. Right at the top!

I would place you above all my

other sons,

for you are the eldest.

Karna. By what right

would I aspire to that state?

Tell me how

from those already cheated of

empire

I could possibly take a portion

of that wealth,

and a mother's love, which is

fully theirs.

A mother's heart cannot be bought

or procured by force. It's a

divine gift.

Kunti. O my son,

by divine right you are descended

of my womb — and by that same

right

return again, in glory; disregard

all —

take your own place amongst your

brothers,

in my maternal love.

Karna. Then why

did you consign me so

ingloriously —

without family honour, no

mother's eyes to watch me —

to the mercy of this blind,

unknown world? Why did you

let me float away on the current

of contempt

so irreversibly, banishing me

from my brothers?

You put a distance between Arjun

and me,

whence from childhood a subtle

divide

of bitter enmity distances us

and causes an irresistible

aversion —

Mother, have you no answer?

Kunti. Who knew, alas, that day

when I forsook a tiny, helpless

child,

that from somewhere he would gain

a hero's power,

return one day along a tortuous

path,

and with his own cruel hands hurl

weapons at those

born of the same mother!

What a curse this is!

Karna. Mother, don't be afraid.

I predict the Pandavas will win.

Let me stay with the losers,

whose hopes will be dashed.

The night of my birth you left me

upon the earth,

nameless, homeless. Likewise,

today

be ruthless, Mother, and just

abandon me:

leave me to my defeat, without fame

or hero's lustre.

Only this blessing give me before

you leave:

may greed for victory, for fame,

and for kingdom,

never deflect me from a warrior's

path to salvation.

(Rabindranath

wrote this on 26 February, 1900)

Joe

1. Mid-term Break:

I sat all morning in the college sick bay

Counting bells knelling classes to a close.

At two o'clock our neighbours drove me home.

I sat all morning in the college sick bay

Counting bells knelling classes to a close.

At two o'clock our neighbours drove me home.

In the porch I met my father crying--

He had always taken funerals in his stride--

And Big Jim Evans saying it was a hard blow.

He had always taken funerals in his stride--

And Big Jim Evans saying it was a hard blow.

The baby cooed and laughed and rocked the pram

When I came in, and I was embarrassed

By old men standing up to shake my hand

When I came in, and I was embarrassed

By old men standing up to shake my hand

And tell me they were 'sorry for my trouble,'

Whispers informed strangers I was the eldest,

Away at school, as my mother held my hand

Whispers informed strangers I was the eldest,

Away at school, as my mother held my hand

In hers and coughed out angry tearless sighs.

At ten o'clock the ambulance arrived

With the corpse, stanched and bandaged by the nurses.

At ten o'clock the ambulance arrived

With the corpse, stanched and bandaged by the nurses.

Next morning I went up into the room. Snowdrops

And candles soothed the bedside; I saw him

For the first time in six weeks. Paler now,

And candles soothed the bedside; I saw him

For the first time in six weeks. Paler now,

Wearing a poppy bruise on his left temple,

He lay in the four foot box as in his cot.

No gaudy scars, the bumper knocked him clear.

He lay in the four foot box as in his cot.

No gaudy scars, the bumper knocked him clear.

A four foot box, a foot for every year.

2. Chansond'Aventure

Love's mysteries in souls do grow

But yet the body is his book

I

Strapped on, wheeled out, forklifted, locked

In position for the drive,

Bone-shaken, bumped at speed,

Love's mysteries in souls do grow

But yet the body is his book

I

Strapped on, wheeled out, forklifted, locked

In position for the drive,

Bone-shaken, bumped at speed,

The nurse a passenger in front, you ensconced

In her vacated corner seat, me flat on my back--

Our postures all the journey still the same,

In her vacated corner seat, me flat on my back--

Our postures all the journey still the same,

Everything and nothing spoken,

Our eyebeams threaded laser-fast, no transport

Ever like it until then, in the sunlit cold

Our eyebeams threaded laser-fast, no transport

Ever like it until then, in the sunlit cold

Of a Sunday morning ambulance

When we might, O my love, have quoted Donne

On love on hold, body and soul apart.

When we might, O my love, have quoted Donne

On love on hold, body and soul apart.

II

Apart: the very word is like a bell

That the sexton Malachy Boyle outrolled

In illo tempore in Bellaghy

Apart: the very word is like a bell

That the sexton Malachy Boyle outrolled

In illo tempore in Bellaghy

Or the one I tolled in Derry in my turn

As college bellman, the haul of it there still

In the heel of my once capable

As college bellman, the haul of it there still

In the heel of my once capable

Warm hand, hand that I could not feel you lift

And lag in yours throughout that journey

When it lay flop-heavy as a bell-pull

And lag in yours throughout that journey

When it lay flop-heavy as a bell-pull

And we careered at speed through Dungloe,

Glendoan, our gaze ecstatic and bisected

By a hooked up drip-feed to the cannula.

Glendoan, our gaze ecstatic and bisected

By a hooked up drip-feed to the cannula.

III

The charioteer at Delphi holds his own,

His six horses and chariot gone,

His left hand lopped

The charioteer at Delphi holds his own,

His six horses and chariot gone,

His left hand lopped

From a wrist protruding like an open spout,

Bronze reins astream in his right, his gaze ahead

Empty as the space where the team should be,

Bronze reins astream in his right, his gaze ahead

Empty as the space where the team should be,

His eyes-front, straight-backed posture like my own

Doing physio in the corridor, holding up

As if once more I'd found myself in step

Doing physio in the corridor, holding up

As if once more I'd found myself in step

Between two shafts, another's hand on mine,

Each slither of the share, each stone it hit

Registered like a pulse in the timbered grips.

Each slither of the share, each stone it hit

Registered like a pulse in the timbered grips.

3. A Kite for Aibhín

After ‘L’Aquilone’ by Giovanni Pascoli (1855-1912)

Air from another life and time and place,

Pale blue heavenly air is supporting

A white wing beating high against the breeze,

Pale blue heavenly air is supporting

A white wing beating high against the breeze,

And yes, it is a kite! As when one afternoon

All of us there trooped out

Among the briar hedges and stripped thorn,

All of us there trooped out

Among the briar hedges and stripped thorn,

I take my stand again, halt opposite

Anahorish Hill to scan the blue,

Back in that field to launch our long-tailed comet.

Anahorish Hill to scan the blue,

Back in that field to launch our long-tailed comet.

And now it hovers, tugs, veers, dives askew,

Lifts itself, goes with the wind until

It rises to loud cheers from us below.

Lifts itself, goes with the wind until

It rises to loud cheers from us below.

Rises, and my hand is like a spindle

Unspooling, the kite a thin-stemmed flower

Climbing and carrying, carrying farther, higher

Unspooling, the kite a thin-stemmed flower

Climbing and carrying, carrying farther, higher

The longing in the breast and planted feet

And gazing face and heart of the kite flier

Until string breaks and—separate, elate—

And gazing face and heart of the kite flier

Until string breaks and—separate, elate—

The kite takes off, itself alone, a windfall.

4. Scaffolding

(a very confident poem from his first

book)

Masons, when they start upon a building,

Are careful to test out the scaffolding;

Are careful to test out the scaffolding;

Make sure that planks won’t slip at busy points,

Secure all ladders, tighten bolted joints.

Secure all ladders, tighten bolted joints.

And yet all this comes down when the job’s done

Showing off walls of sure and solid stone.

Showing off walls of sure and solid stone.

So if, my dear, there sometimes seem to be

Old bridges breaking between you and me

Old bridges breaking between you and me

Never fear. We may let the scaffolds fall

Confident that we have built our wall.

Confident that we have built our wall.

5. Miracle

Not the one who takes up his bed and walks

But the ones who have known him all along

And carry him in –

Not the one who takes up his bed and walks

But the ones who have known him all along

And carry him in –

Their shoulders numb,

the ache and stoop deeplocked

In their backs, the stretcher handles

Slippery with sweat. And no let‐up

In their backs, the stretcher handles

Slippery with sweat. And no let‐up

Until he’s strapped

on tight, made tiltable

And raised to the tiled roof, then lowered for healing.

Be mindful of them as they stand and wait

And raised to the tiled roof, then lowered for healing.

Be mindful of them as they stand and wait

For the burn of the

paid‐out ropes to cool,

Their slight lightheadedness and incredulity

To pass, those ones who had known him all along.

Their slight lightheadedness and incredulity

To pass, those ones who had known him all along.

[Written

after his heart attack in 2006, from which he took a year to recover; Heaney is

not a religious person. ‘Miracle’ uses the Biblical story of Jesus healing the

paralysed man (Mark 2, 1‐12) to refer to the poet’s own recovery from a stroke.

Is this a religious or a secular poem?]

Priya

Blackberry-Picking

Late August, given heavy rain and sun

For a full week, the blackberries would ripen.

At first, just one, a glossy purple clot

Among others, red, green, hard as a knot.

You ate that first one and its flesh was sweet

Like thickened wine: summer's blood was in it

Leaving stains upon the tongue and lust for

Picking. Then red ones inked up and that hunger

Sent us out with milk cans, pea tins, jam-pots

Where briars scratched and wet grass bleached our boots.

Round hayfields, cornfields and potato-drills

We trekked and picked until the cans were full

Until the tinkling bottom had been covered

With green ones, and on top big dark blobs burned

Like a plate of eyes. Our hands were peppered

With thorn pricks, our palms sticky as Bluebeard's.

We hoarded the fresh berries in the byre.

But when the bath was filled we found a fur,

A rat-grey fungus, glutting on our cache.

The juice was stinking too. Once off the bush

The fruit fermented, the sweet flesh would turn sour.

I always felt like crying. It wasn't fair

That all the lovely canfuls smelt of rot.

Each year I hoped they'd keep, knew they would not.

Requiem for the

Croppies

The pockets of our greatcoats full of barley...

No kitchens on the run, no striking camp...

We moved quick and sudden in our own country.

The priest lay behind ditches with the tramp.

A people hardly marching... on the hike...

We found new tactics happening each day:

We'd cut through reins and rider with the pike

And stampede cattle into infantry,

Then retreat through hedges where cavalry must be thrown.

Until... on Vinegar Hill... the final conclave.

Terraced thousands died, shaking scythes at cannon.

The hillside blushed, soaked in our broken wave.

They buried us without shroud or coffin

And in August... the barley grew up out of our grave.

Death Of A Naturalist

All

year the flax-dam festered in the heart

Of

the townland; green and heavy headed

Flax

had rotted there, weighted down by huge sods.

Daily

it sweltered in the punishing sun.

Bubbles

gargled delicately, bluebottles

Wove

a strong gauze of sound around the smell.

There

were dragon-flies, spotted butterflies,

But

best of all was the warm thick slobber

Of

frogspawn that grew like clotted water

In

the shade of the banks. Here, every spring

I

would fill jampotfuls of the jellied

Specks

to range on window-sills at home,

On

shelves at school, and wait and watch until

The

fattening dots burst into nimble-

Swimming

tadpoles. Miss Walls would tell us how

The

daddy frog was called a bullfrog

And

how he croaked and how the mammy frog

Laid

hundreds of little eggs and this was

Frogspawn.

You could tell the weather by frogs too

For

they were yellow in the sun and brown

In

rain.

Then

one hot day when fields were rank

With

cowdung in the grass the angry frogs

Invaded

the flax-dam; I ducked through hedges

To

a coarse croaking that I had not heard

Before.

The air was thick with a bass chorus.

Right

down the dam gross-bellied frogs were cocked

On

sods; their loose necks pulsed like sails. Some hopped:

The

slap and plop were obscene threats. Some sat

Poised

like mud grenades, their blunt heads farting.

I

sickened, turned, and ran. The great slime kings

Were

gathered there for vengeance and I knew

That

if I dipped my hand the spawn would clutch it.

Sunil poems by Nazim Hikmet (1902-1963, Turkey)

Hiroshima Child

I come and stand at every door

But none can hear my silent tread

I knock and yet remain unseen

For I am dead for I am dead

I'm only seven though I died

In Hiroshima long ago

I'm seven now as I was then

When children die they do not grow

My hair was scorched by swirling flame

My eyes grew dim my eyes grew blind

Death came and turned my bones to dust

And that was scattered by the wind

I need no fruit I need no rice

I need no sweets nor even bread

I ask for nothing for myself

For I am dead for I am dead

All that I need is that for peace

You fight today you fight today

So that the children of this world

Can live and grow and laugh and play

The Faces Of Our

Women

Mary didn't give birth to God.

Mary isn't the mother of God.

Mary is one mother among many mothers.

Mary gave birth to a son,

a son among many sons.

That's why Mary is so beautiful in all the pictures of her.

That's why Mary's son is so close to us, like our own sons.

The faces of our women are the book of our pains.

Our pains, our faults and the blood we shed

carve scars on the faces of our women like plows.

And our joys are reflected in the eyes of women

like the dawns glowing on the lakes.

Our imaginations are on the faces of women we love.

Whether we see them or not, they are before us,

closest to our realities and furthest.

Esther

Bedside

I

watch your face hanging open

Your

warm wet mouth, your tongue flickering

Your

spectacles grimy, your hair alive

Your

forehead broad and wasted

Your

cheeks alternately limp and bulging.

I

do not need to watch your body

I

have tended it often

Eased

its pains with capsicum plasters

And

prayed I was easing your mind too

With

my litany fresh off the shelf:

Tegretol,

Anxol, Espazine, Hexidol

Neurobion,

Arrovit, Shelcal, Diazepam.

I

cross your palm with powder

And

pray, entire rosaries and masses,

satsangs

and majlises, that you should not

Tell

my future.

When

I last lifted you off the floor

You

were sitting close to my bed.

You

did not expect to fall

Not

under the knowing eyes of

Mother

of Perpetual Succour.

I

direct your gaze to the falling slipper

Of

the child in her arms.

It

falls, you told me some lives ago

Out

of fear of the foretold future

I

understand that slippage

But

you? You live it.

Some

nights you let me sleep in patches

I

have grown used to it, relying on my

Ability

to turn you off, and your pain.

I

have survived to write these lines

To

turn you, baste you and marinate

Our

twinned lives into a poem.

But

I wish I could keep

My

heart unguilty, my love fresh

My

thoughts wide-ranging, my eyes new

and

that wound — inflicted on days of empathy —

raw

and open.

What

happened to the in-betweens?

The

Erle Stanley Gardners and the Agathas?

The

monotonous card games and the inedible food?

The

forced Vicks-ings and the rage of Tiger balm?

Did

we take them away

With

our conscientious powder formulae?

There

are many options I know

The

glaze of stillness and the panacea of

forgetfulness

Or

the black snot that stained granny’s kerchief

A

trust in the occult, born of grief.

A

faith in God, born of habit.

So

many options and I, on auto-pilot

Cross

your palm with powder.

Outside,

I turn my face to the sun

Laugh,

play, pun, work, entertain, function.

I

know from a few grim examples

And

one bright shining one

How

the world fetes facades.

I

have grown used to seeing the one I devised

Reflected

in your laughter-silted eyes.

Inside,

I shrink from metaphor and magic

I

have no beliefs here, only a watchfulness.

My

world condenses into an ink-stain

As

your voice trails after me from room to room.

I

made promises for you, standing in the toilet

By

the skull of the Cyclops that drank my piss

I

broke those promises, one by one

And

know that is why I cannot love.

Mummy,

find it in you to forgive me

And

I will try to be bigger than my guilt

And

forgive myself.

Drawing Home

Were

I to draw my home, I don’t think

I

would do it quite like this drawing of yours.

All

these right angles and hinges bear no resemblance

To

my memories of suddenness and curves, odd shapes

And

our balancing act: four on a trapeze.

Still

I don’t resent your drawing.

I

rather like it, in fact; this way of making coherent

Scenes

of such randomness.

You

could play one camera. I could be the other.

We

could ask for a neutral third so that

Between

the three of us, we’d miss nothing.

You

could look for the big picture and I

For

nuance. The third camera, full-frontal, unblinking

Could

mediate. We might arrive at something

Between

your version and mine.

Geetha

Song Of The Rain VII

I

am dotted silver threads dropped from heaven

By

the gods. Nature then takes me, to adorn

Her

fields and valleys.

I

am beautiful pearls, plucked from the

Crown

of Ishtar by the daughter of Dawn

To

embellish the gardens.

When

I cry the hills laugh;

When

I humble myself the flowers rejoice;

When

I bow, all things are elated.

The

field and the cloud are lovers

And

between them I am a messenger of mercy.

I

quench the thirst of one;

I

cure the ailment of the other.

The

voice of thunder declares my arrival;

The

rainbow announces my departure.

I

am like earthly life, which begins at

The

feet of the mad elements and ends

Under

the upraised wings of death.

I

emerge from the heard of the sea

Soar

with the breeze. When I see a field in

Need,

I descend and embrace the flowers and

The

trees in a million little ways.

I

touch gently at the windows with my

Soft

fingers, and my announcement is a

Welcome

song. All can hear, but only

The

sensitive can understand.

The

heat in the air gives birth to me,

But

in turn I kill it,

As

woman overcomes man with

The

strength she takes from him.

I

am the sigh of the sea;

The

laughter of the field;

The

tears of heaven.

So

with love -

Sighs

from the deep sea of affection;

Laughter

from the colorful field of the spirit;

Tears

from the endless heaven of memories.

Thommo

There was an Old Man on whose nose

Most birds of the air could repose;

But they all flew away at the closing of day,

Which relieved that Old Man and his nose.

Most birds of the air could repose;

But they all flew away at the closing of day,

Which relieved that Old Man and his nose.

(Edward Lear)

A clergyman told from his text

How Samson was barbered and vexed,

And told it so true

That a man in the pew

Got rattled, and shouted out 'Next!"

Brigham

Young was never a neuter,

A

pansy or fairy or fruiter.

Where

ten thousand virgins

Succumbed

to his urgin’s,

We

now have the great state of Utah.

(Anon)

A

visitor once to Loch Ness

Met

the monster, which left him a mess.

They

returned his entrails

By

the regular mails

And

the rest of the stuff by express

There

was an old man from Bicester,

Walking

one day with his sister,

When

a bull with one poke

Tossed

her into an oak,

And

the silly old bloke never missed her.

-

Anon

A

French poodle espied in the hall

A

pool that a damp gamp let fall,

And

said, “Ah, oui, oui!

“This

time it’s not me,

“But

I’m bound to be blamed for it all.”

-

Anon

There

was a young fellow named Fisher

Who

was fishing for fish in a fissure,

When

a cod, with a grin,

Pulled

the fisherman in—

Now

they’re fishing the fissure for Fisher.

(Anon)

There

was a young lady of Kent,

Who

always said just what she meant.

People

said, “She’s a dear,

“So

unique, so sincere.”

But

they shunned her by common consent.

-

Anon

Cried

a slender young lady called Toni

With

a bottom exceedingly bony

"I'll

say this for my rump

Though

it may not be plump

It's

my own, not a silicone phoney!"

I

sat next to the Duchess at tea;

It

was just as I feared it would be.

Her

rumblings abdominal

Were

simply phenomenal,

And

everyone thought it was me!

A

skeleton once in Khartoum

Asked

a spirit up into his room;

They

spent the whole night

In

the eeriest fight

As

to which should be frightened of whom

There

was a man from Kerala

Who

refused to eat off an ela

When

asked why he wouldn’t

He

replied that he couldn’t

‘Cause

he was a cultured fella

Joe, one can get to hear Rabinder sangeet if you subscribe to Active Music from Tata Sky, along with other kinds of songs like English classics, Bhajans, Hindi Bollywood mix etc.

ReplyDeleteThere is an interesting take on Seamus Heaney's Blackberry Picking to be a sensual poem, "steamy". Could anyone sense that?

Dear Priya,

ReplyDeletere: Blackberry-Picking, is it 'steamy'?

I wrote, "Blackberry-Picking, is a sensuous description of the act of picking the berries and its transformation in the hands of those who handle it and eat it. Blackberries can become erotic subjects in the hands of a poet such as Heaney."

'Steamy' is generally used of visual scenes that excite the sexual appetite. I don't sense anything like that.

Tks for the TataSky info.

- joe