Puckoon 1963 edition

Comic adventures have featured in our reading every year. This time it was a novel by Spike Milligan, best known in Britain as the creator and writer of The Goon Show, a half-hour radio comedy that ran on BBC in the fifties, starring Spike Milligan, Peter Sellers and Harry Secombe. Milligan had a nervous breakdown from authoring scores of episodes over the years, but later he was given a bunch of comedy writers to assist him, preserving his brand of off-key humour.

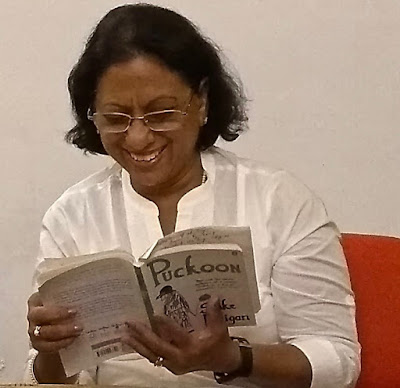

Devika

Saras discusses

Attenborough says, “Spike's humour was all about irreverence, … irreverence is an essential part of our culture. I admire that enormously.” Spike was meant to be in the film; however ill-health prevented his participating, though he saw the film before he died. His daughter Jane acted as the fierce wife of Dan Madigan.

Puckoon film poster 2002

Our readers concurred that the book was a riot of laughter almost all the way through. The individual pictures will bear testimony to their enjoyment, but here they are at the end, completely chortled out, barely a smile left with which to crease their faces.

Geetha, Devika, Saras, Thommo, Geetha Joseph, Pamela, Priya, (seated) Hemjit

Spike Milligan 1918 - 2002

Full Account and Record of Reading the novel Puckoon by Spike Milligan – May 31, 2019

Present: Priya, Thomo, Saras, Devika, Hemjit, Geetha, Kavita, Pamela

Virtually Present: Joe, Gopa through recorded passages

Guest: Geetha Joseph

The book was selected by Priya and Thommo. Thommo introduced the author and the book to the reading group. Grateful thanks to Thommo for taking notes on the session, and to Priya for the pictures.

A younger Spike Milligan

His parents were Catholics and he studied at Catholic schools in various parts of India. After his schooling he relocated to the United Kingdom where he spent the rest of his life for the most part. While in the UK he changed his name to Spike Milligan because he did not like his first name Terence.

He returned to England after his father was mustered out of the army in India, and found it difficult adjust at first. Spike joined the army during World War II and had a jolly time, playing in an army band with his friends (he was a fairly good trumpet player) until his unit was peppered with mortars by the Germans on the Italian front. When a shell burst near his head he was wounded, and shell-shocked.

Spike went on to be well known as a British-Irish comedian, writer, poet, playwright and actor. His father was Irish and his mother English.

He is most famous for The Goon Show, a British radio program, which he co-created in the fifties; he was the main writer and a principal member of the cast.

Milligan wrote and edited many books, including Puckoon, a comic novel, which was first published in 1963; it went into a score of reprints or more. It has never been out of print and sold over 6m copies by 2002. It’s his major work of fiction, set in 1924. It details comically what happened in the fictional Irish village of Puckoon when the partition of Ireland happened. The feckless Boundary Commission placed the new border right through the village, with most of it in the independent Irish Free State, but a significant part called Northern Ireland placed in union with the United Kingdom.

Thommo mentioned that the Irish Border was actually just as it was described in Puckoon. There were quite a few buildings which straddled both sides of the border. He recalled reading a short story in which the owner of such a property used it to smuggle contraband between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Saras said it was one of Jeffrey Archer's short stories, titled Both Sides Against the Middle.

There are several adaptations of the novel Puckoon. There is an abridged audiobook version, read by the author. You can also find an audio version on Youtube at

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DLcFqE6CLbs

Puckoon (Pt. 1) 27m 53s audio

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oeudGA8xD8Q

Puckoon (Pt. 2) 29m 56s audio

A film adaptation by Terence Ryan, was released in 2002. Our hero is renamed ‘Dan Madigan’ and Richard Attenborough narrated because Spike Milligan was not in good health. The film was shot in Belfast, Northern Ireland. You can read a review of the film and commentary by Richard Attenborough in The Guardian at

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2002/jul/23/artsfeatures

In 2009 Puckoon was adapted for the stage, and toured Ireland and the United Kingdom in 2009 and 2011. The 2016 tour of the play is presented at

http://www.spikemilliganspuckoon.com/

Milligan also wrote a seven-volume autobiographical account of his time serving during the Second World War, beginning with Adolf Hitler: My Part in His Downfall. Spike also wrote comical verse, a lot of it written for children, best known of which is Silly Verse for Kids which he brought out in 1959.

Spike became an Irish citizen in 1962 when the Commonwealth Immigrants Act removed Indian-born Milligan's automatic right to British citizenship. He was able to do so because his father was Irish-born. This is how he narrates his acquisition of Irish citizenship:

“I had a British passport, but when I went to get it renewed, and said my father was born in Ireland before 1900, they said I couldn't have a British passport. So I said, fuck you. I went to the Irish Embassy and I said: ‘My name's Spike Milligan, can I have a passport?’ And they said, ‘Oh yes! We're short of people.’”

Here’s a 1996 documentary exploring the life and work of Spike Milligan. If the readers enjoyed the laughter provoked by the novel, then more such laughter will split their sides from the interviews with Spike Milligan featured in this documentary. He is Goon, but not forgotten, says the subtitle:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=185&v=ZQU9SG5C3P4

Here are some Spike Milligan Quotes:

“Contraceptives should be used on all conceivable occasions.”

“How long was I in the army? Five foot eleven.”

“I have the body of an eighteen year old. I keep it in the fridge.”

“Is there anything worn under the kilt? No, it's all in perfect working order.”

“Money can't buy friends, but you get a better class of enemy.”

“A man can’t have everything - I mean, where would he put it?”

“I don't mind dying, I just don't want to be there at the time.” (Woody Allen also said something similar much later: “I am not afraid of death. I just don’t want to be there when it happens.”)

“One man retreating is called running away. But a whole regiment running away is called a retreat.”

Diligent Reader Exercises (DRE) - responses by June 21 to Joe will be read at the next session

1. Complete the quatrain – not in the sedate manner of an Anglican bishop – but as you imagine Spike Milligan might have finished it. End rhyme may be abandoned if it is an undue constraint)

Once knew a Judy in Dubleen town

Her eyes were blue and her hair was brown

One night on the grass I got her downnnn

....

2. List a couple of words you picked up reading Puckoon, and their meanings.

It was decided to read in ascending order of the pages selected by the readers. The session began with Joe's recorded selection which was from the earliest portion of the book. Unfortunately, the recording was not downloaded and available to play, so Thommo read Joe's selection. But Joe’s recorded animation of the episode of Dan Milligan’s court-martial is linked here below.

Joe

He read the passage in which Dan Milligan responds to the court-martial for cowardice in Ch 2. Milligan insists in his defence he was not running away, but retreating.

The audio is here:

Next, Thommo read his own selection which was only a couple of pages later.

Thommo

Thommo

Thommo mentioned that although the book was hilarious it contained some very profound statements such as this: Bureaucracy was the counterpart of cancer, it grew bigger and destroyed everything except itself.

Geetha in the meantime took over KumKum's role of shepherding the readers along.

Devika then read her selection which was just a few pages after Thommo's, on the profound subject of dying and what comes after.

Devika

Devika

She commented on the fictional relationship between the author and the main character Dan Milligan and of each addressing the other directly. Saras, too, commented on this.

It was observed that the word Chinee was yet another example of Spike's familiarity with India because it is the North Indian word for Chinese.

Geetha

Geetha

Geetha read her selection with dramatic flourish even simulating the ATISHOOOO sneeze that ejected Mr. Meredith's dentures.

Hemjit

Hemjit

Hemjit’s passage covered several predicaments: protesting the border separating Catholics and Protestants, finding valid excuses for divorce, and how wily solicitors solve the problem of a person who has willed all his assets to himself after death.

Hemjit said that the book was a laugh riot almost all the way through; yet there were some very poignant lines in it. This is one from his selection: Money couldn't buy you friends, but you got a better class of enemy.

Kavita

Kavita

Kavita’s passage deals with the unique experiences of a Chinese man trying to find work in Dublin, escaping from the poverty of his homeland. The narration is riddled with humour at every turn.

Kavita laughed almost all the way through her reading. She had to go early and but left a bag of lovely cookies for the members to enjoy.

Cake by Devika and Biscuits by Kavita

Priya was able to download Gopa's selection on her phone and members heard Gopa's voice through Priya's phone.

Gopa

The passage starts with candid photography of women, and arranging to have a man with ‘leg trouble right up to his neck’ captured on camera. The scenes are completely zany. Here is the audio:

Geetha Joseph

Geetha Joseph

She read from a short passage about the escape of a panther from The World's Finest Animal Circus of Giulio Caesar.

Although she did not like the book she found it hilarious and couldn't stop laughing. The pages following Geetha's selection dealt with a giant of a man called O'Mara felling the panther with one blow. Thommo thought that Spike's selection of the Gaelic name O’Mara was a deliberate play on the Hindi word for killing, given Spike’s familiarity with the language from his youth.

Pamela

Pamela

Pamela mentioned that she had read Scarlett, a 1991 novel by Alexandra Ripley, written as a sequel to Margaret Mitchell's 1936 novel, Gone with the Wind, which contained a lot of information about Ireland, including a meeting with a group of terrorists in that country.

Saras

The scene depicted is of unearthing TNT from the coffin of a buried person as the recruits are led by Father Rudden. The quaint aspect is that ‘the power of de author’ comes into play in arranging what happens in the scene!

Saras talked about the other books that Spike had written. The imaginary interaction in the book between the fictional Dan Milligan and the author Spike Milligan is notable as a literary device.

In the context of the smuggling of TNT in Saras’ selection, Thommo mentioned that he had occasion to enter the foyer of the Hotel Europa in Belfast, bombed no less than 29 times - perhaps the most bombed building in history.

Priya

Priya

Colonic irrigation and enemas had made the exile of the Count Fritz Von Krappenhauser an endless holiday. He had fled to N Ireland and bought 10,000 acres and a castle, but one morning, powder leaked from the 12-bore cartridges of his shot gun and mixed with the ash of a cigar he flicked and BOOM! went the Count, and the Castle and all. Some enema!

It was observed that the incident described was a flashback in which the great-great grandfather of Mortimer Wregg, one of the firemen, had almost extinguished the greatest and most expensive fire in Irish history.

Priya said there was an element of pathos in the book and read the bit about O'Mara’s ex-wife killing their three little children by slitting their throats, and yet continuing to keep their beds made up and sleeping every night with a teddy bear and a dolly clutched in his arms.

Devika loved the part where Milligan reflects about life in heaven, which he felt was strange and mysterious. And in spite of modern people knowing so much about everything, the after-life remains an unknown.

Devika also read ‘Smile’, a poem by Spike Milligan. Recall: the first reader to introduce Spike Milligan to KRG was Gopa in 2015 when she read a poem of his at our December session.

Everyone wondered what the Irish border would be like after Brexit. It was noted that for the moment one can fly into Belfast in Northern Ireland on a UK visa and drive down to Dublin in the Republic of Ireland without crossing any visible border. However, one can't fly into Dublin without an Irish visa, as the Schengen visa does not cover the Republic of Ireland.

The session was thoroughly enjoyed by all the readers and the Yacht Club's library erupted constantly in laughter. The cookies provided by Kavita and the scrumptious chocolate cake baked by Devika provided a fitting end to the session.

The poetry session in June will be on Friday the 28th, 2019, as agreed earlier.

Reading Passages

Joe

Dan Milligan responds to his court-martial for cowardice

The Milligan had suffered from his legs terribly. During the war in Italy. While his mind was full of great heroisms under shell fire, his legs were carrying the idea, at speed, in the opposite direction. The Battery Major had not understood.

'Gunner Milligan? You have been acting like a coward.'

'No sir, not true. I'm a hero wid coward's legs, I'm a hero from the waist up.'

'Silence! Why did you leave your post?'

'It had woodworm in it, sir, the roof of the trench was falling in.'

'Silence! You acted like a coward!'

'I wasn't acting sir!'

'I could have you shot!'

'Shot? Why didn't they shoot me in peacetime? I was still the same coward.'

'Men like you are a waste of time in war. Understand?' 'Oh? Well den! Men like you are a waste of time in peace.'

'Silence when you speak to an officer,' shouted the Sgt. Major at Milligan's neck.

All his arguments were of no avail in the face of military authority. He was court martialled, surrounded by clanking top brass who were not cowards and therefore biased. 'I may be a coward, I'm not denying dat sir,' Milligan told the prosecution.

'But you can't really blame me for being a coward. If I am, then you might as well hold me responsible for the shape of me nose, the colour of me hair and the size of me feet.'

'Gunner Milligan,' Captain Martin stroked a cavalry moustache on an infantry face. 'Gunner Milligan,' he said. 'Your personal evaluations of cowardice do not concern the court. To refresh your memory I will read the precise military definition of the word.'

He took a book of King's Regulations, opened a marked page and read 'Cowardice'. Here he paused and gave Milligan a look.

He continued:

'Defection in the face of the enemy. Running away.'

'I was not running away sir, I was retreating.'

'The whole of your Regiment were advancing, and you decided to retreat?'

'Isn't dat what you calls personal initiative?'

'Your action might have caused your comrades to panic and retreat.'

'Oh, I see! One man retreating is called running away, but a whole Regiment running away is called a retreat? I demand to be tried by cowards!'

A light, commissioned-ranks-only laugh passed around the court. But this was no laughing matter. These lunatics could have him shot. 'Have you anything further to add?' asked Captain Martin.

'Yes,' said Milligan. 'Plenty. For one ting I had no desire to partake in dis war. I was dragged in. I warned the Medical Officer, I told him I was a coward, and he marked me A.1. for Active Service. I gave everyone fair warning! I told me Battery Major before it started, I even wrote to Field Marshal Montgomery. Yes, I warned everybody, and now you're all acting surprised?'

Even as Milligan spoke his mind, three non- cowardly judges made a mental note of Guilty.

Thommo

Milligan is booted out by his wife to look for grass-cutting work, and other tangential merriment.

The sound of a male bicycle frame drew the priest's attention. There coming up the drive was the worst Catholic since Genghis

'Ah, top of the morning to yez, Father,' Milligan said dismounting.

'Well, well, Dan Milligan.' There was surprise and pleasure in the priest's voice. 'Tell me, Dan, what are you doing so far from your dear bed?'

'I'm feeling much better, Father.'

'Oh? You been ill then?'

'No, but I'm feeling much better now dan I felt before.' There was a short pause, then a longer one, but so close were they together, you couldn't tell the difference.

'It's unexpectedly hot fer dis time of the year, Father.'

'Very hot, Milligan. Almost hot enough to burn a man's conscience, eh?'

'Ha ha, yes, Father,' he laughed weakly, his eyes two revelations of guilt.

'When did you last come to church, Milligan?'

'Oh, er, I forget — but I got it on me Baptismal certificate.'

The priest gave Milligan a long meaning stare which Milligan did not know the meaning of. Then the Milligan, still holding his bike, sat down next to the priest. 'By Gor Father, wot you tink of dis weather?'

'Oh, it's hot all right,' said Father Rudden relighting his pipe. Producing a small clay decoy pipe, Milligan started to pat his empty pockets. 'Here,' said the priest, throwing him his tobacco pouch.

'Oh tank you Father, an unexpected little treat.' Together the two men sat in silence; sometimes they stood in silence which after all is sitting in silence only higher up. An occasional signal of smoke escaped from the bowl and scurried towards heaven.

'Now Milligan,' the priest eventually said, 'what is the purpose of this visit?' Milligan knew that this was, as the Spaniards say, 'El Momento de la Verdad', mind you, he didn't think it in Spanish, but if he had, that's what it would have looked like.

'Well Father,' he began, puffing to a match, 'well, I — "puff-puff-puff' — I come to see — "puff- puff' — if dis grass cuttin' — job — "puff-puff' — is still goin'.'

The inquiry shook the priest into stunned silence. In that brief moment the Milligan leaped on to his bike with a 'Ah well, so the job's gone, good-bye.' The priest recovered quickly, restraining Milligan by the seat of the trousers. 'Oh, steady Father,' gasped Milligan, 'dem's more then me trousers yer clutchin'.' 'Sorry, Milligan,' said the priest, releasing his grip. 'We celibates are inclined to forget them parts.' 'Well you can forget mine fer a start,' thought Milligan. Why in God's name did men have to have such tender genitals. He had asked his grandfather that question. 'Don't worry 'bout yer old genitals lad,' said the old man, 'they’ll stand up fer themselves.'

Devika

On the profound subject of dying and what comes after

As Milligan laboured unevenly through the afternoon, long overgrown tombstones came to light,

R.I.P .

Tom Conlon O’Rourke.

Not Dead, just Sleeping.

‘He’s not kiddin’ anyone but himself,’ Milligan chuckled irreverently. What was all dis dyin’ about, anyhow? It was a strange and mysterious thing, no matter how you looked at it. ‘I wonder what heaven is really like? Must be pretty crowded by now, it’s been goin’ a long time.’ Did they have good lunches? Pity dere was so little information. Now, if there was more brochures on the place, more people might be interested in going dere. Dat’s what the church needed, a good Public Relations man. ‘Come to heaven where it’s real cool.’ ‘Come to heaven and enjoy the rest.’ ‘Come to heaven where old friends meet, book now to avoid disappointment!’ Little catch phrases like dat would do the place a power of good. Mind you, dere were other questions, like did people come back to earth after they die, like them Buddhists say. In dat religion you got to come back as an animal. Mmm, a cat! Dat’s the best animal to come back as, sleep all day, independent, ha! that was the life, stretched out in front of a fire, but no, Oh hell, they might give me that terrible cat operation, no no I forgot about that. Come to think of it, who the hell wants to come back again anyhow? Now, honest, how many people in life have had a good enough time to come back? Of course if you could come back as a woman you could see the other side of life? By gor, dat would be an experience, suppose you wakes up one morning and finds you’re a woman? What would he do? Go for a walk and see what happens. Oh yes, all this dyin’ was a funny business, still, it was better to believe in God than not. You certainly couldn’t believe in men. Bernard Shaw said ‘Every man over forty is a scoundrel’, ha ha ha, Milligan laughed aloud, ‘Every one round dese parts is a scoundrel at sixteen!’ Bernard Shaw, dere was a great man, the Irish Noel Coward. A tiny insect with wings hovered stock still in front of Milligan’s face. ‘I wonder if he’s tryin’ to hypnotize me,’ he thought, waving the creature away.

Geetha

The Boundary Commissioners argue about the last few miles of the frontier between south and north. Dentures play a large part in the proceedings.

It was to be a solemn occasion......sealed her from all harm and pleasure.

It was to be a solemn occasion. As James Joyce says, ‘real hairy’. In a brown and upstairs room at the Duke of Wellington Hotel ‘Ireland’, to quote an I.R.A . leaflet, was being ‘torn in two by TRATERS ’, the last word being in red. At every door and window, standing, sitting, looking, listening, soldiers from both factions stood guard. Beyond them, another perimeter of men set off as listening posts. With the I.R.A . about, nobody was taking any chances, least of all the I.R.A . who were all home in bed. Rain was falling, and the men stood close to the walls for shelter. Inside, several high-ranking, grim-faced Boundary Commissioners from both sides faced each other across a giant map of Ireland.

On one corner rested a mess of empty tea cups; half-eaten sandwiches, their edges curling, lay helpless in a thin film of tea that trembled on the floor of the tray. Lighting the scene was a mean yellow bulb covered with generations of fly specks. Across the map, running from right to left, was a thick red pencil line that terminated just short of the Atlantic. It was the threatened new border. In its path lay sleeping Puckoon. Points of interest and under discussion were represented by a forest of little flags on pins, forever being displaced by table-thumping members of the Commission. For ten whole days now they had argued the last few miles of frontier. Tempers were frayed, agreements infrequent and weak bladders put to the test. Mr Haggerty was complaining about the Ulster representatives' indecisiveness.

He was breathing heavily from a short fat round body packed into a blue serge suit, every seam of which was under considerable pressure from the contents. He lost his temper and — more frequently — his arguments.

'You'll all be in the Republic one day, so there,' he thumped the map with a fat furious fist, displacing numerous flags.

Immediately, Mr Neville Thwick, a thin, veiny, eel-like man with acne, deftly replaced the flags. He had volunteered for the job. Insignificant since birth, sticking pins in maps gave him the secret power he craved. The walls of his attic bed- sitting room were hung with treasured maps of famous battles, campaigns and sorties. Solfarino, Malplaquet, Plassey, the Somme, the Boyne. There were three hundred in scrolls under his bed and scores more, carefully indexed, placed on every shelf and ledge. He possessed his own pin- making machine, and a small triangular printers' guillotine for manufacturing flags. Power, what power this combination held!

Every night Mr Thwick would leave his desk at Mills & Crotts bird-seed factory and catch the 33a tram to his home. On arrival he would prepare tea and perhaps a one-egg omelette. After a wash and shave he would place a battle-map of his choosing on the floor. From a chest he would select a military uniform suitable for the period. Dressed so, he would pace the room, making little battle noises with his mouth. Last Sunday had seen his greatest victory. After much deliberation he had decided to re-contest Waterloo. Dressed as Napoleon he placed himself at the head of the French army of 600 flags. The thought of it had made him weak, he felt giddy and sat down to massage his legs. After a measure of ginger wine, he felt strong enough to continue. There followed a night of move and counter move. Despite knockings on the walls from sleepless neighbours, he continued his battle noises, thrusting flags hither and thither. He force- marched a platoon of French Chasseurs till their points were blunt, he reinforced Blucher with a secret supply of mercenary flags from Ireland and destroyed the Prussian threat to his flank. At three o'clock he played his master stroke. He thrust a white flag right into the English H.Q.

Wellington and his staff were humbled in the dust. To the accompaniment of the people around hammering with shoe heels and brooms, he accepted Wellington's sword and surrender. Then victorious to bed with a hot water bottle and a spoonful of Dr Clarkson-Spock's Chest Elixir. Next morning, dressed as a civilian, with very little resistance, Wellington's conqueror was evicted by his landlady.

Living in the Y.M.C.A. curtailed his activities, but the present job kept him in practice until conditions changed. After all, peace, as any good general knew, couldn't last for ever, and the only way to end wars was to have them.

'Mr Haggerty, sir.' The febrile, castrato voice of Mr Meredith was raised in protest. 'Mr Haggerty,' he repeated, as he rose to his feet. One could see how very old he was, how very thin he was, and falling back into his seat, how very weak he was. 'Mr Haggerty,' he said for the third time, his pale hands flapping like mating butterflies, 'I protest at —'. He stopped suddenly, eyes closed, lids quivering, head back. 'Ahhhhhh — AHHHI--IH —' A pause, his face taking on that agonized look of the unborn sneeze. 'Sorry about that,' he muttered, wiping his eyes. 'Now.' He became stronger. 'I was saying th — ATISHOOOOO!' thundered the unexpected; 'AHTISHOOOO! !' The convulsion shot his dentures the length of the room. Thud! went his head on the table, 'ATISHOO!' down went the flags, in sprang Mr Thwick. 'Oh!' shrieked Mrs Eels, a set of heavy dentures landing on her lap. Meredith lay back, spit-speckled, white and exhausted, his face folded in two.

Mrs Eels returned his teeth on a plate covered with her 'kerchief. 'No thank you, dear,' said the still muzzy Meredith, 'I couldn't eat another thing.'

With his back to the map table and accompanied by terrifying clicks and clacks, Meredith wrestled to replace his prodigal dentures; finally, he turned to continue his speech, but remained silent. Staring pop-eyed, he staggered round the room pointing to his mouth, making mute sounds and getting redder and redder.

'Ahhhh! I see what the trouble is,' said Haggerty, pulling down Meredith's lower lip. 'He's put his choppers in upside down, someone fetch me a screwdriver.'

Mr Meredith's aide-de-camp, Captain Clarke, called for a short pause while 'our spokesman's dentures are readjusted and his dignity restored'. A regular soldier, he was known to his subordinates as 'Here comes the bastard now. The phrenology of his mountainous skull showed in contours through his military hair-cut. Erect and shining, his immaculate uniform hid a mess of ragged underwear.

'No, no, no,' said Mrs Angel Eels, 'we've had enough delays, we got to finish this partitioning — today!'

There was a murmur of approval. She glowed inwardly at their acceptance. She was a true daughter of the revolution, a tireless worker for the Party, sexually frustrated and slightly cross- eyed, the last two having something in common. At forty-one years of age, she now sat bolt upright, her black dress fastened high under her neck down to the floor, worn like a chastity armour that sealed her from all harm, and pleasure.

Hemjit

Protesting the border separating Catholics and Protestants, finding valid excuses for divorce, and how wily solicitors solve the problem of a person who has willed all his assets to himself after death.

Sunday. Father Rudden clutched the pulpit. He had said mass at such a speed, the congregation were thrown into great confusion, some were standing, others kneeling, some were leaving, the rest gave up and sat down. Skipping the sermon he launched into a secular attack on the new border. ‘If that border is to be permanent, it means that the Holy Catholic departed will forever be lying in British soil. Protestant soil, out there!!’ He pointed in the wrong direction and dropped his voice.

‘I should like for you who all feel strongly about this,’ he raised his voice ‘ and you’d better ,’ he crashed his fist down on the pulpit rail, splitting the wood and evicting a colony of woodlice; he lowered his voice, ‘sign the petition you will find hanging in the foyer.’ He stepped down, ‘Dominus vobiscum,’ he said, ‘Et cum spirito tuo,’ they replied. The verger counted the collection. ‘It’s a miracle how some of dese people’s clothes don’t fall off,’ he grumbled, extricating the buttons from the plate.

Three miles away Dr Goldstein pulled the sheet over the face of Dan Doonan. Mrs Doonan took the news dry-eyed. She’d only stayed with him for the money. Twenty years before she had tried to get a separation. The solicitor listened to her attentively. ‘But Mrs Doonan, just because you don’t like him, that’s no grounds for separation.’

‘Well, make a few suggestions,’ she said. ‘Has he ever struck you?’

‘No. I’d kill him if he did.’

‘Has he ever been cruel to the children?’

‘Never.’

‘Ever left you short of money, then?’

‘No, every Friday on the nail.’

‘I see.’ The solicitor pondered. ‘Ah, wait, think hard now, Mrs Doonan, has he ever been unfaithful to you?’

Her face lit up. ‘By God, I tink we got him there, I know for sure he wasn’t the father of me last child!’ The solicitor had advised her accordingly. ‘Get out of my office,’ he told her and charged six and eight-pence for the advice.

Now Dan was dead. ‘I wonder how much he’s left me,’ the widow wondered. Money couldn’t buy friends but you got a better class of enemy.

Messrs Quock, Murdle, Protts and Frigg, solicitors and Commissioners for Oaths, pondered dustily over the grey will papers; at 98, Dan Doonan had died leaving all his money to himself. The quartet of partners shook their heads, releasing little showers of legal dandruff. They had thumbed carefully through the 3,000 pages of Morell on Unorthodox Wills , and no light was cast on the problem. Murdle took a delicate silver Georgian snuff box from his waistcoat, dusted the back of his hand with the fragrant mixture of Sandalwood and ground Sobrani, sniffed into each nostril, then blew a great clarion blast into a crisp white handkerchief.

‘This will take years of work to unravel,’ he told his companions; ‘we must make sure of that,’ he added with a sly smile, wink, and a finger on the nose. They were, after all, a reputable firm built up on impeccable business principles, carefully doctored books and sound tax avoidance.

Only the last paragraph of the said will was clear. Doonan wanted a hundred pounds spent on a grand ‘Wake’ in honour of himself. Senior partner, Mr Protts, stood up, drew a gold engraved pocket watch to his hand, snapped it closed, ‘4.32 exactly, gentlemen – Time for Popeye,’ he said switching on the T.V.

Kavita

The experiences of a Chinese immigrant trying to find work in Dublin.

Ah Pong of Peking, China, had arrived in Dublin on a tramp steamer The General Gordon, engaged in smuggling monkeys from India to Tilbury. The Scottish Captain Gordon MacThun had lost his way many times before. Last year he set course for Madras and arrived at Elba. As Ah Pong remarked, 'Scotsman doesn't know his Madras from his Elba.' The little Chinese had done the trip to escape the stark poverty of China and was soon happily walking in the stark poverty of Ireland. He had jumped ship in Dublin with his worldly fortune of twelve pounds in yens. The money was pre-Czarist and was in several stages of devaluation at the same time. It took a Dublin bank clerk eighteen hours and two mental breakdowns to work out the exchange. Ah Pong came out with a smile and asked the first stranger:

'Hello General Gordon, where China Town?'

Not having one, the Dubliner thought the next best thing would be the Jewish quarter. He took Ah Pong to Frogg Street and pointed to a sign 'Bed and Breakfast for hire.' A large woman opened a small door.

'You want a room?' Mrs Goldberg asked.

'Please, I not make English much, hello — I come lite out Peking. Oh hello — General Gordon. Me.'

'I don't know what he's sayin',' she shouted back down the passage. 'I think its General Gordon,' she added.

'Wot is it?' Mr Goldberg came blinking- shuffling up the corridor. 'Oh,' he saw Ah Pong. 'He's all right, he's a Foreigner, they eat anything. Come in, come in.' He made a friendly gesture with the Dublin Jewish Chronicle. 'You a tourist then?'

'Me Chinee.'

'Oh, you a Chinee? Well, well. We live and learn, eh? Hows Sun Yat Sen gettin' on?'

'Cup of tea, Mr Chinese?' asked Mrs Goldberg, removing the cost.

Ah Pong made a sign in mime that he wished a bed for the night, lying on the floor and placing his hands along his head.

'See that, Rachel,' said the enlightened Mr Goldberg, 'Chinese drink it lying down.'

A puzzled Chinee watched as both Goldbergs took his tea stretched on the floor. Lodgers were hard to come by, and at all costs to be encouraged. A true son of the Orient, Ah Pong carried his customs with him. The Chinese New Year came. 'Happy New Year,' he shouted to a tram full of puzzled Dubliners and was bodily hurled off. For weeks he had searched for employment. His little store of money soon dwindled. One day he told the Goldbergs, 'Hello. Goodbye. Me I money all gone. No work here for Chinee. I bugger off, General Gordon.'

The Goldbergs had grown very fond of the little man. He paid his rent on the dot and didn't mind chickens in his bedroom. Mr Goldberg remembered the new Republic was desperately short of policemen. They had advertised the fact in The Sligo Clarion — 'Men of good physique over 4 ft 3 ins. will find a good life in the new Irish Free State Police Force.'

Gopa

Candid photography of women, and arranging to have a man with ‘leg trouble right up to his neck’ captured on camera

Arthur Manuel Faddigan hummed 'The Rose of Tralee', screwed the top of his pile ointment, and pulled up his trousers. The photographic trade in Ireland had been hard hit since the migration to America. Only the mad Mrs Bridie Chandler from the great ruined farm on the moor ever sat for him. Once a week she came galloping up, a great mountain of fat astride a black stallion; sweeping into the studio she'd strip off her clothes and shout 'Take me!' The first time had been shock enough. Faddigan had run all the way to church.

'Father,' he gasped, 'is it wrong to look at naked women?'

'Of course it is,' said Rudden, 'otherwise we'd all be doing it.' He had finally given Faddigan a dispensation to photograph her, providing he kept at a respectable distance.

Faddigan never did work out how much that was in feet and inches, and he never did comprehend 'How a woman could spread out in so many directions at once and still stay in the same place.'

His wife arrived one day when he was printing the negatives and beat him silly with a bottle of best developing fluid at 23 shillings a pint. 'You dirty pornographer,' she said, and left him for good. The small green shop bell tinkled briefly, and in came three men with the dangling Dan Doonan.

'Is he drunk?' inquired Mr Faddigan.

'No, no,' said one of Dan's supporters, 'he's got leg trouble.'

'What's his head hangin' down for?'

'He's got leg trouble right up to his neck.'

'Oh. Just sit him in the chair.' Doonan slid to the floor. 'Ups-a-daisy,' said Faddigan kindly.

'We want passport photos.'

'Is he going away then?'

'Yes.'

'Where to?'

'We're not sure, but he's got a choice of two places.'

'Just hold him like that, I can see he's an old man. Smileeee. ... There, that's it. If he's pleased with the result, perhaps he'll come again.'

'Oh, he'll never be that pleased,' said the departing trio. And they carried dear Dan away.

Geetha Joseph

About the escape of a panther from the circus and its recapture

GULIO CAESAR presents The World's Finest Animal Circus. The words were painted six foot high in modest black and white. Circus master Gulio Caesar, 'King of the Ring', was a worried man. Constantly at war with fleas that continually transferred their allegiance from the monkeys to him, he slept with a tin of Keatings by his bed. At midnight he awoke scratching and cussing, when through his caravan window he made the awful discovery. The cage was open and the beast had gone. Scratching with one hand and dialling with the other, he phoned the R.S.P.C.A.

Awakening from his veterinary slumbers, Inspector Felix Wretch groped in the dark for the jangling instrument.

'Hello?'

'This is a — Gulio Caesar, could I please spik wid your husband?'

'Me husband speaking,' said Mr Wretch.

'Gooda, one of my black-a panthers has escape.'

Mr Wretch gulped himself into consciousness. 'I'll meet you outside the police station right away in ten minutes.' 'Right,' the line clicked to immutability.

Hurriedly Mr Wretch pocketed a humane killer, a phial of liquid and a hypodermic, then stepped into his trousers and into the night.

Into the wood along the river bank stumbled five happy drunks. Suddenly Rafferty stopped. 'Shhh, there's something in me trap,' he said excitedly. The information silenced the singing. Cautiously they approached towards a black sleek shape crouching on the ground. 'It's a —' commenced Rafferty, but was cut short by a scarlet mouth emitting an unusually loud growl.

'No, it isn't,' he concluded.

'It isn't what?' queried O'Brien.

'It isn't what I thought it was at first.'

'It should,' went on Rafferty, peering at the creature, 'it should be a fox.' The creature repeated a growl loud enough to stop the five in their tracks. What it was they knew not, that it was very big they knew, but what type of big they also knew not.

Pamela

Ordering a coffin with ‘post mortem mensuration’

Life is a long agonized illness only curable by death. Ruben Croucher lovingly and delicately dusted the coffins displayed in his parlour. They were such beautiful things. Stately barques that bore us across the Styx into the eternal life beyond. All was peace and calm within. The only sound was the endless buzzing of a lone fly, whoshall remain nameless. Ruben Croucher walked with crane-like dignity across the black cracking lino to the window. His long thin nose pointed the way; a million rivers of tiny ruptured veins suffused his cadaverous face, two watery eyes like fresh cracked eggs in lard looked out from a skull- like head. It had got dark early and he had lit the gas, which cast a sepulchral glow along the neatly arranged coffins. With a cloth he wiped the condensation from the sightless windows. Business was bad, it seemed people couldn't afford to die these days. But, what was this?

Two ragged-arsed men were approaching, both smoking the same cigarette. They were pulling a cart and heading rapidly for the shop. Pausing only to open the door, they entered. When Lenny saw the face of Mr Croucher, he reverently took his hat off. Croucher bowed ever so slightly from the waist up.

'Good morning,' he said, then after some thought added, 'Gentlemen.' After all they could be eccentric millionaires.

Shamus coughed. 'We are eccentric millionaires,' he said. 'Do you sell coffins?'

Mr Croucher nodded. 'Yes, we do, sir,' and as a try on, 'how many do you want?'

'Oh, just one to start with.'

'Good, good. Who is the deceased?'

'Oh.' Shamus hadn't thought of this, but he was a man of some guile. 'It's for me friend here,' and he pointed at Lenny. 'You see,' he went on, 'he hasn't been well lately, and we thought just to be on the safe side we'd have one now.' Mr Croucher, though puzzled, pressed on. 'Ahem. Well, I suppose this method will save normal post mortem mensuration.'

‘Eh?’

‘Measuring him. Now he can — well — try one for size.' Mr Croucher indicated the coffins. Shamus and Lenny ran their hands over several.

'We'll have that one.' Shamus pointed. 'Ah, a black one. A very wise choice, sir, it won't show the dirt.' Mr Croucher withheld a whimper of joy. It was the most expensive coffin in the shop.

Lenny slid over the side and lay back in the pink satin padding.

'It feels real fine!' he said. 'Dis is really worth dying for.' He squirmed to make himself more comfortable.

'Now let's try the lid on,' said Mr Croucher.

Carefully he lowered the lid over Lenny's little white face. Shamus raised his voice.

'Hows dat feel, Lenny?' 'Very nice,' came the muffled reply. 'Right,' said Shamus addressing Mr Croucher. 'We'll have this one.'

Ruben rubbed his hands with professional pleasure, the dry skin crackling like parchment. Forty years he had sold coffins, but never as quickly as this. His father, the late Hercules Croucher, O.B.E., had founded a fine parlour at Shoreditch. King Edward the Seventh and his ten mistresses were on the throne when the young Ruben was given a black suit for his tenth birthday, that and a scale model replica of the famous Geinsweil Coffin. It awakened in him some deep-rooted instinct; he buried it. Other boys felt girls and played conkers, but little Ruben watched local workmen digging, digging, digging.

'Now sir,' Ruben said, 'if you will step into the office we'll conclude the financial side.'

'You stay there a while,' said Shamus rapping on Lenny's coffin. In a small room at the back Mr Croucher slid behind an order book and perched on a fountain pen. His black tail coat hung from his shoulders like tired wings. Neatly he took down details in his book. All was silent save the scritch-scratch of his Waverley nib on ruled foolscap.

A great pot of steaming hot Irish stew was heading for the shop at seven miles an hour. It was carried lovingly in the hands of Mrs Ruben Croucher, ex-shot-put champion of Ireland. She walked with a brisk bouncing athletic step, a step forty years younger than her husband's. It had been a most successful marriage. He couldn't do it, and she didn't want to. They had one child. He didn't take after either of them. He did it all the time and walked with a stick. Into the shop bounded the ex-shot-put champion.

'Coooooooeeeee! Are you in there, darling?' The lid of Lenny's coffin rose up. 'Hello, little darlin' said Lenny cheerfully.

An Irish stew struck him between the eyes. Mrs Croucher ran screaming from the shop.

'There's your receipt, sir,' said Mr Croucher after carefully counting and recounting thirty- eight carefully forged pound notes.

'We'll take the coffin back on our cart,' said Shamus, standing up.

The culinary arts of the world are varied and a blessing to the sensitive innards of the gourmet, but never in his tour of the globe had Mr Croucher seen a man in a coffin, unconscious and covered in Irish stew.

Saras

TNT is extracted from a coffin and ‘the power of de author’ comes into play

The heavy metal cutters minced through the barbed wire. O'Brien had cut close to the wooden posts. Father Rudden at his side gave the thumbs up sign. Through the gap, the five men crawled towards the grave of Dan Doonan, rapidly becoming the most travelled corpse in Ireland. Milligan, in the van, cast anxious eyes towards the sentry three hundred yards to their left. A light from the guard hut glinted on the soldier's bayonet. The five men moved to the temporary shelter of an ancient mulberry. Only one hour before two ragged-arsed men had hid in the self- same place. They too had felt for the grave with the loose earth. Soon they were digging up the coffin of Dan Doonan.

'Strange dis T.N.T. doesn't feel so heavy now,' said Shamus.

'No, it doesn't,' said Lenny struggling manfully alone under the weight of the coffin.

Father Rudden led his men forward, his hand too felt for a grave with loose earth.

'Funny, I could have sworn it was over there,' said the Milligan as the shovels set to work. Soon the coffin of 'Mrs Eileen Spoleen' with its 200 lb. of T.N.T. was rising. '

Freeze!' said Goldstein.

The party stood, knelt and lay transfixed as a soldier came suspiciously forward. He held his rifle at the ready, he came closer. He stopped, looked cautiously left and right, placed his rifle against a tree. ... The dirty swine! No wonder the place was starting to smell. They heaved on ropes, sweat was pouring down Milligan's arms.

'Freeze!'

The bloody sentry was coming back; the diggers, gasping, lay flat and still, the ropes cutting their hands.

'Anybody out there?' called the soldier. 'If there's anyone out there say so and I'll fire.' He raised his rifle.

Milligan looked imploringly out of the page.

'For God's sake don't let him shoot, Mister.' The soldier about-turned and marched away. Milligan grinned.

'God, you got all the power in this book.' He stroked the stubble on his chin. 'You havin' the power of de author, can I have a request?'

'Yes.'

'Dat dirty soldier that nearly pissed on us, make him do something that will get him into trouble.'

The soldier returned to his post, sloped arms, fired three rounds in the air, dropped his trousers and sang Ave Maria. The Sgt of the Guard came hurrying from his tent.

'Private Worms?' he shouted, 'You're under arrest.'

A powerhouse raspberry was the reply.

'What's going on here?' said Lt Walker, arriving pyjama-clad on the scene.

'I'll show you, sir,' said the sergeant, and inexplicably launched into a series of cartwheels, back somersaults and impressions of Al Jolson in Maltese.

'Both under arrest for being drunk and disorderly. Turn out the guard.'

At the command, the guard assembled and watched him, the Lieutenant, return to his tent with a series of animal noises and great backward leaps on one leg. What would his father Field Marshal Walker, M.C. and Bar, say? Nothing; at this self-same moment he was performing the same feats before his puzzled sovereign at the Passing Out Parade at Sandhurst.

Milligan watched the Lieutenant's antics with a great piano-keyboard smile.

'By Gor, you got the power all right. I wish I was a writer.'

Priya

Colonic irrigation and enemas end in a BOOM! and up goes the Count, and the Castle and all

Chapter 10, (p110) The count Fritz Von Krappenaser had fled to……(p113) his wish had come true

The Count Fritz Von Krappenhauser had fled to Northern Ireland, bought Callarry Castle, ten thousand acres, and a small packet of figs. For years he brooded over the loss of the ancestral abort. Finally worn out by indifferent, and severe wood-seated Victorian commodes, he decided to build a replica of the family's lost masterpiece here in the heart of Ulster's rolling countryside. He employed the greatest baroque and Rococo architects and craftsmen of the day, and every day after; seven years of intense labour, and there it now stood, a great octagonal Easence. No ordinary palace was this; from the early stone Easence of Bodiam Castle to the low silent suite at the Dorchester is a long strain, but nothing equalled this, its gold leaf and lapis lazuli settings gleaming in the morning sun, on the eight-sided walls great ikons of straining ancestors, a warning to the unfit. Through a Moorish arch of latticed stone, one entered the 'Throne Room'; above it, in Gothic capitals the family motto, 'Abort in Luxus'. From the centre rose a delicate gilded metal and pink alabaster commode. Six steps cut in black Cararra marble engraved with royal mottoes led up to the mighty Easence; it was a riot of carefully engraved figurines in the voluptuous Alexandrian style, depicting the history of the family with myriad complex designs and sectionalized stomachs in various stages of compression. The seat was covered in heavy wine damask velvet, the family coat of arms sewn petit-point around the rim in fine gold thread. Inside the pan were low relief sculptures of the family enemies, staring white-faced in expectation. Towering at the four corners, holding a silk tasselled replica of the Bernini canopy, were four royal beasts, their snarling jaws containing ashtrays and matches. Bolted to the throne were ivory straining bars carved with monkeys and cunningly set at convenient angles; around the base ran a small bubbling perfumed brook whose water welled from an ice-cool underground stream. Gushes of warm air passed up the trouser legs of the sitter, the pressure controlled by a gilt handle. By pedalling hard with two foot-levers the whole throne could be raised ten feet to allow the sitter a long drop; and even greater delight, the whole Easence was mounted on ball-bearings. A control valve shaped like the crown of Hungary would release steam power that would revolve the commode. There had been a time when the Count had aborted revolving at sixty miles an hour and been given a medal by the Pope.

White leather straps enabled him to secure himself firmly during the body-shaking horrors of constipation. Close at hand were three burnished hunting horns of varying lengths. Each one had a deep significant meaning. The small one when blown told the waiting household all was well, and the morning mission accomplished. The middle one of silver and brass was blown to signify that there might be a delay. The third one, a great Tibetan Hill Horn, was blown in dire emergency; it meant a failure and waiting retainers would rush to the relief of the Count, with trays of steaming fresh enemas ready to be plunged into action on their mission of mercy and relief. With the coming of the jet age the noble Count had added to the abort throne an ejector mechanism. Should there ever be need he could. whilst still in throes, pull a lever and be shot three hundred feet up to float gently down on a parachute. The stained glass windows when open looked out on to 500 acres of the finest grouse shooting moor in Ulster. He had once invited Winston Churchill to come and shoot from the sitting position. In reply Churchill sent a brief note, 'Sorry, I have business elsewhere that day.' From his commode, the Count could select any one of a number of fine fowling pieces and bring down his dinner. Alas, this caused his undoing. The boxes of 12-bore cartridges, though bought at the best shops in London, had sprung a powder leak. Carelessly flicking an early morning cigar, the hot ash had perforated the wad of a cartridge.

But to the day of the calamitous fire. It had been a fine morning that day in 1873. The Count had just received his early morning enema of soap suds and spice at body heat; crying 'Nitchevo!' he leapt from his couch. Colonic irrigation and enemas had made his exile one internal holiday. Clutching a month-old copy of Der Tag, and contracting his abdomen, he trod majestically towards his famed Imperial outdoor abort bar. A few moments later the waiting retainers heard a shattering roar and were deluged, among other things, with rubble. 'Himmel? Hermann? What did you put in the last enema?' queried the family doctor of the retainers.

Flames and debris showered the grounds and there, floating down on the parachute, came the Count. 'People will look to me when I die,' he had once said. His wish had come true.

No comments:

Post a Comment