For this poetry session Joe initiated the Zoom session from Arlington, MA, proof that Zoom no distinction makes of geography, so long as the clients are connected to the Internet.

Devika remarked that KumKum looked very relaxed – it makes such a huge difference not having to run a household.

J&K used to go to USA to visit the children and grandchildren every summer, but they were last there in 2019 – 2020 was entirely lost to Covid-19. Devika’s niece left Shanghai at that time and came to India because the disease was raging in China at the time.

Arun drinking tea from a rooster mug

The mug is from the Oxford Natural History Museum. Devika buys a mug from shops when she goes on foreign visits and showed a tea mug she got from Kenya:

Devika shows her mug from Kenya

She has one from a museum in Cape Town and one from thee museum of Antoni Gaudí in Barcelona. His work is very colourful, perhaps could be labeled gaudy …

We were expecting to hear from Thommo and Geetha who are singing two Dylan songs; Thommo sent in the songs recorded ahead of time so as as to avoid glitches on the Internet during the Zoom. Geetha is sporting a short haircut that Devika liked. Arundhaty said KumKum looks quite chilled out and younger. Lots of pampering goes on in Arlington at Rachel’s home – even washing clothes in the machine and folding is taken care of! The children who work from home require quiet. J&K who are accustomed to being noisy (Bongs are like that, said Arundhaty) have to compose themselves.

KumKum mentioned enjoying food from a Punjabi restaurant in Arlington and her mind wandered to the food from Fusion Bay restaurant in Fort Kochi. Regularly ordering from them helps to keep their workers employed – it’s a good variety of Kerala food they serve. The young men are gradates from a food institute in Kerala and now they are all married but continue to make their tasty dishes which they sell at moderate prices.

The novel next month, Joyce Carey's The Horse's Mouth, will be read on July 30. Arundhaty has started reading it. She likes it quite a bit and Devika said Gulley Jimson, the artist, is a real bindaas character. The movie is there on YouTube – Alec Guinness stars in the role of Gulley Jimson. He is an actor who could take on any character, tragic or comic, and do the part as if he was made for it, said KumKum. The novel itself has a link from which you can download it free. Register for a free account on archive.org and go to

https://archive.org/details/horsesmouth00cary/page/n9/mode/2up

to read The Horse's Mouth online. .

Hydrangeas in Rachel's garden

The hydrangeas in Rachel’s garden are in good condition – they do not seem to do as well in Kochi said Devika and Arundhaty agreed they need the cooler weather of our hill stations such as Kodaikanal and Coonoor. In Kochi the colours look a bit faded.

KRG Poetry Session, June 25, 2021 – Full Account and Record

Three members will be missing today: Zakia is busy with her son’s nikah. Namrata, Kavita’s daughter is going to be married soon, which keeps Kavita busy.

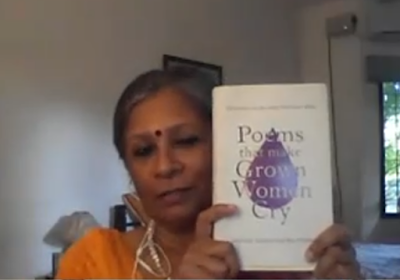

Devika held up the book she got as a prize (the book award supported by J&K’s children), Poems That Make Grown Women Cry. She wanted to have her thanks conveyed to them.

At the last poetry session too she got the poem by Simon Barker from the same book.

KumKum wanted to throw up a challenge for this December’s fancy dress to go one better than last year’ winners – Arundhaty & Devika. She will dress up Pamela and Pamela will do the facial makeup for her.

Our guest from TVM, former member Talitha, appeared and Joe offered she could go first instead of at the end.

Talitha

Her poem is by Ezra Pound and is labelled as ‘After Li Po’, meaning it is not a direct translation but a poem that was inspired by one of Li Po’s poems. Li Po is now generally known as Li Bai; see

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Li_Bai

He is one of the well-known Tang Dynasty poets who belongs to the 8th century CE. Here is the only surviving manuscript in his hand:

Li Bai – The only surviving calligraphy in Li Bai's own handwriting, titled Shangyangtai (To Yangtai Temple), located at the Palace Museum in Beijing, China

Li Bai and his friend Du Fu (712–770) were the two prominent poets in the Tang dynasty era, which is often referred to as the ‘Golden Age of Chinese Poetry.’

In the poem The River-Merchant’s Wife the bride who came as a bashful girl to her husband’s house felt homesick but soon she grows in devotion to her lord and says:

I desired my dust to be mingled with yours

Forever and forever, and forever.

Her husband has been gone a long while on his business and as the young wife waits she can only think every day of him but can’t go forth. She bids him send word when he will come so she can come to greet him, as far as the town of Chō-fū-Sa. She feels his absence. Talitha said it was a child marriage and the wife is feeling her way into the relationship. Earlier her husband was just a playfellow. She is transferring her feelings to the monkeys as Talitha pointed out:

And you have been gone five months.

The monkeys make sorrowful noise overhead.

At fourteen I married My Lord you.

…

At fifteen I stopped scowling,

How young! But Talitha remarked Juliet was the same age fourteen.

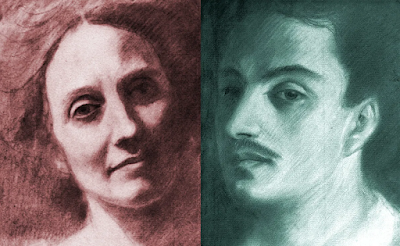

Talitha then read something about Ezra Pound, prefacing it by saying the more she read about him the worse he came off as a person. However, the poem stands on its own. Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an expatriate American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a fascist collaborator in Italy during World War II.

His works include Ripostes (1912), Hugh Selwyn Mauberley (1920), and his 800-page epic poem, The Cantos (c. 1917–1962).

Ezra Pound photographed as a young man in 1913 by Alvin Langdon Coburn

Pound's contribution to poetry began in the early 20th century with his role in developing Imagism, a movement stressing precision and economy of language. He helped discover and shape the work of contemporaries such as T. S. Eliot (on whom he had a major effect, in shaping The Waste Land), Ernest Hemingway, and James Joyce. It is remarkable that these poets had distinctly different styles, yet were influenced by one and the same critic. Hemingway wrote in 1932 that, for poets born in the late 19th or early 20th century, not to be influenced by Pound would be like passing through a great blizzard and not feeling its cold.

Pound moved to Italy in 1924, embraced Benito Mussolini's fascism, and expressed support for Adolf Hitler. During World War II and the Holocaust in Italy, he made hundreds of paid radio broadcasts for the Italian government, attacking the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt and, above all, Jews, as a result of which he was arrested in 1945 by American forces in Italy, on charges of treason. He spent months in a U.S. military camp in Pisa and was incarcerated in a psychiatric hospital in Washington, D.C., for over 12 years.

While in custody in Italy, Pound began work on sections of The Cantos that were published as The Pisan Cantos (1948), for which he was awarded the Bollingen Prize for Poetry in 1949 by the Library of Congress, causing enormous controversy. After a campaign by his fellow writers, he was released from the psychiatric hospital in 1958 and lived in Italy until his death in 1972. From his Italian exile he labeled America as an insane asylum. His political views have ensured that his life and work remain controversial.

Joe said as a critic and editor of poets he had significant influence because he delved deep into what poets wrote, and came up with improvements, which in the case of T.S. Eliot included ripping out large sections of The Waste Land. Poets approached him because of his genuine ability and he wasn’t somebody to pat you on the back and say ‘good show’ but would sit down and seriously read and edit the work poets submitted. The Bollingen Prize far exceeds any Pulitzer in stature as far a Poetry is concerned. That he espoused fascism and held a deep-seated anti-Jewish bias was no doubt reprehensible, but others like P.G. Wodehouse have been led astray to a lesser degree. You can read about Pound and the insanity defence by which his lawyer which got him out, in the article Coming to terms with Ezra Pound’s politics by Evan Kindley:

https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/coming-to-terms-with-ezra-pounds-politics/

Ezra Pound – the Insanity Defence

Arundhaty

Academic books by Nair include Technobrat: Culture in a Cybernetic Classroom (Harper Collins, 1997); Narrative Gravity: Conversation, Cognition, Culture (Oxford University Press, 2003); and several other volumes. Nair serves on the editorial boards of several International Journals. In addition, she writes in major national dailies and magazines and is a frequent TV panellist.

Devika

Not much about Imtiaz Dharker has been written to go into her bio. But there is a barebones video about her put up by an Indian chap. Nothing about her parents or siblings. She was born in Pakistan, moved to Scotland when she was a year old. She eloped and came to India and married Anil Dharker, later divorced him, and went back to England. Most of her time is between London and India. She has a daughter, Ayesha Dharker, who is an actress. Her poems also show the effect of cultural displacement, stemming from her mixed heritage. The poem chosen is called Minority and may have its origin in her experience of how she was treated as a person from another culture when she lived in Glasgow, Scotland. Her poem is about feeling rejection and how literature can be a means of restoring balance. Inherited tastes in food makes for a crossover on occasions, for example, taking sandwiches and chicken tikka on a picnic. The poem expresses the author’s belief in literature to break through barriers when you don’t seem to fit:

I don’t fit,

like a clumsily translated poem;

Imtiaz Dharker thinks of writing a poem as if penetrating a dense layer of skin to get to what’s underneath:

And so I scratch, scratch

through the night, at this

growing scab on black and white.

…

to infiltrate a piece of paper.

Imtiaz Dharker

She hopes the lines she writes will may their way into the heads of her readers, and so they may ultimately realise and recognise her as one of their own, not a foreigner. Gopa pointed out that in the late sixties Britishers were not welcoming to outsiders of any kind. When she went to Pakistan she was an outsider there too. Thommo spoke about a colleague in India, David, who married a Danish woman, and in 2008 went back to UK. In India they played bridge every day at the Cochin Club. When he met them in England Thommo asked if they played bridge back still, and David answered that his wife Anne Marie was not accepted at the club and so he stopped going. It was a small coastal town, Weymouth, and they didn’t like foreigners, even the Welsh. Joe laughed, joking that the Welsh may soon indeed be foreigners, for the UK is feeling the internal pressures of Brexit and may break apart over time. Devika mentioned a hoarding she saw in Scotland at a petrol bunk – she didn’t remember the exact words but it was beautifully written. There’s a protest that God has given everything to Scotland: mountains, craggy coasts, beauty, water, etc. God replies: but look who I have given them as neighbours! Everyone laughed …

(Click to expand)

God replies when the angel Gabriel protests about his generous gifts to Scotland – wait till you see the neighbours I've given them

Joe said that in spite of the discrimination that persists in USA, and perhaps to a greater extent in UK – at the highest levels they do recognise merit when they see it. Gopa demurred saying that the English (not the Welsh or the Scots) think they are superior and no one else makes the cut, no matter what you may have studied or accomplished. They recognise the St George’s Cross of England flag more than the Union Jack. If they accept you, as she was accepted by the school where she taught, they will give you a George’s Cross hat when you are leaving; for which she thanked them, and said bye.

But isn’t Imtiaz Dharker a recognised poet in the UK? – asked Joe. Yes, she is even in the GCSE school curriculum said Devika, and Gopa confirmed. That’s what Joe meant. As another example, the India-born Nobel laureate Sir Venkatraman Ramakrishnan was elected the president of the prestigious Royal Society in the UK in 2015. Geeta agreed and said it is the people with whom you associate that matters rather than whether they belong to one or the other among the nations comprising the UK. Joe said the St George’s Cross unfortunately has become the flag of the rowdyism displayed by England fans on football pitches, to the point of their being banned:

https://www.history.com/.amp/this-day-in-history/english-football-clubs-banned-from-europe

The recent Euro 200 UEFA Cup Final gave another example of the hooliganism that accompanies England football fans. They stormed into the Wembley stadium in numbers far greater than the tickets sold, and thronged with no fear of Covid-19. The police were missing. The morning after they gave a full-on display of racism against black players like Rashford, and the rookie, Bukayo Saka, who missed the fifth penalty. As The Guardian reported “… it was drowning town centres in seas of debris, filling A&E departments with the victims of senseless punch-ups, defacing murals, and then blaming it all on people who look different …”

Gopa added that it is this plebeian class of people, not the educated intelligentsia, who support the monarchy. It was a lively discussion.

Geeta

On Friendship a poem by Kahlil Gibran.

Pamela has the book; it’s lovely, beautiful, she said. When Geeta finished reading Joe said the book must be one of the most widely sold books of wisdom in the world. It was customary to give it as a gift on birthdays, said Pamela, and Joe attended a wedding once of new-age couple in the nineties where an excerpt from The Prophet was the main reading. Couples used to read aloud from the book at barefoot weddings (“Love one another but make not a bond of love, let it rather be a moving sea between the shores of your souls”). Other well-known dicta are these:

“Your children are not your children, they are the sons and daughters of life’s longing for itself,”

“Work is love made visible,”

KumKum said it was very popular in our youth, but the fashion has waned, and nobody would gift the book today. Why is that so asked Geeta? Perhaps the leading traits of The Prophet – idealism, vagueness, sentimentality – do not appeal at the moment, but a new generation may rediscover it.

Joe said the style in which it is written encourages a way of speaking as though deep wisdom is being delivered in vague statements with something startling at its core. One of Joe’s cousins is fond of making such aphoristic wisdom-sounding statements, so Joe tells him: Endhanu, oru Gibran adikiyano?

Gibran emigrated with his parents to Boston in 1895 after primary schooling in Lebanon. He returned there in 1898 and studied in Beirut, where he excelled in the Arabic language. He published his first essays after returning to Boston in 1903. In 1907 he met Mary Haskell, who became his lifetime benefactor and funded his art study in Paris. Gibran settled in New York City thereafter in 1912 and devoted himself to writing the sort of literary essays and short stories which made him famous. He wrote both in Arabic and English, and also pursued painting.

Gibran’s literary and artistic output is romantic in outlook, liberal in thought, and emphasises independence. He was influenced by the Bible, Friedrich Nietzsche, and William Blake. His writings deal with themes such as love, death, nature, and a longing for the homeland. They are lyrical in nature, expressive of Gibran’s deeply religious and mystic nature.

The Prophet, a book of 26 poetic essays by Kahlil Gibran, was published in 1923. It became a best-selling book of popular mysticism, and was translated into more than a dozen languages. More than a hundred million copies have been sold. Although many critics thought Gibran’s poetry mediocre, The Prophet achieved cult status among American youth which lasted for several generations, and continues. The Prophet is about a man who sets sail for home after an exile of 12 years, when he is requested by the citizens to speak to them about the mysteries of life. He does so, discussing love, marriage, beauty, reason and passion, and death, among other topics.

Sales of The Prophet have been a cash cow for Alfred A. Knopf, the publisher; in the sixties the royalties on Gibran’s books amounted to $300,000 a year. But Gibran was never a favourite of the critics. Two biographies have been written, the first in 1974, 43 years after his death, titled Kahlil Gibran: His Life and World by a cousin of the poet also named Gibran. The second was in 1998, the more investigative Prophet: The Life and Times of Kahlil Gibran.

Gibran’s principal works in Arabic are: ʿArāʾis al-Murūj (1910; Nymphs of the Valley); Damʿah wa Ibtisāmah (1914; A Tear and a Smile); Al-Arwāḥ al-Mutamarridah (1920; Spirits Rebellious); Al-Ajniḥah al-Mutakassirah (1922; The Broken Wings); Al-ʿAwāṣif (1923; “The Storms”); and Al-Mawākib (1923; The Procession), poems. His principal works in English are The Madman (1918), The Forerunner (1920), The Prophet (1923; film 2014), Sand and Foam (1926), and Jesus, the Son of Man (1928).

Shakespeare, we are told, is the best-selling poet of all time. Nowadays Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi is a close second. They say Lao-tzu is up there too. Kahlil Gibran is surely among the most widely read in the twentieth century, and he owes his place on that list to this one book, The Prophet.

As New Yorker critic Joan Acocella states “The Prophet is quoted in books and articles on a variety of subjects. Words excerpted rom it turn up in advertisements for marriage counsellors, chiropractors, learning-disabilities specialists, and face cream.”

Gibran wrote seventeen books, nine in Arabic and eight in English.

His mother Kamileh indulged him as he grew up with 3 siblings in Lebanon, of whom two died young, and one sister, Marianna, survived Gibran and followed him throughout his life in America.

Gibran’s father was neither well-to-do nor a hard worker. He was lazy and given to drink. Later he was prosecuted for embezzlement. In 1895, Kamileh packed up her four children – Bhutros, Kahlil (then twelve), Marianna, and Sultana and sailed to America. They settled in Boston, in the South End, a ghetto filled with immigrants from various countries. Kahlil went to school there, for the first time.

He also enrolled in an art class and was sent to a man called Fred Holland Day, who curiously wore a turban and smoked a hookah, but did serious work. He took photos of children and the one below shows an arty photograph of Gibran in his teens. Day introduced him to the literature of the nineteenth century, the Romantic poets and the Symbolists. Day made a fuss over Gibran’s Middle Eastern origins, and treated him like a princeling – Gibran looked the part.

While his mother and two siblings died, his sister Marianna remained. She adored him, cooked his dinners, made his clothes, and supported the two of them.

Day held an exhibition of Gibran’s drawings in his studio in 1904. Gibran also began publishing his writings: stories and poems, in his typical aphoristic form. At this point Mary Haskell, the headmistress of a girls’ school in Boston, entered his life. Gibran became close to Haskell, in 1908. Haskell was older than him by nine years. She was not rich, but she managed to put aside enough money to support deserving causes, of which Gibran was her most worthy one.

https://www.brainpickings.org/2017/01/20/kahlil-gibran-mary-haskell-love-letters/

Gibran was sure that a great destiny awaited him. She continued to educate him in English, using the classic authors. Gibran left Boston and moved to New York in a studio apartment for which Haskell paid the rent.

Gibran made a serious decision to stop writing in Arabic and begin writing in English. His great enabler for this project was Mary Haskell who became his full-time editor. He sent her his manuscripts, and she sent back voluminous corrections. He dictated his work to her. Sometimes he gave the ideas and it was she who found the phrases to set them in English. In 1926 Haskell married a rich relative of hers, knowing Gibran would not object. But at night, after her husband went to bed, she would work on Gibran’s manuscripts. She edited all his English-language books. The third of them was the future gold mine, The Prophet.

In the introductory frame we are told Almustafa, a holy man, has been living in exile, in a city called Orphalese, for twelve years. But now he is going back to the island of his birth. When the citizens ask him to leave them a memorial of his life, he pours forth his advice concerning love, suffering, the need for children to become independent and so on. It was an advice book, inspirational in nature, a preview of all the twentieth century advice books. This ensured a substantial readership. The Prophet appeals not only by the seeming opposition of its ideas to conventional wisdom, but by its strange power to hold the reader transfixed (and content) by its oracular phraseology.

Gibran told Haskell that the whole meaning of the book was “You are far far greater than you know—and All is well.” There is another book by Gibran, Jesus, the Son of Man, which was published five years later. This is his second-most-popular work. It is not a book of advice or consolation but a novelistic collection of interviews with people remembering Christ. He drops the vatic tone of The Prophet.

After the publication of The Prophet, Gibran got tons of fan mail. He was also mobbed by (mostly female) acolytes, but did not enjoy these attentions. Though he was now making money, he didn’t change his monastic way of living in a one-room studio to the end of his life.

Acocella writes that when Gibran was in Paris, he met Rodin, and he later claimed that the famous sculptor had called him “the William Blake of the twentieth century.” This tribute was probably a concoction by Gibran, says Acocella.

By his forties, Gibran was a sick man. He became alcoholic. In his last years, he stayed alone in his apartment, mostly drinking arrack supplied by Marianna. In 1931 he was bedridden, and was taken to St. Vincent’s Hospital, where he died of cirrhosis of the liver.

Marianna took the body to Lebanon for burial, as Gibran had wished. Gibran stated that the money from royalties was to be spent on good causes. When a committee could not decide on the causes, Knopf started withholding the royalties. The Lebanese government intervened and, reportedly, eventually got Gibran’s estate properly administered. His coffin rests in an unused monastery called Mar Sarkis, in Bsharri.

[The above is based on a 2007 article by Joan Acocella in The New Yorker titled Prophet Motive: The Kahlil Gibran phenomenon. ]

Geetha/Thommo

Bob Dylan was born on May 24, 1941. His name was Robert Allen Zimmerman, but he took the name of Dylan because of the Welsh Poet Dylan Thomas. He’s easily the youngest 80-year old in the world said Thommo. His career spans 60 years and he’s been a major figure in the cultural sphere since the 1960s. Two of his politically charged songs Blowing In The Wind and The Times They Are A Changing became the anthems of the American Civil Rights and Vietnam Anti-War movements. It’s no wonder he’s regarded as one of the greatest song-writers of all time. Across the six decades of his career, the singer-songwriter has mined America’s past for images, characters, and events that speak to the nation’s turbulent present.

Bob Dylan in 1965

A keynote speaker, Sean Wilentz, in a lecture delivered at a conference to honour Bob Dylan’s eightieth birthday wrote:

Dylan has long populated his songs with historical characters, as well as characters from the territory where history shades into legend, and his work is never too far from the larger American mythos emanating from its rough and rowdy past, with its gamblers, prophets, false prophets, and outlaws, from Billy the Kid to Lenny Bruce (the comedian). In his 2004 memoir Chronicles, Dylan writes, convincingly, of reading deeply in history books once he’d reached Greenwich Village, and of how figures such as the antislavery and civil rights congressman Thaddeus Stevens, who had “a clubfoot like Byron,” made a deep and lasting impression on him.

Dylan used to tour extensively until a motorcycle accident in 1966 caused him to withdraw. In the late 1970s he became a born-again Christian. He released a number of contemporary gospel music albums before returning the more familiar rock rhythms in the 1980s. Thommo listened to one of the gospel songs in the morning; quite nice to hear.

He’s also an artist. In 1994 he has published 8 books of drawings and paintings and his work has been exhibited in major art galleries. He has sold more than 125 million records, and is thus one of the best selling musicians of all time. He’s received numerous awards including the U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom and 10 Grammy awards. The board of the Pulitzer Prizes awarded him a special prize in 2008 “For his profound impact on popular music and American culture, marked by lyrical compositions of extraordinary poetic power.”. His songs have won Golden Globe awards and Academy awards (Oscars) for the best original song. In 2016 Bob Dylan received the Nobel Prize in Literature “For having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition."

His approach has been simple even as he has essayed a multitude of songs and lyrics:

“If a song moves you, that's all that's important. I don't have to know what a song means. I've written all kinds of things into my songs. And I'm not going to worry about it – what it all means.”

Bob Dylan older

Thommo posed the question for readers: has anyone else had received both a Nobel and an Oscar? It’s George Bernard Shaw whose birthday (July 26) Thommo shares. GBS won the Oscar in 1938 for the best screen adaptation of Pygmalion. Dylan won the Oscar for the best original song in a movie called Wonder Boy. But Dylan is the only one to have won the Oscar, The Nobel Prize, and the Grammy (10 times).

Pamela said Bob Dylan has sung a song titled Sarah, which caused Oohs and Aahs to rise from the readers’ lips: Pamela Sarah John is her name.

Blowing In The Wind was written in 1962; it was first released as a single and then in the 1963 album The Freewheeling. It consist of a series of protest songs and poses a number of questions. It was used as an anthem in the Vietnam Anti-War movement taking off on the lines:

…how many times must the cannonballs fly

Before they're forever banned?

The answer, my friend, is blowin' in the wind

The answer is blowin' in the wind

It is oblique in its reference, for no foreign policy item is mentioned. It talks about people rather than individuals and indicates how war affects society. The first line:

How many roads must a man walk down

is taken from the science fiction novel The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (Chapter 32), a popular book at the time among young people. Here is the song Thommo and Geetha sang which you can click to play:

Thommo & Geetha – Blowin In The Wind

Everybody spontaneously clapped after listening to this song led by Geetha’s voice. Her brother helped them record it at his place.

The next one is sourced from Irish and Scottish ballads. It has a universal message and is coupled with great music: those who tend to dwell in the past must realise the times are changing and they need to change too. It was released in 1963 during theAmerican Civil Rights Movement led by the young people (so-called hippies). It became a rallying cry for people to band together and question the flaws in government. The lines also provide an optimistic assurance to those who stand up to change the wrongs in society. Th opening line

Come gather 'round people

is a call typical of the folk tradition when you want to spread a message. Existing systems need to change to correct injustices like poverty. Change is happening and they, the people, must be the agents to bring it about by bringing pressure on the government. In this song, Thommo does the lead singing. Click the link below to play the song:

Thommo & Geetha – The Times They Are A Changing

A great round of applause followed.

Joe, speaking up for Dylan and said:

“This man won the Nobel for Literature but odes and elegies like this have in those times contributed more to bringing about peace than several Americans who actually got the Nobel Peace Prize and I can name two who didn’t deserve it – Kissinger, who was a real war-criminal; and Obama who did nothing for peace, instead prolonged wars. But Bob Dylan does deserve it. These songs are such well-crafted calls to people to realise that they are being obsoleted by facts that are changing the ground underneath their feet. They better come aboard and realise:

the wheel's still in spin

And there's no tellin' who

That it's namin'

For the loser now

Will be later to win

For the times they are a-changin'

Dylan’s telling the Senators and Congressmen: if you want to win, come aboard. The direction in which the winds are blowing and the times are changing point to great lyrics. They demonstrate how you can be subtle, you can go to the core of your message, without being violent, without being cynical, without being virulent or shrill. I would say these lyrics embody true eloquence and when it’s wedded to music as he has done – imagine what a groundswell of change this one one man gave rise to! Of course, there was a coterie of musicians who propelled folk-singing at the time from Pete Seeger and Joan Baez, to Woody and Arlo Guthrie. Bob Dylan was in the forefront. Great credit to him. I think we have to tip our hats to honour him. ”

Joan Baez and Bob Dylan were in a close relationship for several years, Thommo said. Yes, exactly. Shoba has sung a song where Joan Baez speaks of Dylan ditching her although she can claim to have launched him. It’s called Diamonds and Rust. Geeta mentioned that an aunt of hers in Paris had met Joan Baez in her professional work. Joan’s father, Alberto Baez, a physicist, worked for UNESCO and was stationed there for a while. Geeta thought Joan’s parents were not appreciative of their daughter taking to the life of a folk-singer; it was true they had reservations because they worried about the drug scene. But they were there at the Newport Jazz Festival in Newport, Rhode Island, when she sang in July, 1967.

Joan Baez poses for a portrait with Albert Baez (l), her father, and Joan Bridge Baez (r), her mother, at the Newport Folk Festival in July, 1967 in Newport, Rhode Island

Arundhaty and Shoba said she is still very elegant and stylish. Joan Baez remains undiminished by time:

Joan Baez, American folk singer, songwriter, musician and a prominent activist in the fields of human rights, peace and environmental justice

Gopa

She undertook to recite a poem by Rabindranath Tagore, but gave no introduction saying that the readers must have seen our supreme leader mimicking Tagore’s flowing beard in an attempt to appear wise. He tried to impress the electorate in Bengal with a few Bengali phrases but it was all sham and people were not deceived.

The Bengali title of the poem is Mukto Pathey, meaning on the path to freedom. The translation is by William Radice. Radice is an English poet and translator of many books from Bengali. His is the first of the modern translations that try to render what is in the poems of Rabindranath without glossing over the difficulties. His book Rabindranath Tagore; Selected Poems covers 48 poems, selecting 16 each from the early, middle and late period of the poet's life. At the back he provides extensive notes to each poem: the original title in Bengali, the volume of Rabindranath's verse from which it is taken, the political background of the times, the poet's state of health, the place it was written, and what events occasioned the poem, and where it was first published. It is an excellent first volume for entry into Tagore’s verse. The Introduction to Radice’s volume, free to read online, is excellent reading at KRG for those who want a substantial idea of what Tagore accomplished in Bengali poetry. The poem Gopa read, Freedom-bound, is from the late period (1937–1941) of the poet.

Gopa acknowledged that she got the poem from Radice’s book presented to her by KumKum. The poem was published in 1940 in a collection called Shanai, that is shehnai, the musical instrument. It was a time when Tagore went to Maitreyi Devi’s house and he stayed there and wrote a lot of poems that appear in this collection, while also composing songs. The path to liberation in this case is epitomised by a rustic woman, unfettered by conventional life. Love plays an important role because she loves what she does, she has no concept of shame. She is happy in her own being and that is the sort of liberation Tagore yearns for. It is a path to liberation.

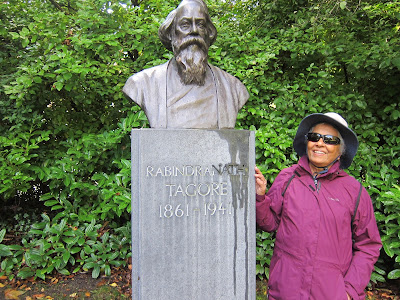

KumKum next to the bust of Tagore in Saint Stephens Green, Dublin

The image is of an outcaste woman who brings her wares to market, poorly clad, but free and joyful in her state

You are ashamed to be ashamed

By lack of ornament –

No amount of dust can spoil

Your plain habiliment.

…

You cross the stream with dripping sari

Tucked up to your knees –

The poet-observer has a keen eye:

I find you when and where I choose,

Whenever it pleases me –

No fuss or preparation: tell me,

Who will know but we?

The first four lines are to warn off the poet’s genteel bhadralok contemporaries not to censure him for having a glad eye for this young out-of-caste woman:

Frown and bolt the door and glare

With disapproving eyes,

Behold my outcaste love, the scourge

Of all proprieties.

Gopa liked the poem for setting out the attractiveness of a poor rustic girl who went about her activities naturally, in spite of her being poor and beyond the pale of well-off society. Talitha said it’s all very nicely observed for the poet, but what’s in it for her? Gopa answered with the lines:

You brought from somewhere lotus honey

In your pot of clay.

You came because you heard I like

Love simple, unadorned –

She comes because he appreciates what she brings. Though unsaid, she is the lover, according to KumKum. She suggested it may be an allusion to the life of Ramkinkar Baij, the sculptor, who lived and worked in Santiniketan with a beautiful Santhal woman. What in other institutions would have been cause for scandal didn’t matter in Santiniketan. They never got married but had two children. Tagore accepted that norm. Though he himself was married to a Brahmin woman, the idea of an out of caste alliance did not cause any tremor in his mind.

Why is a Santhal outcaste, asked Joe? Because she is a tribal came the pat answer. Arundhaty said Baij has sculpted a powerful image of a Santhal family striding forward with a woman thrusting apace with her man:

Santhal Family by Ramkinkar Baij - installed at Santiniketan, made of the lateritic soil of the place mixed with cement

Arundhaty said they have a number of his cultures at their museum, the Kerala Museum, of the Madhavan Nayar Foundation. Joe said Baij’s sculptures on the grounds of Santiniketan are not well-cared for. Concrete is not a material that stands up well to weathering in the open air; it is friable.

Pamela

There is an interesting essay by Amitav Ghosh on Agha Shahid Ali, a Kashmiri-American poet born in Delhi in 1949. Pamela said she would excerpt a few passages from it. Shahid died of a brain tumour in 2001. His father’s family were Shias from Srinagar. His father was in education, teaching in Jamia Millia Islamia in Delhi, where he was Principal of the Teachers College. It was from here Pamela did her B.Ed. In 1961 he did his PhD in Indiana and his family moved to the US for the next 3 years in Pennsyvlania.

In 1997 Shahid wrote a collection, A Country Without a Post-office. Amitav Ghosh (AG) says he had a lot of telephonic conversations with Shahid in the 1990s and the friendship grew. Shahid had a sorcerer’s ability to transmute the mundane into the magical, says AG. He enjoyed rogan josh, Begum Akhtar and Kishore Kumar.

AG writes:

Over a period of several years Shahid took it on himself to solicit ghazals from a number of poets writing in English. The resulting collection Ravishing DisUnities: Real Ghazals in English was published in 2000. In establishing a benchmark for the form it has already begun to exert a powerful influence: the formalisation of the ghazal may well prove to be Shahid’s most important scholarly contribution to the canon of English poetry.

Agha Shahid Ali, Kashmiri-American poet

He was friendly with James Merrill, whose poems Pamela read before. Under his influence Shahid began to experiment with strict metrical patterns and verse forms such as the canzone and the sestina. Shahid had wanted AG to write about him after his death. Shahid loved parties, loved people around him, and even in hospital he was gay and made people happy. AG writes is his remembrance essay:

When a hospital orderly came with a wheelchair Shahid gave him a beaming smile and asked where he was from. Ecuador, the man said and Shahid clapped his hands gleefully together. “Spanish!” he cried, at the top of his voice. “I always wanted to learn Spanish. Just to read Lorca.”

Shahid tells how he came upon ghazals in English:

“I never thought that I would be able to write about Ghazals in English till I came across a Ghazal written by an American poet named John Hollander. I was very excited and said, ‘Oh! my goodness, why haven’t I thought of this because here’s the tradition I grew up with.’

The poem Tonight is in the ghazal pattern. Since we are talking of ghazals, which have a strict form and Shahid was a stickler, it is well to recapitulate the essentials from an earlier exposition at KRG when Joe recited from Ghalib in 2013:

A ghazal (meaning, a conversation with the beloved) is a traditional form of poetry in Arabic, Persian and Urdu with a few simple rules. It is written in 5 to 12 groups of couplets, called shers. Each sher stands by itself. The first sher is the Matla, and sets out the pattern to be followed in two respects, the Radif and the Qaaffiyaa. The Radif is the ending word (or words) of the second line of the Matla, and it must be repeated as the ending words of every second line of succeeding shers. The word that precedes the Radif is called the Qaafiyaa and it must be rhymed with words in the corresponding position in all the shers of the ghazal. One more rule is that the last sher, the Maqta, should reference in an imaginative way the author by his Takhallus, or pen-name. That’s all there is to it.

In this ghazal in English, there are 13 shers. The Matla is the first sher:

Where are you now? Who lies beneath your spell tonight?

Whom else from rapture’s road will you expel tonight?

From the Matla you observe the Radif is the word ‘tonight,’ and the Qaaffiyaa is the word ‘expel’ standing just before it. In every succeeding sher therefore ‘tonight’ has to stand at the end. And the Radif ‘expel’ is made to rhyme with the penultimate words of each of the 12 succeeding shers:

tell, cell, fell, infidel, spell, Hell, knell, infidel, Jezebel, gazelle, farewell, Ishmael.

And in the last sher stands the poet’s Takhallus, Shahid.

The lead-in line

Pale hands I loved beside the Shalimar

as well as

Where are you now? Who lies beneath your spell tonight?

are both taken from the opening of a poem called Kashmiri Song, written by Laurence Hope, in reality a woman called Adela Florence Nicolson (née Cory) (1865-1904) who wrote under that pseudonym. Here is a picture of the Shalimar Garden in Srinagar:

Shalimar Bagh, a Mughal garden in Srinagar, linked to the Dal Lake, on the outskirts of Srinagar. It was built by Mughal Emperor Jahangir for his wife Nur Jahan, in 1619

Clearly Shahid is apostrophising Kashmir, longing for his homeland which has put a spell on his heart. For a fuller exposition of the ghazal and its allusions consult Tonight — Ghazal by Agha Shahid Ali. It’s striking to hear Shahid say:

Jezebel … has always been described as this bad woman, a harlot. But I now realise that she was quite a brave woman, there is this Elijah who’s screaming at her like a raving fundamentalist. When they come to kill her, she stands at her window, she makes an incredibly heroic picture.

Joe

John Suckling (1609–1642) was among the gentlemanly or courtier poets. Richard Lovelace was another such who wrote that sweet letter to Lucasta on going to war:

I could not love thee (Dear) so much,

Lov’d I not Honour more.

Richard Lovelace is also remembered for his poem to Amarantha:

Amarantha sweet and fair

Ah braid no more that shining hair!

As my curious hand or eye

Hovering round thee let it fly.

Let it fly as unconfin’d

As its calm ravisher, the wind,

Who hath left his darling th’East,

To wanton o’er that spicy nest.

Such were the verses these gentleman poets wrote, as if they were frisking on a restless mare, or riding a wind. Suckling came from a prominent Norwich family. His father was an MP and represented the government in various official positions and was knighted by James I in 1616. John Suckling graduated from Trinity College in 17623, having been privately tutored. He joined an expedition to the Netherlands in the Thirty Years War and also studied in the University of Leyden. He was knighted as Sir John Suckling in 1630 and rejoined diplomatic duties with the ambassador to Sweden.

Sir John Suckling by Anton Van Dyck

He led a life sowing wild oats in gambling dens and incurred debts that wasted his fortune. He courted women to gain a fortune and gained a reputation as a gallant and gamester. He was also involved in some romances and wrote a play, Aglaura. He wrote polemical tracts on religion. Later he was active in the army, and offered advice to the king. His complicity in a plot made him flee to France where he met his death in 1641, it is not known exactly how.

His works are collected as The Last Remains of Sr John Suckling (1659), and The Works of Sir John Suckling (1676). Suckling himself did not play a role, and hence there are doubts about the text. Ben Jonson was the one who did the service.

Suckling’s poems include songs in honour of brides and grooms, poems of praise, poems on love themes, satire, songs and sonnets. He employs iambic tetrameter and iambic pentameter couplets, using stanzaic forms and quatrains. There is strain of carefree expression and humour that yields delight even four centuries on. Joe said, Let me make you party to enjoying a couple of his short ones that I shall recite now.

The first one is called Song: Out upon it, I have lov’d,

Out upon it, I have lov’d

Three whole days together;

And am like to love three more,

If it prove fair weather.

The second Joe recited is Why so pale and wan fond lover? It has lines like these:

Why so pale and wan fond lover?

Prithee why so pale?

Will, when looking well can’t move her,

Looking ill prevail?

Prithee why so pale?

KumKum

KumKum chose a poem by Mark Strand after picking up a book of his poems from her daughter Rachel’s library. She has not come across this poet before. She was tickled that Mark Strand graduated from a liberal arts college, Antioch, in Ohio where Joe taught too.

Bio of Mark Strand

Mark Strand was born in 1934 on Prince Edward Island, Canada. Because his father had a transferable job the young poet lived in various cities across the United States, Colombia, Mexico and Peru, and grew up in many cultures, learning many languages.

Mark Strand in New York in 2000, the year after he won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for his collection 'Blizzard of One’

Eventually Mark Strand became a citizen of the United States. He got his BA from Antioch College in 1957 and a BFA from Yale University in 1959. Strand wanted to be an artist, but later realised he wasn't good enough. He chose literature instead.

Following his graduation, he went to Italy on a Fulbright Scholarship and there he studied 19th Century Italian Poetry. Strand got his MFA from the Iowa Writers' Workshop in 1962. He taught at Yale University, Princeton University and Harvard University. He also spent a year in Brazil teaching. Mark Strand was a successful teacher; all his life he was engaged in teaching at many prestigious universities in the US.

His first book of poems, Sleeping with One Eye Open was published in 1964. This was followed by many more. He wrote essays, short stories too.

Mark Strand was recognised with numerous awards, Honours, including the Pulitzer Prize for his poetry collection, Blizzard of One. He was named the US Poet Laureate in 1990.

Mark Strand died at age 80, in 2014 of Cancer.

The poem Old People On the Nursing Home Porch is about senior citizens at an old age home. Some lines resonated with KumKum:

It is too late to travel

Or even find a reason

To make it seem worthwhile.

KumKum did not read the second poem she chose, The Garden, asking readers to tackle it themselves from the blog post. Here’s another short one by Mark Strand, Keeping Things Whole

In a field

I am the absence

of field.

This is

always the case.

Wherever I am

I am what is missing.

When I walk

I part the air

and always

the air moves in

to fill the spaces

where my body’s been.

We all have reasons

for moving.

I move

to keep things whole.

He said he was once playing cards with another poet when he went to kitchen for a break and wrote this poem in its entirety, and came back to the table, and hasn’t changed a word since. It’s a gift that comes to poets on rare occasions. But to get a taste of a different Mark Strand, lifted to a plane of evocative description by the occurrence of whales feeding on a super-abundance of plankton, you can read his poem Shooting Whales.

Mark Strand makes the perceptive comment that in all communication we understand a good deal more than what is being told to us. Poets have learned over time to keep something of themselves in reserve so that readers can go back and find more in the poem. Probably one can’t do this in fictional narrative.

A poet feels the boredom of repetition unless shee changes, so it’s almost an obligation to try and change as a poet; whether you succeed or not, only the long term history of your writing can tell. You are the prisoner of the words you use, said Mark Strand in an interview. Everyone is recognised by the turns of phrase, the language they prefer, when they choose to speak, what things they choose to speak about. A radical break with any of that would get you in the madhouse.

Mark Strand at a certain point of his career lost confidence, and could not decide what in free verse was poetry, and what was merely dressed-up prose. So he spent a ten-year drought of poetry, writing other things – short stories, children’s books, art criticism, a translation of poems by Carlos Drummond de Andrade from Spanish, and so on. When he returned to poetry he assumed more formal methods.

Shoba

Thomas Hood was born in London. After his father, a bookseller died in 1811, Hood worked in a countinghouse until illness forced him to move to Dundee, Scotland, to recover with relatives. In 1818 he returned to London to work as an engraver. He became an editor, publisher, poet, and humorist.

In 1824 Hood married Jane Reynolds and collaborated on Odes and Addresses with his brother-in-law, J.H. Reynolds. He was known for his light verse and puns, such as these

Ben Battle was a soldier bold,

Well used to war's alarms;

But a cannon-ball took off his legs,

So he laid down his arms.

And further on in this same poem, Faithless Nelly Grey:

The love that loves a red-coat

Should be more uniform!

Here’s another example:

His death, which happened in his berth,

At forty-odd-befell:

They went and told the sexton, and

The sexton toll’d the bell.

Thomas Hood

He wrote sonnets too, and this one called Silence is inspired. It is written with a conventional Italian octave and a Shakespearean sestet, and has a charm all its own:

There is a silence where hath been no sound,

There is a silence where no sound may be,

In the cold grave—under the deep deep sea,

Or in the wide desert where no life is found,

Which hath been mute, and still must sleep profound;

No voice is hush’d—no life treads silently,

But clouds and cloudy shadows wander free,

That never spoke, over the idle ground:

But in green ruins, in the desolate walls

Of antique palaces, where Man hath been,

Though the dun fox, or wild hyena, calls,

And owls, that flit continually between,

Shriek to the echo, and the low winds moan,

There the true Silence is, self-conscious and alone.

This was the poem Shoba chose to read. It distinguishes two kinds of silence; a silence where sound never was nor could ever be, such as the grave:

There is a silence where hath been no sound,

There is a silence where no sound may be,

In the cold grave—under the deep deep sea,

And the other graver silence reigns in places once charged with living beings, but now deserted:

But in green ruins, in the desolate walls

Of antique palaces, where Man hath been,

Though the dun fox, or wild hyena, calls,

And owls, that flit continually between,

Shriek to the echo, and the low winds moan,

There the true Silence is, self-conscious and alone.

Shoba mentioned a priest remarking on how different is the silence in the church during Covid times. Parishioners would throng to the church before and there was a vibrant feeling of prayer. It is cold and silent now.

Hood also depicted the working conditions of the poor in poems such as Song of the Shirt, about a seamstress. His publications include Whims and Oddities (1826 and 1827), National Tales (1827), a collection of stories, and The Plea of the Midsummer Fairies (1827). In the 1830s he traveled to continental Europe and lived with his family in Belgium, which provided inspiration for Up the Rhine (1840). Suffering from ill health and troubled finances, he received a grant from the Royal Literary Fund in 1841.

Hood was associated with a number of magazines throughout his life: the London Magazine and New Monthly Magazine as an editor, and the Athenaeum as a contributor. He also published a magazine called Laughter from Year to Year and released the Comic Annual series. As a member of the London literary scene, he was familiar with literary contemporaries such as Coleridge, Thomas De Quincy, William Hazlitt, Charles Lamb, and William Wordsworth.

An elaborate account of Hood’s life and works can be found in a 1947 Master’s thesis Thomas Hood : poet, social thinker, comedian by Ernest W. Mooney Jr at the University of Richmond, Virginia.

Shoba said Thomas Hood has been dismissed as a lesser poet of the Romantic era. He was known in his lifetime as a comic writer. Today he is known for his more serious work, like Song of the Shirt, which talks of worker exploitation. It was first published in 1843 and the reprinted many times and translated into European languages. Charles Dickens commended it and they had a long friendship.

+++—+++—+++—+++—+++—+++

Having completed the poetry readings, KumKum turned the conversation to the Covid situation in Kerala and asked if it’s improving. Yes, but the new cases remain the same at about 12,000 in EKM district and in Kochi it is 1,500 daily; people are talking of a 3rd wave. The test positivity rate in Devika’s area is 25%, which is high. No vaccination yet for below 45 years of age. Companies are organising vaccination, 400 a day said Thommo. Federal Bank has given all its 10,000 employees the first dose. The Chamber of Commerce is charging Rs 850 for members and Rs 950 for non-members. One can’t believe a few of us got it for Rs 250 each in Mar/Apr from Lakeshore Hospital. Because Priya is not present you can say what you want today about the Supreme Leader whose beard has grown. Grey hair is an advantage in Covid times and it is a boon in airports. But people keep repeating things to the grey-haired folk assuming they are hard of hearing.

Geetha told a joke about an older man who had serious hearing problems for many years. He went to the doctor and the doctor was able to have him fitted for a set of hearing aids that restored the man’s hearing nearly 100%.

The old man went back in a month to the doctor and the doctor said, “Your hearing is perfect. Your family must be really pleased that you can hear again.”

The man replied, “Oh, I haven’t told my family yet. I just sit around and listen to their conversations. I’ve changed my will three times!”

The Poems

Arundhaty

Gomata by Rukmini Bhaya Nair

o cow against the yellow calendula

you do not need another poem

a poem is the last thing on your mind

if I can call that rocky space between the almost paisley

tall tender patterns, the tendu leaves of your ears, a mind

but if it is a mind, and this is a huge, a cosmic, if

it is a buddha mind, carrier of sorrow, unmoved by fear

any one can see that pain, it moves in your bony rump

it shows in the large, dark jewels of your eyes

full of unshed longing

cow, you carry your gender

like a calf, within

so why would you need a poem, cow?

you are the soul of any lyric

you are a poem

yourself, swayambhu

like poetry, you remake yourself

broken and bloodied, and then

milk-fresh

in every calving

a lethal dose of pain and fearlessness

that's poetry

and it was with you in the Geeta

and when you ambled with Yagnavalkya

all through the Brihadaranyaka, making legends

and it is with you now

just watch you walk

in the death's-head traffic

honks and roars and blazes on all ten thousand sides

teetering on your small black patent high-heeled pumps

old-fashioned, dainty, calm as a grandmother among frisky kids

great matriarch in the huddled mists of winter

skittish young thing in summer, wiggling

your frilly dewlap, always the complete

woman, following the herd

being driven

by a man

Gopala

you remember him, child and god

oppressor, exquisite in blue

o cow with the black mouth and champaka body

what centuries speak in your silence, what old flute

blows

his poems still lilt through the boulders of your mind

agonize in its leafy groves, whispering

nothing has changed

though you march with the herd, you are alone

though you are sacred, you are not beloved

thrusting your nose into city garbage

unembarrassed, a fly-blown beggar

driven from the dusty villages

how do you stand it, cow?

you have lived too long with fear to feel afraid

survived Gopala and his antic idylls

nothing disturbs you, nothing

destroys

your peace

your hulking grace

your buddha somnolence

a bulwark against action

but I ask you why, impassive cow?

is this reward enough

is this what it means to be a poem

is this why you grieve, revengeful queen

why you breed and why you just will not die?

o cow in the golden godhuli alo

among the hay-ricks, among

your knobbly calves

jingling home

contented

those horns you wear

what for, cow?

ornaments?

moons on your forehead?

just one other poetic embellishment?

certainly I cannot imagine you using them in self defence

but would you not use them in a war, a holy war

would you not use those horns in battle

that rocky head, those swishy

appendages and sinewy feet?

o cow against the yellow calendula

so immobile, so still, so bloody

beautiful, you could win

anything you wished

everything

you may insist you are a mother, cow

and that you would prefer gentler tactics, but it has

come to this, a fight, a mettlesome tossing of heads

a charge

and now what?

it is not only bulls that charge

that is a myth, an absolute myth

it is the story Gopala got away with

those killing horns, cow, belong to you

and poetry

that is yours too

because you are a poem, and because

you have been a poem, and bred poems, for so long

a poem is always a charge

Gopala’s dharmakshetra, flashing

battleground, place of terrible victories

if you are charged with poetry, cow

if you flaunt on your head

its perfect crescent

if you are

in charge

there is no going back, cow

o cow against the yellow calendula

(Note: This poem from The Ayodhya Cantos (1999) )

Devika

Minority by Imtiaz Dharker

I was born a foreigner.

I carried on from there

to become a foreigner everywhere

I went, even in the place

planted with my relatives,

six-foot tubers sprouting roots,

their fingers and faces pushing up

new shoots of maize and sugar cane.

All kinds of places and groups

of people who have an admirable

history would, almost certainly,

distance themselves from me.

I don’t fit,

like a clumsily translated poem;

like food cooked in milk of coconut

where you expected ghee or cream,

the unexpected aftertaste

of cardamom or neem.

There’s always a point that where

the language flips

into an unfamiliar taste;

where words tumble over

a cunning tripwire on the tongue;

were the frame slips,

the reception of an image

not quite tuned, ghost-outlined,

that signals, in their midst,

an alien.

And so I scratch, scratch

through the night, at this

growing scab on black and white.

Everyone has the right

to infiltrate a piece of paper.

A page doesn’t fight back.

And, who knows, these lines

may scratch their way

into your head –

through all the chatter of community,

family, clattering spoons,

children being fed –

immigrate into your bed,

squat in your home,

and in a corner, eat your bread,

until, one day, you meet

the stranger sliding down your street,

realise you know the face

simplified to bone,

look into its outcast eyes

and recognise it as your own.

Geeta

On Friendship Kahlil Gibran

And a youth said, Speak to us of Friendship.

And he answered, saying:

Your friend is your needs answered.

He is your field which you sow with love and reap with thanksgiving.

And he is your board and your fireside.

For you come to him with your hunger, and you seek him for peace.

When your friend speaks his mind you fear not the “nay” in your own mind, nor do you withhold the “ay.”

And when he is silent your heart ceases not to listen to his heart;

For without words, in friendship, all thoughts, all desires, all expectations are born and shared, with joy that is unacclaimed.

When you part from your friend, you grieve not;

For that which you love most in him may be clearer in his absence, as the mountain to the climber is clearer from the plain.

And let there be no purpose in friendship save the deepening of the spirit.

For love that seeks aught but the disclosure of its own mystery is not love but a net cast forth: and only the unprofitable is caught.

And let your best be for your friend.

If he must know the ebb of your tide, let him know its flood also.

For what is your friend that you should seek him with hours to kill?

Seek him always with hours to live.

For it is his to fill your need but not your emptiness.

And in the sweetness of friendship let there be laughter, and sharing of pleasures.

For in the dew of little things the heart finds its morning and is refreshed.

From The Prophet (Knopf, 1923). This poem is in the public domain.

Geetha-Thommo – two song lyrics by Bob Dylan

Blowing In The Wind

How many roads must a man walk down

Before you call him a man?

How many seas must a white dove sail

Before she sleeps in the sand?

Yes, and how many times must the cannonballs fly

Before they're forever banned?

The answer, my friend, is blowin' in the wind

The answer is blowin' in the wind

Yes, and how many years must a mountain exist

Before it is washed to the sea?

And how many years can some people exist

Before they're allowed to be free?

Yes, and how many times can a man turn his head

And pretend that he just doesn't see?

The answer, my friend, is blowin' in the wind

The answer is blowin' in the wind

Yes, and how many times must a man look up

Before he can see the sky?

And how many ears must one man have

Before he can hear people cry?

Yes, and how many deaths will it take 'til he knows

That too many people have died?

The answer, my friend, is blowin' in the wind

The answer is blowin' in the wind

The Times They Are A Changing

Come gather 'round people

Wherever you roam

And admit that the waters

Around you have grown

And accept it that soon

You'll be drenched to the bone

If your time to you is worth savin'

And you better start swimmin'

Or you'll sink like a stone

For the times they are a-changin'

Come writers and critics

Who prophesize with your pen

And keep your eyes wide

The chance won't come again

And don't speak too soon

For the wheel's still in spin

And there's no tellin' who

That it's namin'

For the loser now

Will be later to win

For the times they are a-changin'

Come senators, congressmen

Please heed the call

Don't stand in the doorway

Don't block up the hall

For he that gets hurt

Will be he who has stalled

The battle outside and it’s ragin'

It’ill soon shake your windows

And rattle your walls

For the times they are a-changin'

Come mothers and fathers

Throughout the land

And don't criticize

What you can't understand

Your sons and your daughters

Are beyond your command

Your old road is rapidly agin'

Please get out of the new one

If you can't lend your hand

For the times they are a-changin'

The line it is drawn

The curse it is cast

The slow one now

Will later be fast

As the present now

Will later be past

The order is rapidly fadin'

And the first one now

Will later be last

For the times they are a-changin'

(Music and lyrics Bob Dylan)

Gopa

Freedom-bound by Rabindranath Tagore

Frown and bolt the door and glare

With disapproving eyes,

Behold my outcaste love, the scourge

Of all proprieties.

To sit where orthodoxy rules

Is not her wish at all –

Maybe I shall seat her on

A grubby patchwork shawl.

The upright villagers, who like

To buy and sell all day,

Do not notice one whose dress

Is drab and dusty-grey.

So keen on outward show, the form

Beneath can pass them by –

Come, my darling, let there be

None but you and I.

When suddenly you left your house

To love along the way,

You brought from somewhere lotus honey

In your pot of clay.

You came because you heard I like

Love simple, unadorned –

An earthen jar is not a thing

My hands have ever scorned.

No bells upon your ankles, so

No purpose in a dance –

Your blood has all the rhythms

That are needed to entrance.

You are ashamed to be ashamed

By lack of ornament –

No amount of dust can spoil

Your plain habiliment.

Herd-boys crowd around you, street-dogs

Follow by your side –

Gipsy-like upon your pony

Easily you ride.

You cross the stream with dripping sari

Tucked up to your knees –

My duty to the straight and narrow

Flies at sights like these.

You take your basket to the fields

For herbs on market-day –

You fill your hem with peas for donkeys

Loose beside the way.

Rainy days do not deter you –

Mud caked to your toes

And kacu-leaf upon your head,

On your journey goes.

I find you when and where I choose,

Whenever it pleases me –

No fuss or preparation: tell me,

Who will know but we?

Throwing caution to the winds,

Spurned by all around,

Come, my outcaste love, O let us

Travel, freedom-bound.

(Translated by William Radice)

Joe – two poems by John Suckling

Song: Out upon it, I have lov’d

Out upon it, I have lov’d

Three whole days together;

And am like to love three more,

If it prove fair weather.

Time shall moult away his wings,

Ere he shall discover

In the whole wide world again

Such a constant lover.

But the spite on’t is, no praise

Is due at all to me;

Love with me had made no stays,

Had it any been but she.

Had it any been but she,

And that very face,

There had been at least ere this

A dozen dozens in her place.

Song: Why so pale and wan fond lover?

Why so pale and wan fond lover?

Prithee why so pale?

Will, when looking well can’t move her,

Looking ill prevail?

Prithee why so pale?

Why so dull and mute young sinner?

Prithee why so mute?

Will, when speaking well can’t win her,

Saying nothing do’t?

Prithee why so mute?

Quit, quit for shame, this will not move,

This cannot take her;

If of herself she will not love,

Nothing can make her;

The devil take her.

KumKum – two poems by Mark Strand

Old People On the Nursing Home Porch

Able at last to stop

And recall the days it took

To get them here, they sit

On the porch in rockers

Letting the faded light

Of afternoon carry them off

I see them moving back

And forth over the dullness

Of the past, covering ground

They did not know was there,

And ending up with nothing

Save what might have been.

And so they sit, gazing

Out between the trees

Until in all that vacant

Wash of sky, the wasted

Vision of each one

Comes down to earth again.

It is too late to travel

Or even find a reason

To make it seem worthwhile.

Already now, the evening

Reaches out to take

The aging world away.

And soon the dark will come,

And these tired elders feel

The need to go indoors

Where each will lie alone

In the deep and sheepless

Pastures of a long sleep.

The Garden

for Robert Penn Warren

, It shines in the garden,

in the white foliage of the chestnut tree,

in the brim of my father's hat

As he walks on the gravel.

In the garden suspended in time

my mother sits in a redwood chair;

light fills the sky,

the folds of her dress,

the roses tangled beside her.

And when my father bends

to whisper in her ear,

when they rise to leave

and swallows dart

and the moon and stars

have drifted off together, it shines.

Even as you lean over this page,

late and alone, it shines; even now

in the moment before it disappears.

Pamela

Tonight by Agha Shaid Ali

Pale hands I loved beside the Shalimar

—Laurence Hope

Where are you now? Who lies beneath your spell tonight?

Whom else from rapture’s road will you expel tonight?

Those “Fabrics of Cashmere—” “to make Me beautiful—”

“Trinket”—to gem—“Me to adorn—How tell”—tonight?

I beg for haven: Prisons, let open your gates—

A refugee from Belief seeks a cell tonight.

God’s vintage loneliness has turned to vinegar—

All the archangels—their wings frozen—fell tonight.

Lord, cried out the idols, Don’t let us be broken;

Only we can convert the infidel tonight.

Mughal ceilings, let your mirrored convexities

multiply me at once under your spell tonight.

He’s freed some fire from ice in pity for Heaven.

He’s left open—for God—the doors of Hell tonight.

In the heart’s veined temple, all statues have been smashed.

No priest in saffron’s left to toll its knell tonight.

God, limit these punishments, there’s still Judgment Day—

I’m a mere sinner, I’m no infidel tonight.

Executioners near the woman at the window.

Damn you, Elijah, I’ll bless Jezebel tonight.

The hunt is over, and I hear the Call to Prayer

fade into that of the wounded gazelle tonight.

My rivals for your love—you’ve invited them all?

This is mere insult, this is no farewell tonight.

And I, Shahid, only am escaped to tell thee—

God sobs in my arms. Call me Ishmael tonight.

Shoba

Silence by Thomas Hood

There is a silence where hath been no sound,

There is a silence where no sound may be,

In the cold grave—under the deep deep sea,

Or in the wide desert where no life is found,

Which hath been mute, and still must sleep profound;

No voice is hush’d—no life treads silently,

But clouds and cloudy shadows wander free,

That never spoke, over the idle ground:

But in green ruins, in the desolate walls

Of antique palaces, where Man hath been,

Though the dun fox, or wild hyena, calls,

And owls, that flit continually between,

Shriek to the echo, and the low winds moan,

There the true Silence is, self-conscious and alone.

Talitha

The River-Merchant’s Wife: A Letter by Ezra Pound

(After Li Po)

While my hair was still cut straight across my forehead

I played about the front gate, pulling flowers.

You came by on bamboo stilts, playing horse,

You walked about my seat, playing with blue plums.

And we went on living in the village of Chōkan:

Two small people, without dislike or suspicion.

At fourteen I married My Lord you.

I never laughed, being bashful.

Lowering my head, I looked at the wall.

Called to, a thousand times, I never looked back.

At fifteen I stopped scowling,

I desired my dust to be mingled with yours

Forever and forever, and forever.

Why should I climb the look out?

At sixteen you departed

You went into far Ku-tō-en, by the river of swirling eddies,

And you have been gone five months.

The monkeys make sorrowful noise overhead.

You dragged your feet when you went out.

By the gate now, the moss is grown, the different mosses,

Too deep to clear them away!

The leaves fall early this autumn, in wind.

The paired butterflies are already yellow with August

Over the grass in the West garden;

They hurt me.

I grow older.

If you are coming down through the narrows of the river Kiang,

Please let me know beforehand,

And I will come out to meet you

As far as Chō-fū-Sa.

Thank you, thank you, thank you for a wonderful morning booster.... like a good cup of coffee, is your blog dear Joe. Thoroughly enjoyed going through it!

ReplyDeleteGod bless

Thank you, thank you, thank you for a wonderful morning booster.... like a good cup of coffee, is your blog dear Joe. Thoroughly enjoyed going through it!

ReplyDeleteGod bless

Geetha

God bless