First Edition, 1989

This

reading had two occasions to celebrate, Eid al-Fitr, and Thommo's

impending departure to Istanbul to begin a 40-country drive around

the world in his Hyundai i20. We celebrated the breaking of

the fast with semia payasam and shammi kabab brought by

Zakia. And ordered up namkeen, tea and coffee from

the CYC kitchen for Thommo's journey –

he'll be leaving on Aug 2.

Zakia, Priya, Thommo

The

novel was all about buttling, and we were regaled with tales of

butlers who had survived the most extreme of

circumstances

without losing their aplomb. Stevens in the present novel is a

particularly

anal variety of the tribe. When

Joe used that word Thommo remarked there was a Bengali babu in his

office in Calcutta named অনল,

pronounced 'onol', who unfortunately spelled his name in English,

Anal.

Preeti & Pamela

Philosophically

this novel propounds the tale of one who habitually subordinates his

life's ambitions and goals to those of his master. Call it servility

in one sense, but it is the kind of supreme sacrifice of the ego

through which saints reach their goal by denying the self on the

altar of a higher good. The tragedy of Stevens the butler is that

his master ultimately fails, but not on

account of any lack of effort on Stevens' part.

Thommo, Preeti, Pamela, Joe

There's

also an abortive romance that denies Stevens the one chance he had of

rounding out the evening of his life, when nothing remains of the day.

In the film version it is with Mrs Benn (Emma Thompson) that Stevens

(Anthony Hopkins) silently sheds a tear in parting.

Panoramic view of the readers

Here

we are enjoying our double feast:

Thommo is Rs 5L short of the Rs 15L funding & Hyundai hasn't chipped in yet ...

Celebrating Eid Al-Fitr with Zakia's Semia Payasam & Shammi Kabab

And here's the group photograph at the end of

the reading:

Joe, Zakia, Priya, Thommo, KumKum, Talitha, Shoba, Pamela, Preeti

The

Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro

– Full

Record and Account of the Reading on July 22, 2015

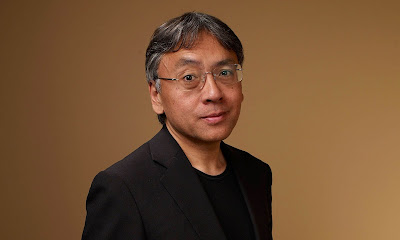

Kazuo Ishiguro

Thommo

has paid Rs 3,000/- to CYC for 12 sessions beginning with the one we

had on June 26, 2015. Money was collected from all the participants

at the last session, except Priya who paid for herself and Sunil

at this session. Anyone who has not paid – please do so asap, to

KumKum, since Thommo, our treasurer, is leaving on his safari.

The

dates for the next two sessions are

Poetry:

Thur Aug 13, 2015

Fiction:

Fri, Sep 18, 2015

(it will be Willa Cather's My

Antonia, instead of the Edgar Allan Poe stories as originally scheduled, because Thommo the co-selector of Poe will

be absent from Aug through Oct.)

The

attendance at this session:

Present:

Thommo, Priya, Pamela, Preeti,

KumKum, Joe, Talitha, Shoba, Zakia

Absent:

Ankush (not heard from),

Kavita (abroad in

Spain), Govind Sethunath (?), Vijay

(probably has

dropped out),

CJ (in Mumbai), Sunil (in Bengaluru for

daughter's admission), Gopa (in Bengaluru),

Saraswathy Rajendran (new member, missed first session for a 'brain'

function)

Introduction

to the Book

Talitha

as one of

the selectors of the book provided an introduction to the author and

the novel. See

Ishiguro

was born in Japan in Nagasaki in 1964 and at the age of 6 he came to

England with his parents on what was to be a temporary stay. But they

emigrated and he grew up in England and went to the University of

Kent in 1978 and did his Master's from the University of East

Anglia's creative-writing course in 1980. Such courses were imported

from America. Before he wrote The Remains of the Day,

there were two novels, the first set in Japan in Nagasaki. But

Ishiguro does not claim to know Japan, never having returned there

when he wrote the novel. The themes, Talitha said, for the first were

a widow, a widower for the second novel, and then this third

novel about the interior life of a butler set in the fifties. It won

the Booker prize in the year it was published, 1989, and Ishiguro

never looked back.

He

also writes lyrics for songs. In Never Let Me Go, a novel he

wrote in 2005 the title is taken from a pop-song in which the singer

embraces a pillow as she sings and appeals to Cathy H not to have her

organs distributed to numerous patients.

Ishiguro

writes about memories, digressions, distortions, and how they haunt.

Talitha said that between perception and memory there intervenes a

layer of self-deception. Two words that recur in this novel are

Dignity and Bantering. The former is the age-old goal of butlers and

it is almost an obsession with Stevens the butler in The Remains

of the Day. Bantering is a goal Stevens charts for his future

career under his new employer, Farraday.

Book

Reviews:

Salman

Rushdie upon re-reading the novel 23 years later says “The real

story here is that of a man destroyed by the ideas upon which he has

built his life.” Rushdie asks rhetorically “Why,

when the stranger tells him that he ought to put his feet up and

enjoy the evening of his life, is it so hard for Stevens to accept

such sensible, if banal, advice? What has blighted the remains of his

day?”

In

the above Paris Review interview this fragment of conversation takes

place:

INTERVIEWER

How

did the English setting come about for The

Remains of the Day?

ISHIGURO

It

started with a joke that my wife made. There was a journalist coming

to interview me for my first novel. And my wife said, Wouldn’t it

be funny if this person came in to ask you these serious, solemn

questions about your novel and you pretended that you were my butler?

We thought this was a very amusing idea. From then on I became

obsessed with the butler as a metaphor.

INTERVIEWER

As

a metaphor for what?

ISHIGURO

Two

things. One is a certain kind of emotional frostiness. The English

butler has to be terribly reserved and not have any personal reaction

to anything that happens around him. It seemed to be a good way of

getting into not just Englishness but the universal part of us that

is afraid of getting involved emotionally. The other is the butler as

an emblem of someone who leaves the big political decisions to

somebody else. He says, I’m just going to do my best to serve this

person, and by proxy I’ll be contributing to society, but I myself

will not make the big decisions. Many of us are in that position,

whether we live in democracies or not. Most of us aren’t where the

big decisions are made. We do our jobs, and we take pride in them,

and we hope that our little contribution is going to be used well.

The

New York Times had a very upbeat review:

“Kazuo

Ishiguro's tonal control of Stevens' repressive yet continually

reverberating first-person voice is dazzling.”

Michio

Kakutani of the NY Times, who has taken much more famous writers down

a peg or two, also praises the novel and calls it 'dazzling',

'elegiac':

The

Guardian also, looking back on the novel, applauds its triumph in the

Man Booker prize.

“Poignant,

subtly plotted and with the perfect unreliable narrator, Kazuo

Ishiguro's novel about a repressed servant deserved to rise above the

clamour surrounding the shortlist in the year of his Booker triumph.”

Stevens' Journey

Stevens

drives from Oxfordshire through Wiltshire, Somerset, Dorset and

Devon, and on to Cornwall. Dartmoor, Devon. This Google map charts

his journey:

More

about the route with photos is here:

Talitha

Talitha reading, with KumKum

Talitha read the passage in which Stevens while busy with household duties

and guests is called away to attend to his ailing father in his attic

room. The scene is quite traumatic, KumKum said. But the son manages

to exit, saying the situation downstairs is volatile and he'd best be

getting back. Stevens is bent on keeping a stiff upper lip. Thommo

mentioned that the Merchant-Ivory film he's seen several times on

local TV channels is fantastic because of the actors, Anthony Hopkins

and Emma Thompson.

In the film version Hopkins allows a bit more

emotion for Stevens. There are several contrasts between the film and

the novel (Ruth Prawer Jhabwala wrote the screenplay) and they are

described here:

Joe

added that the original screenplay was written by Harold Pinter, but

when a new writer was inducted he insisted on his contractual right

to have his name deleted from the film advertising totally. But he

was paid in full.

Talitha

told a story about some neta who was told during a function that his

wife had died, but he stayed on and completed the duties before he

went off to take care of his grief.

George Bush continuing to read the story My Pet Goat

Much more bizarre is the picture

of George Bush that was shown on a split screen on American TV, one

half with the World Trade Center towers crumbling, and the other half

with President George Bush continuing to read the story My Pet

Goat to children at a school in in Sarasota, FL, after having

been told by an aide of the terror attack on Sept 11, 2001:

Thommo

said the stiffness of Stevens stems from his not knowing what to say.

He's quite torn, said Talitha. Priya said the root cause of his

appearing indurate is Stevens' loyalty to his work, which his father

appreciated. Priya narrated how as children their great challenge was

to make the personal man-servant of their grandfather laugh; he was

grim and no amount of childish banter would cause a crease to appear

at the edge of his lips. He was the Indian equivalent, if not of a

butler, then of a valet.

Shashi Tharoor at the Oxford Union debate, July 20, 2015

Thommo

mentioned a debate in England at the Oxford Union when Shashi Tharoor

made an oration asking for reparations to India by Britain for its

horrible legacy of impoverishing India; he said the Hindi word 'loot'

had been introduced into the English language and into English

habits. See the video and text at

KumKum

KumKum's

reading featured the intimate scene, the only one

in the book, between Miss Kenton and Stevens:

Kenton

barges into the butler's pantry and tries to forcibly remove the book

Stevens

was reading to find what it was about.

What's in that book - Come on, let me see

KumKum said it brought to mind a Bengali song (click this link to hear the song) 'Prem

Ekbare Eseychhilo Nirobe

' i.e. love

came but once, quietly. Surely, it is extravagant, to classify this

encounter

in the pantry as

an amorous spark. Joe shifting to Hindi said that these two characters had absolutely

zero EQ. Priya agreed and characterised Stevens as a 'tube-light,' in

Bollywood terms.

Joe,

laughing, said Stevens may have been requisitioned to teach the facts

of life to Reggie, but he was aware only of the nether half of the body, and knew nothing at all about its manifestation in the heart

and the emotions! Thommo said such

a

deficit was precisely what he must have hoped to make good by reading

sentimental stories.

Joe

pointed out the build-up about the forthcoming meeting with Miss

Kenton as the West country journey progresses. It was obviously not

about filling a housekeeping vacancy – his unsatisfied

longing for romance must have been the motive. What a letdown finally by Ishiguro who has a stranger tell Stevens to put

up his feet and relax in the evening of his life – which

he is not going to do, for the obsession to excel in 'bantering'

has seized him in order to please his new American employer!

Zakia

Zakia

read from the end of the novel where Stevens meets a retired

old-timer and is told that evening is the best part of the day, and

now that the work's been done he can put up his feet and enjoy.

Talitha said the meaning of the novel is brought out in these lines,

"I gave my best to Lord Darlington. I gave him the very best I

had to give, and now – well – I find I do not have a great deal

more left to give." Thommo noted that Stevens may have put

himself in a strange place, for his new American employer may have

been happy with him as he was, but Stevens is not satisfied with

himself. Having achieved the pinnacle of dignity, now he must

overcome the more mundane challenge of 'bantering.'

About

Lord Darlington his previous employer, Talitha said he wasn't really

pro-Nazi so much as expressing the common realisation by that

time that the Versailles Treaty had imposed unbearable reparations on

Germany. Lord Keynes pointed this out in his famous essay The

Economic Consequences of Peace:

Keynes

had tried to prevent such onerous conditions being imposed, but

failed to convince the vengeful allies. Many connect the rise of

Hitler, and his popularity, to patriotic Germans with pride wishing

to give it back with interest. Lord Darlington was trying at best to

broker peace. Thommo noted that most of British royalty was German in

origin. Mountbatten was Battenberg. Preeti wondered if there was an

analogy between the conditions being imposed on Greece in the present

crisis, largely by Germany, with the harsh conditions at one time

imposed on Germany by the Versailles Treaty.

Priya

Priya

picked the climactic passage in which Stevens and Mrs Benn (the

former Miss Kenton) meet. But before that the definition of a butler

arose as an issue and Joe narrated a trivial fact he picked up about

Anthony Hopkins playing the butler in the film.

Hopkins as the butler – his life has been a foolish mistake

As a guest on a TV show, Hopkins let on that he got tips on how to play a butler from a real-life butler, Cyril Dickman, who served for 50 years at Buckingham Palace. Dickman said there was nothing to being a butler, really – when you're in the room it should be even more empty. Hence people remark on the stillness of Hopkins in the film role.

About

the passage Joe said when Stevens and Mrs Benn meet at the end, it is

the first time we are seeing both of them off-duty. Hence there is a

naturally relaxed tenor, in contrast to all their other encounters at

Darlington Hall. Even the talk seems more human, and quite different

from anything in the novel that takes place within the precincts of

Darlington Hall. Yes, for once they talk like normal people, said

Thommo.

Stevens and Mrs Benn at the parting

Thommo

spoke of the absolutes of hierarchy in the British class system that

pervades every aspect of life, including the life of servants. He

noted that in his experience when a junior assistant and a senior

assistant had to share the same digs, the senior chap drew a line in

the flat and insisted that the junior should never cross it!

Thommo

Thommo

took up for reading a portion of the book where Stevens dwells on

what makes a butler great. Stevens quotes from the Hayes Society of

butlers and their rules of admission. Talitha was struck by how much

Stevens reflected on his profession, and the merits by which one

could ascend the ladder of proficiency. Butlers put their job above

all else – the job of looking after their master and managing the

household.

In

this connection Priya said it happened once that Sudha Murthy, wife

of N. R. Narayana Murthy (co-founder of Infosys), was waiting outside Bombay House

(Tata HQ) when JRD Tata came out:

Narayana Murthy and Sudha Murthy

“One

day I was waiting for Murthy, my husband, to pick me up after office

hours. To my surprise I saw JRD standing next to me. I did not know

how to react. Yet again I started worrying about that postcard.

Looking back, I realise JRD had forgotten about it. It must have been

a small incident for him, but not so for me.

“Young

lady, why are you here?” he asked.

“Office

time is over.” I said, “Sir, I’m waiting for my husband to come

and pick me up.”

JRD

said, “It is getting dark and there’s no one in the corridor.

I’ll wait with you till your husband comes.”

I

was quite used to waiting for Murthy, but having JRD waiting

alongside made me extremely uncomfortable.

I

was nervous. Out of the corner of my eye I looked at him. He wore a

simple white pant and shirt. He was old, yet his face was glowing.

There wasn’t any air of superiority about him. I was thinking,

'Look at this person. He is a chairman, a well-respected man in our

country and he is waiting for the sake of an ordinary employee.'

Then

I saw Murthy and I rushed out. JRD called and said, “Young lady,

tell your husband never to make his wife wait again.”

Preeti

Preeti

read the account of the tiger in the dining room, discovered by the

butler of an ex-colonial who had travelled to India. The tiger was

dispatched without ceremony by the butler with three gunshots heard

off-stage by the guests in the drawing room. This story it seems was

related often by Stevens' father, and was as close as he “ever came

to reflecting critically on the profession he practised.”

Tiger in a distinguished home

After

the reading Joe got up, draped a napkin over his left hand and making

a bow as though to his master, whispered with butler-like precision,

“Excuse me, Sir, there appears to be a tiger in the dining room

...”

Pamela

Pamela

read a passage where Stevens becomes conscious that a witticism is

expected of him by the villagers in the inn when they warn him,

“you'll get woken by [the landlord's] missus shouting at him right

from the crack of dawn." So he gathers his wits and replies, “A

local variation on the cock crow, no doubt." The KRG readers too

laughed in the reading room.

Stevens mentions he listens to a radio

programme where witty repartees in the best of taste are exchanged.

He resolves once a day “to formulate three witticisms based on my

immediate surroundings at that moment.” This notion of a butler

practising humour consciously also provoked laughter in the audience.

All in all, it was a fine passage to bring out the mental exercises

that are required of a great butler. We enjoyed.

Joe

Joe's

Introduction to the novel

The

butler, Stevens, is a lonely repressed character, whose major tragedy

is that he is living someone else's life. As he tells Miss Kenton,

“my vocation will not be fulfilled until I have done all I can to

see his lordship through the great tasks he has set himself.”

Having

subjugated his life to that of his employer, Lord Darlington, it is

not surprising he misses quite a few opportunities for his own life:

companion-ship, closer filial attachment, a life in retirement,

children, and so on. Sadly, it turns out his employer Lord Darlington

was a Nazi sympathiser, not maliciously so but naively, which makes

the ensuing events of WWII doubly tragic for Stevens and his

employer. The other great altar on which the butler sacrifices

himself, is the grandiose idea of a butler's need for 'dignity',

regarding which there are many discourses, which grow tiresome.

At

the end of the novel Stevens gets some sage advice from a retired man

who had worked in houses: “We've

all got to put our feet up at some point. Look at me. Been happy as a

lark since the day I retired. All right, so neither of us are exactly

in our first flush of youth, but you've got to keep looking forward.”

Stevens concludes, “I

should adopt a more positive outlook and try to make the best of what

remains of my day.” And

the thought of developing his bantering skills and surprising his new

master, Mr Farraday, gives him a lift as the novel closes.

Joe considered the novel something of a failure for its inability to move

the reader to any degree of sympathy for the anal butler. It also

fails to provide the kind of lyrical language in which Thomas Hardy

could clothe his novels when describing much the same countryside

through which Stevens travels in his Ford. The stiff formality of the

language in the novel is meant to reflect the butler's persona, but

there are too many stiff people in the novel: his lordship, the

guests at Darlington Hall, Miss Kenton, even the new American owner

Mr Farraday. Ishiguro's range in this novel is manifestly limited in emotional range.

Joe

also complained of the lack of humour in the novel, but Talitha

protested saying many of the exchanges with Miss Kenton can be read

with a smile, and there's the tiger episode. Of course, Joe chose, as

he said, the only Jeeves-like passage in the novel, when Stevens is

tasked with furthering Reginald's education about the birds and the

bees.

Talitha said in the Wodehouse novels we do not get to see

things from Jeeves' side, and therefore are unaware of the perhaps

equally joyless professional life he led.

KumKum

added the generalisation that men don't understand or appreciate many

things and that's why Joe reacted negatively to the protagonist in

this novel, as well as to the tepid 'romantic' interest in Mis Kenton shown by Stevens. But

Pamela liked the lively stage manner in which Joe read the passage of

exchanges between a butler who is on the threshold of getting to the

point about procreation, and Reggie who manages to ease out of the

conversation at the critical moment.

Shoba

Shoba, who came late after a school engagement, read a Twitter-sized passage

from the very end, full of regret. Stevens exclaims, “All

those years I served [his lordship],

I trusted I was doing something worthwhile. I can't even say I made

my own mistakes.” The culminating cry,

“what dignity is there in that?"

is the mournful coda on which the novel

ends.

Even the much-vaunted dignity elaborated upon at such length in the novel ends up being a missed bus.

Even the much-vaunted dignity elaborated upon at such length in the novel ends up being a missed bus.

Priya,

ever-sympathetic Priya, said at this point she felt the loss of the

butler achingly. Shoba's comment was that Stevens is

first a butler, then a man.

Preeti

has been speaking to children in high schools professionally, and

finds that many of them are living their parents' desires for them,

rather than deciding for themselves. One 12th Standard girl said, “I'm lost, I

don't know what to do.” Preeti encouraged her to think and said it

is not a bad place

to be, for then you can find out by exploring. Her other comrades in chorus exclaimed, “This is the 12th. How come you

don't know?”

This provoked a discussion on the extent to which

children are striking out on their own now, with the new

opportunities in India, and not falling in line with the few

well-trodden paths chosen by kids in the fifties and sixties. KumKum said many

children of friends she knows are being more adventurous: wild-life

biologist, film director,

entrepreneur, … Thommo mentioned that lots of boys are going into

fashion-design to cater to the new markets for modern clothing so

that the young and the old with money to spare can look classy.

The

Readings

Talitha

p.

100 Stevens, the butler, tries to take care of an ailing father.

The

next day, the discussions in the drawing room appeared to reach a new

level of

intensity

and by lunchtime, the exchanges were becoming rather heated. My

impression

was that utterances were being directed accusingly, and with

increasing

boldness,

towards the armchair where M. Dupont sat fingering his beard, saying

little.

Whenever the conference adjourned, I noticed, as no doubt his

lordship did

with

some concern, that Mr Lewis would quickly take M. Dupont away to some

corner

or other where they could confer quietly. Indeed, once, shortly after

lunch, I

recall

I came upon the two gentlemen talking rather furtively just inside

the library

doorway,

and it was my distinct impression they broke off their discussion

upon

my

approach.

In

the meantime, my father's condition had grown neither better nor

worse. As I

understood,

he was asleep for much of the time, and indeed, I found him so on the

few

occasions I had a spare moment to ascend to that little attic room. I

did not

then

have a chance actually to converse with him until that second evening

after

the

return of his illness.

On

that occasion, too, my father was sleeping when I entered. But the

chambermaid

Miss Kenton had left in attendance stood up upon seeing me and

began

to shake my father's shoulder.

"Foolish

girl!" I exclaimed. "What do you think you are doing?"

"Mr

Stevens said to wake him if you returned, sir."

"Let

him sleep. It's exhaustion that's made him ill."

"He

said I had to, sir," the girl said, and again shook my father's

shoulder.

My

father opened his eyes, turned his head a little on the pillow, and

looked at me.

"I

hope Father is feeling better now," I said. He went on gazing at

me for a

moment,

then asked: "Everything in hand downstairs?'

"The

situation is rather volatile. It is just after six o'clock, so Father

can well

imagine

the atmosphere in the kitchen at this moment."

An

impatient look crossed my father's face.

"But

is everything in hand?" he said again.

"Yes,

I dare say you can rest assured on that.

I'm

very glad Father is feeling better."

With

some deliberation, he withdrew his arms from under the bedclothes and

gazed

tiredly at the backs of his hands. He continued to do this for some

time.

"I'm

glad Father is feeling so much better," I said again eventually.

"Now really, I'd

best

be getting back. As I say, the situation is rather volatile."

He

went on looking at his hands for a moment.

Then

he said slowly: "I hope I've been a good father to you."

I

laughed a little and said: "I'm so glad you're feeling better

now."

"I'm

proud of you. A good son. I hope I've been a good father to you. I

suppose I

haven't."

"I'm

afraid we're extremely busy now, but we can talk again in the

morning."

My

father was still looking at ,his hands as though he were faintly

irritated by

them.

"I'm

so glad you're feeling better now," I said again and took my

leave ..

KumKum

p.

173 Miss Kenton prises a book out of Stevens' hands in a scene of

intimacy

In

thinking about this recently, it seems possible that that odd

incident the evening Miss Kenton came into my pantry uninvited may

have marked a crucial turning point. Why it was she came to my pantry

I cannot remember with certainty. I have a feeling she may have come

bearing a vase of flowers 'to brighten things up', but then again, I

may be getting confused with the time she attempted the same thing

years earlier at the start of our acquaintanceship. I know for a fact

she tried to introduce flowers to my pantry on at least three

occasions over the years, but perhaps I am confused in believing this

to have been what brought her that particular evening. I might

emphasize, in any case, that notwithstanding our years of good

working relations, I had never allowed the situation to slip to one

in which the housekeeper was coming and going from my pantry all day.

The butler's pantry, as far as I am concerned, is a crucial office,

the heart of the house's operations, not unlike a general's

headquarters during a battle, and it is imperative that all things in

it are ordered – and left ordered – in precisely the way I wish

them to be. I have never been that sort of butler who allows all

sorts of people to wander in and out with their queries and grumbles.

If operations are to be conducted in a smootly co-ordinated way, it

is surely obvious that the butler's pantry must be the one place in

the house where privacy and solitude are guaranteed.

As

it happened, when she entered my pantry that evening, I was not in

fact engaged in professional matters. That is to say, it was towards

the end of the day during a quiet week and I had been enjoying a rare

hour or so off duty. As I say, I am not certain if Miss Kenton

entered with her vase of flowers, but I certainly do recall her

saying:

'Mr.

Stevens, your room looks even less accommodating at night than it

does in the day. The electric bulb is too dim, surely, for you to be

reading by.'

'It

is perfectly adequate, thank you, Miss Kenton.'

'Really,

Mr. Stevens, this room resembles a prison cell. All one needs is a

small bed in the corner and one could well imagine condemned men

spending their last hours here.'

Perhaps

I said something to this, I do not know. In any case, I did not look

up from my reading, and a few moments passed during which I waited

for Miss Kenton to excuse herself and leave. But then I heard her

say:

'Now

I wonder what it could be you are reading there, Mr. Stevens.'

'Simply

a book, Miss Kenton.'

'I

can see that, Mr. Stevens. But what sort of book – that is what

interests me.'

I

looked up to see Miss Kenton advancing towards me. I shut the book,

and clutching it to my person, rose to my feet.

'Really,

Miss Kenton,' I said, 'I must ask you to respect my privacy.'

'But

why are you so shy about your book, Mr.Stevens ? I rather suspect it

may be something rather racy.'

'It

is quite out of the question, Miss Kenton, that anything “racy', as

you put it, should be found on his lordship's shelves.'

…................

'Please

show me the volume you are holding, Mr.Stevens,' Miss Kenton said,

continuing her advance, 'and I will leave you to the pleasure of your

reading. What on earth can it be you are so anxious to hide?'

…...........

'I

wonder, is it a perfectly respectable volume, Mr Stevens, or are you

in fact protecting me from its shocking influence?'

Then

she was standing before me, and suddenly the atmosphere underwent a

peculiar change – almost as though the two of us had been suddenly

thrust on to some other plane of being altogether. I am afraid it is

not easy to describe clearly what I mean here. All I can say is that

everything around us suddenly became very still; it was my impression

that Miss Kenton's manner also underwent a sudden change; there was a

strange seriousness in her expression, and it struck me she seemed

almost frightened.

'Please,

Mr Stevens, let me see your book.'

She

reached forward and began gently to release he volume from my grasp.

I judged it best to look away while she did so, but with her person

positioned so closely, this could only be achieved by my twisting my

head away at a somewhat unnatural angle. Miss Kenton continued very

gently to prise the book away, practically one finger at a time. The

process seemed to take a very long time – throughout which I

managed to maintain my posture – until I finally heard her say:

'Good

gracious, Mr Stevens, it isn't anything so scandalous at all. Simply

a sentimental love story.'

Zakia

p.

252 – Stevens meets a stranger – the evening's the best part of

the day.

The

pier lights have been switched on and behind me a crowd of people

have just given

a loud cheer to greet this event. There is still plenty of daylight

left - the sky over the sea has turned a pale red - but it would seem

that all these people who have been gathering on this pier for the

past half-hour are now willing night to fall.This confirms very

aptly, I suppose, the point ,made by the man who until a little while

ago was sitting here beside me on this bench, and with whom I had my

curious discussion. His claim was that for a great many people, the

evening was the best part of the day, the part they most looked

forward to. And as I say, there would appear to be some truth in this

assertion, for why else would all these people give a spontaneous

cheer simply because the pier lights have come on?"

Of

course, the man had been speaking figuratively, but it is rather

interesting to see his words borne out so immediately at the literal

level. I would suppose he had been sitting here next to me for some

minutes without my noticing him, so absorbed had I become with my

recollections of meeting Miss Kenton two days ago. In fact, I do not

think I registered his presence on the bench at all until he declared

out loud:

"Sea

air does you a lot of good."

I

looked up and saw a heavily built man, probably in his late sixties,

wearing a rather tired tweed jacket, his shirt open at the neck. He

was gazing out over the water, perhaps at some seagulls in the far

distance, and so it was not at all clear that

he had been talking to

me. But since no one else responded, and since I could see no other

obvious persons close by who might do so, I eventually said:

"Yes,

I'm sure it does."

"The

doctor says it does you good. So I come up here as much as the

weather will let me."

The

man went on to tell me about his various ailments, only very

occasionally turning his eyes away from the sunset in order to give

me a nod or a grin. I really only started to pay any attention at all

when he happened to mention that until his retirement three years

ago, he had been a butler of a nearby house. On inquiring further, I

ascertained that the house had been a very small one in which he had

been the only full-time employee. When I asked him if he had ever

worked with a proper staff under him, perhaps before the war, he

replied:

"Oh,

in those days, I was just a footman. I wouldn't have had the know-how

to be a butler in those days. You'd be surprised what it involved

when you had those big houses you had then."

At

this point, I thought it appropriate to reveal my identity, and

although I am not sure 'Darlington Hall' meant anything to him, my

companion seemed suitably impressed.

"And

here I was trying to explain it all to you," he said with a

laugh. "Good job you told me when you did before I made a right

fool of myself. Just shows you never know who you're addressing when

you start talking to a stranger. So you had a big staff, I suppose.

Before the war, I mean."

He

was a cheerful fellow and seemed genuinely interested, so I confess I

did spend a little time telling him about Darlington Hall in former

days. In the main, I tried to convey to him some of the 'know-how',

as he put it, involved in overseeing large events of the sort we used

often to have. Indeed, I believe I even revealed to him several of my

professional 'secrets' designed to bring that extra bit out of staff,

as well as the various 'sleights-of-hand' - the equivalent of a

conjuror's - by which a butler could cause a thing to occur at just

the right time and place without guest seven glimpsing the often

large and complicated manoeuvre behind the operation. As I say, my

companion seemed genuinely interested, but after a time I felt I had

revealed enough and so concluded by saying:

"Of

course, things are quite different today under my present employer.

An American gentleman."

"American,

eh? Well, they're the only ones can afford it now. So you stayed on

with the house. Part of the package." He turned and gave me a

grin.

"Yes,"

I said, laughing a little. "As you say, part of the package."

The

man turned his gaze back to the sea again, took a deep breath and

sighed contentedly. We then proceeded to sit there together quietly

for several moments.

"The

fact is, of course," I said after a while, "I gave my best

to Lord Darlington. I gave him the very best I had to give, and now -

well - I find I do not have a great deal more left to give."

The

man said nothing, but nodded, so I went on:

"Since

my new employer Mr Farraday arrived, I've tried very hard, very hard

indeed, to provide the sort of service I would like him to have. I've

tried and tried, but whatever I do I find I am far from reaching the

standards I once set myself. More and more errors are appearing in my

work. Quite trivial in themselves – at least so far. But they're of

the sort I would never have made before, and I know what they

signify. Goodness knows, I've tried and tried, but it's no use. I've

given what I had to give. I gave it all to Lord Darlington."

"Oh

dear, mate. Here, you want a hankie? I've got one somewhere. Here we

are.

It's

fairly clean. Just blew my nose once this morning, that's all. Have a

go, mate."

"Oh

dear, no, thank you, it's quite all right. I'm very sorry, I'm afraid

the travelling has tired me. I'm very sorry."

"You

must have been very attached to this Lord whatever. And it's three

years since he passed away, you say? I can see you were very attached

to him, mate."

"Lord

Darlington wasn't a bad man. He wasn't a bad man at all. And at least

he had the privilege of being able to say at the end of his life that

he made his own mistakes. His lordship was a courageous man. He chose

a certain path in life, it proved to be a misguided one, but there,

he chose it, he can say that at least. As for myself, I cannot even

claim that. You see, I trusted. I trusted in his lordship's wisdom.

All those years I served him, I trusted I was doing something

worthwhile. I can't even say I made my own mistakes. Really - one has

to ask oneself – what dignity is there in that?"

"Now,

look, mate, I'm not sure I follow everything you're saying. But if

you ask me, your attitude's all wrong, see? Don't keep looking back

all the time, you're bound to get depressed. And all right, you can't

do your job as well as you used to.But it's the same for all of us,

see? We've all got to put our feet up at some point. Look at me. Been

happy as a lark since the day I retired. All right, so neither of us

are exactly in our first flush of youth, but you've got to keep

looking forward." And I believe it was then that he said:

"You've

got to enjoy yourself. The evening's the best part of the day. You've

done your day's work. Now you can put your feet up and enjoy it.

That's how I look at it. Ask anybody, they'll all tell you. The

evening's the best part of the day."

Priya

p.249

– Stevens and Mrs Benn (the former Miss Kenton) finally meet

The

rain was still falling steadily as we got out of the car and hurried

towards the shelter. This latter - a stone construct complete with a

tiled roof - looked very sturdy, as indeed it needed to be, standing

as it did in a highly exposed position against a background of empty

fields. Inside, the paint was peeling everywhere, but the place was

clean enough. Miss Ken ton seated herself on the bench provided,

while I remained on my feet where I could command a view of the

approaching bus. On the other side of the road, all I could see were

more farm fields; a line of telegraph poles led my eye over them into

the far distance.

After

we had been waiting in silence for a few minutes, I finally brought

myself to say:

"Excuse

me, Mrs Benn. But the fact is we may not meet again for a long time.

I wonder if you would perhaps permit me to ask you something of a

rather personal order. It is something that has been troubling me for

some time." "Certainly, Mr Stevens. We are old friends

after all."

"Indeed,

as you say, we are old friends. I simply wished to ask you, Mrs Benn.

Please -do not reply if you feel you shouldn't. But the fact is, the

letters I have had from you over the years, and in particular the

last letter, have tended to suggest that you are - how might one put

it? - rather unhappy. I simply wondered if you were being ill-treated

in some way. Forgive me, but as I say, it is something that has

worried me for some time. I would feel foolish had I come all this

way and seen you and not at least asked you."

"Mr

Stevens, there's no need to be so embarrassed.

We're

old friends, after all, are we not? In fact, I'm very touched you

should be so concerned. And I can put your mind at rest on this

matter absolutely. My husband does not mistreat me at all in any way.

He is not in the least a cruel or ill- tempered man."

"I

must say, Mrs Benn, that does take a load from my mind."

I

leaned forward in to the rain, looking for signs of the bus.

"I

can see you are not very satisfied, Mr Stevens," Miss Kenton

said. "Do you not believe me?"

"Oh,

it's not that, Mrs Benn, not that at all.

It's

just that the fact remains, you do not seem to have been happy over

the years. That is to say - forgive me - you have taken it on

yourself to leave your husband on a number of occasions. If he does

not mistreat you, then, well ... one is rather mystified as to the

cause of your unhappiness."

I

looked out into the drizzle again. Eventually, I heard Miss Kenton

say behind me: "Mr Stevens, how can I explain? I hardly know

myself why I do such things. But it's true, I've left three times

now." She paused a moment, during which time I continued to gaze

out towards the fields on the other side of the road. Then she said:

"I suppose, Mr Stevens, you're asking whether or not I love my

husband."

"Really,

Mrs Benn, I would hardly presume ... "

"I

feel I should answer you, Mr Stevens. As you say, we may not meet

again for many years. Yes, I do love my husband. I didn't at first. I

didn't at first for a long time. When I left Darlington Hall all

those years ago, I never realized I was really, truly leaving. I

believe I thought of it as simply another ruse, Mr Stevens, to annoy

you.

It

was a shock to come out here and find myself 'J married. For a long

time, I was very unhappy, very unhappy indeed. But then year after

year went by, there was the war, Catherine grew up, and one day I

realized I loved my husband. You spend so much time with someone, you

find you get used to him. He's a kind, steady man, and yes, Mr

Stevens, I've grown to love him."

Miss

Kenton fell silent again for a moment.

Then

she went on:

"But

that doesn't mean to say, of course, there aren't occasions now and

then - extremely desolate occasions - when you think to yourself:

'What a terrible mistake I've made with my life.' And you get to

thinking about a different life, a better life you might have had.

For instance, I get to thinking about a life I may have had with you,

Mr Stevens. And I suppose that's when I get angry over some trivial

little thing and leave. But each time I do so, I realize before long

- my rightful place is with my husband. After all, there's no turning

back the clock now. One can't be forever dwelling on what might have

been. One should realize one has as good as most, perhaps better, and

be grateful."

I

do not think I responded immediately, for it took me a moment or two

to fully digest these words of Miss Kenton. Moreover, as you might

appreciate, their implications were such as to provoke a certain

degree of sorrow within me. Indeed - why should I not admit it? - at

that moment, my heart was breaking. Before long, however, I turned to

her and said with a smile:

"You're

very correct, Mrs Benn. As you say, it is too late to turn back the

clock. Indeed, I would not be able to rest if I thought such ideas

were the cause of unhappiness for you and your husband. We must each

of us, as you point out, be grateful for what we do have. And from

what you tell me, Mrs Benn, you have reason to be contented. In fact

I would venture, what with Mr Benn retiring, and with grandchildren

on the way, that you and Mr Benn have some extremely happy years

before you. You really mustn't let any more foolish ideas come

between yourself and the happiness you deserve."

"Of

course, you're right, Mr Stevens. You're so kind."

"Ah,

Mrs Benn, that appears to be the bus coming now."

Thommo

p.119

– What is a butler?

IT

would seem there is a whole dimension to the question 'what is a

'great' butler?' I have hitherto not properly considered. It is, I

must say, a rather unsettling experience to realize this about a

matter so close to my heart, particularly one I have given much

thought to over the years. But it strikes me I may have been a little

hasty before in dismissing certain aspects of the Hayes Society's

criteria for membership. I have no wish, let me make clear, to

retract any of my ideas on 'dignity' and its crucial link with

'greatness'. But I have been thinking a little more about that other

pronouncement made by the Hayes Society – namely the admission that

it was a prerequisite for membership of the Society that 'the

applicant be attached to a distinguished household'. My feeling

remains, no less than before, that this represents a piece of

unthinking snobbery on the part of the Society. However, it occurs to

me that perhaps what one takes objection to is, specifically, the

outmoded understanding of what a 'distinguished household' is, rather

than to the general principle being expressed. Indeed, now that I

think further on the matter, I believe it may well be true to say it

is a prerequisite of greatness that one 'be attached to a

distinguished household' - so long as one takes 'distinguished' here

to have a meaning deeper than that understood by the Hayes Society.

In

fact, a comparison of how I might interpret 'a distinguished

household' with what the Hayes Society understood by that term

illuminates sharply, I believe, the fundamental difference between

the values of our generation of butlers and those of the previous

generation. When I say this, I am not merely drawing attention to the

fact that our generation had a less snobbish attitude as regards

which employers were landed gentry and which were 'business'. What I

am trying to say - and I do not think this an unfair comment - is

that we were a much more idealistic generation. Where our elders

might have been concerned with whether or not an employer was titled,

or otherwise from one of the 'old' families, we tended to concern

ourselves much more with the moral status of an employer. I do not

mean by this that we were preoccupied with our employers' private

behaviour. What I mean is that we were ambitious, in a way that would

have been unusual a generation before, to serve gentlemen who were,

so to speak, furthering the progress of humanity. It would have been

seen as a far worthier calling, for instance, to serve a gentleman

such as Mr George Ketteridge, who, however humble his beginnings, has

made an undeniable contribution to the future well-being of the

empire, than any gentleman, however aristocratic his origin, who

idled away his time in clubs or on golf courses.

In

practice, of course, many gentlemen from the noblest families have

tended to devote themselves to alleviating the great problems of the

day, and so, at a glance, it may have appeared that the ambitions of

our generation differed little from those of our predecessors. But I

can vouch there was a crucial distinction in attitude, reflected not

only in the sorts of things you would hear fellow professionals

express to each other, but in the way many of the most able persons

of our generation chose to leave one position for another. Such

decisions were no longer a matter simply of wages, the size of staff

at one's disposal or the splendour of a family name; for our

generation, I think it fair to say, professional prestige lay most

significantly in the moral worth of one's employer.

I

believe I can best highlight the difference between the generations

by expressing myself figuratively. Butlers of my father's generation,

I would say, tended to see the world in terms of a ladder - the

houses of royalty, dukes and the lords from the oldest families

placed at the top, those of 'new money' lower down and so on, until

one reached a point below which the hierarchy was determined simply

by wealth – or the lack of it. Any butler with ambition simply did

his best to climb as high up this ladder as possible, and by and

large, the higher he went, the greater was his professional prestige.

Such are, of course, precisely the values embodied in the Hayes

Society's idea of a 'distinguished household', and the fact that it

was confidently making such pronouncements as late as 1929 shows

clearly why the demise of that society was inevitable, if not long

overdue. For by that time, such thinking was quite out of step with

that of the finest men emerging to the forefront of our profession.

For our generation, I believe it is accurate to say, viewed the world

not as a ladder, but more as a wheel.

Preeti

p.

36 – The butler finds a tiger in the dining room.

There

was a certain story my father was fond of repeating over the years. I

recall listening to him tell it to visitors when I was a child, and

then later, when I was starting out as a footman under his

supervision. I remember him relating it again the first time I

returned to see him after gaining my first post as butler – to a Mr

and Mrs Muggeridge in their relatively modest house in Allshot,

Oxfordshire. Clearly the story meant much to him. My father's

generation was not one accustomed to discussing and analysing in the

way ours is and I believe the telling and retelling of this story was

as close as my father ever came to reflecting critically on the

profession he practised. As such, it gives a vital clue to his

thinking.

The

story was an apparently true one concerning a certain butler who had

travelled with his employer to India and served there for many years

maintaining amongst the native staff the same high standards he had

commanded in England. One afternoon, evidently, this butler had

entered the dining room to make sure all was well for dinner, when he

noticed a tiger languishing beneath the dining table. The butler had

left the dining room quietly, taking care to close the doors behind

him, and proceeded calmly to the drawing room where his employer was

taking tea with a number of visitors. There he attracted his

employer's attention with a polite cough, then whispered in the

latter's ear: "I'm very sorry, sir, but there appears to be a

tiger in the dining room. Perhaps you will permit the twelve-bores to

be used?"

And

according to legend, a few minutes later, the employer and his guests

heard three gun shots. When the butler reappeared in the drawing room

some time afterwards to refresh the teapots, the employer had

inquired if all was well. "Perfectly fine, thank you, sir,"

had come the reply. "Dinner will be served at the usual time and

I am pleased to say there will be no discernible traces left of the

recent occurrence by that time."

This

last phrase - 'no discernible traces left of the recent occurrence by

that time' - my father would repeat with a laugh and shake his head

admiringly.

Pamela

p.137

On witticisms

I

LODGED last night in an inn named the Coach and Horses a little way

outside the town of Taunton, Somerset. This being a thatch-roofed

cottage by the roadside, it had looked a conspicuously attractive

prospect from the Ford as I had approached in the last of the

daylight. The landlord led me up a timber stairway to a small room,

rather bare, but perfectly decent. When he inquired whether I had

dined, I asked him to serve me with a sandwich in my room, which

proved a perfectly satisfactory option as far as supper was

concerned. But then as the evening drew on, I began to feel a little

restless in my room, and in the end decided to descend to the bar

below to try a little of the local cider.

There

were five or six customers all gathered in a group around the bar -

one guessed from their appearance they were agricultural people of

one sort or another - but otherwise the room was empty. Acquiring a

tankard of cider from the landlord, I seated myself at a table a

little way away, intending to relax a little and collect my thoughts

concerning the day. It soon became clear, however, that these local

people were perturbed by my presence, feeling something of a need to

show hospitality. Whenever there was a break in their conversation,

one or the other of them would steal a glance in my direction as

though trying to find it in himself to approach me. Eventually one

raised his voice and said to me:

"It

seems you've let yourself in for a night upstairs here, sir."

When

I told him this was so, the speaker shook his head doubtfully and

remarked: "You won't get much of a sleep up there, sir. Not

unless you're fond of the sound of old Bob" - he indicated the

landlord - "banging away down here right the way into the night.

And then you'll get woken by his missus shouting at him right from

the crack of dawn."

Despite

the landlord's protests, this caused loud laughter all round.

"Is

that indeed so?" I said. And as I spoke, I was struck by the

thought - the same thought as had struck me on numerous occasions of

late in Mr Farraday's presence - that some sort of witty retort was

required "of me. Indeed, the local people were now observing a

polite silence, awaiting my next remark. I thus searched my

imagination and eventually declared:

"A

local variation on the cock crow, no doubt." At first the

silence continued, as though the local persons thought I intended to

elaborate further. But then noticing the mirthful expression on my

face, they broke into a laugh, though in a somewhat bemused fashion.

With this, they returned to their previous conversation, and I

exchanged no further words with them until exchanging good nights a

little while later.

I

had been rather pleased with my witticism when it had first come into

my head, and I must confess I was slightly disappointed it had not

been better received than it was. I was particularly disappointed, I

suppose, because I have been devoting some time and effort over

recent months to improving my skill in this very area. That is to

say, I have been endeavouring to add this skill to my professional

armoury so as to fulfil with confidence all Mr Farraday's

expectations with respect to bantering.

For

instance, I have of late taken to listening to the wireless in my

room whenever I find myself with a few spare moments – on those

occasions, say, when Mr Farraday is out for the evening. One

programme I listen to is called Twice a Week or More, which is in

fact broadcast three times each week, and basically comprises two

persons making humorous comments on a variety of topics raised by

readers' letters. I have been studying this programme because the

witticisms performed on it are always in the best of taste and, to my

mind, of a tone not at all out of keeping with the sort of bantering

Mr Farraday might expect on my part. Taking my cue from this

programme, I have devised a simple exercise which I try to perform at

least once a day; whenever an odd moment presents itself, I attempt

to formulate three witticisms based on my immediate surroundings at

that moment. Or, as a variation on this same exercise, I may attempt

to think of three witticisms based on the events of the past hour.

You

will perhaps appreciate then my disappointment concerning my

witticism yesterday evening. At first, I had thought it possible its

limited success was due to my not having spoken clearly enough. But

then the possibility occurred to me, once I had retired, that I might

actually have given these people offence. After all, it could easily

have been understood that I was suggesting the landlord's wife

resembled a cockerel - an intention that had not remotely entered my

head at the time. This thought continued to torment me as I tried to

sleep, and I had half a mind to make an apology to the landlord this

morning. But his mood towards me as he served breakfast seemed

perfectly cheerful and in the end I decided to let the matter rest.

But

this small episode is as good an illustration as any of the hazards

of uttering witticisms. By the very nature of a witticism, one is

given very little time to assess its various possible repercussions

before one is called to give voice to it, and one gravely risks

uttering all manner of unsuitable things if one has not first

acquired the necessary skill and experience.

Joe

p.86

Teaching Reggie the facts of life. Day Two – Morning (897 words)

"I'll

get to the point, Stevens. I happen to be the young man's godfather.

Accordingly,

Sir David has requested that I convey to young Reginald the facts of

life."

"Indeed,

sir."

"Sir

David himself finds the task rather daunting and suspects he will not

accomplish it before Reginald's wedding day."

"Indeed,

sir."

"The

point is, Stevens, I'm terribly busy. Sir David should know that, but

he's asked me none the less." His lordship paused and went on

studying his page.

"Do

I understand, sir," I said, "that you wish me to convey the

information to the young gentleman?"

"If

you don't mind, Stevens. Be an awful lot off my mind. Sir David

continues to ask me every couple of hours if I've done it yet."

"I

see, sir. It must be most trying under the present pressures."

"Of

course, this is far beyond the call of duty, Stevens."

"I

will do my best, sir. I may, however, have difficulty finding the

appropriate moment to convey such information."

"I'd

be very grateful if you'd even try, Stevens.

Awfully

decent of you. Look here, there's no need to make a song and dance of

it.

Just

convey the basic facts and be done with it. Simple approach is the

best, that's my advice, Stevens."

"Yes,

sir. I shall do my best."

"Jolly

grateful to you, Stevens. Let me know how you get on."

….

I happened to glance out of a window and spotted the figure of the young Mr Cardinal taking some fresh air around the grounds. He was clutching his attaché case as usual and I could see he was strolling slowly along the path that runs the outer perimeter of the lawn, deeply absorbed in thought. I was of course reminded of my mission regarding the young gentleman and it occurred to me that an outdoor setting, with the general proximity of nature, and in particular the example of the geese close at hand, would not be an unsuitable setting at all in which to convey the sort of message I was bearing. I could see, moreover, that if I were quickly to go outside and conceal my person behind the large rhododendron bush beside the path, it would not be long before Mr Cardinal came by. I would then be able to emerge and convey my message to him. It was not, admittedly, the most subtle of strategies, but you will appreciate that this particular task, though no doubt important in its way, hardly took the highest priority at that moment. There was a light frost covering the ground and much of the foliage, but it was a mild day for that time of the year. I crossed the grass quickly, placed my person behind the bush, and before long heard Mr Cardinal's footsteps approaching. Unfortunately, I misjudged slightly the timing of my emergence. I had intended to emerge while Mr Cardinal was still a reasonable distance away, so that he would see me in good time and suppose I was on my way to the summerhouse, or perhaps to the gardener's lodge. I could then have pretended to notice him for the first time and have engaged him in conversation in an impromptu manner. As it happened, I emerged a little late and I fear I rather startled the young gentleman, who immediately pulled his attaché case away from me and clutched it to his chest with both arms.

I happened to glance out of a window and spotted the figure of the young Mr Cardinal taking some fresh air around the grounds. He was clutching his attaché case as usual and I could see he was strolling slowly along the path that runs the outer perimeter of the lawn, deeply absorbed in thought. I was of course reminded of my mission regarding the young gentleman and it occurred to me that an outdoor setting, with the general proximity of nature, and in particular the example of the geese close at hand, would not be an unsuitable setting at all in which to convey the sort of message I was bearing. I could see, moreover, that if I were quickly to go outside and conceal my person behind the large rhododendron bush beside the path, it would not be long before Mr Cardinal came by. I would then be able to emerge and convey my message to him. It was not, admittedly, the most subtle of strategies, but you will appreciate that this particular task, though no doubt important in its way, hardly took the highest priority at that moment. There was a light frost covering the ground and much of the foliage, but it was a mild day for that time of the year. I crossed the grass quickly, placed my person behind the bush, and before long heard Mr Cardinal's footsteps approaching. Unfortunately, I misjudged slightly the timing of my emergence. I had intended to emerge while Mr Cardinal was still a reasonable distance away, so that he would see me in good time and suppose I was on my way to the summerhouse, or perhaps to the gardener's lodge. I could then have pretended to notice him for the first time and have engaged him in conversation in an impromptu manner. As it happened, I emerged a little late and I fear I rather startled the young gentleman, who immediately pulled his attaché case away from me and clutched it to his chest with both arms.

"I'm

very sorry, sir."

"My

goodness – Stevens. You gave me a shock.

I

thought things were hotting up a bit there."

"I'm

very sorry, sir. But as it happens I have something to convey to

you."

"My

goodness yes, you gave me quite a fright."

"If

I may come straight to the point, sir. You will notice the geese not

far from us."

"Geese?"

He looked around a little bewildered.

"Oh

yes. That's what they are."

"And

likewise the flowers and shrubs. This is not, in fact, the best time

of year to see them in their full glory, but you will appreciate,

sir, that with the arrival of spring, we will see a change – a very

special sort of change – in these surroundings."

"Yes,

I'm sure the grounds are not at their best just now. But to be

perfectly frank, Stevens, I wasn't paying much attention to the

glories of nature. It's all rather worrying. That M. Dupont's arrived

in the foulest mood imaginable. Last thing we wanted really."

"M.

Dupont has arrived here at this house, sir?"

"About

half an hour ago. He's in the most foul temper."

"Excuse

me, sir. I must attend to him straight away."

"Of

course, Stevens. Well, kind of you to have come out to talk to me."

"Please

excuse me, sir. As it happened, I had a word or two more to say on

the topic of – as you put it yourself – the glories of nature. If

you will indulge me by listening, I would be most grateful. But I am

afraid this will have to wait for another occasion. "

"Well,

I shall look forward to it, Stevens.

Though

I'm more of a fish man myself. I know all about fish, fresh water and

salt."

"All

living creatures will be relevant to our forthcoming discussion, sir.

However, you must now please excuse me. I had no idea M. Dupont had

arrived."

Shoba

p.255

Regrets

"Lord Darlington wasn't a bad man. He wasn't a bad man at all. And at least he had the privilege of being able to say at the end of his life that he made his own mistakes. His lordship was a courageous man. He chose a certain path in life, it proved to be a misguided one, but there, he chose it, he can say that at least. As for myself, I cannot even claim that. You see, I trusted. I trusted in his lordship's wisdom. All those years I served him, I trusted I was doing something worthwhile. I can't even say I made my own mistakes. Really – one has to ask oneself – what dignity is there in that?"

"Lord Darlington wasn't a bad man. He wasn't a bad man at all. And at least he had the privilege of being able to say at the end of his life that he made his own mistakes. His lordship was a courageous man. He chose a certain path in life, it proved to be a misguided one, but there, he chose it, he can say that at least. As for myself, I cannot even claim that. You see, I trusted. I trusted in his lordship's wisdom. All those years I served him, I trusted I was doing something worthwhile. I can't even say I made my own mistakes. Really – one has to ask oneself – what dignity is there in that?"

Joe's latest blog post is an excellent report on KRG's July 22, 2015 Session.

ReplyDeleteApart from Joe, the rest of us loved Ishiguro's 'The Remains of The Day' and his style of narration. Even Joe gleaned from the book a couple of humorous paragraphs to read to us. And he read very well, evincing the drama and the humour latent in those paragraphs.

I was surprised that the post even had a link to the old Bengali song I vaguely remembered, and thought may have the same theme as the paragraphs I chose to read. After listening to the song when I clicked the link, I am convinced the lyrics truly represent Steven's trepidation in recognising LOVE when it appeared before him.

Well done Joe!

Bon Voyage to our evergreen explorer, Thommo! We wish him well on his long drive through Turkey and many countries in Europe, and through USA. We hope he will return safely with tall tales to delight us.

KumKum