Four of the major Romantic Poets were on exhibit at this session: Wordsworth, Shelley, Keats, and Byron. Women poets of the romantic era were included – Mary Robinson and Felicia Heymans, and one who belongs to the Victorian age of poetry, Elizabeth Barrett Browning. William Cullen Bryant was the only poet from outside Britain.

The poems were all new and captivating. Keats marvelled at Byron:

Byron! how sweetly sad thy melody!

Attuning still the soul to tenderness,

Byron lamented the separation from his wife Milbanke, and especially from their daughter Ada. She was to become famous in her own right as the world’s first programmer – of an autonomous computing machine called the Difference Engine invented by Charles Babbage. Byron writes to Milbanke:

When her little hands shall press thee,

When her lip to thine is pressed,

Think of him whose prayer shall bless thee,

Think of him thy love had blessed!

Shelley likewise is writing to his first wife Harriet from whom he soon separated. But before the break he wrote several poems filled with romantic sentiments in his Esdaile Notebook of 56 poems which remained unpublished until 1964. This one to Harriet tugs at the heartstrings:

For a heart as pure and a mind as free

As ever gave lover, to thee I give,

And all that I ask in return from thee

Is to love like me and with me to live.

Wordsworth came alive with his sonnet, The World Is Too Much With Us, which emphasises humankind’s lack of attention to things that matter, instead being preoccupied with

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers;—

This provoked thought among the readers on similar but not identical activities in which moderns fritter away their time, ignoring Nature – ‘we are out of tune,’ Wordsworth says. Joe was engaged to write a modernised version of Wordsworth’s sonnet referring to our Amazon buying, and our fixation on mobile phone screens. Which he has done and included in the blog below.

Setting aside the childhood poem Casabianca which everyone must have learned in middle school, Saras chose Felicia Hemans’ poem The Spanish Chapel. A mother who has lost a child is commiserating her in a chapel’s cemetery:

The soft lip's breath was fled,

And the bright ringlets hung so still—

The lovely child was dead!

It is a tender moment when the mother is descried nearby, yielding

An angel thus to Heaven!"

From Hemans we veered to the marvellous poet, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, who had the good fortune, though, disabled, to find a kindred spirit in another great poet, Robert Browning. The sonnets she wrote for him must rank as love poetry that will live forever. Fortunate are those young lovers even today who have read Sonnets from the Portuguese, in each other’s company.

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and ideal grace.

Full Account and Record of the Session on Aug 19, 2024

Arundhaty

Arundhaty chose a poem by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, her most famous sonnet How Do I Love Thee? (Sonnet 43).

Elizabeth Barrett Browning is not strictly a Romantic poet but with her husband Robert Browning, Lord Tennyson, Matthew Arnold, Gerard Manley Hopkins, and Oscar Wilde was among the famous Victorian poets. She has been read before at KRG. Arundhaty chose this because it is a poem of romantic love told with exuberance, and was therefore fitting for a session celebrating the Romantics poet.. It’s a beautiful poem and Arundhaty thought to go the whole hog and find a poem which not only qualifies in that genre, but also is truly romantic, descriptive of the elements of love, and a very emotional poem to boot.

The poem portrays love as an all-encompassing force that transcends time and space. The speaker's love for her beloved is not just physical but also emotional, spiritual and intellectual. The poem also highlights the transformative power of love as it can bring joy and meaning to life.

Her biography is given below. Briefly, she was born in on March 6, 1806 in Durham, England and began writing when the Romantic movement was coming to a close.

She was oldest among 12 children; her father was a bit of a tyrant and she had a difficult life. She also suffered a lot of sickness but through it all she wrote poetry and her first poem was published when she was 12 years old.

Elizabeth was six year older than her future husband Robert Browning. They exchanged 574 letters over the 20 months after she fell in love with him. Her father did not allow the marriage; so they eloped and got married and her father never spoke to her again.

This sonnet, How Do I Love Thee?, is number 43 from the collection of 44 love sonnets written for Robert Browning between 1845 and 1846, and first published in 1850.

The 14 lines of the sonnet are in iambic pentameter with a rhyme scheme of ABBA ABBA CDCED EEE.

Elizabeth Browning was also an activist which was very unusual in her time. She wrote poems against slavery and some of her poems also addressed problems like child labour . At that time she was an ardent abolitionist of slavery and her poem Runaway Slave at Pilgrim's Point is a very famous poem which she wrote in 1840.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning died in Florence on June 29, 1861.

Her poems had political and social themes and she was very well recognised and admired by various other poets like Emily Dickinson, Virginia Woolf, and Oscar Wilde.

Arundhaty then read the poem.

By listing these different ways of loving her partner, she emphasises the depth and complexity of her feelings and suggests that love can take many different forms. The use of vivid imagery and forceful language such as depth and breadth and height and breadth, smiles, tears –– helps to convey the intensity and passion of the speaker's love.

She also says that if God were to permit, she would love Robert Browning even more after her death than she loved him on this earth, thus implying her love is eternal.

This line, I love thee to the depth and breadth and height is actually from the Bible, describing God's love, said Pamela. Joe inquired its provenance. Later she supplied chapter and verse: Ephesians 4:18:

“And I pray that you being rooted and established in love, may have power together with all the saints, to grasp how wide and long and high and deep is the love of Christ, …”

KumKum acknowledged the origins and said she didn't know that. As a sidebar, it was a copy of Sonnets From The Portuguese that Joe presented to KumKum when they first met in the flesh after a long epistolary acquaintance.

Many poems take the Bible as an inspiration. This poem is a beautiful poem, everyone agreed.

Joe asked if people knew why it is called Sonnets From The Portuguese. Robert Browning used to refer to her as ‘my little Portuguese’, presumably because of her complexion being sallow and her stature short. Later Thomo added the information that Elizabeth was the first in her family in 200 years to be born in England, for the family was partly Creole and had resided in Jamaica as plantation owners.

Links

Joe saw the 1957 movie long ago in Calcutta. It has Jennifer Jones as Elizabeth Barrett, Bill Travers as Robert Browning, and John Gielgud playing the father. But it is not available for streaming anywhere except as a Russian dubbed and overlaid sound which spoils the movie for English speakers:

However, the 1934 Movie in B&W full (1h 50m) with Norma Shearer, Charles Laughton, and Fredric March is available:

Readers can see a 12 min video of the love story of EBB and RB ending with the recitation of sonnet 43:

Elizabeth Barret Browning Bio

Born on March 6, 1806, at Coxhoe Hall, Durham, England, Elizabeth Barrett Browning was an English poet of the Romantic Movement. The oldest of twelve children, Elizabeth was the first in her family born in England in over two hundred years. For centuries, the Barrett family, who were part Creole, had lived in Jamaica, where they owned sugar plantations and relied on the forced labor of enslaved individuals. Elizabeth’s father, Edward Barrett Moulton Barrett, chose to raise his family in England, while his fortune grew in Jamaica. Educated at home, Elizabeth apparently had read passages from John Milton’s Paradise Lost and a number of Shakespearean plays, among other great works, before the age of ten. By her twelfth year, she had written her first “epic” poem, which consisted of four books of rhyming couplets. Two years later, Elizabeth developed a lung ailment that plagued her for the rest of her life. Doctors began treating her with morphine, which she would take until her death. While saddling a pony when she was fifteen, Elizabeth also suffered a spinal injury. Despite her ailments, her education continued to flourish. Throughout her teenage years, Elizabeth taught herself Hebrew so that she could read the Old Testament; her interests later turned to Greek studies. Accompanying her appetite for the classics was a passionate enthusiasm for her Christian faith. She became active in the Bible and Missionary Societies of her church.

In 1826, Elizabeth anonymously published her collection An Essay on Mind and Other Poems. Two years later, her mother passed away. The slow abolition of slavery in England and mismanagement of the plantations depleted the Barretts’ income, and in 1832, Elizabeth’s father sold his rural estate at a public auction. He moved his family to a coastal town and rented cottages for the next three years, before settling permanently in London. While living on the sea coast, Elizabeth published her translation of Prometheus Bound (1833), by the Greek dramatist Aeschylus.

Gaining attention for her work in the 1830s, Elizabeth continued to live in her father’s London house under his tyrannical rule. He began sending Elizabeth’s younger siblings to Jamaica to help with the family’s estates. Elizabeth bitterly opposed slavery and did not want her siblings sent away. During this time, she wrote The Seraphim and Other Poems (1838), expressing Christian sentiments in the form of classical Greek tragedy. Due to her weakening disposition, she was forced to spend a year at the sea of Torquay accompanied by her brother Edward, whom she referred to as “Bro.” He drowned later that year while sailing at Torquay, and Elizabeth returned home emotionally broken, becoming an invalid and a recluse. She spent the next five years in her bedroom at her father’s home. She continued writing, however, and in 1844 produced a collection entitled simply Poems. This volume gained the attention of poet Robert Browning, whose work Elizabeth had praised in one of her poems, and he wrote her a letter.

Elizabeth and Robert, who was six years her junior, exchanged 574 letters over the next twenty months. Immortalized in 1930 in the play The Barretts of Wimpole Street, by Rudolf Besier (1878–1942), their romance was bitterly opposed by her father, who did not want any of his children to marry. In 1846, the couple eloped and settled in Florence, Italy, where Elizabeth’s health improved and she bore a son, Robert Wideman Browning. Her father never spoke to her again. Elizabeth’s Sonnets from the Portuguese, dedicated to her husband and written in secret before her marriage, was published in 1850. Critics generally consider the Sonnets—one of the most widely known collections of love lyrics in English—to be her best work. Admirers have compared her imagery to Shakespeare and her use of the Italian form to Petrarch.

Political and social themes embody Elizabeth’s later work. She expressed her intense sympathy for the struggle for the unification of Italy in Casa Guidi Windows (1848–51) and Poems Before Congress (1860). In 1857 Browning published her verse novel Aurora Leigh, which portrays male domination of a woman. In her poetry she also addressed the oppression of the Italians by the Austrians, the child labour mines and mills of England, and slavery, among other social injustices. Although this decreased her popularity, Elizabeth was heard and recognised around Europe.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning died in Florence on June 29, 1861.

Devika

Devika chose Mary Robinson for the Romantic Poets session, and Shoba did likewise. We've never done Mary Robinson before, though she's written so many poems. ‘Let me have a woman poet,’ thought Devika. The title of the poem is very long, Lines on hearing it declared that no Women were so handsome as the English, which was also something distinctive. But it is far being the longest name of a poem because Lines Written a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey, on Revisiting the Banks of the Wye during a Tour, July 13, 1798, is the even longer title of a Wordsworth poem.

Mary Robinson was an English actress, poet, dramatist, novelist, and a celebrity figure. Something Devika liked was the drama in her life, her love affair with Prince of Wales; she seemed quite a character. Devika proceeded to read the poem and then took questions.

Joe said that from what Devika told of Robinson she did not earn anything from her poetry during her lifetime. Most of it came after her death, said Devika. It's one of the reasons why she died poor.

Joe noted that in the poem she takes off addressing the women of all the different races, from all over the world. That's beautiful. Pamela likes the words she has picked for Indians and Africans, ‘varnished and jetty.’ How adroitly she has avoided the colour question, said Pamela, but look jetty means ‘jet-black,‘ said Joe

Thank you for introducing us to a new poet, KumKum said.

Mary Robinson Bio – 27th November 1757 to 26th December 1800

Mary Robinson known as Perdita (‘the lost one’), portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1782

Mary Robinson was an English actress, poet, dramatist, novelist and celebrity figure. She lived in England in the cities of London and Bristol. She also lived in France and Germany. Mary enjoyed poetry from the age of 7 and started working as a teacher and actress from the age of 14.

Mary Robinson packed a lot of London society life into her relatively short life and was memorable as a “lady about town.” As a poet though her name is much less remembered. Her 18th century efforts to break into the literary scene was a failure and some critics have even suggested that she was usually writing under the influence of the drug laudanum.

Mary Darby Robinson was born to a sea captain and his wife. Her father deserted her mother when Mary was still a young child. Mrs. Darby supported herself and her children by starting a school for young girls. Mary taught at this school at the age of 14. However, on one of his brief returns to the family, the Captain had the school closed (as he was entitled to do by English Law).

Mary at the age of 16 married an Articled Clerk, Thomas Robinson. The couple lived beyond their means and Thomas was imprisoned for debt. Mary and their daughter lived in the prison with him.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge was known to be an inspiration for her but alas her poetic efforts fell a long way short of his. But Coleridge referred to her as “a woman of undoubted genius.”

Despite this her output of poetry was substantial and like many other writers, her work was appreciated more after her death than when she was alive. As a poet she was prolific and innovative, with two collections published posthumously. Her poetry is characterised by an insurgent spirit commonly associated with poets of the Romantic period. Most of her work demonstrates Mary’s interest in marginalised downtrodden figures of society while others reveal a fascination for the fantastic dreamlike states of semi-conscious and magical.

Mary earned the nickname Perdita for her role as Perdita in The Winter’s Tale in 1779. This was when she caught the eye of the Prince of Wales. She was the first public mistress of King George IV, while he was still prince. After her relationship with the Prince of Wales ended, Mary attempted to blackmail The Crown by threatening to make public the letters the prince wrote to her during their affair. She was after the £20,000 the prince had promised her. She was able to obtain only a small annuity, paid sporadically, and lived separately from her philandering husband and went on to have several love affairs on her own.

From the late 1780s, Robinson became distinguished for her poetry and was called ‘the English Sappho.’ She died in poverty at Surrey on 26th December 1800, having survived several years of ill health, and was survived by her daughter, Maria Elizabeth, who was also a published novelist. One of Robinson's dying wishes was to see the rest of her works published. She tasked her daughter, Maria Robinson, with publishing most of these works. She also placed her Memoirs in the care of her daughter, insisting that she publish the work. Maria Robinson published Memoirs just a few months later.

Links to sources:

Geetha

Geetha was reciting from Keats on this occasion, from a poem called An Extempore. John Keats as we all know, was one of the great English Romantic poets. His father died very early and his mother remarried him almost immediately. Throughout his life, he was close to his sister, Fanny, and his two brothers, George and John. After the breakup of their mother's second marriage, the Keats children lived with their old grandmother.

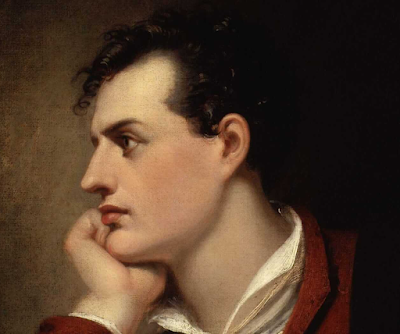

John Keats

This poem is actually very different from Keats’ other poetry. It's quite enjoyable, and very different from his usual poems. This presents a humorous and satirical take on fairy lore and female vanity. It depicts a spoiled princess and her three servants, the dwarf, ape, and the fool, who arrive at an empty fairy court despite being warned of dire consequences for trespassing. The princess enters driven by the desire to display her beauty. The poem ends with the mule, who has been abandoned by his riders, and breaks free, revelling in his newfound liberty.

KumKum said she’d never read this poem. It's a wonderful kid's poem, quite unlike his sonnets and odes. She said she would read this carefully again, and thanked Geetha for finding this uniquely different Keats poem.

KRG readers have had many occasions to write accounts of the life of Keats. One such is here from 2017.

To celebrate the two-hundredth anniversary of Keats’ death in 2021, a foundation created a C.G.I. rendering that looked and spoke like he did. You can hear a 1h 5m presentation about bringing Keats back to life, organised by the Oxford Institute for Digital Archeology:

For help with the way Keats would have pronounced words a linguistic historian Dr Ranjen Sen of the University of Sheffield was called in. He opined that Keats’ accent would have had distinctive features, including emphasising the final ‘t’ in words like ‘fat,’ ‘cat,’ etc. and his Cockney would have been unrecognisable to modern Londoners. It would have bits of northern and west country, said Ranjen Sen. Two new poems by Scarlett Sabet and Simon Armitage (the Poet Laureate) were commissioned, which you can hear recited.

Keats life mask (left) and death mask (right)

The animating of Keats starts at time = 46.00 in the above presentation, from the The Keats - Shelley House in Rome where he died on February 23, 1821. The CGI Rendition of Keats begins at 1:01:24 – he recited Bright Star.

Joe

Joe read the poem To Harriet that Shelley wrote to his first wife, Harriet Westbrook. Her father was a successful owner of a coffee house in London, and sent his two daughters to an excellent girls’ school. Eliza, Harriet’s sister was 30, twice Harriet’s age when she grew intimate with Shelley, and one day in 1811 they ran off to Scotland to be married after Harriet's sixteenth and his nineteenth birthday. The families were surprised. Shelley wrote several poems to her and this is an early expression of his love, composed in 1812 when he was twenty, barely gaining a foothold in the poetic firmament. 85% of the words in the poem have just one syllable.

It begins:

Harriet! thy kiss to my soul is dear;

At evil or pain I would never repine

If to every sigh and to every tear

Were added a look and a kiss of thine.

The poem was labelled ‘beautiful’ by Pamela. Yes, what could be more romantic than that? – she said. She loved the lines:

And all that I ask in return from thee

Is to love like me and with me to live.

Joe said every boy and girl in love has wished that, but most of them have been disappointed. But here Shelley actually eloped with Harriet and they got married.

The poem has a musical lilt. It has 4 octets rhymed ababcdcd. It was composed in 1812 when Shelley was 20. It seems to show a spontaneous feeling for Harriet, quite sincere, and in that respect is more authentic than a more elaborate one he wrote To Harriet (‘It is not blasphemy’). Instead of talking about Shelley, whose life figures several times in the KRG blog, Joe chose to tell of Harriet, the first wife of Shelley, who is the subject and the object of the poem he read. The poem is taken from p. 93 of the Esdaile Notebook published in 1964 – more about it later.

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Harriet, born on August 1, 1795. She was known to be intelligent and charming; she was involved in her husband’s work and followed his projects, both literary and political. But there was some friction, perhaps caused by her elder sister Eliza whom she loved. In 1814 they were remarried in London to afford the protection of English law to her offspring. Two children issued from the marriage, Ianthe (born June 1813) and Charles (born November 1814). By that time the couple had separated; Shelley had met Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, and begun a romance with her, who was to be the future Mrs Shelley, author of Frankenstein and a creative writer. She was ultimately instrumental in publishing the posthumous poems of Shelley, as well as editing the many fragments of incomplete poetry he left behind.

Shelley‘s new found love Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, and his discarded wife Harriet Westbrook, Illustration by Divya Srinivasan

Harriet’s father had settled £200 a year on her; Shelley gave £100 a year at first, and later doubled it. Being financially secure is one thing. But having two young babies and now abandoned, Harriet was not in a good way emotionally. She lived independently in lodgings hired in 1816. In December of that year she walked from her flat to Hyde Park and drowned herself in the Serpentine river that flows through the park. She was only 21. Her babies were brought up by Eliza. You can read a fuller account of her suicide at:

To end Joe mentioned a precious resource called The Esdaile Notebook (EN) which survived in manuscript form, a photographic facsimile of which has been made available by the New York Public Library through its Carl H. Pforzheimer Collection of Shelley and His Circle. See:

The EN was very painstakingly edited, a preface written, annotated and printed as a book in 1964 by Kenneth Neill Cameron:

To Harriet by Shelley – 2 pages of the holograph version

The EN contains about 57 unpublished poems of Shelley; it was compiled by Shelley before he met Mary Godwin, and was presented by him to his first wife Harriet Westbrook. Ianthe, his daughter by Harriet inherited it, and she married the banker Edward Jeffries Esdaile in 1837. The EN Shelley gave to Harriet was passed on through his descendants in the Esdaile family. It was not published until permission was finally given in 1962. It is from among these poems Joe selected the one to recite today.

It's quite curious to think that the 57 poems of Shelley first saw the light of day only in 1962. So when some of us readers say, we've finished Blake, we've finished Wordsworth, we've finished Byron, we've finished Keats, we've finished Shelley, we've finished Coleridge, and so on –– it’s not true at all.

There's lots and lots and lots of poems. Johns Hopkins University is currently publishing the seventh volume of the complete works of Shelley. So please remember there's oodles of stuff that the romantics have written. Some of them, unfortunately, are fragments, because the poets couldn't complete them.

But these are all poets who recorded extensively in notebooks. They carried their notebooks with them, as they travelled.

The written page in a notebook is going to last far, far longer than any email, any computer document, anything in the Cloud, anything in a Google data base or anything electronic.

And the proof is all these things that have lasted us. Of course, there were no books at the time of the Sumerians, but just look at the clay tablets that they've written, left to us from 3,500 BCE – they're still being decoded.

Sumerian Clay Tablet

What you write in a book, or the equivalent of what is a book, handwritten by you as an individual writer, author, recorder, chronicler, accountant, or whatever –– is going to persist.

Kavita

Kavita was going to read from Wordsworth, a poet who has been recited many times before. Therefore we have his biography already gracing the KRG blog. We have done William's Wordsworth many times. But she mentioned a few brief things in his life. Kavita’s very first first session at KRG was to read two poems of William Wordsworth, Daffodils and The Solitary Reaper. That was on May 12th, 2012.

William's Wordsworth was born in Cockermouth, Cumberland on April 7th, 1770. He was the English romantic poet who started it all, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and helped launch the Romantic movement in English literature with their joint publication, Lyrical Ballads, in 1798.

Wordsworth's magnum opus is generally considered The Prelude or, Growth of a Poet's Mind; An Autobiographical Poem of his early years that he revised and expanded a number of times. Wordsworth was Poet Laureate from 1843 until his death on April 23rd, 1850. He was married to Mary Hutchison, whom he praised in his poem She Was a Phantom of Delight as

A perfect Woman, nobly planned,

To warn, to comfort, and command;

Wordsworth had five children. Is that enough, asked Kavita?

William Wordsworth

Meaning had she provided enough of a biographical introduction to Wordsworth. Yes, the readers said in chorus.

For this session Kavita chose the poem, The World Is Too Much With Us. William Wordsworth laments the withering connection between humankind and Nature. Everyone is so busy with their life, tied down by their financial obligations that they have no time to appreciate Nature. This has resulted in destroying a vital part of our humanity. We have lost our ability to connect with Nature and find tranquility therein.

Kavita noted Wordsworth was writing this in 1770. Don’t you think it is applicable with greater force today? Everyone is so busy with their day-to-day lives, that there just isn’t time to enjoy Nature. Further, Kavita noted, we’re destroying Nature around us, through industrialisation, and the extractive exploitation of resources. We have destroyed our natural surroundings, and not left much for our children and grandchildren to enjoy.

Hence, what Wordsworth wrote in 1770, is doubly applicable now.

After Kavita read the poem Joe commented on Wordsworth’s lines

… I’d rather be

A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn;

Wordsworth would prefer being a pagan who lived in harmony with Nature and accorded it respect and profound appreciation, than be ‘civilised’ and have no time for Nature and be engaged in destroying Nature.

Modern society has embraced the power of ‘Getting and spending,’ even more intensely.

We are engaged constantly in ‘getting and spending’ on Amazon, and staring at our mobile phones. Gone is the pleasure of listening to bird calls and watching the scenes of Nature unfurl across the seasons. So glued is our vision to the near field of a mobile phone, that our eyes rarely wander to the far field of trees, clouds, flowers, and the blessed earth.

We at KRG may not have stopped taking down a book to read, but even the pleasure of holding a book is being replaced by a Kindle or iPad.

Joe thought he’d rewrite this poem of Wordsworth with a few changes for the 21st century. Kavita said it would be good to hear Joe’s take. Here it is:

Joe’s version:

The World Is Too Much With Us

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending at Amazon’s site

What we see is a perpetual blight;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

This Sea that bares her bosom to the moon;

Bargains and returns we search at all hours

Fill our homes with goods, one then has to scour;

For this, for everything, we are out of tune;

It moves us not. Great God! I’d rather be

A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

So might I sitting in my cheerful flat

Watch glimpses of Nature, not my mobile,

Have sight of birds and engage in chit-chat

With solitary lass, warm and nubile.

KumKum

KumKum chose the poem Fare Thee Well by Lord Byron. George Gordon Lord Byron, aka Lord Byron, was born on Jan 22, 1788 in London, England and he died at age 36 in Missolonghi, in Greece on April 19 1824. Lord Byron was one of the major Romantic poets of English Literature. His poetry dealt with the themes of love, death, nature, and morality.

There is a fairly long biography of George Gordon Lord Byron at KRG’s 2017 Romantic Poets session with a portrait of him in Albanian dress. Byron is revered in Greece because he fought for the freedom of Greece, then occupied by the Ottoman Empire. Byron died in 1824 at Messolonghi in Western Greece on April 19. The Greek government in 2008 declared this day Byron Day and stated that the initiative would burnish the memory of ”a man who believed deeply in democratic values and Hellenism.” Statues of Byron are scattered all over Greece.

Byron statue depicting Greece in the form of a woman crowning him.– Athens, Greece, outside the National Garden. The statue is by the French sculptors Henri-Michel Chapu and Alexandre Falguière

Fare Thee Well is a fifteen stanza poem composed after his separation from his wife Anne Isabella Milbanke. She was brought up to be concerned for the workers and tenants of her parents’ estate and helped establish a school in Seaham. An early reader, Annabella Milbanke was especially interested in mathematics and astronomy, which she studied with a Cambridge tutor.

Annabella Isabella Milbanke by Charles Hayter (1812)

The poem is composed in the pattern ABAB. In this poem Byron, rather unapologetically bids his wife and baby daughter farewell. In two stanzas of this poem, the poet very tenderly expresses his sorrow of being separated forever from his daughter. The other stanzas are addressed to his estranged wife, where he blames the wife equally for his misfortune. Somewhere in the poem Byron admits his faults, but then he goes on to write,

Though the world for this commend thee --

Though it smile upon the blow,

Even its praise must offend thee,

Founded on another's woe:

Though my many faults defaced me,

Could no other arm be found,

Than the one which once embraced me,

To inflict a cureless wound?

The poet writes the above lines almost absolving his fault.

But, KumKum said the distressed heart of a father is revealed in these touching lines of the poem:

And when thou wouldst solace gather,

When our child's first accents flow,

Wilt thou teach her to say "Father"?

Though his care she must forego?

This is an autobiographical poem of Byron that exudes his romantic visions and descriptions. Byron's autobiographical poem Childe Harold's Pilgrimage (1812-1818) is a better appreciated poem. On another occasion Joe read a 500-word excerpt from that poem, concerning Byron’s daughter Ada, whom he had by Annabella Milbanke. Whatever you may say about Byron as a man, he had a great fondness for Ada. This was the girl who became Ada Lovelace, the woman who is credited today for being the first programmer of computers, under the tutelage of Charles Babbage who invented the Difference Engine.

The London Science Museum's difference engine, the first one actually built from Babbage's design

Byron’s poem Fare Thee Well was written when he separated from his first wife, Anne Isabella Milbanke. The poem shows his sadness at this separation from his wife and child, but he's not apologising for it.

Perhaps it was she who left him and not vice versa. She left him, obviously, because he was having an affair. Byron had so many affairs, that it would have been difficult for a respectable woman to stay with a man who was not faithful; but he pretends, well, that's me. He implies she should have stayed on.

The child from this union also got separated from Byron – it was Ada Lovelace, who is given credit along with Charles Babbage for a mechanical version of the modern day computer, called The Difference Engine. Ada Lovelace lived long, and she was a brilliant woman.

Byron had another child, by one of his mistresses, Claire Clairmont, the step-sister of Percy Shelley’s wife Mary Shelley. But that child, Allegra, only lived till age five.

Byron

Joe said in this poem Byron is really talking about his child, not about the woman he's separated from, because throughout the poem, he's talking about the little daughter of his he is leaving behind:

And when thou wouldst solace gather,

When our child’s first accents flow,

Wilt thou teach her to say “Father!”

Though his care she must forego?

When her little hands shall press thee,

When her lip to thine is pressed,

Think of him whose prayer shall bless thee,

Think of him thy love had blessed!

Should her lineaments resemble

Those thou never more may’st see,

Then thy heart will softly tremble

With a pulse yet true to me.

It's really about the daughter he's missing that he's writing this poem, entirely animated by a father’s love, not husband’s love for his wife. He's not remembering his wife so much, according to Joe.

KumKum said Byron keeps on insisting that it was Milbanke who left him, and though the society may praise her, she has done something wrong, according to Byron. He didn't much care for his wife, KumKum said. But the words of final separation are emphatic:

Fare thee well! thus disunited,

Torn from every nearer tie.

Seared in heart, and lone, and blighted,

More than this I scarce can die.

He's talking about his relationship to his wife too.

Would that breast were bared before thee

Where thy head so oft hath lain,

While that placid sleep came o’er thee

Which thou ne’er canst know again:

Would that breast, by thee glanced over,

Every inmost thought could show!

Then thou wouldst at last discover

‘Twas not well to spurn it so.

Byron is just reminding, look, all these we did, and you should have stayed on. He really thought his wife would stay on with the child, and he could continue having his affairs. It doesn't happen that way. She was a very strong woman.

The poem Fare Thee Well also has an epigraph, consisting of 15 lines from the poem Christabel by Coleridge, which KumKum did not read to save time. Poets and novelists often use an epigraph before their own work to explain the theme of the poem or book, or a chapter of the book. T.S. Eliot was famous for that.

The epigraph from the poem Christabel reflects Byron’s theme: the sorrow of parting. Christabel concerns two women – Christabel the protagonist who meets Geraldine. They separate by an unusual circumstance, and that parting is recalled in these poignant lines:

And to be wroth with one we love,

Doth work like madness in the brain;

Alexander Pushkin (another famous Romantic Poet) in turn quoted the opening lines of Byron’s poem as an epigraph to the final chapter of his own long poem, Evgenii Onegin:

Fare thee well, and if for ever

Still for ever fare thee well.

Pamela

Pamela was also taking off from William Wordsworth. She added a few more things to what Kavita told about the poet. Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge launched the Romantic Era of the British poetry. His wife (Mary Hutchison) was 12 years younger to him. William Wordsworth died in April 1850 and Mary his widow followed him nine years later. She published his lengthy autobiographical Poem to Coleridge as The Prelude several months after his death. Though it failed to interest people at the time, it has since come to be widely recognised as Wordsworth’s masterpiece.

Wordsworth

Wordsworth had five or six children; the last was also named William Wordsworth. He's known for Lyrical Ballads, co-authored with Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Wordsworth's deep love for beauty in the natural world was established very early. Take one of his famous poems, I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o'er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

The inspiration for this poem came from a walk Wordsworth took with his sister Dorothy around Glencoyne Bay, Ullswater, in the Lake District. He would draw on this to compose I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud in 1804, inspired by Dorothy's journal entry describing the walk near a lake at Grasmere in England, where she writes;

“I never saw daffodils so beautiful they grew among the mossy stones about and about them, some rested their heads upon these stones as on a pillow for weariness and the rest tossed and reeled and danced and seemed as if they verily laughed with the wind that blew upon them over the Lake, they looked so gay ever glancing ever changing.”

Wordsworth explains in the Prelude that a love of nature can lead to a love of humankind. Pamela said she can see that in KumKum, how much she loves nature. All of us at KRG do, KumKum responded. We are nature lovers. Devika longs to go to Wayanad for instance, KumKum said.

Pamela chose The Mad Mother by Wordsworth because as a teacher at Delta Study school during parent-teacher meetings, she would meet a lot of ‘mad mothers,’ who thought their children were far more capable than they actually were, and who expected so much more from their children than they were actually capable of.

This was crazy, Pamela used to think. But Mothers who have exaggerated ideas of their children are not possessed of the kind of madness that William Wordsworth had in mind for ‘The Mad Mother.’ He has written just two poems based on maternal passion, one is called The Idiot Boy, and this one, The Mad Mother.

The Mad Mother focuses on a woman whose husband abandoned her and her newborn; she copes with this new reality and her own apparent insanity. What can we learn about motherhood from an insane, abandoned, wild mother?

‘Her eyes are wild,’ the poem starts. Did she fear the child also had a little madness? She's our mad, my pretty lad. Of course, the father is gone. It’s a sad poem. Does she feel a sense of fear that her child would inherit her own madness?

But if she writes so well, she can't be mad. She sounds very sensible. She was a poet. That's why they called her mad, maybe.

I'll teach my Boy the sweetest things;

I'll teach him how the owlet sings.

My little Babe! thy lips are still,

And thou hast almost sucked thy fill.

Joe said this is a failure of Wordsworth to characterise the mother’s madness as distinct from her poetry which is all a Wordsworth composition. It is not the mother talking.

Obviously, a mad woman would have phrased this differently. The diction of a truly mad mother would be full of shrillness and bursting out and suddenly going off key, said Joe. There isn't a single off key thing in this poem. It is all precisely rhymed.

KumKum suggested they called her mad because she was a poet. She was mad about her child. The child is described as a madman's baby. But that part is so beautiful, the way she describes how she feels about the baby.

After many years Pamela experienced holding a baby when the first grandchild came. It is such a lovely feeling, she exclaimed, the small baby hands around your neck. The warmth and the love of the baby is so sweet.

Saras reminded readers there is a thing called post-partum depression. It could be that the ‘mad mother’ is merely depressed. Those days, they would consider it madness. Some women experience the “baby blues” within a few days of giving birth, which can include feeling sad, worried, or tired. For many women, these feelings go away in a few days.

In those days, it was very easy to leave a wife. That complicated the issue for this mad mother. Saras said you could just declare wife insane, and the husband could walk away. Even now, it's very easy. Nothing has changed. And now, you have live-in partners, Pamela said. I’s so easy to walk out of a union.

There is actually no evidence of madness here; the only place where the word is used is in the first line.

Her eyes are wild, her head is bare,

What about this one:

A fire was once within my brain;

And in my head a dull, dull pain;

Probably she has post-natal depression, and she's been branded as mad.

Priya

The poem that Priya selected is an excerpt from Book 3 of Endymion, a thousand-line poem.

John Keats was born on October 31st, 1795 in London. He was the oldest of four children. His father was an a livery stable keeper, but he lost his parents early on. Keats himself died at a young age of 25. In that very short life he produced some of the most intense and beautiful romantic poetry.

He was a very good student, and studied to become a surgeon; he qualified but he did not practice, and he changed his line to writing poetry. It brought a lot of criticism from his family.

And when he started writing poetry people could see that where his talent lay, even from his initial works like the sonnet O Solitude (O Solitude! if I must with thee dwell,), and On First Looking into Chapman's Homer.

He dedicated the rest of his very short life to writing poetry. In 1818, he wrote Endymion. These are the years which were really productive, where he wrote his most famous sonnets, and even epic poems like Hyperion and Endymion. Endymion received positive and negative criticism. It was so harshly reviewed by Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine that Lord Byron was prompted to write that the sensitive Keats had been “snuffed out by an article.” John Gibson Lockhart, the critic, took jabs at Keats’ education, his middle-class upbringing, and even his former career as a licensed apothecary. “It is a better and a wiser thing to be a starved apothecary than a starved poet; so back to the shop Mr. John, back to plasters, pills, and ointment boxes.” – this was a bitter pill.

John Keats, though, realised where his talent lay. He was scholarly, because it was the Romantic time, the period where poets alluded to Greek literature, and the Renaissance. Keats's poem is rich in such lore. It is intense in emotions, and shows striking imagination, which the Romantics prized.

Endymion opens with the most famous lines of Keats:

A thing of beauty is a joy for ever:

Its loveliness increases; it will never

Pass into nothingness; but still will keep

A bower quiet for us, and a sleep

Full of sweet dreams, and health, and quiet breathing.

His poetry at that time was criticised as the Cockney school of poetry by J. W. Croker in the Quarterly Review. Such sharp and needless criticism his works got.

Keats spent the summer of 1818 on a walking tour in Northern England and Scotland, returning home to care for his brother. Keats himself, like his younger brother Tom, died of consumption.

He was writing poetry all the while. His love affair with Fanny Brawne beginning in 1818 was unconsummated and set aside by his own death. However, it inspired his work with well-known poems, including Bright Star, The Eve of St. Agnes, and Ode to a Nightingale.

Keats’ letters to her are worth reading for the intensity of passion and feeling they bring out.

Keats went to Rome on the advice of doctors who thought the Italian climate might prolong his life; but he died within 3 months of arriving there, on February 20th, 1821 at the age of 25. He was buried in the Protestant cemetery.

Before she read the poem, Priya said a little about the story of Endymion. John Keats dedicated this poem to the late Thomas Chatterton, another poet who died young, his life ending in suicide at age 17.

Endymion is written in rhyming couplets in iambic pentameter, also known as heroic couplets. Keats based the poem on the Greek myth of Endymion, the shepherd beloved of the moon goddess Selene. It comprises a thousand lines and is divided into four books. The part Priya read was from book three.

The story is about the shepherd in love with Cynthia, the moon, or Selene, the moon goddess. It is quite fantastic, and the story in verse goes through many twists and turns. In book three, the shepherd goes into a deep slumber, in which he dreams about meeting an old man who's got a thousand-year curse on him. Then he falls in love with an Indian girl and Cynthia is very sad to see that the shepherd has gone away with this Indian girl. Finally, that Indian girl is revealed as Cynthia herself in a different form. And they are happily united.

Priya went on to read the poem.

Endymion is telling the moon that he's found someone else, but don't go away. Just be there for him. Because he wants to love and live. And the moon is a perpetual love.

The last two lines are beautiful, said Pamela:

My sovereign vision.—Dearest love, forgive

That I can think away from thee and live!—

This is when he would have fallen in love with that Indian girl. And the Moon was very upset about it. But that Indian girl is none else but the Moon dressed as the Indian girl.

The readers were entranced by the poem. Priya was inspired, of course, by the KRG readers when they went to view the full moon on Cherai Beach and chilled out at Chili Out Cafe on Feb 25, 2024.

Saras

Felicia Dorothea Hemans Bio (25 September 1793 – 16 May 1835)

Hemans was an English poet (who identified as Welsh by adoption). Regarded as the leading female poet of her day, Hemans was immensely popular during her lifetime in both England and the United States, and was second only to Lord Byron in terms of sales of poetry.

Two of her opening lines, "The boy stood on the burning deck" and "The stately homes of England", have acquired classic status.

Felicia Dorothea Browne was the daughter of George Browne and Felicty Wagner. Her father worked for his father-in-law's wine importing business and succeeded him as Tuscan and imperial consul in Liverpool. Hemans was the fourth of six children (three boys and three girls) to survive infancy. Her sister Harriet collaborated musically with Hemans and later edited her complete works (7 vols. with memoir, 1839). George Browne's business soon brought the family to North Wales, where she spent her youth. She later called Wales "Land of my childhood, my home and my dead".

Hemans was proficient in Welsh, French, German, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese. Her sister Harriet remarked that "One of her earliest tastes was a passion for Shakespeare, which she read, as her choicest recreation, at six years old."

Hemans’ first poems, dedicated to the Prince of Wales, were published in Liverpool in 1808, when she was fourteen, arousing the interest of poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, who briefly corresponded with her. She quickly followed them up with England and Spain (1808), politically addressing the Peninsular War, and The Domestic Affections (1812). In contrast to its title, which Hemans did not choose, many of the book's poems explore issues of patriotism and war.

Hemans’ major collections, including The Forest Sanctuary (1825), Records of Woman and Songs of the Affections (1830) were highly popular. Hemans published many of her pieces in magazines first, enabling her to remain in the public eye and adapt to her audience, as well as earning additional income. Many of her pieces were used for schoolroom recitations and collections were presented as school prizes, especially to female readers.

Her last books, published in 1834, were Scenes and Hymns of Life and National Lyrics, and Songs for Music. It has been suggested that her late religious poetry, like her early political poetry, marks her entry into an area of dispute that was both public and male-dominated.

At the time of her death in 1835, Hemans was a well-known literary figure, highly regarded by contemporaries, and with a popular following in the United States and the United Kingdom. Both Hemans and Wordsworth were identified with ideas of cultural domesticity that shaped the Victorian era.

Felicia Hemans

In 1812, Felicia Browne married Captain Alfred Hemans, an Irish army officer some years older than herself. During their first six years of marriage, Hemans gave birth to five sons, and then the couple separated. Marriage had not, however, prevented her from continuing her literary career. Several volumes of poetry were published by the respected firm of John Murray in the period after 1816, beginning with The Restoration of the Works of Art to Italy (1816) and Modern Greece (1817). The collection Tales and Historic Scenes came out in 1819, the year of the Hemans' separation.

One of the reasons why Hemans was able to write so prolifically as a single parent, was that many of the domestic duties of running a household were taken over by her mother, with whom she and her children lived. It was a financial necessity for Hemans to write to support herself, her mother, and the children. On 11 January 1827, Hemans' mother died, leading to the breaking up of the household. Hemans sent her two oldest sons to Rome to join their father, and moved to a suburb of Liverpool with her younger sons.

From 1831, Hemans lived in Dublin, which was recommended as healthier than Liverpool. Despite the change, she continued to experience poor health. She died on 16 May 1835. She was buried in St. Ann's Church, Dawson Street, Dublin.

Hemans' works appeared in nineteen individual books during her lifetime, publishing first with John Murray and later with Blackwoods. After her death in 1835, her works were republished widely, usually as collections of individual lyrics and not the longer, annotated works and integrated series that made up her books. She was a valued model for surviving female poets, such as Caroline Norton, Letitia Elizabeth Landon, Lydia Sigourney and Frances Harper, the French Amable Tastu and German Annette von Droste-Hülshoff. To many readers she offered a woman's voice confiding a woman's trials; to others, a lyricism consonant with Victorian sentimentality and patriotism. In her most successful book, Records of Woman (1828), she chronicles the lives of women, both famous and anonymous. Portraying examples of heroism, rebellion, and resistance, she connects womanhood with “affection's might.”

Hemans' poem The Homes of England (1827) is the origin of the phrase ‘stately home’, referring to an English country house.

Despite her illustrious admirers her stature as a serious poet gradually declined, partly due to her success in the literary marketplace. Her poetry was considered morally exemplary, and was often assigned to schoolchildren; as a result, Hemans came to be seen as more a poet for children rather than a serious author. Schoolchildren in the U.S. were still being taught The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers in New England in the middle of the 20th century. But by the 21st century, The Stately Homes of England refers to Noël Coward's parody, not to the once-famous poem it parodied.

With the rise in women's studies, Hemans’ critical reputation has been re-examined. Her work has resumed a role in standard anthologies and in classrooms and seminars and literary studies, especially in the US. Anthologised poems include The Image in Lava, Evening Prayer at a Girls' School, I Dream of All Things Free, Night-Blowing Flowers, Properzia Rossi, A Spirit's Return, The Bride of the Greek Isle, The Wife of Asdrubal, The Widow of Crescentius, The Last Song of Sappho, Corinne at the Capitol and The Coronation of Inez De Castro.

First published in August 1826 the poem Casabianca (also known as The Boy stood on the Burning Deck) was another of Hemans popular poems and depicts Captain Luc-Julien-Joseph Casabianca and his 12-year-old son, Giocante, who both perished aboard the ship Orient during the Battle of the Nile. The poem was very popular from the 1850s on and was memorised in elementary schools for literary practice.

Martin Gardner included Casabianca in his collection of Best Remembered Poems, along with a childhood parody. Michael R. Turner included it among the "improving gems" of his 1967 Parlour Poetry. Others wrote modern-day parodies that were much more upbeat and consisted of boys stuffing their faces with peanuts and bread. These contrast sharply with the dramatic image created in Hemans' Casabianca.

Several of Hemans's characters take their own lives rather than suffer the social, political and personal consequences of their compromised situations. At Hemans's time, women writers were often torn between a choice of home or the pursuit of a literary career. Hemans herself was able to balance both roles without much public ridicule, but left hints of discontent through the themes of feminine death in her writing. The suicides of women in Hemans's poetry dwell on the same social issue that was confronted both culturally and personally during her life: the choice of caged domestication or freedom of thought and expression.

The Bride of the Greek Isle, The Sicilian Captive, The Last Song of Sappho and Indian Woman's Death Song are some of the most notable of Hemans’ works involving women's suicides. Each poem portrays a heroine who is untimely torn from her home by a masculine force – such as pirates, Vikings, and unrequited lovers – and forced to make the decision to accept her new confines or take command over the situation. None of the heroines are complacent with the tragedies that befall them, and the women ultimately take their own lives in either a final grasp for power and expression or a means to escape victimisation.

Source : Wikipedia

Saras read a poem by Felicia Hemans. She was one of the first women to write a book, and one of the very few women poets of the Romantic era. But unfortunately she's gone out of fashion and she's not so popular anymore. But in those days she was second only to Byron in the sales of her books.

Saras was a bit surprised when she read that. But you can see clearly the difference of standard between her work and that of Byron.

Saras cast a brief view on her life: she was born in 1793, and died in 1835 at the age of just 42. She was regarded as one of the leading female poets of her time, immensely popular both in England and in the US. She's most famous for the poem which many of us would have read in school called Casabianca, a poem about a boy sailor named Louis de Casabianca who remains on a burning deck during the Battle of the Nile. The poem's opening lines are famous:

The boy stood on the burning deck,

Whence all but he had fled;

The flame that lit the battle's wreck,

Shone round him o'er the dead

Everybody in India and England has been exposed to that in school at a tender age. Pamela said it left a lasting impact because you were so young at that time.

Another of her poems is called the The Homes of England:

The stately homes of England

How beautiful they stand!

Amidst their tall ancestral trees,

O'er all the pleasant land!

These two poems of hers are still widely read. She was born in Liverpool and then moved to Wales. Her father was a wine merchant and also politically aware and active.

Hemans spoke a many languages. Apart from English, she spoke Welsh, French, German, Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese. Wow! – said somebody.

As a six-year-old she would read Shakespeare as recreation – this is according to her sister who wrote a biography of Felicia Hemans after her death and published some of her poems. Clearly, she was very intelligent. Her first poem was published in 1808 and it caught the interest of Shelley, who corresponded with her.

She married an Irish army officer, Alfred Hemans, and had five children by him but she separated after six years. He went off to Italy in 1818 and never came back. Hence she was forced to support herself and writing poems was her ticket. She would publish her poems in magazines first so that she remained in the public eye, and then publish her collections as books.

She also wrote against the wars that were being fought. At that time England was fighting wars both in America and in Europe against Napoleon. But being against war was considered unpatriotic.

Later in life, a lot of her poetry turned to spiritual matters. A criticism against her poetry is that she is very dramatic – too dramatic for moderns.

Saras had a choice between Casablanca and The Spanish Chapel. She decided on the latter as the less familiar poem, which she proceeded to read.

Death became a theme for Hemans in later life. She wrote about female suicide. Three or four of her poems specifically mention abandonment by men and after that the heroine of the poem commits suicide. That was probably a reflection of her own experience, since she was abandoned by her husband. Those times were also difficult – women were often left to fend for themselves and men had things easy, as usual.

In the stanza:

“Alas!” I cried, “fair faded thing!

Thou hast wrung bitter tears,

And thou hast left a wo, to cling

Round yearning hearts for years!”

what is the meaning of ‘wo’? Saras supposed it was ‘woe’ the poet meant and the spelling was not corrected, but left as the poet wrote it. Another interpretation is that ‘wo’ is Old English, a variant of ‘wough’, meaning ‘Wrong, evil; injury, harm.’

Shoba

Shoba read the same poet as Devika who already gave her bio. Mary Robinson was just 43 years when she died in 1800, so she was one of the earlier romantic poets, and her style, even in the one Devika read, feels quite modern. She's appreciating the beauty of the African and the Indian skin, besides extolling British women as the most good looking, as the title says. But then she goes on to appreciate women of different countries as women who are also beautiful.

Mary Robinson too was very beautiful, as one can see in the portrait by Joshua Reynolds:

Mary Robinson known as Perdita (‘the lost one’), portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1782

The words ‘ busy sounds, noisy London, shrilly bawls, milk pail rattles, tinkling bell, noisy trunk makers and knife sharpeners, tinmen, squeaking cork cutters, cries of vendors … all express the the din, hustle and bustle of a London street at the close of the eighteenth century. The poet mentions the smart damsel sitting in a shop and another shop selling pastries. Mary Robinson died in 1800 before the discovery of petroleum or gas. Most of the jobs then, are unfamiliar to us now as they don’t exist anymore.

She describes a London summer morning, and we see all the colour and the sound that is there on the streets of the city, and the different professions at work. Shoba had to google and find what a pot-boy does. A pot-boy serves drinks at a tavern, and then there's the cooper, one who repairs barrels, and the cork cutter who cuts sheets of cork for bottle stoppers.

The city of Hull in England, an early whaling port, had streetlights by 1713. By 1750 London had almost 5000 streetlights, burning whale oil.The first (coal-) gas lights were lit on Dec 31 1813.

All these trades are being plied by the roadside, and the poet is observing. These are the jobs of 250 years ago, which we have to google to find out.

Probably 200 years from now, or maybe even 100 years from now, they'll be googling (if Google search exists), to know what we did, and all the professions now in play – many of which could be obsolete in a 100 years.

The band-box that a young lady holds is cylindrical, made of thin wood or card board and used to hold hats and collars that needed to maintain their shape. BandBox is the name of a dry cleaning service in India. The lamp-lighter climbs a tall ladder to trim the half filled lamp. The city of Hull in England, an early whaling port, had streetlights by 1713. By 1750 London had almost 5000.

Hackney-coaches, wagons and carts moved by horses filled the road with sound and smell. If the poet were to time travel to a present day London Highway, she would find it a magical land with humans carrying a magical wand in their pocket and streetlights, burning whale oil. The first gas lights were lit on Dec 31 1813.

Shoba read the poem and everyone exclaimed that a lovely winter morning vision. We can see the whole day go by in the city and almost feel the breeze.

KumKum recalled how in some Calcutta streets women hawkers would cry out their trade which was to to buy your old saris. Here there is mention of the washing of streets. In Calcutta, the roads would be washed every morning because the horse gharries used to ply, and there was a lot of horse dung.

Thomo mentioned that it was a common sight in Calcutta to see corporation workers at dusk carrying a ladder to climb and turn on the gas lights on the streets. Gas lamps were first lit in 1857 in Calcutta from coal gas distributed by the Oriental Gas Company whose production plant was in Howrah. Calcutta also had the feature of water from the Hooghly river being pumped under pressure so that the streets could be washed every morning by corporation workers. These were the same water hydrants used for firefighting with fire trucks providing the extra pressure. All this is no more. Gas lights are gone and washing the streets is no more done. The first street of Calcutta to be lit by electricity was Harrison Road (now Mahatma Gandhi Road) between 1889 and 1892.

Joe also mentioned the trade of the ‘bhisti’ in Calcutta in the old days (fifties). A bhisti was a water carrier, delivering drinking water to people’s homes and businesses, where there was no piped water supply; they were crucial to the city's daily life, carrying water in leather pouches and providing it to residents on demand, especially during hot weather. They sprinkled the roads, brought drinking water to the people, filled their baths, and in time of war, carried the cooling draught to the wounded. Yes! The Bhistis were an integral part of the Supply and Transpot Corps of the British Indian Army. Recall Kipling’s poem Gunga Din:

The finest man I knew

Was our regimental bhisti, Gunga Din,

He was ‘Din! Din! Din!

‘You limpin’ lump o’ brick-dust, Gunga Din!

‘Hi! Slippy hitherao

‘Water, get it! Panee lao,

‘You squidgy-nosed old idol, Gunga Din.’

Thomo

William Cullen Bryant Bio

William Cullen Bryant, 1878. Oil on canvas, painted by Wyatt Eaton (Brooklyn Museum)

William Cullen Bryant was born in Massachusetts on 3rd November 1794. He started his career as a lawyer but showed an interest in poetry early in his life and was categorised as an American romantic poet.

In 1825, Bryant relocated to New York City, where he became an editor of two major newspapers including the New York Evening Post of which he was a long time editor. Bryant also emerged as one of the most significant poets in early America and has been grouped among the Fireside Poets. The Fireside Poets were a group of five 19th-century American poets who were popular with both general readers and critics:

⁃ Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

⁃ William Cullen Bryant

⁃ John Greenleaf Whittier

⁃ Oliver Wendell Holmes

⁃ James Russell Lowell

These poets were very accessible and popular among readers and critics both in the United States and overseas. Their domestic themes and messages of morality presented in conventional poetic forms deeply shaped their era; the decline in their popularity at the beginning of the 20th century.

Bryant died on 12th June 1878.

The two poems Thomo chose were:

1. Blessed Are They That Mourn

Bryant rejected the prevailing Christian idea of the afterlife and displayed instead a pagan, stoic, and pantheistic faith.

The poem which was written, when he was only 17 years old, explores the concept of finding solace and hope in times of grief and adversity. It suggests that those who endure suffering are not to be pitied, but rather blessed, as their pain will ultimately lead to greater happiness.

Shoba commented on the lines:

And grief may bide an evening guest,

But joy shall come with early light.

That joy comes in the morning, isn't that line in Shakespeare also, asked Shoba? Nobody could say, but Joy in the Morning is a novel by P. G. Wodehouse, first published in the United States on 22 August 1946.

There is a novel by that name by Betty Smith.

2. No Man Knoweth His Sepulchre

This poem explores the idea that God protects the graves of the righteous, even when their burial places are unknown. The reference is clearly about Moses who “aroused the Hebrew tribes to fly.” The poem also suggests that the wicked will not have the same protection, and their graves will be trampled and forgotten.

Moses never saw the promised land. Someone asked what or who is Moab in the poem? Moab is a Hebrew tribe, the tribe of Cain, a Cannanite

The Israelites were constantly fighting with them and still continue to fight with them. The poem says that the wicked will not have the same protection, and their graves will be trampled and forgotten. This is one of the few poems of Bryant with a religious flavour. Very much a religious flavour, said KumKum.

Zakia

Zakia read a Keats sonnet, and thanked Joe for helping her out, She considers herself enriched at this romantic poet session, but was a bit intimidated, not knowing what to read and so sought help. It’s a sonnet which Keats wrote to Byron. Everyone has spoken about Keats.

Now a bit about Byron and Keats; in a letter to his brother George, Keats had written, shortly after the publication of Byron’s Don Juan (cantos I-II), in 1819:

‘You speak of Lord Byron and me – There is this great difference between us. He describes what he sees – I describe what I imagine – Mine is the hardest task’.

Keats suggests, Byron is a poet of the ‘real world’, the actual and the factual, and he wrote of things clearly manifest to the senses. Byron writes as he sees, about what he sees. Keats on the other hand is writing from his imagination; the originality comes from his creative imagination, and that Keats suggests is more profound.

There was a lot of rivalry between them because Byron was a flamboyant and a handsome nobleman whose wit, charm and ancestral title accorded him entry into the most elite circles of English society, while Keats was a poor and struggling middle-class poet whose work was often savaged by the prominent critics of the day. They argued that poetry was the province of the educated elite such as Byron, and considered Keats a “cockney” poet.

But Keats’ poems remain amongst the most widely analysed in English literature, in particular Ode to a Nightingale, Ode on a Grecian Urn and On First Looking into Chapman's Homer. His letters too are a treasure for those who want to understand poetry.

Zakia felt the sonnet she read was beautifully worded. He was so young when he wrote all the sonnets. One could not imagine that he had so much of sensibility and writing genius. She then recited the sonnet which begins:

Byron! how sweetly sad thy melody!

Attuning still the soul to tenderness,

Byron had a lot of sad incidents in his life; he had a clubfoot, he had to separate from his wife; then a child of his was lost, and he had many failed relationships, much of it through his own fault..

There was a rivalry between Keats and Byron, friendly as far as we know. Keats could not be vicious at all. Perhaps Byron could be. He was not a nice man, said Saras, very good looking though. He had money and he could be grandiose but often used his money for good purposes. Byron might have been condescending about Keats, but he really thought Keats was a poet of quality.

Joe said authors and poets particularly should remember that their reputation is not made in their lifetime. Whether they will be remembered or not, will be decided long after they are gone. But it's not for us to rank the big six Romantic poets, although each of us will have in our own mind who we think among Blake, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shelley, Keats, and Byron, as our favourite.

Byron was a great advocate of Greek emancipation from the Ottoman Empire. The Greeks have started a special day in Greece to remember him. Yes, he's considered a big hero in Greece, chimed in Saras. He helped them, and financed an army to help them fight for independence, and he died there from improper blood-letting for a mosquito bite.

Zakia said Keats didn't have any big expectations that he was going to be remembered. When he was buried in Rome's Protestant Cemetery, his grave marker bore the epitaph “Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water.” He didn't believe he wrote anything lasting.

He was only 25, and even when he wrote Endymion, people criticised the poem. And Keats, instead of defending himself, Priya noted, agreed it was not such a good work, after all. A thing of Beauty maybe, but not a joy for ever.

All romantic poets died young, except Wordsworth. Wordsworth was 80 years old when he died. It was a long life particularly for those days when 40 or 50 was the life expectancy, said Saras. A great many women died in childbirth.

Kavita mentioned that she recited Wordsworth’s “Daffodils” poem, titled I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud, on her first joining KRG. It was directly inspired by an entry in his sister Dorothy Wordsworth's journal where she described seeing a field of daffodils “dancing” in the breeze during a walk in the Lake District, which she recorded on April 15, 1802; Wordsworth later incorporated this vivid imagery in his poem. Read the entry on Dorothy’s journal of April 15, 1802:

“When we were in the woods beyond Gowbarrow Park we saw a few daffodils close to the water-side. We fancied that the sea had floated the seeds ashore, and that the little colony had so sprung up. But as we went along there were more and yet more; and at last, under the boughs of the trees, we saw that there was a long belt of them along the shore, about the breadth of a country turnpike road. I never saw daffodils so beautiful. They grew among the mossy stones about and above them; some rested their heads upon these stones, as on a pillow, for weariness; and the rest tossed and reeled and danced, and seemed as if they verily laughed with the wind, that blew upon them over the lake; they looked so gay, ever glancing, ever changing.”

Wordsworth does not acknowledge his debt to Dorothy’s keen observation and poetic expression, although it was upon reading it that he was inspired to write his well-known poem. It was not Nature, but Dorothy who inspired him. His sister supplied almost all the words, including the dancing of the daffodils.

Misappropriation, at the very least, wouldn’t you say?.

If we write a journal, our children will throw out the diaries. What rubbish! – they will say. Now we are all writing notes on the phone – notes that are very transitory. Should we not start writing in a journal?

Kumkum describes her days, even when she's in Cochin, describing the evenings so that her grandchildren abroad can picturise her life here. This stuff we write on mobile phones goes into the cloud and we don't know where it goes after that or how long it will remain once our Google or iCloud subscriptions end.

But if you journalise it in a real book, anybody can pick it up and read. KumKum was writing today and felt it was just not clear to her eyes anymore.

Our next meeting is on September 24th. Priya will join by 6:30pm as it is a work day for her; she’s on duty.

KumKum expected to be back from USA for an October celebration of the birthdays of three readers. Maybe Priya will cater food from her Bihari kitchen.

Joe said Thomo mentioned in his poem about Moab, M-O-A-B. Moab is the region which is described in the Bible. It is present day Jordan, East of the Dead Sea. In ancient times it competed militarily and politically with Israel. Both King David and Jesus are descendants of a Moabite, a woman called Ruth, very famous in the Bible, for her devotion, faith, and exemplary character. There is even a feminine: Moabitess..

Moabites and Israelites could barely understand each other's languages. And their customs were distinct.

Someone said I don't think now they understand each other at all or don’t want to. Joe responded now they do because the other meaning of Moab, M-O-A-B is Mother Of All Bombs, the only language the world understands.

Consolidated Poems for Romantic Poets reading on Aug 19, 2024

Arundhaty

How Do I Love Thee? (Sonnet 43) by Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806 – 1861)

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and ideal grace.

I love thee to the level of every day’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candle-light.

I love thee freely, as men strive for right.

I love thee purely, as they turn from praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood’s faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints. I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life; and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

Devika

Lines on hearing it declared that no Women were so handsome as the English by Mary Robinson

BEAUTY, the attribute of Heaven!

In various forms to mortals given,

With magic skill enslaves mankind,

As sportive fancy sways the mind.

Search the wide world, go where you will,

VARIETY pursues you still;

Capricious Nature knows no bound,

Her unexhausted gifts are found

In ev'ry clime, in ev'ry face,

Each has its own peculiar grace.

To GALLIA's frolic scenes repair,

There reigns the tyny DEBONAIRE;

The mincing step—the slender waist,

The lip with bright vermilion grac'd:

The short pert nose—the pearly teeth,

With the small dimpled chin beneath,—

The social converse, gay and free,

The smart BON-MOT—and REPARTEE.

ITALIA boasts the melting fair,

The pointed step—the haughty air,

Th' empassion'd tone, the languid eye,

The song of thrilling harmony;

Insidious LOVE conceal'd in smiles

That charms—and as it charms beguiles.

View GRECIAN MAIDS, whose finish'd forms

The wond'ring sculptor's fancy warms!

There let thy ravish'd eye behold

The softest gems of Nature's mould;

Each charm, that REYNOLDS learnt to trace,

From SHERIDAN's * bewitching face.

Imperious TURKEY's pride is seen

In Beauty's rich luxuriant mien;

The dark and sparkling orbs that glow

Beneath a polish'd front of snow:

The auburn curl that zephyr blows

About the cheek of brightest rose:

The shorten'd zone, the swelling breast,

With costly gems profusely drest;

Reclin'd in softly-waving bow'rs,

On painted beds of fragrant flow'rs;

Where od'rous canopies dispense

ARABIA's spices to the sense;

Where listless indolence and ease,

Proclaim the sov'reign wish, to please.

'Tis thus, capricious FANCY shows

How far her frolic empire goes!

On ASIA's sands, on ALPINE snow,

We trace her steps where'er we go;

The BRITISH Maid with timid grace;

The tawny INDIAN 's varnish'd face;

The jetty AFRICAN; the fair

Nurs'd by EUROPA's softer air;

With various charms delight the mind,

For FANCY governs ALL MANKIND.

Geetha

An Extempore Canto xii and xiii by John Keats

Canto xii.

When they were come into Faery’s Court

They rang — no one at home — all gone to sport

And dance and kiss and love as faerys do

For Faries be as human lovers true —

Amid the woods they were so lone and wild

Where even the Robin feels himself exil’d

And where the very books as if affraid

Hurry along to some less magic shade.

‘No one at home’! the fretful princess cry’d

‘And all for nothing such a dre[a]ry ride

And all for nothing my new diamond cross

No one to see my persian feathers toss

No one to see my Ape, my Dwarf, my Fool

Or how I pace my Otaheitan mule.

Ape, Dwarf and Fool why stand you gaping there

Burst the door open, quick — or I declare

I’ll switch you soundly and in pieces tear.’

The Dwarf began to tremble and the Ape

Star’d at the Fool, the Fool was all agape

The Princess grasp’d her switch but just in time

The Dwarf with piteous face began to rhyme.

‘O mighty Princess did you ne’er hear tell

What your poor servants know but too too well

Know you the three great crimes in faery land

The first alas! poor Dwarf I understand

I made a whipstock of a faery’s wand

The next is snoring in their company

The next the last the direst of the three

Is making free when they are not at home.

I was a Prince — a baby prince — my doom

You see, I made a whipstock of a wand

My top has henceforth slept in faery land.

He was a Prince the Fool, a grown up Prince

But he has never been a King’s son since

He fell a snoring at a faery Ball

Your poor Ape was a Prince and he poor thing

But ape — so pray your highness stay awhile

‘Tis sooth indeed we know it to our sorrow —

Persist and you may be an ape tomorrow —

While the Dwarf spake the Princess all for spite