The first image revealed by the Vera Rubin telescope shows the Trifid and Lagoon nebulae in the constellation Sagittarius 5,000 light years away. The stunning detail comes from its 3,600 megapixel camera

The W.B. Yeats statue by Rowan Gillespie in Sligo has Yeats's poems inscribed on it – over 150 "cuts" from his poems are imprinted in positive relief on the statue's surface. One notable inscription is "I made my song a coat"

KumKum introduced a new class of poems called Ekphrastic poems, which respond to a work of visual art, creating a dialogue between the written word and the image. She took a famous example by W.H. Auden depicting the Fall of Icarus in a painting by Pieter Brueghel. As it turned out the poem Joe read before her could also be classed as ekphrastic, because it takes off from the visual imagery of Marc Chagall’s paining Equestrienne of a girl riding with a boy on a white horse with a violin in its mouth.

Why do we advertise ourselves as “A group of readers of literature in English, poetry and fiction”? Is it because we wish to ignore other languages that flourish in India? Is it because our knowledge of other literatures is so slight that we dare not tread there?

Looking through the posts in our blog which have preserved a wealth of detail about our readings and discussions over the years, you will find poems and novels from five continents – exhibited in English translation. It is not that we are ignorant of the riches in the original. You will find in the blog original translations of verse from languages like Urdu, Hindi, and Bengali. Readers have sung ghazals. There are even original translations from French and Spanish. We encourage readers to read in the original language, so long as a translation is provided into English for common enjoyment.

At KRG we have a great desire to know and appreciate the vessels that hold human culture, of which language, music, and art form an irreducible distillate. For us language is the primary vehicle through which we engage in that quest; finding pleasure in it, we sprinkle it from time to time with music and art.

Kamala Das - popularly known by her pseudonyms Madhavikutty and Ami. She is prominent in Indian literature for her poetry and short stories

There is a trend now among prominent politicians exuding an illiberal brand of ultra-nationalism to assert that Indians speaking in English will soon be cowering in shame. Presumably, reading is still okay, and if so, one cannot do better than point them to Kamala Das who wrote her short stories in Malayalam under the pen name Madhavikutty, and her poems in English under her own name. Here’s how she refuted critics of English in her poem titled Introduction:

… Why not let me speak in

Any language I like? The language I speak,

Becomes mine, its distortions, its queernesses

All mine, mine alone.

It is half English, halfIndian, funny perhaps, but it is honest,

It is as human as I am human, don't

You see? It voices my joys, my longings, my

Hopes, and it is useful to me as cawing

Is to crows or roaring to the lions, it

Is human speech, the speech of the mind that is

Here and not there, a mind that sees and hears and

Is aware.

Full Account of the Poetry Session at KRG – June 20, 2025

Arundhaty

Arundhaty recited two poems by WB Yeats, The Lake Isle of Innisfree, and Aedh Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven.

That second one is beautiful. The narrator is the character Aedh. In the poem, he wishes to provide the most beautiful and valuable possessions, symbolised by the ‘cloths of heaven,’ to his lover. However, all he has to offer are his dreams, as he is poor. Aedh is a mythical character who appears in other works of Yeats (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aedh_Wishes_for_the_Cloths_of_Heaven)

Readers liked the poem.

William Butler Yeats, widely considered one of the greats of the English language, received the 1923 Nobel Prize for Literature

The first one, The Lake Isle of Innisfree, is very famous, said Joe. We all had it in our school or college. Joe said when he and KumKum visited the National Library of Ireland in Dublin, there are two very large exhibits, one of Yeats, and the other of Joyce. There were all sorts of historical artefacts and memorabilia displayed. And one set were recordings of Yeats on various occasions. This very poem was in the recorded voice of Yeats. He had a sonorous and ringing voice. He was on the older side when he was reciting it, but it was very nice to hear that voice.

If you want to listen to an analysis of this poem, then look up this penetrating talk by Dana Gioia, poet, literary critic, and essayist. Read to the end where he arrives at the crux of the poem by pointing out the allusion in the very first line.

Yeats statue by Rowan Gillespie in Sligo – over 150 "cuts" from his poems are imprinted in positive relief on the statue's surface

Devika

Luckily for her, Devika had written a bio many days ago before she was hospitalised. Now that she was well enough to be reciting with us, we heard her in her usual sprightly voice and welcomed her back to our fold.

She sat and wrote it one day when she had the time, never thinking she woukd be going into hospital for two weeks. KumKum said this is something Devika always does diligently. She is prepared. She is even ready with her Jane Eyre readings for July 14.

Devika finds nowadays, thanks to Joe and Kumkum and their family, there are so many books of poetry won as prizes that she doesn’t have to look at the Internet at all. She goes through those books to find her poem. Then she googles to get an online version and sends it to Joe, because she doesn’t then need to type out the entire poem.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Devika has never done Elizabeth Barrett Browning, so she thought, she’d try and she found this poem called A Musical Instrument, which she liked.

First a bit about the poet. Feminist criticism has focused attention upon the poetry of Elizabeth Browning, at the expense of her husband’s, Robert Browning, who nevertheless remains as one of the great poets in English.

Most of her poems are termed as bad (what about the perennial favourite, Sonnets from the Portuguese?), but in an occasional lyric like A Musical Instrument, Elizabeth Barrett catches fire.

An inexplicable malady kept her an invalid from 1838 to 46, when she and Robert Browning eloped to the continent, escaping whatever it was that animated her father's possessiveness. For two such difficult personalities, the Brownings got on reasonably well, in spite of Elizabeth Browning's right-wing politics – she adored Napoleon the Third. Her credulous belief in spiritualism was a provoking point for Robert Browning.

They had one son who settled down in Venice as an indifferent painter; the fame of both his parents must have been a burden for him. Browning died in Florence at the age of 55. Her husband's grief was enormous, but he survived her for 24 years, and never remarried, though he was surrounded by the admiring women of the Browning society.

What an interesting biography. More at https://poets.org/poet/elizabeth-barrett-browning

Devika chose this piece celebrating music. She always liked the character Pan – there was something cute about Pan, and she liked this poem instantly.

She then read the poem. It is lovely. It has a singing kind of quality about it, said Joe. Devika pointed out how charming is the description him makeing a pan flute out of the reeds.

‘Sweet, piercing sweet was the music of Pan's pipe’ reads the caption on this depiction of Pan by Walter Crane

Pan pipe

A pan pipe is a musical instrument composed of multiple pipes of varying lengths tied together, creating a wind instrument known as a pan flute or syrinx. The pipes, often made of bamboo or other materials, are arranged to produce different pitches when blown across the top. A prominent modern panpipe player is Gheorghe Zamfir, often called the “master of the pan flute.” You can hear him here:

There is a rich echoing melody within the pan pipe waiting to be unchained, which Elizabeth Barrett did in her poem.

Joe

Joe was drawn to the poems of Lawrence Ferlinghetti by a reading on May 26, Celebration Day, a day to remember and celebrate the lasting impact of those who have inspired and shaped our lives. He heard the British actor Helena Bonham Carter recite Ferlinghetti’s poem Don’t Let That Horse . . . .

It is about a painting by Marc Chagall, the Russian-French artist who painted and drew and made stained glass in the 1920s in France. In his painting Equestrienne, in 1931, a lady in a pink dress in the act of kissing, is held in the arms of her lover, astride a white horse. The horse is absurdly chewing a violin, and in the far corner a fiddler is playing a tune.

Equestrienne, 1931 by Marc Chagall

This scene is playing out in the mind of the poet as he writes the poem Don’t Let That Horse . . . :

Why was Bonham Carter reciting this poem on Celebration Day? She was remembering her beloved grandmother who also painted, and made imitation Chagalls in water colour in her whimsical way. Bonham Carter remarks, “… we're sort of a patchwork of every single person we've met, and every single person we've loved, and we still contain them. And even if people die, they remain part of our fabric, our internal world.”

Biography of Lawrence Ferlinghetti (1919–2021)

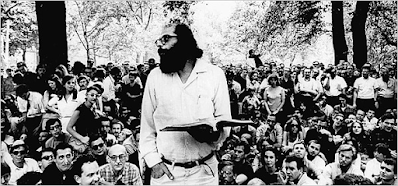

Lawrence Ferlinghetti was unusual. He was a pivotal American poet, publisher, and activist who played a central role in the San Francisco literary renaissance and the Beat movement. Born in Yonkers, New York, he endured a turbulent childhood, spending time in France, in an orphanage, and at a wealthy family’s home. After serving in the Navy, he earned degrees from Columbia University and the University of Paris before settling in San Francisco in the 1950s. There, he co-founded the City Lights Bookstore and its publishing arm, City Lights Publishers, which became a hub for avant-garde writers.

Ferlinghetti’s most famous work, A Coney Island of the Mind (1958), sold over a million copies, blending jazz rhythms, political dissent, and accessible language. He authored more than 30 poetry collections, including How to Paint Sunlight (2001) and Time of Useful Consciousness (2012), earning accolades like the National Book Critics Circle’s Lifetime Achievement Award. His poetry challenged elitism, embracing streetwise vernacular and social activism.

Allen Ginsberg reads Howl at Washington Square Park, New York (August 1966)

A defining moment in his career was publishing Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems (1956), which led to Ferlinghetti’s arrest on obscenity charges. The authorities cited as examples, the phrase

“who let themselves be fucked in the ad’s by saintly motorcyclists”

– this an explicit sexual reference the censors objected to.

The drug use references of which there are many is exemplified by

"who ate fire in paint hotels or drank turpentine in Paradise Alley, death, or purgatoried their torsos night after night"

– such descriptions of drug use were also thought objectionable in the conservative 50s.

Ferlinghetti’s victorious 1957 trial became a landmark free speech case, galvanising the Beat movement. He saw poetry as a democratic art form, calling his style ‘wide-open’ rather than strictly Beat; Pablo Neruda praised it for its expansiveness.

Beyond poetry, Ferlinghetti wrote experimental fiction, including Love in the Days of Rage (1988), set during Paris’s 1968 student uprising, and Little Boy (2019), a stream-of-consciousness memoir. He also created surrealist plays and visual art.

A lifelong advocate for artistic and political freedom, Ferlinghetti was named San Francisco’s first poet laureate in 1998 and received France’s Order of Arts and Letters. He died at 101, leaving a legacy as a cultural insurgent who bridged poetry and public life. As critic Larry Smith noted, his work “sings with the sad and comic music of the streets,” resonating with readers seeking truth in turbulent times.

(Condensed from https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/lawrence-ferlinghetti)

Ferlinghetti staggers his lines in an unorthodox fashion. He does not observe conventional prosody in regard to the rhythmic beats of poetry (like iambic, trochaic, etc), nor does he deal in rhymes – but which modernist poet does? He writes poetry as though he was conversing. He paints images with words associated with the thought. You can see action in phrases like:

horse

eat that violin

There is a jerkiness in the progress of the story and the beat, as though you are listening to jazz, not hearing words. He is often humorous, as in the ending:

there were no strings

attached

Joe recited one more, slightly longer poem by Ferlinghetti, The world is a beautiful place.

The world is a beautiful place, he says, but for a few inconveniences, which you have to get used to, and he gives examples:

…

if you don’t mind a touch of hell

…

if you don’t mind some people dying

all the time

…

if you don’t much mind

congressional investigations

and other constipations

that our fool flesh

is heir to

etc.

And when you are ‘living it up‘

right in the middle of it

comes the smiling

mortician

Ferlinghetti ends on the note of absurd death waiting to end all the beauty of the world.

You will be reminded of the dead minds among contemporary leaders so ready to launch their missiles and bombs in a hundred places now, as the USA goes to war with Iran on June 21, on behalf of Israel.

Oh the world is a beautiful place

to be born into

if you don’t much mind

a few dead minds

in the higher places

or a bomb or two

now and then

in your upturned faces

If you don't mind such improprieties as our name-brand society that we are prey to, with its men of distinction, and its men of extinction, and its priests, and other patrolmen, and its various segregations, and congressional investigations, and other constipations that our full flesh is heir to; yes, the world is the best place of all for a lot of such things as making the fun scene, and making the love scene, and making the sad scene, and singing low songs of having inspirations, and walking around, looking at everything, and smelling flowers, and goosing statues, and even drinking, and kissing people, and making babies, and wearing pants, and waving hats, and dancing, and going swimming in the rivers on picnics in the middle of the summer, and just generally living it up.

Yes, but then right in the middle of it comes the ‘shining mortician’, and that's the end of it.

It reminds us that the world is a ‘beautiful place.’ It’s a hilarious send up on the absurd world we live in. So true, someone said. There is a subtle sarcasm here which Saras noticed.

Realistic too since we are reading about the Gaza bombing every day in the papers, and on June 13 Israel initiated a gratuitous war of choice on Iran.

Priya

Priya chose the late Rebecca Ann Wood Elson, by profession a cosmologist, and by avocation a poet. She died very young; she was a Canadian, interested in astronomy, and astrophysics, and a poet also. Priya found this surprising. She came across her as poet on the Marginalian site (https://www.themarginalian.org/) maintained by Maria Popova, a Bulgarian essayist, author, and poet, who runs this very popular blog. She writes about poets, or authors; and self advertises her site as “most inspiring and nourishing reading in a single undistracted place, free, ad-free, algorithm-free, entirely human, made of feeling and time since 2006.”

Rebecca A. W. Elson, an astronomer whose work on dense star clusters significantly advanced our understanding of cluster dynamics and stellar evolution, died on May 19, 1999, from non-Hodgkins lymphoma at the age of 39

Rebecca Elson was born in 1960, and died in 1999 from a very rare kind of blood cancer. Her father was a geologist. She went with him on his field trips, and during her studies, she got interested in astronomy because she studied under famous astronomers. She matriculated in 1976, at the age of 16, after initially choosing biology, with a particular interest in genetics, then transferring to astronomy.

She earned a bachelor's degree from Smith College, where she was taught by a woman German astronomer, Waltraut Seitter. All through her studies, she worked under famous astronomers, and that's how she got interested in astronomy. She took a master's degree in physics from the University of British Columbia. Her special area was the study of Globular Clusters of stars, a spherical collection of stars that is bound together by gravity, with a higher concentration of stars towards its centre. It can contain anywhere from tens of thousands to many millions of member stars:

The Messier 80 globular cluster in the constellation Scorpius is located about 30,000 light-years from the Sun and contains hundreds of thousands of stars

Priya herself feels drawn towards space and the stars. Reading Elson’s poems, her interest was piqued. It is very sad that Elson passed away so young. She had managed to write a lot of poems, and written 56 scientific papers, and a slender book of poetry titled, A Responsibility to Awe. Her poems were published after her death by her husband, an Italian artist, Angelo Dicentio, and a friend and fellow poet, Anne Berkeley.

Rebecca Elson's A Responsibility to Awe was reissued as a Carcanet Classic

She headed the team to observe the Hubble Space Telescope images and provide a scientific analysis and interpretation. Later she wrote about it in popular science journals. All along, she had been writing poems, and Rebecca Elson's biography was published by the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography on 13th August 2020, as part of their collection of biographies of astronomers and mathematicians.

Priya chose two of her poems, Girl with the Balloon and Antidotes to Fear of Death.

Devika has a cousin who passed out of Smith, just five years her junior, and she will ask her whether she's heard about Elson.

Priya said it's very interesting to read Maria Popova's blog, because she comes up with very interesting poets. We are familiar with Maya Angelou's poem A Brave and Startling Truth which explores the potential for humanity to create a world of peace and understanding.

Rebecca Elson writes in the same vein, but she didn't become as famous a poet as she was an astronomer.

Girl with a Balloon ends on the lines:

A red balloon,

A little bit of pure Big Bang,

Bobbing at the end of her string

Mistakenly, Priya said how little do we realise when we carry a helium balloon, that we are carrying a little bit of the Big Bang with us. Priya liked the reference to the Big Bang. However, Helium (from helios, the sun, in Greek) was discovered neither in the Big Bang, nor on Earth, but in the Sun's spectrum by French astronomer Pierre Janssen and independently by English astronomer Joseph Norman Lockyer in 1868.

‘I eat the stars’ ... the Milky Way over Alberta, Canada. Photograph - Stocktrek Images, Inc

The second poem is Antidotes to Fear of Death. Elson died young and she knew that death was coming much earlier than it would for others. In her line of work she often lay horizontal looking through the eyepiece of telescopes. Thinking in that position she wrote

Sometimes as an antidote

To fear of death,

I eat the stars.

Those nights, lying on my back,

I suck them from the quenching dark

Til they are all, all inside me,

Pepper hot and sharp.

This poem made Priya feel we are all commingled in one space. We inherit a form, the human body, she said, but we are very much a part of this infinite universe, what might be called ‘spacelessness’ and ‘formlessness.’ Perhaps Elson understood that. Priya perceived a lot of depth in her writing. They are not just words but convey a lot of meaning within those words.

Priya was led to think of the American astronaut Sunita Williams being stuck there in space for eight to nine months, and how she lived and survived with her colleagues in the International Space Station (ISS).

Saras has mentioned a book called Orbital by Samantha Harvey. Priya is reading this fictional account of six astronauts in a space station, which she claims is a beautiful book. .There's something about the universe, the mystery, the unknown which draws our interest.

Saras said it's claustrophobic book also, and she doesn't like claustrophobia. When you look how they are inside that little capsule suspended somewhere in space, it makes you wonder why would anyone want to be shut up in that limited space, when you can enjoy the wide open spaces of Nature on Earth?

What happens on Earth including these bombings and the fighting and the killing make no sense to an astronaut up there.

Priya connected this poem of Elson to news of the Indian Air Force officer, Shukla, who is going to join the ISS soon. Good Luck! May he not have to drink recycled urine and sweat beyond the allotted mission time! Sunita Williams was originally scheduled for an 8-day mission to the ISS, but issues with the Boeing Starliner spacecraft, caused her stay to be extended to 286 days.

KumKum

KumKum asked one of the readers knowledgeable in French to pronounce the name of the poem she was going to read: Musée Des Beaux Arts. Joe volunteered the French pronunciation which is approximately “mu-ZAY day boh-zar.”

For her it would remain the Museum of Fine Arts. She narrated how she came across this poem when she was doing research in February to find her poet. Yes, she gets prepared months in advance, like Devika. She has even got her poem selected for the Romantic Poets session in August! Joe hoped she was not going to repeat any poem. Not at all, KumKum replied. Devika said the readers are obligated to check on Poets and Poems first. Quite often you like a poem and going there discover to your dismay it's already been done before. In point of fact KRG’s collection is quite an Anthology right there.

KumKum learned a new word when she was doing research for her poet: E-K-P-H-R-A-S-T-I-C. Joe told KumKum “You must teach Mr. Shashi Tharoor this one.” It's a word KumKum had never met before but would it tax ST? It means a poem or a piece of prose written about a painting, or an art object. Two examples, come to mind, first, Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn, which KumKum had done in 2018 in the Romantic Poets session, and was based on a visit Keats paid to the British Museum when he saw the Sosibios vase exhibited. She knew that Rilke was another ekphrastic poet, and found mention of Auden’s poem Musée Des Beaux Arts, and was led to the allpoetry.com website where she found its text, and thence to a very detailed article in the NYTimes with an illustration of Pieter Brueghel’s painting on which it is based:

Pieter Brueghel’s painting Landscape with The Fall of Icarus

Thus she decided to read this.

Auden visited the Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels in December 1938 and wrote the poem shortly afterward. Musée des Beaux Arts explores the theme of human indifference to suffering, particularly in relation to the famous painting Landscape with the Fall of Icarus by Pieter Brueghel the Elder. The poem not only describes this painting but also draws the reader’s attention to the Greek myth of Icarus.

W.H. Auden (1907-1973), poet and essayist - spending New Year's Eve with friends

Auden’s poem is a good example of an ekphrastic poem. Several paintings by various Old Masters (European painters active from the 13th to the 19th century) subtly enter into the poem. It also references the myth of Icarus, enriching the poem’s themes of suffering, neglect, and human routine.

Theme 1 – The Indifference of the World to Suffering

Auden observes that the Old Masters (like Brueghel) understood suffering happens while life goes on:

About suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window

or just walking dully along;

In Brueghel’s painting, Icarus’s legs flail in the water, yet the ploughman, shepherd, and ship sail by, oblivious. Auden notes the ship in the painting had "somewhere to get to" and sails past Icarus’s drowning.

Theme 2 – The Mundane vs. the Tragic

Auden contrasts extraordinary suffering (the fall of Icarus, Christ’s crucifixion) with ordinary life:

the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer's horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

Even martyrdom occurs in a "corner" while children skate on a pond.

Theme 3 – Art’s Role in Witnessing

Brueghel’s painting (and Auden’s poem) frame suffering as a peripheral event, forcing the viewer or reader to seek it out. The poem’s tone is detached, almost clinical—mirroring society’s apathy.

W. H. Auden was born on February 21, 1907, in Yorkshire, England, and died on September 29, 1973, in Vienna, Austria. His father was a medical doctor and his mother, a nurse. They were Catholic, and though Auden did not practice Catholicism as an adult; he remained a Christian nonetheless. He attended the University of Oxford for his graduate studies, where he excelled both intellectually and artistically. He became the leader of the “Auden Group,” a circle of politically and socially engaged poets. After graduating, his parents gifted him a gap year abroad, which he spent in Berlin, where he developed a deep affinity for the German language. Upon returning to England, he worked as a schoolmaster for five years. In 1939, he emigrated to America.

Auden wrote poetry throughout his life, and his work reflects both intellectual brilliance and technical mastery over various poetic forms. Although he never won a Nobel Prize, he received many other prestigious honours, including the Pulitzer Prize, the Bollingen Prize, the National Book Award, and the Professorship of Poetry at Oxford University (1956–1961). Auden is considered one of the major poets of the 20th century; after W. B. Yeats and T. S. Eliot, he was seen as the next great poetic voice.

Auden’s description of Brueghel’s painting is neither exhaustive nor always accurate – “try to find a horse scratching its ass on a tree in any of these,” as one critic wryly noted. But through humour and form, the poet skilfully mimics the tone and composition of paintings. The poem, composed shortly after his museum visit, reflects the impressions he gathered while viewing rooms full of works by the Old Masters. While Landscape with the Fall of Icarus is clearly a central influence, a close reading of the poem alongside the painting reveals echoes of other artworks as well.

The message of both the painting and the poem is deceptively simple: Suffering often goes unnoticed amid the ordinary flow of life. As one critic observes, “The poem is full of riches, hidden details that you might miss if, like a farmer with his head down – or a distracted museum-goer – you weren’t looking at the edges.” In the painting, fall of Icarus is barely noticeable, tucked into a corner where only his legs are visible sticking up from the green water.

As Elsa Gabbert writes in her New York Times article, A Poem and a Painting About Suffering That Hides in Plain Sight (March 6, 2022):

“The edges, as Auden keeps reminding us, are part of the picture. Ignoring them is the most natural thing in the world. It is also a moral error.”

Joe said his poem Don’t Let That Horse by Ferlinghetti also has to be seen, beside the Chagall painting of girl riding with a boy on a white horse holding a violin in its mouth. It too is therefore ekphrastic.

Devika took her leave at this point.

Pamela

Pamela spoke a little about Ted Hughes before reading the poem. The poem sounds similar on the surface to the one written by Tennyson (The Charge of the Light Brigade) because of the word ‘charge’ in the title Bayonet Charge. One is tempted to relate it to war again, but it's totally different. It has only peripherally to do with war, when you come to know Ted Hughes.

Short Bio of Ted Hughes

He was born Edward James Hughes on August 17, 1930 in West Yorkshire, England, and was a highly influential English poet and writer. He was raised in a working class family. Hughes developed a deep connection with nature and the countryside during his early years in Yorkshire.

He attended Mexborough Grammar School (estd. 1904) and later won a scholarship to Pembroke College, Cambridge. He studied English there and switched over later to archaeology and anthropology. He developed an interest in myth and folklore, which would play a significant role in his literary works.

Ted Hughes (1930—1998) photo by Reg Innell, Toronto Star

In 1956, Hughes married the American poet Sylvia Plath. The couple had a tumultuous relationship marked by intense creative collaboration, interspersed with personal struggles and conflicts. They had two children, Frieda (born 1960) and Nicholas (1962–2009). Nicholas was a wildlife scientist who died by suicide in his home in Fairbanks, Alaska. Frieda is now an English-Australian poet and painter. She has published seven children's books, four poetry collections and one short story and has had many exhibitions.

Tragically, in 1963, Sylvia Plath took her own life; she stuck her head in a gas oven, turned on the gas, and committed suicide as her children slept. This cast a long shadow over Hughes life and work. She died of carbon monoxide poisoning. Plath's death led to intense public scrutiny and controversy surrounding Hughes.

Hughes gained early recognition for his poetic talent. His debut collection, The Hawk and the Rain in 1957 received critical acclaim and established him as a promising poet. He followed it with Lupercal, which won the Hawthornden Prize.

Hughes continued to produce an impressive body of work. His poetry often grew from mythology, folklore and the natural world. He married Plath, and later he had an affair in 1963 with Assia Wevil. In July 1962 Plath discovered Hughes was having this affair; thereafter in September, Plath and Hughes separated. As a rebel, Wevil also committed suicide with the same gas stove six years later. It's so strange that he drove both his loves to commit suicide at the same gas stove, and he continued to live in the same house.

OMG, someone exclaimed. Yes it's strange, very strange.

In 1984, he was awarded the position of Poet Laureate, succeeding Sir John Benjamin. He kept this role until his death in 1998. He died of a heart attack while being treated for colon cancer. He died at the age of 68, very young.

Before reading the poem Pamela supplied the context of Bayonet Charge. It's not directly based on a specific war. The First World War took place in 1914, and the Second World War in 1939. Hughes was not born when the First World War took place, and he was only nine years old when the Second World War started. So he didn't have any direct experience of war. Ted Hughes himself was not personally involved in any major wars.

A bayonet charge

He is painting the scene of a war. It is a work of poetic imagination that captures the universal and timeless experiences of war. The poem doesn't explicitly reference a particular conflict, allowing its themes and emotions to resonate with a broader human experience of war and conflict.

He is known for writing other poems which relate to power and conflict. While the poem is not a direct autobiographical account, some have commented on the turbulent personal experiences of Hughes and Plath's marriage, as being a war.

Bayonet Charge was published in 1957, which was just one year into their marriage, and perhaps reflects the confusion, chaos, and conflict of their marriage. The conflict is related more to the marriage than to war, and their marriage lasted only for two years. Joe wondered metaphorically who fixed the bayonet and charged in their marriage.

Now to the poem. The poet is having the feelings of a person who might be going through a bayonet charge; all the things including this little animal play a part. Pamela liked the choice of the animal because a hare is so small and soft and harmless. It's symbolic of what war can do, even to such a creature,

rolled like a flame

And crawled in a threshing circle, its mouth wide

Open silent, its eyes standing out.

It really is heartrending to think how harmful war can be. His marriage was very turbulent. What kind of a man was he that he could drive two women to suicide!

Joe appealed for understanding. Sylvia Plath was mentally unwell long before. That has been noted. Even as a student in college she was suicidal. You can read at her wiki site “Plath made her first medically documented suicide attempt on August 24, 1953, by crawling under the front porch and taking her mother's sleeping pills.”

There were other factors, and Hughes was not blameless. To live with a person like Sylvia Plath, who had been undergoing psychiatric treatment would have been a challenge.

Joe said he doesn't know whether it is by way of atonement, but there is a very beautiful collection of poems called Birthday Letters that Hughes wrote over a period of time after Plath’s death. The poems are addressed to Plath chiefly, and were written over a period of more than twenty-five years, beginning a few years after her suicide in 1963. Some are love letters, others are haunted recollections and ruminations.

Joe came across the book in a bookstore once when he was traveling through Salt Lake City in Utah, and he read one or two poems and straight away bought it. He read a poem from the collection, Daffodils, in the Oct 2008 reading at KRG.

Hughes suffered, had himself caused suffering, and had been disloyal in his first marriage. All these things must have weighed on his mind.

People feel abandoned. It's very tough.

There are phrases in this poem that signify the hollowness of war:

King, honour, human dignity, etcetera

Dropped like luxuries in a yelling alarm.

It's very vivid. Another phrase that depicts the images related to war:

Then the shot-slashed furrows

Threw up a yellow hare that rolled like a flame

Another two lines with wrenching similes is this:

The patriotic tear that had brimmed in his eye

Sweating like molten iron from the centre of his chest, –

Saras

Louise Glück (1943- 2023) was an American poet and essayist. Considered by many to be one of America’s most talented contemporary poets, Glück was known for her poetry’s technical precision, sensitivity, and insight into loneliness, family relationships, divorce, and death. The poet Robert Hass called her “one of the purest and most accomplished lyric poets now writing.” In 2020, she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature “for her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal.”

Glück authored 13 books of poetry, including the collections Winter Recipes from the Collective (2021), The Wild Iris (1992), Faithful and Virtuous Night (2014), winner of the National Book Award, and Poems 1962–2012 (2013), which won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, as well as American Originality: Essays on Poetry (2017).

Glück’s poems invite readers to explore their deepest, most intimate feelings. Her ability to write poetry of the kind that many people can understand, relate to, and experience intensely and completely, stems from her deceptively straightforward language and poetic voice.

In a Washington Post Book World review of Glück’s The Triumph of Achilles, Wendy Lesser noted that “‘direct’ is the operative word here: Glück’s language is staunchly straightforward, and remarkably close to the diction of ordinary speech. Yet her careful selection for rhythm and repetition, and the specificity of even her idiomatically vague phrases, give her poems a weight that is far from colloquial.” Lesser went on to remark that “the strength of that voice derives in large part from its self-centeredness—literally, for the words in Glück’s poems seem to come directly from the center of herself.”

Louise Glück (rhymes with click) Born-1943, she won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2020 – the citation read 'for her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal'

In 2003, Glück was named the 12th US Poet Laureate. That same year, she was named the judge for the Yale Series of Younger Poets, a position she held until 2010. Her book of essays Proofs & Theories (HarperCollins, 1994) was awarded the PEN/Martha Albrand Award for Nonfiction.

In addition to the Pulitzer (1993) and Bollingen Prizes (2001), Glück received many awards and honours for her work, including the Lannan Literary Award for Poetry, a Sara Teasdale Memorial Prize, the MIT Anniversary Medal, the Wallace Stevens Award, a National Humanities Medal, and a Gold Medal for Poetry from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. She received fellowships from the Guggenheim and Rockefeller Foundations as well as the National Endowment for the Arts. She died in 2023.

Glück’s Pulitzer Prize-winning collection, The Wild Iris, clearly demonstrates her visionary poetics. Written in three segments, the book is set in a garden and imagines three voices: the gardener-poet, flowers speaking to the gardener-poet, and an omniscient god-like figure. In The New Republic, the critic and author Helen Vendler stated that “Glück’s language revived the possibilities of high assertion, assertion as from the Delphic tripod. The words of the assertions, though, were often humble, plain, usual; it was their hierarchic and unearthly tone that distinguished them. It was not a voice of social prophecy but of spiritual prophecy—a tone that not many women had the courage to claim.”

Saras chose to read two poems from The Wild Iris – both of them have ‘Vespers’ in their title. A Vesper is an evening prayer. The first one is Vespers [In your extended absence, you permit me]

In this poem a godmother is talking to God. Saras loved the blight that she's talking about on tomato plants. Often we go around our gardens looking for those little snails. There's always some heartbreak in the garden, something or the other. Saras could relate to this.

The second poem is Vespers ["Once I believed in you..."]

Saras loved this one too. Because the fig tree has died, it doesn't exist.

I planted a fig tree.

Here, in Vermont, country

of no summer. It was a test: if the tree lived,

it would mean you existed

Or you exist

exclusively in warmer climates,

in fervent Sicily and Mexico and California,

Saras thought that was funny.

But warmer climates have more pests and more of everything else, said Shoba another among our KRG gardeners.

Shoba

Shoba read the poet David Whyte. He's 69 years old and lives in Yorkshire. Whyte's mother was from Waterford, Ireland – known for its former glassmaking industry, and the Waterford Crystal factory, where decorative glass was manufactured. His father was a Yorkshire man. David Whyte has a degree in marine zoology from Bangor University, Wales. During his 20s, Whyte worked as a naturalist and lived in the Galapagos Islands, where he experienced a near drowning on the southern shore of Hood Island. He led anthropological and natural history expeditions in the Andes, the Amazon and the Himalayas. Whyte’s poetry is known for its eclectic and spiritual bent.

He attributes his poetic interest to the songs and the poetry of his mother's Irish heritage as well as to the landscape of West Yorkshire, where he grew up. He has commented that he had a Wordsworthian childhood in the fields and woods and on the moors. (Ted Hughes was born in Yorkshire. Charlotte Brontë, too)

David Whyte on the Big Sur in California

His collections of poetry include Songs for Coming Home (1984), Where Many Rivers Meet (1990), The House of Belonging (1996), River Flow: New & Selected Poems 1984–2007 (2006), and Pilgrim (2012). His works of prose frequently deal with his commitment to using poetry in business and organisational settings to encourage creativity, leadership, and engagement. His prose works include The Heart Aroused: Poetry and the Preservation of the Soul in Corporate America (1994), Crossing the Unknown Sea: Work as a Pilgrimage of Identity (2001), and The Three Marriages: Reimagining Work, Self and Relationship (2009).

Whyte is an associate fellow at Said Business School at the University of Oxford. He has worked with a variety of international companies and in 2008 was awarded an honorary doctorate from Neumann College, Pennsylvania. Whyte currently lives in the US Pacific Northwest.

Where Many Rivers Meet David Whyte, cover

The poem Shoba read is called Where Many Rivers Meet. Living in Kerala, where a water body is always close at hand and in Kochi where the river, backwaters and the sea merge; and experiencing the monsoon rains as “water from above “adds a magical dimension to the scene. This poem seemed apt for the monsoon season!

As the river merges into the sea, the mouth of the river sings of all its experiences, starting with the mountains and the lands it traverses. Each river adds to the sea; the sea remembers and sings back from its depths. A different song.. The creatures, and sea-weed and mountains and valleys of the salty ocean are unknown to the river. The poem explores the contrast between them.

Our experience of rivers in Kerala is different from Whyte’s imagination of a river. When you travel down Kerala, north or south, every few kilometres you're crossing a river because there are 44 rivers, crisscrossing this small state, flowing into the sea from the mountains in the East.

In Shoba’s childhood, most of the bridges fording these rivers were not built yet. To travel from her hometown to her grandmother's place, they had to stop the car and then, drive the car onto the jhankar or ferry. One really experiences the river, not speeding across a bridge, but actually being in the water, floating across on a pontoon. The rivers were so clear then.

When they reached their grandmother's house, the children would jump into the river. Her brothers would swim and they would splash around in the river. That was the experience, in our kayal, the backwaters. We are actually surrounded by water.

That is so different from how Whyte imagines it in his homeland and he writes about it. His imagination and Shoba’s imagination, the feelings about water and all that surrounds us is very different.

Whyte says that the river sings of the mountains. The river is flowing through land and is intimately connected to the earth, and sings of the mountain where it starts.

When travellers go to Munnar hill station they see a tiny trickle of a waterfall on the way where the river actually begins in the mountains. As we come down, that trickle becomes a little bigger. And then we will see the river starting to flow rapidly.

Shoba was reminded of these lines from the song A Horse with No Name by the writer Dewey Bunnell who says the song is ”a metaphor for a vehicle to get away from life's confusion into a quiet, peaceful place.”

The ocean is a desert with its life underground

And a perfect disguise above…

The present poem delves into the cyclic nature of water on our planet. The vast expanse of sea .. the sun turning the water to vapour which forms clouds, the winds that carry these clouds to the land, the mountains that cause rain to fall and form rivers that flow into the sea.

All that experience that we have of the rivers, it is very special in Kerala and different from Whyte’s imagination. Yet Shoba liked the short poem he wrote.

I float on cloud become water,

central sea surrounded by white mountains,

the water salt, once fresh,

cloud fall and stream rush, tree root and tide bank

leading to the rivers' mouths

The last part is haunting:

and sings back

from the depths

where nothing is forgotten.

We do see the mouth of the river Periyar at Cherai beach where it empties into the Arabian Sea.

Shoba’s comparison and contrast with Kerala rivers was delightful.

One does not realise there are so many rivers flowing in Kerala. Whichever direction you drive, south or north, you will cross these rivers. Ultimately, it's because we have this range of mountains to the East, the Nilgiris, for when the clouds hit the Nilgiris they drop their load of water as rain and it trickles down. It’s the monsoon that starts it off. Kerala always has water. But in North India, when you travel train, say, you often see dry river beds, which are never seen in Kerala. The Yamuna River in Delhi is mostly dry, the river really only flows when there are rains during the monsoon. Only a few months of the year, do you see the Yamuna flowing in Delhi.

The Ganga however is never dry, but so many small rivers are dry most of the time. The river near Shantiniketan, the Kopal (or Sal) is so dry that KumKum and Joe were walking on the riverbed when they visited Shantiniketan. They cultivate right in the river bed, and what grows very well there are melons. You plant and the fruit comes quickly. It’s all that rich silt covering the riverbed.

Zakia

Zakia read from Spike Milligan's poems which were previously read by Gopa during one of our Humorous Poets sessions.

Spike Milligan doesn't need much of an introduction, since we’ve done him before. His name was Terence Allen Milligan. He was an Irish comedian, writer, musician, poet, playwright, and actor, the son of an English mother and Irish father. He was born in India on April 16, 1918, and spent his childhood in Pune and later in Rangoon.

He disliked his name and began to call himself Spike after hearing the band Spike Jones and the City Slickers on Radio Luxembourg. He was also the co-creator of the British radio comedy, The Goon Show with Peter Sellers. Here’s a short video of Spike Milligan telling his war stories

He wrote comical verse, much of it for children. One of his poems, we've done before (by Gopa) called On the Ning, Nang, Nong. We read that in 2018. It was voted the UK's favourite comic poem.

Once when Spike Milligan appeared in Scottish kilt and tartan, he was asked “Is anything worn under the kilt?” He replied, “No, it’s all in perfect working order.”

And then we've also read his novel Puckoon in May 2019 (‘Pops with the erratic brilliance of a careless match in a box of firecrackers’).

Spike Milligan (1918–2002)

He had a bipolar disorder for most of his life and many mental breakdowns.

Zakia read two of his poems, Bazonka and Unto Us...

Bazonka is a funny poem; it's got some nonsensical stuff, but it highlights the power of repetition and the absurdity of superstition.

Say Bazonka every day

That's what my grandma used to say

It keeps at bay the Asian Flu'

He refers to the Asian flu of 1957-58, much after World War II. He talks about Tiny Tim, the performer.

Zakia was reminded of Covid-19, and how we were told to beat the virus with various measures like washing our hands, cleaning the vegetables, lighting a candle, etc. That was a little bit superstitious, and told of humanity flailing about in ignorance.

The second poem is Unto Us....

When Zakia read this poem and came to the part of the brass plate in Wimpole Street, she realised this poem was about an abortion and the foetus. Milligan was trying to compare an abortion to a murder.

This little foetus cries out –

I was!

Small, but I WAS!

Tiny, in shape

Lusting to live

I hung in my pulsing cave.

But then because there was no Queen's counsel to take its brief, its passing was not even mourned.

It was celebrated because of the parents.

The father just bought tickets to a movie

My death was celebrated

With tickets to see Danny la Rue

And there was nothing more to it than going to see an entertainer, known for theatrical productions and television shows.

This poem appealed to Zakia for this stark message.

Joe said

There was no Queens Counsel

To take my brief.

refers to the fact that abortion was illegal in British law at the time, but the foetus would have needed a lawyer to actually prosecute his parents.

He's imagining himself not being born. I guess we're all lucky to have been born because of some happy accident of concupiscence and conjoining long long ago.

In the first few lines, he's optimistic and he promises to give love. But then when it comes to the doctor's clinic, he is resigned to the fact that he won’t exist, and the cot that he might have warmed will remain in Harrod’s.

Unto Us is a biblical phrase which harks back to Isaiah 9:6 which prophesies the birth of Jesus. In the King James Version of the Bible, we read:

For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given: and the government shall be upon his shoulder: and his name shall be called Wonderful, Counsellor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace.

Milligan cites only a part of it in the title because the whole quotation would have been well known to his audience.

Now we will write a poem Unto Us for Devika who has been reborn and has come back into our midst after a long stay in the hospital ! Here it is from Joe:

Golden as Sauterne

The day we learned she’d taken ill

We all came down in gloom,

Her plumbing had come to a standstill

– Her digestion had no room.

Lakeshore is no playground

To frolic and go skating,

But you can make a turnaround

If Ramesh is operating !

Unto us she’s made a return,

And happy are we to see

She’s as perky as can be –

As golden as a sauterne !

The surgeon referred to is the famous Dr. H. Ramesh, Senior Consultant, and Director of Surgical Gastroenterology at VPS Lakeshore Hospital.

The Poems

Arundhaty 2 poems by WB Yeats

1. The Lake Isle of Innisfree

I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made;

Nine bean-rows will I have there, a hive for the honey-bee,

And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow,

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings;

There midnight’s all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet’s wings.

I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart’s core.

2. Aedh Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven

Had I the heavens’ embroidered cloths,

Enwrought with golden and silver light,

The blue and the dim and the dark cloths

Of night and light and the half light,

I would spread the cloths under your feet:

But I, being poor, have only my dreams;

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

Devika

A Musical Instrument by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

I.

WHAT was he doing, the great god Pan,

Down in the reeds by the river ?

Spreading ruin and scattering ban,

Splashing and paddling with hoofs of a goat,

And breaking the golden lilies afloat

With the dragon-fly on the river.

II.

He tore out a reed, the great god Pan,

From the deep cool bed of the river :

The limpid water turbidly ran,

And the broken lilies a-dying lay,

And the dragon-fly had fled away,

Ere he brought it out of the river.

III.

High on the shore sate the great god Pan,

While turbidly flowed the river ;

And hacked and hewed as a great god can,

With his hard bleak steel at the patient reed,

Till there was not a sign of a leaf indeed

To prove it fresh from the river.

IV.

He cut it short, did the great god Pan,

(How tall it stood in the river !)

Then drew the pith, like the heart of a man,

Steadily from the outside ring,

And notched the poor dry empty thing

In holes, as he sate by the river.

V.

This is the way,' laughed the great god Pan,

Laughed while he sate by the river,)

The only way, since gods began

To make sweet music, they could succeed.'

Then, dropping his mouth to a hole in the reed,

He blew in power by the river.

VI.

Sweet, sweet, sweet, O Pan !

Piercing sweet by the river !

Blinding sweet, O great god Pan !

The sun on the hill forgot to die,

And the lilies revived, and the dragon-fly

Came back to dream on the river.

VII.

Yet half a beast is the great god Pan,

To laugh as he sits by the river,

Making a poet out of a man :

The true gods sigh for the cost and pain, —

For the reed which grows nevermore again

As a reed with the reeds in the river.

Joe 2 Poems by Lawrence Ferlinghetti

1. Don’t Let That Horse . . .

Don’t let that horse

eat that violin

cried Chagall’s mother

But he

kept right on

painting

And became famous

And kept on painting

The Horse With Violin In Mouth

And when he finally finished it

he jumped up upon the horse

and rode away

waving the violin

And then with a low bow gave it

to the first naked nude he ran across

And there were no strings

attached

2. The world is a beautiful place

The world is a beautiful place

to be born into

if you don’t mind happiness

not always being

so very much fun

if you don’t mind a touch of hell

now and then

just when everything is fine

because even in heaven

they don’t sing

all the time

The world is a beautiful place

to be born into

if you don’t mind some people dying

all the time

or maybe only starving

some of the time

which isn’t half so bad

if it isn’t you

Oh the world is a beautiful place

to be born into

if you don’t much mind

a few dead minds

in the higher places

or a bomb or two

now and then

in your upturned faces

or such other improprieties

as our Name Brand society

is prey to

with its men of distinction

and its men of extinction

and its priests

and other patrolmen

and its various segregations

and congressional investigations

and other constipations

that our fool flesh

is heir to

Yes the world is the best place of all

for a lot of such things as

making the fun scene

and making the love scene

and making the sad scene

and singing low songs of having

inspirations

and walking around

looking at everything

and smelling flowers

and goosing statues

and even thinking

and kissing people and

making babies and wearing pants

and waving hats and

dancing

and going swimming in rivers

on picnics

in the middle of the summer

and just generally

‘living it up’

Yes

but then right in the middle of it

comes the smiling

mortician

KumKum

Musée Des Beaux Arts by W.H. Auden

About suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer's horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Brueghel's Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

Pamela

Bayonet Charge by Ted Hughes

Suddenly he awoke and was running – raw

In raw-seamed hot khaki, his sweat heavy,

Stumbling across a field of clods towards a green hedge

That dazzled with rifle fire, hearing

Bullets smacking the belly out of the air –

He lugged a rifle numb as a smashed arm;

The patriotic tear that had brimmed in his eye

Sweating like molten iron from the centre of his chest, –

In bewilderment then he almost stopped –

In what cold clockwork of the stars and the nations

Was he the hand pointing that second? He was running

Like a man who has jumped up in the dark and runs

Listening between his footfalls for the reason

Of his still running, and his foot hung like

Statuary in mid-stride. Then the shot-slashed furrows

Threw up a yellow hare that rolled like a flame

And crawled in a threshing circle, its mouth wide

Open silent, its eyes standing out.

He plunged past with his bayonet toward the green hedge,

King, honour, human dignity, etcetera

Dropped like luxuries in a yelling alarm

To get out of that blue crackling air

His terror’s touchy dynamite.

Priya 2 Poems by Rebecca Elson

1. Girl with a Balloon

From this, the universe

In its industrial age,

With all the stars lit up

Roaring, banging, spitting,

Their black ash settling

Into every form of life,

You might look back with longing

To the weightlessness, the elemental,

Of the early years.

As leaning out the window

You might see a child

Going down the road,

A red balloon,

A little bit of pure Big Bang,

Bobbing at the end of her string

2. Antidotes to Fear of Death

Sometimes as an antidote

To fear of death,

I eat the stars.

Those nights, lying on my back,

I suck them from the quenching dark

Til they are all, all inside me,

Pepper hot and sharp.

Sometimes, instead, I stir myself

Into a universe still young,

Still warm as blood:

No outer space, just space,

The light of all the not yet stars

Drifting like a bright mist,

And all of us, and everything

Already there

But unconstrained by form.

And sometime it’s enough

To lie down here on earth

Beside our long ancestral bones:

To walk across the cobble fields

Of our discarded skulls,

Each like a treasure, like a chrysalis,

Thinking: whatever left these husks

Flew off on bright wings.

Saras 2 poems by Louise Glück

1. Vespers [In your extended absence, you permit me]

In your extended absence, you permit me

use of earth, anticipating

some return on investment. I must report

failure in my assignment, principally

regarding the tomato plants.

I think I should not be encouraged to grow

tomatoes. Or, if I am, you should withhold

the heavy rains, the cold nights that come

so often here, while other regions get

twelve weeks of summer. All this

belongs to you: on the other hand,

I planted the seeds, I watched the first shoots

like wings tearing the soil, and it was my heart

broken by the blight, the black spot so quickly

multiplying in the rows. I doubt

you have a heart, in our understanding of

that term. You who do not discriminate

between the dead and the living, who are, in consequence,

immune to foreshadowing, you may not know

how much terror we bear, the spotted leaf,

the red leaves of the maple falling

even in August, in early darkness: I am responsible

for these vines.

2. Vespers ["Once I believed in you..."]

Once I believed in you; I planted a fig tree.

Here, in Vermont, country

of no summer. It was a test: if the tree lived,

it would mean you existed.

By this logic, you do not exist. Or you exist

exclusively in warmer climates,

in fervent Sicily and Mexico and California,

where are grown the unimaginable

apricot and fragile peach. Perhaps

they see your face in Sicily; here we barely see

the hem of your garment. I have to discipline myself

to share with John and Noah the tomato crop.

If there is justice in some other world, those

like myself, whom nature forces

into lives of abstinence, should get

the lion's share of all things, all

objects of hunger, greed being

praise of you. And no one praises

more intensely than I, with more

painfully checked desire, or more deserves

to sit at your right hand, if it exists, partaking

of the perishable, the immortal fig,

which does not travel.

Shoba

Where Many Rivers Meet, poem by David Whyte 2004

All the water below me came from above

All the clouds living in the mountains

gave it to the rivers

who gave it to the sea, which was their dying.

And so I float on cloud become water,

central sea surrounded by white mountains,

the water salt, once fresh,

cloud fall and stream rush, tree root and tide bank

leading to the rivers' mouths

and the mouths of the rivers sing into the sea,

the stories buried in the mountains

give out into the sea

and the sea remembers

and sings back

from the depths

where nothing is forgotten.

Zakia 2 poems by Spike Milligan

1. Bazonka

Say Bazonka every day

That's what my grandma used to say

It keeps at bay the Asian Flu'

And both your elbows free from glue.

So say Bazonka every day

(That's what my grandma used to say)

Don't say it if your socks are dry!

Or when the sun is in your eye!

Never say it in the dark

(The word you see emits a spark)

Only say it in the day

(That's what my grandma used to say)

Young Tiny Tim took her advice

He said it once, he said it twice

he said it till the day he died

And even after that he tried

To say Bazonka! every day

Just like my grandma used to say.

Now folks around declare it's true

That every night at half past two

If you'll stand upon your head

And shout Bazonka! from your bed

You'll hear the word as clear as day

Just like my grandma used to say!

2. Unto Us...

Somewhere at some time

They committed themselves to me

And so, I was!

Small, but I WAS!

Tiny, in shape

Lusting to live

I hung in my pulsing cave.

Soon they knew of me

My mother —my father.

I had no say in my being

I lived on trust

And love

Tho' I couldn't think

Each part of me was saying

A silent 'Wait for me

I will bring you love!'

I was taken

Blind, naked, defenceless

By the hand of one

Whose good name

Was graven on a brass plate

in Wimpole Street,

and dropped on the sterile floor

of a foot operated plastic waste

bucket.

There was no Queens Counsel

To take my brief.

The cot I might have warmed

Stood in Harrod's shop window.

When my passing was told

My father smiled.

No grief filled my empty space.

My death was celebrated

With tickets to see Danny la Rue

Who was pretending to be a woman

Like my mother was.

,%20poet%20and%20essayist%20-%20The%20only%20way%20to%20spend%20New%20Year's%20Eve%20is%20either%20quietly%20with%20friends%20or%20in%20a%20brothel.jpg)

,%20poet%20%E2%80%93%20Photo%20by%20Reg%20Innell-Toronto%20Star%20via%20Getty%20Images.png)

%20The%20Nobel%20Prize%20in%20Literature%202020%20Born-%201943,%20New%20York,%20NY,%20USA%20Prize%20citation%20-%20'for%20her%20unmistakable%20poetic%20voice%20that%20with%20austere%20beauty%20makes%20individual%20existence%20universal'.png)

%20on%20the%20BIg%20Sur%20in%20California.png)

Very well done,Joe!

ReplyDeleteAll for the return of Devika 🌺Beautifully put together Joe, very nice

ReplyDeleteWonderful blog Joe .. I loved listening to the pan flute .. so interesting all the additions to our reading the pictures and all. This one was a great welcome for dear Devika.

ReplyDeleteWhile going through the poems submitted I look for things on the web that will illustrate the poems and anything the poets might refer to, and download the links, images, etc that will flesh out the blog and collect them in a folder for that Session.

DeleteAbsolutely superb blog Joe . Thank you and all the others who contributed to this blog . I think you have certainly excelled yourselves . I am proud to be a part of this . I too hope to give more to this effort in the future . Devika who is always the first to contribute need special appreciation for making the effort to be present so soon after the serious surgery. You deserve a 🏅

ReplyDeleteGood you liked it - thanks for commenting

DeleteI too am proud to be a part of KRG,

ReplyDeleteA group of wonderful individuals

Enjoyed going through the blog. Good fun! Thanks Joe.

ReplyDeleteI savoured this blog! There was so much to think about. The paintings added to the enjoyment of the two poems on which they were based.Excellent poems, all.

ReplyDeleteThank you Joe. So happy to be part of KRG.

Very happy you enjoyed it, dear Shoba.

DeleteThe marvellous thing is the post will remain there as a record of enjoyment which you can return to years later. It takes on an added piquancy when death has taken away a reader, but hiser words endure in this record.

Yes!! These poems we have selected also enjoy a new life in these blogs.

DeleteYes! This month’s blog had much information. Delightful reading. I was mad with Joe yesterday, but his beautiful blog post made me opt for a “Ceasefire”, unconditionally.

ReplyDelete